The CHYR (CHY ZINC-FINGER AND RING FINGER PROTEIN) proteins have been functionally characterized in iron regulation and stress response in Arabidopsis, rice and Populus. In soybean, 16 CHYR genes with conserved Zinc_ribbon, CHY zinc finger and Ring finger domains were obtained and divided into three groups. Moreover, additional 2–3 hemerythrin domains could be found in the N terminus of Group III. Phylogenetic and homology analysis of CHYRs in green plants indicated that three groups might originate from different ancestors. Expectedly, GmCHYR genes shared similar conserved domains/motifs distribution within the same group. Gene expression analysis uncovered their special expression patterns in different soybean tissues/organs and under various abiotic stresses. Group I and II members were mainly involved in salt and alkaline stresses. The expression of Group III members was induced/repressed by dehydration, salt and alkaline stresses, indicating their diverse roles in response to abiotic stress.

1. Introduction

As one of the most widely grown crops in the world, soybean (

Glycine max) provides an important source of plant-based protein and edible oil

[1]. However, its yield and quality are enormously hindered by germplasm resources and diverse environmental factors, especially water deficiency, high salt, and alkaline

[2]. Drought is one of the major natural disasters for the world’s agricultural production. Globally, this extreme weather phenomenon has led to cereal loss of 1820 million Mg during the past four decades

[3][4]. Soil saline–alkalization is another worldwide abiotic stress restraining land utilization, grain yield, and local economic development. According to official statistics, more than 6% of the world’s soil resources are affected by saline and alkaline. Furthermore, continuous drought has a great influence on soil salinization and salt accumulation in the root zone

[5]. Utilization and management of the saline-alkaline soil are requisite to alleviate the ever-growing population’s demand for food. Consequently, it is meaningful to focus on uncovering the molecular mechanism of plant response to abiotic stress and cultivating crops with stress resistance.

The RING E3 (Really Interesting New Gene) proteins were found to play critical roles in abiotic stress response via protein ubiquitination degradation

[6][7]. Previously, a C3H2C3 RING (Really Interesting New Gene) zinc finger domain-containing protein from

Arabidopsis was characterized and named as

MIEL1 (

MYB30-Interacting E3 Ligase1)

[8]. According to the conserved RING zinc finger domain, they were also called

CHYR (

CHY ZINC-FINGER AND RING FINGER PROTEIN) and

RZFP (

RING ZINC-FINGER PROTEIN)

[9][10]. Protein sequence alignment has proved that

MIEL1,

RZFP, and

CHYR were in the same family, with conserved CHY zinc-finger, C3H2C3-type ring finger, and rubredoxin-type fold domain

[9]. In addition, when hemerythrin domains appeared in the N-terminus of the CHY zinc finger domain, they were designated

BTS/BSTL (

BRUTUS/BRUTUS-like) in

Arabidopsis, but

HRZ (

Hemerythrin motif-containing RING-and Zinc-finger protein) in rice

[11][12][13][14]. Above all, we could uniformly define these proteins containing CHY zinc-finger, C3H2C3 -type ring finger, and rubredoxin-type fold domain as the

CHYR family.

Increasing evidence has shown the diverse roles of

CHYR genes in plant growth, development, and stress responses. MIEL1 was first found to control protein stability of MYB96 and MYB30 in balancing cuticular wax biosynthesis and defense

[8][15][16].

AtCHYR1 was reported to enhance ABA and drought responses by elevating ROS production and stomatal closure

[9]. The homologous gene of

Populus euphratica (

PeCHYR1) showed similar phenotypes, enhancing drought tolerance, stomatal closure, and H

2O

2 production

[17]. However, overexpression of

OsRZF34 (

AtCHYR1 homologous gene in rice) enhanced stomatal opening, leaf cooling and ABA insensitivity

[10].

CHYR proteins with 2–3 additional hemerythrin domains (also known as

BTS/BTSL/HRZ) were found to regulate iron response in

Arabidopsis and rice

[11][12][18].

2. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of CHYR Genes from Soybean and Arabidopsis

To identify soybean

CHYR genes, protein sequences of published

Arabidopsis CHYRs [8][9][11][12][19] were used to construct a Hidden Markov Model (HMM)

[20]. Whole soybean and

Arabidopsis protein sequences were downloaded from Phytozome to carry out the local search. Finally, 16 soybean and 7

Arabidopsis CHYR genes were identified. The 23 proteins were proven to contain at least three conserved domains, including CHY zinc-finger (PF05495), C3H2C3-type ring finger (PF13639), and zinc ribbon domain (PF14599) according to Pfam and SMART analysis. For convenience’s sake, soybean

CHYR genes were renamed

GmCHYR1 to

GmCHYR16 based on their order on the chromosomes, and genes from

Arabidopsis were relabeled as

AtCHYR1 to

AtCHYR7. Their involved information (including sequence length, hydropathicity, predicted protein location, classification, alternative name, and functions) were listed in

Table S1. As we could see from

Table S1, amino acid numbers of

GmCHYRs and

AtCHYRs ranged from 234 to 1262. Their grand average of hydropathicity was all negative, indicating that

GmCHYRs and

AtCHYRs are hydrophilic proteins. Furthermore, these

CHYR proteins were predicted to localize in the cytoplasm, or nucleus, or chloroplast. The cytoplasm and nucleus distribution of AtCHYR6/MIEL1 in

Arabidopsis cells could support this result

[8].

To further investigate the phylogenetic relationship of GmCHYRs, their protein sequences were aligned with 7 AtCHYRs. All 23

CHYR proteins contained conserved CHY zinc-finger (PF05495), C3H2C3-type ring finger (PF13639), and zinc ribbon 6 domain (PF14599) (

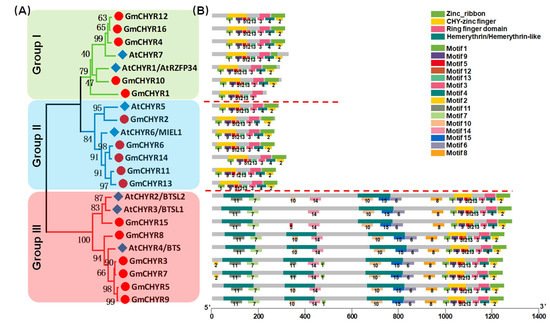

Figure S1). Then, a phylogenetic tree was generated based on this multiple alignment by using MEGA 7.0 with the Maximum-Likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replications. As shown in

Figure 1A, soybean and

Arabidopsis CHYRs could be classified into three groups according to their topological analysis and bootstrap values. In detail, both Group I and Group II consisted of 5

GmCHYRs and 2 AtCHYRs. The rest, 6

GmCHYRs and 3 AtCHYRs were allocated to Group III.

Figure 1. The phylogenetic tree and conserved domains and motifs analysis of CHYR genes in soybean and Arabidopsis. (A) Phylogenetic tree of soybean and Arabidopsis CHYR proteins, constructed by using MEGA 7.0 with the maximum-likelihood (ML) method under 1000 replications. (B) Conserved domains in GmCHYR proteins were identified by combining the SMART, PFAM, and NCBI CD database, represented by different colors. Green: Zinc_ribbon domain; Yellow: CHY-zinc finger domain; Pink: Ring finger domain; Dark green: Hemerythrin/Hemerythrin-like domain. The conserved motifs of GmCHYR proteins were analyzed by using the MEME tool. Schematic of the conserved domains and motifs were integrated by employing TBtools. The motif number was displayed below each motif.

Furthermore, their conserved domains and motifs were analyzed. As expected, all 16

GmCHYRs and 7

AtCHYRs contained CHY zinc-finger, C3H2C3-type ring finger, and zinc ribbon (

Figure 1B). Besides, there were 2-3 hemerythrin domains in the N terminus of Group III members. Group III members were also called

BTS/BTSL in

Arabidopsis, and

HRZ in rice

[12][18]. This is consistent with former reported results that there were 2

BTSL (

AtCHYR2/3) and 1

BTS (

AtCHYR4) in

Arabidopsis [12]. All of them have been reported to regulate iron homeostasis

[11]. Meanwhile, we employed the MEME program to predict conserved motifs (

Figure 1B). In accordance with conserved domains,

GmCHYRs within each group displayed similar motif distribution. Among the detected 15 motifs, motif 1, 5, 9, 12 in the N terminus made up CHY-zinc finger. Motif 3 and 4 formed the Ring finger domain. Motif 2 served as Zinc_ribbon domain. Additionally, the hemerythrin domain of Group III members constitutes motif 7, 10, 11, 14, 15. Additionally, a conserved motif 6 and 8, which was close to the hemerythrin domain, could be found in Group III members. However, their function still needs further investigation.

3. Identification and Classification of CHYR Members in Green Plants

The above results showed that only Group III members contained 2–3 additional hemerythrin domains in the N terminus, which are of great importance in regulating iron homeostasis. We wondered whether Group III

CHYR proteins gained these hemerythrin domains during evolution, or Group I and II lost these domains. Therefore, the local proteome sequences of 21 representative plant species, including Dicots, Monocots, Basal Angiosperms, Pteridophyta, Bryophyta, Chlorophyta, and Gymnosperm were searched to identify potential

CHYR genes by using the former

Arabidopsis HMM. At last, a total of 107 nonredundant sequences were obtained from 21 detected plant species (

Table 1 and

Table S2). Pfam and SMART were further used to detect the three conserved domains for

CHYR proteins, including the CHY zinc-finger domain, C3H2C3-type ring finger domain, and zinc ribbon domain.

Table 1. Overview of genes encoding CHYR proteins in plants.

| Major Lineage |

Species |

Group I |

Group II |

Group III |

| Dicots |

Vitis vinifera |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana |

2 |

2 |

3 |

| Glycine max |

5 |

5 |

6 |

| Monocots |

Zea mays |

3 |

2 |

1 |

| Oryza sativa |

3 |

2 |

2 |

| Ananas comosus |

1 |

2 |

1 |

| Musa acuminata |

1 |

1 |

3 |

| Spirodela polyrhiza |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Zostera marina |

0 |

1 |

2 |

| Basal angiosperms |

Amborella trichopoda |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Gymnosperm |

Pinus parviflora |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| Pinus radiata |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| Pinus jeffreyi |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| Pinus ponderosa |

4 |

0 |

1 |

| Picea engelmanii |

3 |

0 |

0 |

| Pteridophyta |

Selaginella moellendorffii |

1 |

0 |

2 |

| Bryophyta |

Marchantia polymorpha |

1 |

0 |

1 |

| Physcomitrella patens |

5 |

0 |

3 |

| Sphagnum fallax |

5 |

0 |

2 |

| Chlorophyta |

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii |

0 |

1 |

1 |

| Volvox carteri |

0 |

1 |

1 |

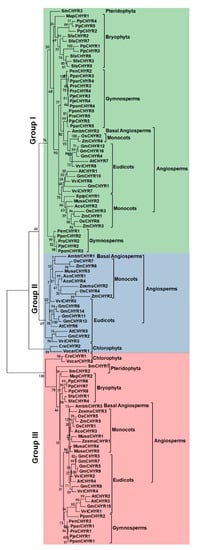

To explore their evolutionary relationship, 107

CHYR members were aligned using ML (Maximum-likelihood), NJ (Neighbor-joining), and ME (Minimum-evolution) methods to construct unrooted phylogenetic trees based on their protein sequences (

Figure 2,

Figure S2, and

Figure S3). As the three phylogenetic trees depicted, three methods presented a similar topology. According to their evolutionary relationship, 107

CHYR members could be further divided into three groups (Group I, II, III) as well. Though Group I and Group II were clustered together,

CHYR members from Bryophyta, Pteridophyta, and Gymnosperms could be only found in Group I, implying the possibility of gene acquisition during evolution. From this result, we speculated that Group II might appear after Group I. Group III did coexist with the other two groups, but was far away from the others in topology, which indicated that they might come from different ancestors. Interestingly, there were only 4

CHYR members in Chlorophyta, two of them were from

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the others were from

Volvox carteri. While

CreCHYR2 and

VocarCHYR1 were clustered with Group I and Group II,

CreCHYR1 and

VocarCHYR2 were grouped Group III, indicating the existence of

CHYR members throughout green plants evolution. A previous study has reported the up-regulation of

CreCHYR1 under iron deficiency

[21], suggesting the conserved role of Group III members in iron regulating. The above findings implied the early emergence of

CHYR members and their persistence in the evolution of green plants.

Figure 2. The Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of CHYR genes in green plants. One hundred and seven CHYR protein sequences from 21 detected plant species were aligned with ClustalW and a phylogenetic tree was generated by using MEGA7 with the maximum-likelihood method under 1000 replications. The tree was divided into three groups with green shadow in Group I, the blue shadow in Group II, and red shadow in Group III. Confidence values were listed on each node.

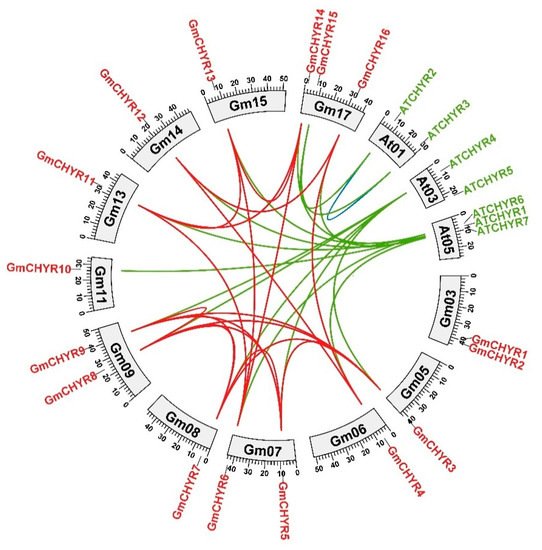

4. Homology Analysis of CHYR Genes from Soybean and Arabidopsis

According to their phylogenetic relationship, the number of

GmCHYRs is more than twice that of

AtCHYRs. Particularly,

GmCHYRs appeared in pairs. The big genome size and whole-genome duplication might be two critical reasons for gene expansion

[22], such as gene duplication in soybean

LRR-RLK genes

[23]. The homologous relationship of

GmCHYRs and

AtCHYRs was further analyzed by comparing

G. max and

A. thaliana genomic sequence through OrthoVenn2

[24]. As depicted in

Figure 3, 15 orthologous gene pairs were identified from

Arabidopsis and soybean (green line in

Figure 3). Nineteen paralogous gene pairs were characterized from soybean (red line in

Figure 3), but only one paralogous gene pair exist in

Arabidopsis (blue line in

Figure 3), which might be derived from gene expansion during whole-genome duplication that occurred in soybean, or gene loss in

Arabidopsis [25].

Figure 3. Chromosomal distribution and homology analysis of CHYR genes in the genomes of soybean and Arabidopsis. Paralogous and orthologous CHYR genes were mapped onto soybean and Arabidopsis chromosomes. Red lines connected soybean paralogous genes. Green lines indicated orthologous genes between Arabidopsis and soybean. Blue lines connected Arabidopsis paralogous genes.

To trace their duplication time,

Ka (non-synonymous rate),

Ks (synonymous rate), and

Ka/Ks ratios of 19 soybean paralogous genes were analyzed (

Table S3). All

Ka/Ks ratio of

GmCHYRs were less than 1, varied from 0.12 to 0.4, indicating that they have undergone strong purifying selection. Furthermore, their duplication time was calculated. The duplication time of Group I members varied from 9.5–43.6 Mya (million years ago) and Group II was around 11.5–46.4 Mya. This period is consistent with the latest twice whole genome duplication of soybean

[25]. However, the duplication time of

GmCHYR3/GmCHYR8,

GmCHYR5/GmCHYR8,

GmCHYR7/GmCHYR8,

GmCHYR8/GmCHYR9 pairs in Group III were greater than 155.6 Mya, which was just in line with the specific γ duplication of dicotyledon

[25]. These results uncovered that

GmCHYR expansion derived from whole-genome duplication, resulting in conserved domains and motifs.

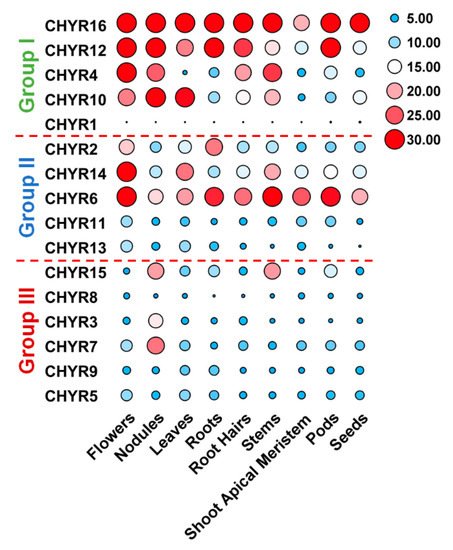

5. Expression Pattern of Soybean CHYR Genes in Different Tissues and Organs

To further look into

GmCHYRs roles in soybean development, their expression profiles were analyzed based on published data of nine tissues/organs collected in Phytozome, including flowers, nodules, leaves, roots, roots hairs, stems, shoot apical meristem, pods, and seeds

[26]. As

Figure 4 depicted, except that

GmCHYR1 showed almost no expression, the rest 15

GmCHYRs displayed specific expression across nine detected tissues/organs. Compared with Group III, Group I and II members were more likely to be expressed in all detected tissues/organs and had much higher expression values. This suggested their potential roles in soybean growth and development. Group II genes showed relatively higher expression in the flowers, suggestive of their roles in reproduction. In particular, paralogous genes

GmCHYR6 and

GmCHYR14 were all highly expressed in nine detected tissues/organs. However, Group III members preferred to be expressed in nodules, indicating their roles in nitrogen fixation. In general, paralogous genes

GmCHYR4/12/16,

GmCHYR6/11/13/14, and

GmCHYR3/7 shared similar expression patterns.

GmCHYR5/8/9 were also paralogs of

GmCHYR3/7, but they displayed opposite expression from

GmCHYR3/7. This might result from some special regulatory elements, or modification in their promoters, or just functional segregation during evolution.

Figure 4. Tissue expression profiles of GmCHYRs in soybean. The transcriptional levels of GmCHYR genes in nine tissues/organs of soybean were analyzed based on published data collected in Phytozome. A heatmap were generated by TBtools. Five to thirty were artificially set with the color scale limits according to their expression values. The color scale shows increasing expression levels from blue to red.