1. Concurrent Product Development

Concurrent product development first appeared in the late 1980s as an upgrade of the traditional sequential product development. It is defined as “… a systematic approach to the integrated, concurrent design of products and their related processes, including manufacturing and support. This approach is intended to cause the developers from the very outset to consider all elements of the product life cycle, from conception to disposal, including quality, cost, schedule, and user requirements”

[1].

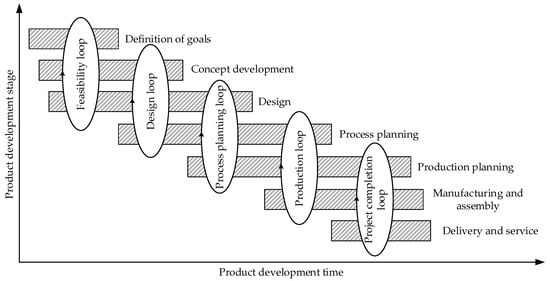

In concurrent product development, the traditionally sequential development stages overlap. For performing the interactions between the overlapping stages, the track-and-loop approach has been proposed. In the track-and-loop approach, the overlapping stages are combined into development loops; this facilitates communication and enables constant information sharing. For SMEs, Winner et al. propose the adoption of 3-T loops, which means that three consecutive stages overlap and interact

[1]. The general concurrent product development process with the application of 3-T loops is shown in

Figure 1 [2].

Figure 1. General concurrent product development process with the application of 3-T loops

[2].

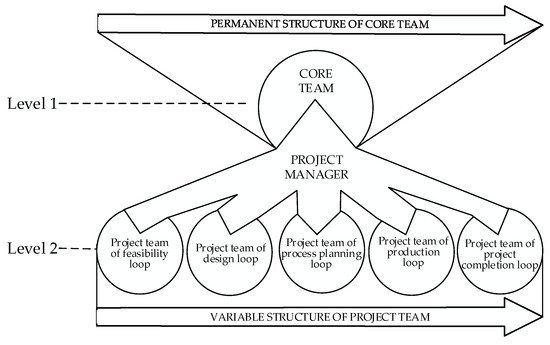

For efficient execution of development loops, good multidisciplinary teamwork is a must. According to Duhovnik et al., SMEs should adopt a two-level team structure: the core team and the project team

[3]. The core team consists of the core team leader, representatives of individual functional departments, and project manager. Its composition is permanent and does not change during the project. The project team is responsible for carrying out project activities. The project manager represents a standing member of the project team, while other team members change depending on the development loop underway. With this structure, it is ensured that at each moment, the right experts from different functional departments are working on the project. Constant collaboration and information sharing between team members with different expertise allow for a better understanding of the problem and timely detection of potential discrepancies. The two-level team structure in SMEs is shown in

Figure 2 [3].

Figure 2. Two-level team structure in SMEs

[3].

The main goal of concurrent product development is achieving higher project efficiency, as customers are primarily interested in the price, quality, and functionality of the product

[4]. Studies have shown that applying concurrent product development strategies (parallelism, standardization, and integration

[5]), track-and-loop approach, and appropriate concurrent engineering tools (e.g., design for manufacturability (DFM), design for assembly (DFA), quality function deployment (QFD), failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA), etc.

[6]) can lead to up to 60% shorter development times, up to 50% lower costs, and as much as 95% fewer errors and necessary changes

[7]. Another important factor in achieving greater project efficiency is also detailed upfront planning. While in the traditional sequential product development, on average 3% of total order development time is used for planning, in concurrent product development this time increases to about 20%

[8]. This enables detection and elimination of discrepancies early on when the implementation of potential changes is easier and less expensive

[9].

Although concurrent product development, based on detailed upfront planning, enables greater project efficiency in rather stable project environments, it does not offer the necessary means to address the challenges of today’s turbulent environment. Companies are becoming more and more aware that they need to upgrade their standard development approach with appropriate principles that will introduce greater flexibility and enable a more rapid and effective response to change.

2. Agile Project Management

APM approach first emerged in the software industry as an alternative to traditional deterministic approaches that no longer allowed for effective development in highly unpredictable and competitive environments

[10]. It became widely popular with the release of the Agile Manifesto in 2001, where 17 prominent practitioners presented better ways of developing software. Through their work, they have come to value (1) individuals and interactions over processes and tools; (2) working software over comprehensive documentation; (3) customer collaboration over contract negotiation; (4) responding to change over following a plan

[11]. The main goal of APM is to ensure greater flexibility and faster response to change by reducing documentation and minimizing upfront planning

[12]. The main differences between traditional and agile project management approaches are presented in

Table 1.

Table 1. The main differences between traditional and agile project management approaches.

| Characteristic |

Traditional Project Management Approach |

Agile Project Management Approach |

| Environment |

Stable, predictable |

Turbulent, dynamic, unpredictable |

| Project size |

Large projects |

Small projects |

| Requirements and specifications |

Known upfront, big changes not expected |

Rough initial definition, gradual development, in a form of user stories, changes encouraged |

| Planning |

Detailed upfront planning for the whole project |

Iterative and adaptive planning, detailed planning for one iteration upfront only |

| Development approach |

Sequential development stages, strictly following an initial project plan |

Short iterations, iterative and incremental development |

| Teamwork |

Larger teams, high level of specialization, hierarchy levels, responsibilities clearly assigned |

Smaller teams, generalizing specialists, self-organization, full dedication, colocation, daily meetings |

| Management style |

Control and command |

Leading and cooperating |

| Customer collaboration |

Initial involvement (project definition) |

Active involvement in product development, frequent feedback information |

| Communication |

Formal |

Informal |

| Quality control |

Process-oriented, detailed planning, strict control, testing later on |

People-oriented, constant control of requirements and solutions, frequent testing |

| Goals |

Optimization, predictability |

Adaptability, flexibility, responsiveness, quick value delivery |

| Project success |

Project triangle (time, costs, quality) |

Project triangle (time, costs, quality), stakeholder satisfaction |

Definitions of APM still differ, however, in general, it can be defined as “… an approach that seeks flexibility, simplicity, iterations in short period of time, and incrementally add value”

[13]. In APM, the whole development process is partitioned into short iterations, and after each iteration, a working, potentially marketable partial product is delivered to the customer. The customer, who is actively involved in the development process, tests the product increments and constantly provides feedback information. This allows for faster identification of discrepancies, rapid response to change, and development of the product that the customer wants and needs.

For achieving greater project agility, many practices have proven to be very beneficial and are nowadays frequently used for managing complex software projects. Some of the most popular APM practices are listed and briefly described in Table 2.

Table 2. Popular APM practices.

| APM Practice |

Description |

| Iterative development |

The whole development process is partitioned into short iterations (1–4 weeks long). |

| Iterative planning |

Instead of upfront planning, a plan is developed iteratively for one iteration upfront only. |

| Incremental development, frequent value delivery |

Each iteration results in a working product increment customers can already use. |

| Time boxing |

The duration of activities (meetings, iterations) is defined upfront and is fixed. |

| Active customer collaboration |

The customer is involved in the development throughout the project and constantly provides feedback and collaborates with the project team. |

| Product backlog |

The project is cut into small pieces that are prioritized based on customers’ business needs. Project backlog is flexible and updated frequently. |

| User stories |

Customer requirements and needs are provided in terms of short and simple descriptions of desired functionalities. |

| Small self-organized interdisciplinary teams |

Teams are small (usually 7 ± 2 members), all team members are equal (no team leader), tasks are internally rearranged between team members, each team member can take on each task |

| Colocation |

All team members are located in the same room. |

| Daily standup meetings |

Short standup meetings (15 min) are carried out every day at the same time and in the same location where project progress is discussed. |

| Test-driven development |

Before fully developing software, test cases are prepared to test new code. |

| Pair programming |

Team members work in pairs, one writes the code while the other supervises. Roles are frequently switched. |

| Burndown chart |

For greater transparency, work left to do versus time is graphically represented. |

| Simplicity |

Designing simple software is cheaper and quicker, and it allows for easier problem fixing. |

| Continuous integration |

All new code is first verified and then connected with the existing code. |

| Retrospectives |

Retrospectives should be carried out frequently to analyze good and bad practices and identify possibilities of improving processes. |

Based on the APM best practices, many different structured agile methods have been developed over the years. All of the existing methods are based on iterative and incremental development, collaboration, simplicity, and adaptability

[14] but differ in their depth of guidance and breadth of their life cycles

[15]. Among the most popular APM methods are scrum, kanban, scrumban, extreme programming (XP), feature-driven development (FDD), dynamic system development method (DSDM), crystal methods, etc.

[15][16][17].

The benefits of APM methods, which are nowadays considered to be the mainstream in software development

[10], are numerous: more effective and rapid response to change, timely identification of errors, greater flexibility, improvements in teamwork, greater transparency, etc.

[18][19]. Consequently, APM has started to gain recognition also outside the software industry. Due to some discipline-specific differences, a direct transfer of APM methods to other industry sectors is not possible

[20], but the so-called hybrid models have started to emerge that can represent a good alternative for non-software companies

[21].

3. Hybrid Models

Hybrid models combine agile methods with traditional product development models

[22][23], thus enabling companies to take advantage of agility without sacrificing the stability provided by traditional approaches

[22][24]. Many researchers agree that it is the balance between agile and traditional approaches that is usually the most effective for managing projects

[12][25][26][27]. A study by Gemino et al. showed that hybrid approaches lead to higher stakeholder satisfaction than traditional approaches while allowing for a comparable project efficiency as completely agile approaches

[26].

Of all the existing agile methods, scrum has the greatest potential for physical product development

[28][29]. The reason for this can be found in the fact that scrum is relatively simple, direct, and well documented, compared with other agile methods. Additionally, Sommer et al. (2015) state that scrum is the only agile method that directly addresses all aspects of project management and is explicitly intended for managing projects across the development process

[30]. Most often, scrum is combined with the traditional stage-gate model, which is still very frequently used in product development

[31][32].

Cooper, the father of the stage-gate model, addressed a number of criticisms of this traditional model in his 2014 article

[32], such as strict linearity, rigidity, inflexibility, and a high level of bureaucracy. He discussed the next generation of the stage-gate model, which needs to become more flexible, agile, and accelerated in order to be able to effectively manage innovative and dynamic projects. He also introduced the idea of a protocept, equivalent to a working product increment in agile software development. A protocept can represent anything from the initial concept to the final working prototype, something that leads us closer to the final product and enables customers to provide feedback information on

[32].

Based on Cooper’s work, Sommer et al. later developed the agile–stage-gate hybrid, proposing the use of a stage-gate model on the strategic management level and scrum on the operational level

[30]. The hybrid is based on the adaptation of typical scrum events (sprint planning, sprint review, sprint retrospective, daily scrum), scrum roles (scrum master, product owner, development team), and scrum artifacts (product backlog, sprint backlog, sprint increment, i.e., protocept). Case studies in various multinational corporations (Lego Group, Danfoss, Tetrapak, etc.) have shown that the implementation of the proposed hybrid leads to significant improvements, such as design flexibility, faster response to change, improved productivity, better communication, improved productivity, and raised team morale

[28][33][34][35]. There have also been some attempts to implement the proposed agile–stage-gate hybrid in SMEs. The study of Edwards et al. has shown that the implementation is possible; however, it requires some additional adaptations and leads to less evident improvements

[36].

Conforto and Amaral developed the IVPM2 method for managing innovative product development projects. The method combines the traditional stage-gate model approach (phase definition, standardized documentation, and checkpoints) with different scrum elements (iterative cycles, visual boards, and daily standup meetings)

[27]. Research has shown that simple iterative and visual agile practices, combined with good practices of traditional product development, lead to greater creativity and innovation, greater added value for the customer, shorter planning time, and improved communication between all stakeholders

[27][37].

Schuh et al. designed a customized scrum model for a highly iterative innovation process and rapid realization of physical product ideas

[38]. The model is based on continuous integration of customers and production engineers and early and stepwise development of prototypes. As key enablers, integrated ICTs, interdisciplinary teams, a product lifecycle management system, and scalable manufacturing technologies are suggested. The authors also highlight the potential advantages of running individual cycles in parallel, which could further accelerate development

[38].

Ullman presented an adapted scrum framework for hardware design and proposed its use in the combination with the stage-gate model

[29]. In his book, he presented thirteen steps of the proposed framework that are being executed within the

organize–plan–do–review cycle. Similar to the agile–stage-gate hybrid

[30], Ullman’s adapted scrum framework also preserves the typical scrum events, roles, and artifacts

[29].

Reichwein et al. recognized APM as a potential solution to the problems of the additive manufacturing industry. They designed additive manufacturing adapted scrum procedure that stresses the importance of frequent production of prototypes, which allows for early testing of product functionality and facilitates the introduction of changed or new requirements

[39].

As a first attempt to combine scrum with a concurrent product development model, Žužek et al. presented a conceptual agile–concurrent hybrid

[40]. They propose that concurrent product development framework remains unchanged (stages overlap, the track-and-loop approach is preserved, etc.), while scrum is proposed for the execution of day-to-day work. As the main advantage of the proposed hybrid, the authors stress a more comprehensive protocept that in agile–concurrent hybrid represents the result of an entire development loop, not only of one stage. This allows for a broader insight into the project progress and more extensive customer feedback.

Combining APM and concurrent product development elements has also been recognized as a promising solution for advanced mass customization and one-of-a-kind production

[41]. The study of Varl et al. showed that such a combination can result in great direct savings (reduced time to market, rework, man-hours, etc.) and indirect savings (improved knowledge management, improved information flow, etc.). They have also reported increased team motivation, a lower number of changes during later phases, and enhanced effectiveness.

The results of hybrid models applied to physical product development in large organizations are very promising; however, there is a great lack of literature regarding agile and hybrid approaches in SMEs

[36]. This is rather surprising, concerning SMEs account for the majority of businesses worldwide. The few existing studies indicate that the implementation of APM in SMEs is feasible but much more challenging than in larger enterprises

[36][42]. Both Edwards et al.

[36] and Žužek et al.

[42] showed that ensuring fully dedicated team members, which represents an important element of APM, is almost impossible in SMEs. Additionally, the implementation of existing hybrids requires a complete company reorganization, which usually calls for employing agile experts

[35][43]. Most SMEs usually do not have enough financial and non-financial resources to afford such an extensive transformation and therefore need an alternative approach that will still allow them to increase their agility but without such high inputs and risks related to it.