| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hanlin Hu | + 2393 word(s) | 2393 | 2021-11-01 07:33:03 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 84 word(s) | 2477 | 2021-11-29 09:22:46 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | + 84 word(s) | 2477 | 2021-11-29 09:31:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

Lead-free perovskites have received remarkable attention because of their nontoxicity, low-cost fabrication, and spectacular properties including controlled bandgap, long diffusion length of charge carrier, large absorption coefficient, and high photoluminescence quantum yield. Compared with the widely investigated polycrystals, single crystals have advantages of lower trap densities, longer diffusion length of carrier, and extended absorption spectrum due to the lack of grain boundaries, which facilitates their potential in different fields including photodetectors, solar cells, X-ray detectors, light-emitting diodes, and so on.

1. Introduction

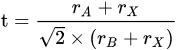

2. Various Systems of Pb-Free Single Crystal

In general, lead halide perovskites possess a universal chemical formula of APbX3, where A represents an organic/inorganic cation including Cs+, methylammonium (MA), formamidinium (FA) or their mixture, and X represents a halide anion which consists of Cl−, Br−, I−, or their mixture. In terms of structure, Pb2+ cations are separated by six neighbor X-site anions to bulid Pb-X octahedrons, which corner-share with each other to constitute the main frame and A+ intercalates the voids [23]. The replacement of Pb2+ with lead-free ions results in both the deformation in nanoscale structure and the conversion of properties because of the differences in chemical valence and ion size [24]. Therefore, LFPSCs exhibit plenty of novelty and diversity.

2.1. Sn Based Halide Perovskites

2.2. Bi/Sb Based Halide Perovskites

2.3. Other Metals Based Perovskites

2.4. Halide Double Perovskites

3. Applications

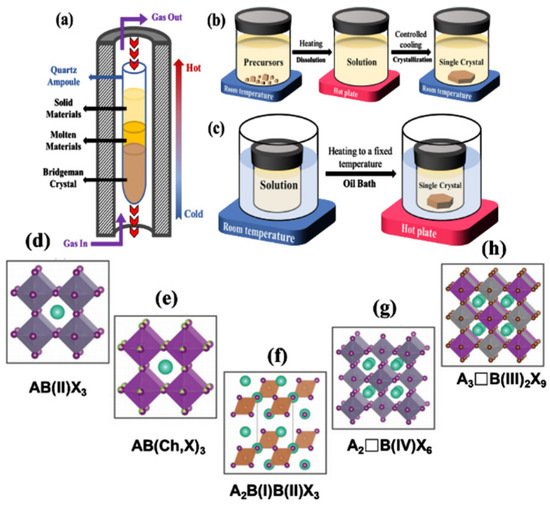

LFPSCs possess numerous fascinating optoelectronic properties in practical applications, as shown in Figure 1. Even if there is still a certain gap between lead-free and lead-based PSCs, several applications of LFPSCs have attracted attention recently. Herein, the reported achievements of applications using LFPSCs, such as photodetectors, solar cells, X-ray detectors, light emitting diodes, and other applications (Figure 2).

3.1. Photodetectors

Photodetectors capture optical signals and convert them into electrical signals instantaneously, which have been widely employed in abundant fields. The key factors of excellent photodetectors can be summarized as fast responding speed, high photocurrent intensity, and low detectivity.

Liu et al. reported a blue light photodetector with a structure of Si/SiO2/Cs3Sb2Br9/Au, the device possessed low dark current (2.4 × 10−12 A) and impressive photocurrent (3.1 × 10−8 A) at a bias of 6 V under dark condition and illuminated by 480 nm light, the response and recovery time was 0.2 ms and 3 ms respectively [42]. Compared with other lead-free perovskite-based photodetectors, Zheng et al. fabricated a nanoflake photodetector demonstrating a response speed of 24/48 ms [43].

3.2. Solar Cells

He et al. fabricated the device using synthesized FASnI3 single crystals as precursors, which possessed high purity, low defect density, and excellent stability in the air [44]. The authors demonstrated that re-dissolved single crystals forming solution effectively prevents the oxidation of Sn2+ by reducing impurities and moisture. The single crystal precursors-based films showed smooth morphology and exhibited larger and more uniform grains than conventional films. The PCE of device was 8.9% and 5.5% for spin-coated solar cells and large-scale printed cells, respectively. In addition, FASnI3 single crystal precursors-based devices retained a higher percentage of initial PCE than conventional devices. The precise controlling of crystallization to obtain near-single-crystalline film is also a viable approach to achieve higher performance.

3.3. X-ray Detectors

| LEPSCs | μτ Product (cm2V−1) | Sensitivity (μC·Gyair−1·cm−2) | Detection limit (nGyairs−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs2AgBiBr6 | 6.3 × 10−3 | 316.8 | 59.7 | [36] |

| Cs2AgBiBr6 | 5.95 × 10−3 | 1974 | 226.2 | [48] |

| MA3Bi2I9 | NA | 1947 | 83 | [49] |

| Cs3Bi2I9 | 7.97 × 10−4 | 1652.3 | 130 | [50] |

| (BA)2CsAgBiBr7 | 1.21 × 10−3 | 4.2 | NA | [51] |

| (H2MDAP)BiI5 | NA | 1.0 | NA | [52] |

3.4. Light-Emitting Diodes

3.5. Humidity Sensor and Field-Effect Transistors

4. Challenges and Prospects

References

- Zhao, Q.; Hazarika, A.; Chen, X.; Harvey, S.P.; Larson, B.W.; Teeter, G.R.; Liu, J.; Song, T.; Xiao, C.; Shaw, L.; et al. High efficiency perovskite quantum dot solar cells with charge separating heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2842.

- Wei, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, J. An overview on enhancing the stability of lead halide perovskite quantum dots and their applications in phosphor-converted LEDs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 310–350.

- Wang, H.; Kim, D.H. Perovskite-based photodetectors: Materials and devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5204–5236.

- Jeong, J.; Kim, M.; Seo, J.; Lu, H.; Ahlawat, P.; Mishra, A.; Yang, Y.; Hope, M.A.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Kim, M.; et al. Pseudo-halide anion engineering for alpha-FAPbI3 perovskite solar cells. Nature 2021, 592, 381–385.

- Dou, L.; Yang, Y.M.; You, J.; Hong, Z.; Chang, W.H.; Li, G.; Yang, Y. Solution-processed hybrid perovskite photodetectors with high detectivity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5404.

- Yin, W.-J.; Shi, T.; Yan, Y. Unusual defect physics in CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cell absorber. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 063903.

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, N.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Xiao, X.; Rudd, P.; Moran, A.; Yan, Y.; et al. Efficient sky-blue perovskite light-emitting diodes via photoluminescence enhancement. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5633.

- Shamsi, J.; Urban, A.S.; Imran, M.; De Trizio, L.; Manna, L. Metal Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Post-Synthesis Modifications, and Their Optical Properties. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3296–3348.

- Lin, K.; Xing, J.; Quan, L.N.; de Arquer, F.P.G.; Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 per cent. Nature 2018, 562, 245–248.

- Min, H.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, G.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, J.; Paik, M.J.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, M.G.; et al. Perovskite solar cells with atomically coherent interlayers on SnO2 electrodes. Nature 2021, 598, 444–450.

- Luo, J.; Hu, M.; Niu, G.; Tang, J. Lead-free halide perovskites and perovskite variants as phosphors toward light-emitting applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 31575–31584.

- Bhaumik, S.; Ray, S.; Batabyal, S.K. Recent advances of lead-free metal halide perovskite single crystals and nanocrystals: Synthesis, crystal structure, optical properties, and their diverse applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 18, 100363.

- Jiang, H.; Kloc, C. Single-crystal growth of organic semiconductors. MRS Bull. 2013, 38, 28–33.

- Deng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, J. Light-Induced Self-Poling Effect on Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Solar Cells for Increased Device Efficiency and Stability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500721.

- Akkerman, Q.A.; Raino, G.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Manna, L. Genesis, challenges and opportunities for colloidal lead halide perovskite nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 394–405.

- Song, Y.; Bi, W.; Wang, A.; Liu, X.; Kang, Y.; Dong, Q. Efficient lateral-structure perovskite single crystal solar cells with high operational stability. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 274.

- Jing, L.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, Y.; Du, S.; Ding, J.; Sun, H.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, T. Design Growth of Triangular Pyramid MAPbBr3 Single Crystal and Its Photoelectric Anisotropy between (100) and (111) Facets. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 10826–10830.

- Yang, C.; El-Demellawi, J.K.; Yin, J.; Velusamy, D.B.; Emwas, A.-H.M.; El-Zohry, A.M.; Gereige, I.; AlSaggaf, A.; Bakr, O.M.; Alshareef, H.N.; et al. MAPbI3 Single Crystals Free from Hole-Trapping Centers for Enhanced Photodetectivity. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2579–2584.

- Chen, Y.; He, M.; Peng, J.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Z. Structure and Growth Control of Organic-Inorganic Halide Perovskites for Optoelectronics: From Polycrystalline Films to Single Crystals. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500392.

- Chakraborty, S.; Xie, W.; Mathews, N.; Sherburne, M.; Ahuja, R.; Asta, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.G. Rational Design: A High-Throughput Computational Screening and Experimental Validation Methodology for Lead-Free and Emergent Hybrid Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 837–845.

- Giustino, F.; Snaith, H.J. Toward Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 1233–1240.

- Tailor, N.K.; Kar, S.; Mishra, P.; These, A.; Kupfer, C.; Hu, H.; Awais, M.; Saidaminov, M.; Dar, M.I.; Brabec, C.; et al. Advances in Lead-Free Perovskite Single Crystals: Fundamentals and Applications. ACS Mater. Lett. 2021, 3, 1025–1080.

- Akkerman, Q.A.; Manna, L. What defines a halide perovskite? ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 604–610.

- Zhao, S.; Cai, W.; Wang, H.; Zang, Z.; Chen, J. All-Inorganic Lead-Free Perovskite(-Like) Single Crystals: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Small Methods 2021, 5, 2001308.

- Scaife, D.E.; Weller, P.F.; Fisher, W.G. Crystal preparation and properties of cesium tin (II) trihalides. J. Solid State Chem. 1974, 9, 308–314.

- Chung, I.; Song, J.-H.; Im, J.; Androulakis, J.; Malliakas, C.D.; Li, H.; Freeman, A.J.; Kenney, J.T.; Kanatzidis, M.G. CsSnI3: Semiconductor or metal? High electrical conductivity and strong near-infrared photoluminescence from a single material. High hole mobility and phase-transitions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8579–8587.

- Kahmann, S.; Nazarenko, O.; Shao, S.; Hordiichuk, O.; Kepenekian, M.; Even, J.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Blake, G.R.; Loi, M.A. Negative Thermal Quenching in FASnI3 Perovskite Single Crystals and Thin Films. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 2512–2519.

- Lehner, A.J.; Fabini, D.H.; Evans, H.A.; Hébert, C.-A.; Smock, S.R.; Hu, J.; Wang, H.; Zwanziger, J.W.; Chabinyc, M.L.; Seshadri, R. Crystal and Electronic Structures of Complex Bismuth Iodides A3Bi2I9 (A = K, Rb, Cs) Related to Perovskite: Aiding the Rational Design of Photovoltaics. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7137–7148.

- McCall, K.M.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Kostina, S.S.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Wessels, B.W. Strong Electron–Phonon Coupling and Self-Trapped Excitons in the Defect Halide Perovskites A3M2I9 (A = Cs, Rb; M = Bi, Sb). Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4129–4145.

- McCall, K.M.; Liu, Z.; Trimarchi, G.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Lin, W.; He, Y.; Hadar, I.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Wessels, B.W. α-Particle Detection and Charge Transport Characteristics in the A3M2I9Defect Perovskites (A = Cs, Rb; M = Bi, Sb). ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 3748–3762.

- Zhou, L.; Liao, J.; Huang, Z.; Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Kuang, D.; Su, C. A Highly Red-Emissive Lead-Free Indium-Based Perovskite Single Crystal for Sensitive Water Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5277–5281.

- Zhou, L.; Liao, J.; Huang, Z.; Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Kuang, D. Intrinsic Self-Trapped Emission in 0D Lead-Free (C4H14N2)2In2Br10 Single Crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15435–15440.

- Slavney, A.H.; Hu, T.; Lindenberg, A.M.; Karunadasa, H.I. A Bismuth-Halide Double Perovskite with Long Carrier Recombination Lifetime for Photovoltaic Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2138–2141.

- Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Guo, X.; Huang, Z.; Ting, H.; Sun, W.; Zhong, X.; Wei, S. The dawn of lead-free perovskite solar cell: Highly stable double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 film. Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1700759.

- Ning, W.; Gao, F. Structural and functional diversity in lead-free halide perovskite materials. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1900326.

- Pan, W.; Wu, H.; Luo, J.; Deng, Z.; Ge, C.; Chen, C.; Jiang, X.; Yin, W.-J.; Niu, G.; Zhu, L.; et al. Cs2AgBiBr6 single-crystal X-ray detectors with a low detection limit. Nat. Photonics 2017, 11, 726–732.

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhou, C.; Chung, C.-C.; Hany, I. Optical and electrical properties of all-inorganic Cs2AgBiBr6 double perovskite single crystals. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 23459–23464.

- Steele, J.A.; Pan, W.; Martin, C.; Keshavarz, M.; Debroye, E.; Yuan, H.; Banerjee, S.; Fron, E.; Jonckheere, D.; Kim, C.W.; et al. Photophysical Pathways in Highly Sensitive Cs2 AgBiBr6 Double-Perovskite Single-Crystal X-Ray Detectors. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1804450.

- Zhang, Z.; Chung, C.-C.; Huang, Z.; Vetter, E.; Seyitliyev, D.; Sun, D.; Gundogdu, K.; Castellano, F.N.; Danilov, E.O.; Yang, G. Towards radiation detection using Cs2AgBiBr6 double perovskite single crystals. Mater. Lett. 2020, 269, 127667.

- Keshavarz, M.; Debroye, E.; Ottesen, M.; Martin, C.; Zhang, H.; Fron, E.; Küchler, R.; Steele, J.A.; Bremholm, M.; Van de Vondel, J. Tuning the Structural and Optoelectronic Properties of Cs2AgBiBr6 Double-Perovskite Single Crystals through Alkali-Metal Substitution. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001878.

- Yin, H.; Xian, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wen, X.; Rahman, N.U.; Long, Y.; Jia, B.; Fan, J.; Li, W. An Emerging Lead-Free Double-Perovskite Cs2AgFeCl6: In Single Crystal. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002225.

- Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, C.; Nie, P.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; et al. Lead-Free Cs3Sb2Br9 Single Crystals for High Performance Narrowband Photodetector. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2001072.

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Luo, P.; Nie, A.; Zhu, H.; Gan, L.; Zhuge, F.; Ma, Y.; Song, H.; et al. Submillimeter and lead-free Cs3Sb2Br9 perovskite nanoflakes: Inverse temperature crystallization growth and application for ultrasensitive photodetectors. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019, 4, 1372–1379.

- He, L.; Gu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Dang, Y.; Liang, C.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y.; Tao, X. Efficient anti-solvent-free spin-coated and printed Sn-perovskite solar cells with crystal-based precursor solutions. Matter 2020, 2, 167–180.

- Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Luo, J.; Sun, Z. Dimensional Reduction of Cs2AgBiBr6: A 2D Hybrid Double Perovskite with Strong Polarization Sensitivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3429–3433.

- Shi, C.; Ye, L.; Gong, Z.-X.; Ma, J.-J.; Wang, Q.-W.; Jiang, J.-Y.; Hua, M.-M.; Wang, C.-F.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Two-Dimensional Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Rare-Earth Double Perovskite Ferroelectrics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 545–551.

- Guo, W.; Liu, X.; Han, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Hong, M.; Luo, J.; Sun, Z. Room-Temperature Ferroelectric Material Composed of a Two-Dimensional Metal Halide Double Perovskite for X-ray Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13879–13884.

- Yin, L.; Wu, H.; Pan, W.; Yang, B.; Li, P.; Luo, J.; Niu, G.; Tang, J. Controlled cooling for synthesis of Cs2AgBiBr6 single crystals and its application for X-ray detection. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1900491.

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; He, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhao, K.; Sun, H.; Lu, R. Inch-size 0D-structured lead-free perovskite single crystals for highly sensitive stable X-ray imaging. Matter 2020, 3, 180–196.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Ye, H.; Yang, Z.; You, J.; Liu, M.; He, Y.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Liu, S. Nucleation-controlled growth of superior lead-free perovskite Cs3Bi2I9 single-crystals for high-performance X-ray detection. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2304.

- Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Ji, C.; Han, S.; Xu, Y.; Luo, J.; Sun, Z. Exploring Lead-Free Hybrid Double Perovskite Crystals of (BA) 2CsAgBiBr7 with Large Mobility-Lifetime Product toward X-Ray Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 15757–15761.

- Tao, K.; Li, Y.; Ji, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, Z.; Han, S.; Sun, Z.; Luo, J. A Lead-Free Hybrid Iodide with Quantitative Response to X-ray Radiation. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 5927–5932.

- Zhang, R.; Mao, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, W.; Wumaier, T.; Wei, D.; Deng, W.; Han, K. Air-Stable, Lead-Free Zero-Dimensional Mixed Bismuth-Antimony Perovskite Single Crystals with Ultra-broadband Emission. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 2725–2729.

- Li, Z.; Song, G.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, T.; Lin, Z.; Xie, R.J. Realizing Tunable White Light Emission in Lead-Free Indium(III) Bromine Hybrid Single Crystals through Antimony(III) Cation Doping. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 10164–10172.

- Jing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Molokeev, M.S.; Lin, Z.; Xia, Z. Sb3+ Dopant and Halogen Substitution Triggered Highly Efficient and Tunable Emission in Lead-Free Metal Halide Single Crystals. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 5327–5334.