| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Luis D'Marco | + 1989 word(s) | 1989 | 2021-09-09 10:41:36 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1989 | 2021-10-26 12:26:57 | | |

Video Upload Options

The involvement of impaired alpha (α) cell function has been recognized as playing an essential role in several diseases, since hyperglucagonemia has been evidenced in both Type 1 and T2DM. This phenomenon has been attributed to intra-islet defects, like modifications in pancreatic α cell mass or dysfunction in glucagon’s secretion. Emerging evidence has shown that chronic hyperglycaemia provokes changes in the Langerhans’ islets cytoarchitecture, including α cell hyperplasia, pancreatic beta (β) cell dedifferentiation into glucagon-positive producing cells, and loss of paracrine and endocrine regulation due to β cell mass loss. Other abnormalities like α cell insulin resistance, sensor machinery dysfunction, or paradoxical ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP) opening have also been linked to glucagon hypersecretion.

1. Introduction

2. Alpha Cell Physiology: From Secretion to Regulation

The human pancreas contains 1–2 million islets, each measuring 50–100 μm in diameter and containing ∼2000 cells on average. However, islet cells are only 2% of the overall pancreatic mass. It is notable that up to 65% of the human islet cells are α cells [8]. All islet cells originate from the endoderm. Its differentiation into each islet linage is mediated by the pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (Pdx1) and neurogenin-3 (Ngn3) genes. The further evolution of α cells requires both aristaless-related homeobox (Arx) and forkhead box protein A2 (Fox-A2) action in addition to low expression levels of paired box 4 (Pax4). Other factors important for α cell differentiation include MAF BZIP Transcription Factor B (MafB), NK6 Homeobox (Nkx6.1; Nkx6.2), Pax6 [9], and RNA Paupar (PAX6 Upstream Antisense RNA). The latter is a novel long noncoding that has been shown to regulate α cell development through alternative splicing of Pax6 [10].

Glucagon is the primary α cell hormone product. It is derived from the proteolysis of the 160-aminoacid pre-pro-glucagon peptide coded by its gene located in 2q24.216. This gene is strongly expressed in α cells, the brain, and L-cells of the gut. Under normal conditions, α cells synthetize glucagon via proconvertase 2 post translational proteolysis, while L-cells produce glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) via proconvertase 1/3 pathway.

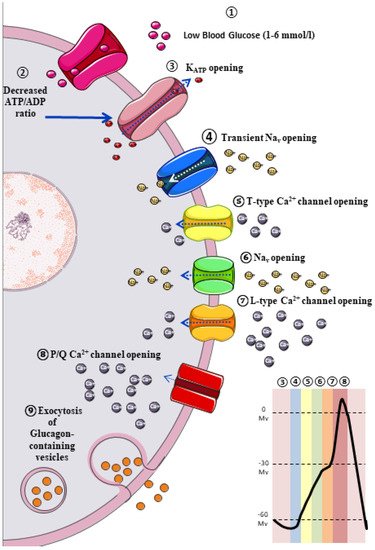

The classic model of glucagon secretion regulation is explained by glucose-medicated glucagon exocytosis. Anatomically, pancreatic islets are highly vascularized to ensure a rapid glucose and aminoacidic sensing. A glycaemic drop near to threshold stimulates glucagon release [11]. The cellular mechanism behind this glucose-dependent regulation of glucagon secretion is described in Figure 1.

3. Extrinsic Model for the Regulation of Glucagon Secretion: Neurohormonal Mechanism

3.1. Paracrine Regulation

Omar-Hmeadi et al. observed a lack of inhibition in glucagon exocytosis by hyperglycaemia, somatostatin, or insulin in intact islets in α cells from T2DM cadaveric. Instead, hyperglycaemia inhibits α cell exocytosis, but not in the T2DM donor’s α cell or when paracrine inhibition by insulin or somatostatin is blocked. A reduced Surface expression of Somatostatin-receptor-2 in islet from T2DM donors suggests somatostatin resistance, and consequently, elevated glucagon in T2DM may reflect α cell insensitivity to paracrine inhibition during hyperglycaemia [12].

3.2. Autocrine Regulation

3.3. Juxtacrine Regulation

3.4. Endocrine Regulation

4. Hyperglucagonaemia and α Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes

Extensive emerging evidence has been published among the “bi-hormonal theory” in T2DM pathogenesis in which the coexistence of hyperglucagonemia and relative insulin deficiency increase gluconeogenesis and exacerbates peripheral IR [28], leading to overt T2DM development. Currently, there is some consensus regarding hyperglucagonemia origin. This is centred on two possible mechanisms: (1) a progressive loss in the regulatory mechanisms in the secretion patterns due to α cells functional alterations [29][30], or (2) modification in both the islet microarchitecture and cellularity [31][32][33][34].

4.1. Structural Alterations in Pancreatic Islet

Conclusive evidence has demonstrated a β cell mass reduction and a concomitant decrease in insulin secretion in subjects with long-standing T2DM [35][36] and a sensible fall in GABA and serotonin release, which are crucial paracrine regulators of glucagon secretion, as explained previously. However, post-mortem studies have reported an increased α cell mass in subjects with diabetes. Nonetheless, the evidence is not conclusive [36]. This finding can be related to a loss of α cell regulating factors or a compensatory mechanism secondary to β cells mass loss [36]. Nevertheless, multiple studies have reported that an elevation of Interleukin 6 (IL-6) circulating levels in T2DM adult mice is possibly linked with an expansion of α cell mass and hyperglucagonemia [37], suggesting that α cell proliferation in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) is probably IL-6-dependent [38].

4.2. Alpha Pancreatic Cell Dysfunction, Energetic Sensors, and Ionic Channels

References

- Brown, A.E.; Walker, M. Genetics of Insulin Resistance and the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2016, 18, 75.

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223.

- Cantley, J.; Ashcroft, F.M. Q&A: Insulin secretion and type 2 diabetes: Why do β-cells fail? BMC Biol. 2015, 13, 33.

- Unger, R.H.; Orci, L. The essential role of glucagon in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1975, 305, 14–16.

- Reaven, G.M.; Chen, Y.D.; Golay, A.; Swislocki, A.L.; Jaspan, J.B. Documentation of hyperglucagonemia throughout the day in nonobese and obese patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1987, 64, 106–110.

- Lotfy, M.; Kalasz, H.; Szalai, G.; Singh, J.; Adeghate, E. Recent Progress in the Use of Glucagon and Glucagon Receptor Antagonists in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus. Open Med. Chem. J. 2014, 8, 28–35.

- Sandoval, D.A.; D’Alessio, D.A. Physiology of proglucagon peptides: Role of glucagon and GLP-1 in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 513–548.

- Wendt, A.; Eliasson, L. Pancreatic α-cells—The unsung heroes in islet function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 103, 41–50.

- Bramswig, N.C.; Kaestner, K.H. Transcriptional regulation of α-cell differentiation. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13 (Suppl. S1), 13–20.

- Singer, R.A.; Arnes, L.; Cui, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Guney, M.A.; Burnum-Johnson, K.E.; Rabadan, R.; Ansong, C.; Orr, G.; et al. The Long Noncoding RNA Paupar Modulates PAX6 Regulatory Activities to Promote Alpha Cell Development and Function. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 1091–1106.e8.

- Gromada, J.; Franklin, I.; Wollheim, C.B. Alpha-cells of the endocrine pancreas: 35 years of research but the enigma remains. Endocr. Rev. 2007, 28, 84–116.

- Omar-Hmeadi, M.; Lund, P.-E.; Gandasi, N.R.; Tengholm, A.; Barg, S. Paracrine control of α-cell glucagon exocytosis is compromised in human type-2 diabetes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1896.

- Tian, J.; Dang, H.; Chen, Z.; Guan, A.; Jin, Y.; Atkinson, M.A.; Kaufman, D.L. γ-Aminobutyric acid regulates both the survival and replication of human β-cells. Diabetes 2013, 62, 3760–3765.

- Leibiger, B.; Moede, T.; Muhandiramlage, T.P.; Kaiser, D.; Vaca Sanchez, P.; Leibiger, I.B.; Berggren, P.-O. Glucagon regulates its own synthesis by autocrine signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 20925–20930.

- Yan, H.; Gu, W.; Yang, J.; Bi, V.; Shen, Y.; Lee, E.; Winters, K.A.; Komorowski, R.; Zhang, C.; Patel, J.J.; et al. Fully human monoclonal antibodies antagonizing the glucagon receptor improve glucose homeostasis in mice and monkeys. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 329, 102–111.

- Li, X.C.; Zhuo, J.L. Targeting glucagon receptor signalling in treating metabolic syndrome and renal injury in Type 2 diabetes: Theory versus promise. Clin. Sci. 2007, 113, 183–193.

- Petersen, K.F.; Sullivan, J.T. Effects of a novel glucagon receptor antagonist (Bay 27-9955) on glucagon-stimulated glucose production in humans. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 2018–2024.

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gromada, J.; Sewing, S.; Berggren, P.-O.; Buschard, K.; Salehi, A.; Vikman, J.; Rorsman, P.; Eliasson, L. Glucagon stimulates exocytosis in mouse and rat pancreatic alpha-cells by binding to glucagon receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 198–212.

- Liu, Z.; Kim, W.; Chen, Z.; Shin, Y.-K.; Carlson, O.D.; Fiori, J.L.; Xin, L.; Napora, J.K.; Short, R.; Odetunde, J.O.; et al. Insulin and glucagon regulate pancreatic α-cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16096.

- Hutchens, T.; Piston, D.W. EphA4 Receptor Forward Signaling Inhibits Glucagon Secretion From α-Cells. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3839–3851.

- Liu, W.; Kin, T.; Ho, S.; Dorrell, C.; Campbell, S.R.; Luo, P.; Chen, X. Abnormal regulation of glucagon secretion by human islet alpha cells in the absence of beta cells. EBioMedicine 2019, 50, 306–316.

- Reissaus, C.A.; Piston, D.W. Reestablishment of Glucose Inhibition of Glucagon Secretion in Small Pseudoislets. Diabetes 2017, 66, 960–969.

- Kania, A.; Klein, R. Mechanisms of ephrin–Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 240–256.

- Darling, T.K.; Lamb, T.J. Emerging Roles for Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands in Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1473.

- Bagger, J.I.; Knop, F.K.; Lund, A.; Vestergaard, H.; Holst, J.J.; Vilsbøll, T. Impaired regulation of the incretin effect in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 737–745.

- Piro, S.; Mascali, L.G.; Urbano, F.; Filippello, A.; Malaguarnera, R.; Calanna, S.; Rabuazzo, A.M.; Purrello, F. Chronic exposure to GLP-1 increases GLP-1 synthesis and release in a pancreatic alpha cell line (α-TC1): Evidence of a direct effect of GLP-1 on pancreatic alpha cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90093.

- Holst, J.J.; Christensen, M.; Lund, A.; de Heer, J.; Svendsen, B.; Kielgast, U.; Knop, F.K. Regulation of glucagon secretion by incretins. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13 (Suppl. S1), 89–94.

- Patarrão, R.S.; Lautt, W.W.; Macedo, M.P. Acute glucagon induces postprandial peripheral insulin resistance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127221.

- Moon, J.S.; Won, K.C. Pancreatic α-Cell Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes: Old Kids on the Block. Diabetes Metab. J. 2015, 39, 1–9.

- D’Alessio, D. The role of dysregulated glucagon secretion in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2011, 13, 126–132.

- Campbell-Thompson, M.; Tang, S.-C. Pancreas Optical Clearing and 3-D Microscopy in Health and Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 644826.

- Masini, M.; Martino, L.; Marselli, L.; Bugliani, M.; Boggi, U.; Filipponi, F.; Marchetti, P.; De Tata, V. Ultrastructural alterations of pancreatic beta cells in human diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2017, 33, e2894.

- Willcox, A.; Gillespie, K.M. Histology of Type 1 Diabetes Pancreas. In Type-1 Diabetes; Gillespie, K.M., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1433, pp. 105–117. ISBN 978-1-4939-3641-0.

- Mateus Gonçalves, L.; Almaça, J. Functional Characterization of the Human Islet Microvasculature Using Living Pancreas Slices. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 11, 602519.

- Rojas, J.; Bermudez, V.; Palmar, J.; Martínez, M.S.; Olivar, L.C.; Nava, M.; Tomey, D.; Rojas, M.; Salazar, J.; Garicano, C.; et al. Pancreatic Beta Cell Death: Novel Potential Mechanisms in Diabetes Therapy. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 2018, 9601801.

- Mizukami, H.; Takahashi, K.; Inaba, W.; Tsuboi, K.; Osonoi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Yagihashi, S. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and autophagy deficits in the decline of β-cell mass in Japanese type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1966–1974.

- Ellingsgaard, H.; Ehses, J.A.; Hammar, E.B.; Van Lommel, L.; Quintens, R.; Martens, G.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Pattou, F.; Berney, T.; Pipeleers, D.; et al. Interleukin-6 regulates pancreatic alpha-cell mass expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13163–13168.

- Cai, Y.; Yuchi, Y.; De Groef, S.; Coppens, V.; Leuckx, G.; Baeyens, L.; Van de Casteele, M.; Heimberg, H. IL-6-dependent proliferation of alpha cells in mice with partial pancreatic-duct ligation. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1420–1427.

- Hamilton, A.; Zhang, Q.; Salehi, A.; Willems, M.; Knudsen, J.G.; Ringgaard, A.K.; Chapman, C.E.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, A.; Surdo, N.C.; Zaccolo, M.; et al. Adrenaline Stimulates Glucagon Secretion by Tpc2-Dependent Ca2+ Mobilization from Acidic Stores in Pancreatic α-Cells. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1128–1139.

- Zhang, Q.; Ramracheya, R.; Lahmann, C.; Tarasov, A.; Bengtsson, M.; Braha, O.; Braun, M.; Brereton, M.; Collins, S.; Galvanovskis, J.; et al. Role of KATP channels in glucose-regulated glucagon secretion and impaired counterregulation in type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 871–882.

- Knudsen, J.G.; Hamilton, A.; Ramracheya, R.; Tarasov, A.I.; Brereton, M.; Haythorne, E.; Chibalina, M.V.; Spégel, P.; Mulder, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Dysregulation of Glucagon Secretion by Hyperglycemia-Induced Sodium-Dependent Reduction of ATP Production. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 430–442.e4.

- Adam, J.; Ramracheya, R.; Chibalina, M.V.; Ternette, N.; Hamilton, A.; Tarasov, A.I.; Zhang, Q.; Rebelato, E.; Rorsman, N.J.G.; Martín-Del-Río, R.; et al. Fumarate Hydratase Deletion in Pancreatic β Cells Leads to Progressive Diabetes. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 3135–3148.

- Pareek, A.; Chandurkar, N.; Naidu, K. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1800.

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128.

- Basco, D.; Zhang, Q.; Salehi, A.; Tarasov, A.; Dolci, W.; Herrera, P.; Spiliotis, I.; Berney, X.; Tarussio, D.; Rorsman, P.; et al. α-cell glucokinase suppresses glucose-regulated glucagon secretion. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 546.

- Wang, P.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Xi, S. Effects of a Novel Glucokinase Activator, HMS5552, on Glucose Metabolism in a Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 1–9.