Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tian Tian | + 1716 word(s) | 1716 | 2021-09-03 04:54:11 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | -3 word(s) | 1713 | 2021-10-14 11:29:04 | | | | |

| 3 | Vicky Zhou | -5 word(s) | 1711 | 2021-10-14 11:30:43 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Tian, T. Rural Planning. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15029 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Tian T. Rural Planning. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15029. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Tian, Tian. "Rural Planning" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15029 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Tian, T. (2021, October 14). Rural Planning. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/15029

Tian, Tian. "Rural Planning." Encyclopedia. Web. 14 October, 2021.

Copy Citation

Rural planning is a broad academic term and human practice covering a range of topics, such as rural landscape, industry development, livelihoods of villagers and farmers, environmental conservation, and health care delivery. The objective of rural planning is to achieve rural development through the allocation and management of resources, mediated by developmentalist configuration and local communities. Rural planning could be organized at different levels, from global, national, and regional plans to plans at a village level. The time span of a rural planning is also very diverse, ranging from years to decades.

rural planning

China

development

statism

neoliberalism

1. Introduction: Rural Planning in a State of Flux

Through rural planning, social groups cast their ideas about development onto the rural space (industries, residents, and landscape). Therefore, at one time, the rural space could be described as pastoral and convivial, and at another time, it is termed as backward and peripheral. The rural space could also be seen through different lenses, such as capitalism or socialism, modernism or traditionalism, and productivism or consumerism.

Historically, it was only from the 20th century that we could truly speak of a nuanced and explicit state-sponsored rural planning and policy [1]. Ever since then, rural planning has extensively and quickly sprawled with development theories.

Since the 1930s, when a group of reformers labelled “Regionalists”, around Howard Odum, sought to “fix the problems and backwardness of rural areas” on a regional basis and thus controlled local industrialization in America [1][2][3], agro-industrial rural development strategies have been the mainstream both in developed countries and developing countries. Two strategies are the “agriculture for industrialization” strategy embodied in the Lewis two-sector model [4], and the “industrialize the agriculture” strategy, which is associated with the continued efforts of producers and manufactures to reduce and/or regularize the importance of nature in the food production process [5]. These agro-industrial rural development strategies are devoted to providing physical infrastructure and financial institutions, and invest in human capital, technical innovation, and social cooperatives to improve production efficiency.

In the 1930s, supply-management programs and environmental conservation were put on the agenda in North America and Europe, which was a turning point in rural planning policies. It has been widely identified that rural development should surpass the agro-industrial strategies, including the “agriculture for industrialization” strategy and the “industrialize the agriculture” strategy [5]. The agro-ruralist developmental strategies were revived again when modern states recovered from the Second World War and after the economic depression in the 1980s [1]. Attractive landscapes and leisure amenities needed to be considered under the multi-functional agriculture theory perspective and sustainable rural development paradigm. Farmers were now supposed to have dual identities: agricultural producers and stewards of the landscape. Process approaches [6] in rural planning were deployed with different stakeholders, underlining the empowerment of marginalized social groups.

Theories of rural planning and expectations of rural areas are variable, and evolve over time, and similarities and differences exist among different regions. Ellis and Biggs concluded that a first “paradigm shift” occurred in the 1960s, when small-farm agriculture switched to being considered the engine of development. The second “paradigm shift” occurred during the 1980s and 1990s, moving from the top-down or “blueprint” approach, in which rural actors were not actively involved, to the bottom-up, grassroots, or “process” approaches [6]. Frouws revealed three contested rural discourses in the Netherlands—the agri-ruralist discourse, the utilitarian discourse, and the hedonist discourse [7]. Marsden suggested three models—the mutable agro-industrial model, the bureaucratic “hygienic” model, and the relativist model—which obscure and constrain the agroecological and ecological modernization framework from taking hold, which is a more effective rural development dynamic [5]. Among these models, there is an “ascendance of certain aesthetic representations of the countryside over previous economic ones” [8], mostly because rural areas in the post-agrarian era are considered an amenity that provides the aesthetic experience of being closer to nature or a taste of rural idyll [9].

Among these enormous and complicated arguments, rural planning only has one constant attribute: it is always in a state of flux [10] (p. 9). The objectives of rural planning have evolved over the years and have broadened away from agricultural issues.

2. Six Evolving Themes and Narratives of Rural Planning in China

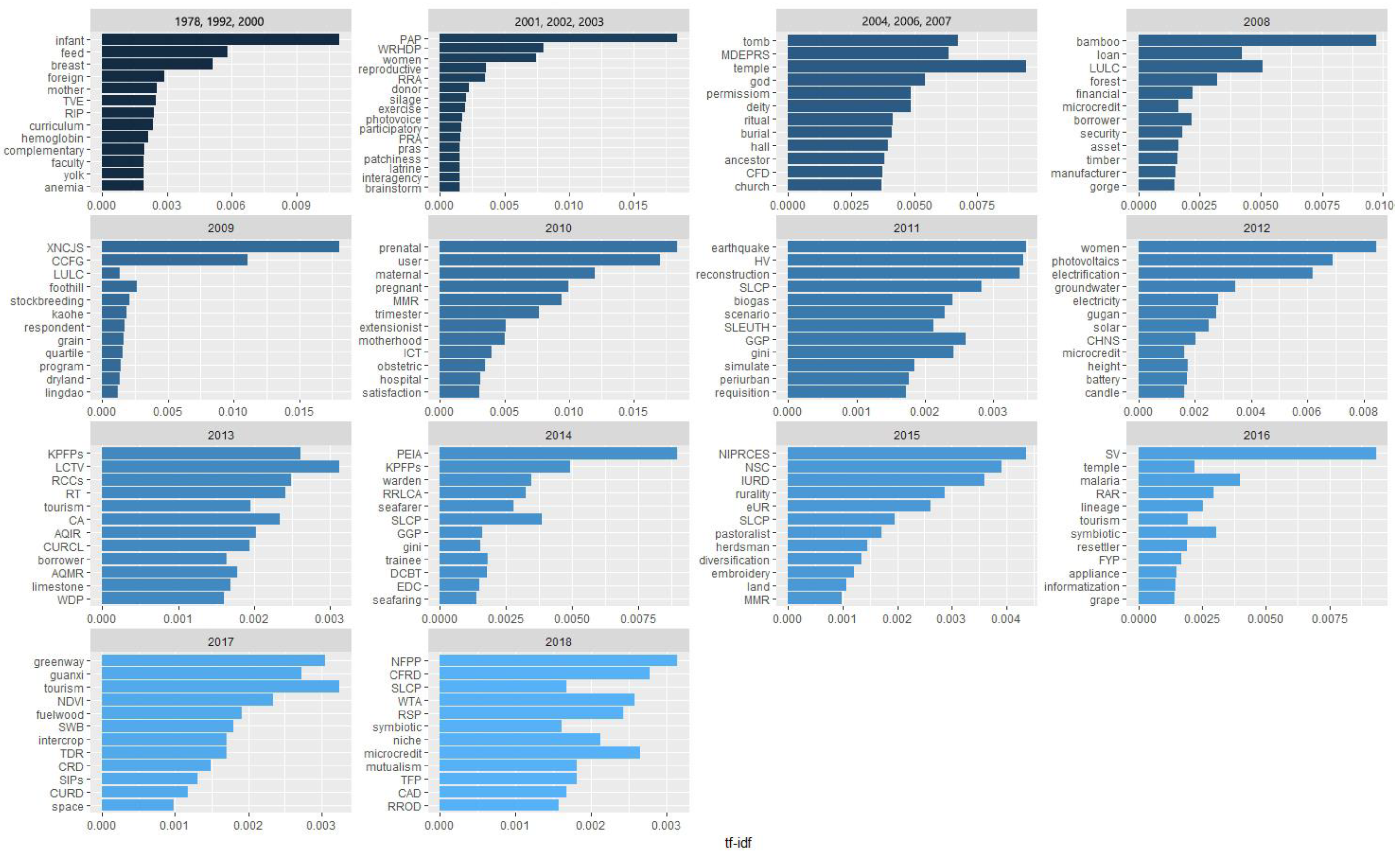

The measure tf-idf allowed us to find terms that are characteristic for a particular year (or several years) over all publications. We applied a text mining approach determining tf-idf on a yearly basis, starting in 2008. Because of the limited number of papers published before 2008, the publications between 1978 and 2007 were divided into three groups (Figure 1). After a thorough review and synthesis of the literature, considering the terms in Figure 1, six themes were revealed.

Figure 1. Terms with the highest tf-idf in annual publications concerning rural planning in China. Data last updated 24 May 2018.

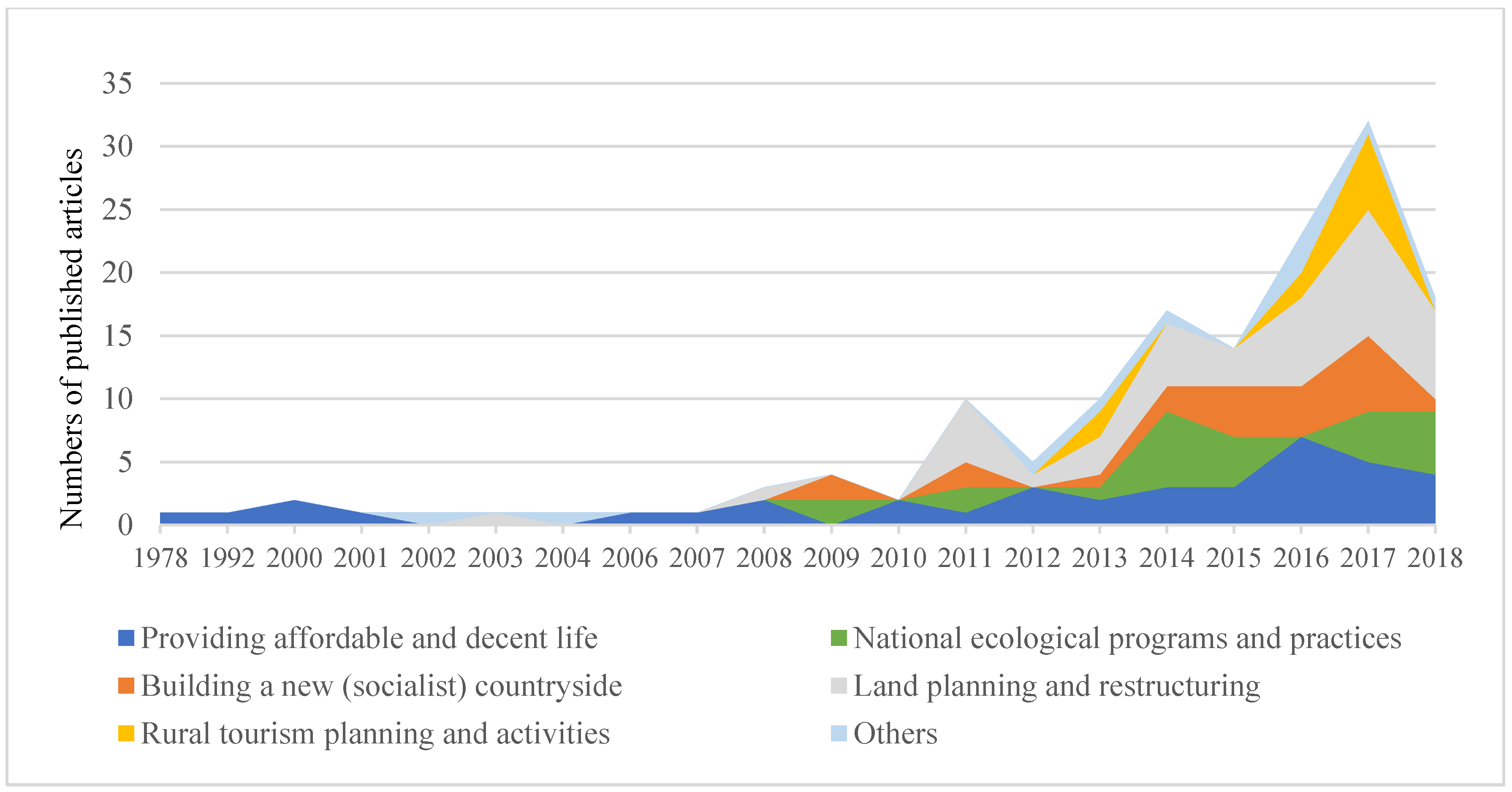

In the last decade, publications concerning rural planning in China have started to increase covering diverse themes, which could be classified along six main topics: providing affordable and decent life under industrialization and urbanization progress; national ecological programs and practices, building a new (socialist) countryside and rural−urban relationship in planning; land planning and restructuring; rural tourism planning and activities; and other themes, including women in rural planning, cultural space, and PRA. Figure 2 shows the distribution trend of the six themes. Academic research on rural planning in China was originally only focused on the theme of providing affordable and decent life under industrialization and urbanization progress. Since 2009, the themes regarding national ecological programs and building a new (socialist) countryside have become prevalent. They were followed by the theme of land planning and restructuring, which has become the most dominant research topic recently. Finally, rural tourism appeared as a new subject in the last years.

Figure 2. Historical distribution of evolving themes concerning rural planning in China. Data last updated 24 May 2018.

3. Conclusions: The Pursuit of Development behind Heterogeneous Ideologies

Research and practices on rural planning in China are heterogeneous. Both agro-industrial and agro-ruralist ideologies exist at the same time. On the one hand, “building a modernized countryside” aimed to provide an affordable and decent life under industrialization and urbanization progress; on the other hand, “building the countryside more like the countryside” yielded a lot of action, especially in the theme of rural tourism, which underlined a highly nostalgic and romanticized view of rural life. This paradox co-exists especially in the theme focused on land planning and restructuring and building a new (socialist) countryside. Some planners and governments endeavored to either urbanize villages or resettle villagers in urban areas [11]. Some planners sought to avoid replicating urban settlements in rural areas by developing recognizably “pastoral” villages, an approach that is being widely echoed in the relatively new discipline of rural spatial planning in China [12].

Scientific rationalism appeared together with humanism. Rural planning could be more strategic, systematic, scientific, data-based, and security-oriented, especially in geographical and ecological perspectives [13][14]. However, humanism is the epistemological premise of sociology and anthropology with a focus on rural society, culture, relationships, and interactions between social groups and society. Several studies in the field of geography also included a symbiotic system with the “people oriented” idea in rural settlement restructuring [15]. However, sometimes “people oriented” development becomes “economy oriented” development, as we identified in the theme of national ecological programs [16][17].

There is a common instructional epistemology among agro-industrialism, agro-ruralism, scientific rationalism, and “economy oriented” humanism: development, which was the third most frequent term in all of collected publications. The consolidation of the discourse and strategy of development starts with the problematization of poverty, strengthened by principal mechanisms through which development has been deployed, namely, the professionalization of development knowledge and the institutionalization of development practices [18] (p. 17). In rural planning, economic growth, capital accumulation, technological advocating, and modernization are outstanding examples of development.

The prevalence of development is closely connected with statism and neoliberalism. The involvement of the state in rural planning constitutes one of the most conspicuous characteristics in modern China. The degree of involvement of the modern state in the rural areas also used to constitute one of the most noteworthy and original features of post-war history in Europe [19] (pp. 51–56). The financing and provision of research, vocational education, and extension work for agriculture has been left to the state, as well as providing much of the access to finance other types of input. The state is also involved in the commercialization of farm produce, attempting to regulate and organize markets and marketing. The state has additionally assumed that the government should be concerned rural welfare, such as education, medical service, endowment insurance. However, in China, the practice of statism is broader and deeper. The modern state assumes responsibility of the management of not only the rural economy, society, and ecology, but also rural family and culture, included birth giving, restructuring settlements [20][11], and burials [21].

At the same time, the state stands firm and attempts to bring as much rural affairs as possible into the domain of the market, moving China towards neoliberalization. Rural planning is inundated with commercialization, monetization, and financialization. The state helps to promote market-oriented rural industries [22], establish rural financial institutions [23], re-embed ecology into economic practices by payments for ecosystem services [24], frame policies on property rights of rural land [25], and market rural culture and rural image for urban dwellers [26].

Rural planning is about setting a common vision for rural areas. This is a tough task in China, “where the traditions have not yet left and modernity has not settled in” [18] (p. 218), where heterogeneous ideologies are present. While development-oriented rural planning is dominant in China under the impact of statism and neoliberalism, popular practices have not disappeared. Popular culture has been revived in the expanding space of homogeneity created by the modern state and global capital [21][27], and self-organized rural planning, democratic decision-making, and endogenous institutional innovation [28][29] are in progress.

It is a cliché that rural planning is not only for achieving economic development. However, the importance of social inclusion, local culture, biodiversity, and ecosystem integrity still should be recognized and put into practice in China. Therefore, it is crucial to always have interdisciplinary teams and multi-stakeholder participatory bodies in the process of planning. How to coordinate local communities, developmentalist configuration, and institutional mechanisms needs to be addressed to ensure that local interests and priorities are represented in rural planning. In the EU, the LEADER/CLLD local development approach has provided a good model that involves local partners in shaping the future development of the countryside.

References

- Lapping, M.B. Rural Policy and planning. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P., Marsden, T., Mooney, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 105–121.

- Odum, H.W. Case for Regional-National Social Planning. Soc. Forces 1934, 13, 6–23.

- O’Connor, A. Modernization and the rural poor: Some lessons from history. In Rural Poverty in America; Duncan, C.M., Ed.; Auburn House: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 215–233.

- Lewis, W.A. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191.

- Marsden, T. The road towards sustainable rural development: Issues of theory, policy and practice in European context. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P., Marsden, T., Mooney, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 202–212.

- Ellis, F.; Biggs, S. Evolving Themes in Rural Development 1950s–2000s. Dev. Policy Rev. 2001, 19, 437–448.

- Frouws, J. The contested redefinition of the countryside. An analysis of rural discourses in The Netherlands. Sociol. Rural. 1998, 38, 54–68.

- Halfacree, K. Rural space: Constructing a three-fold architecture. In Handbook of Rural Studies; Cloke, P., Marsden, T., Mooney, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 44–62.

- Salamon, S. The rural household as a consumption site. In Handbook of rural studies; Cloke, P., Marsden, T., Mooney, P., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; pp. 330–343.

- Dalal-Clayton, B.; Dent, D.; Dubois, O. Rural Planning in Developing Countries; Earthscan Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2003; pp. 6–9.

- Lo, K.; Xue, L.; Wang, M. Spatial restructuring through poverty alleviation resettlement in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 496–505.

- Wilczak, J. Making the countryside more like the countryside? Rural planning and metropolitan visions in post-quake Chengdu. Geoforum 2017, 78, 110–118.

- Li, Y.; Long, H.; Liu, Y. Spatio-temporal pattern of China’s rural development: A rurality index perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 38, 12–26.

- Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Progress of research on urban-rural transformation and rural development in China in the past decade and future prospects. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1117–1132.

- Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Deng, C.; Wan, Q.; Zhang, L.; Fei, Z.; Li, H. Rural settlement restructuring based on analysis of the peasant household symbiotic system at village level: A Case Study of Fengsi Village in Chongqing, China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 485–495.

- Rodríguez, L.C.; Pascual, U.; Muradian, R.; Pazmino, N.; Whitten, S. Towards a unified scheme for environmental and social protection: Learning from PES and CCT experiences in developing countries Ecol. Economics 2011, 70, 2163–2174.

- Xu, W.; Khoshroo, N.; Bjornlund, H.; Yin, Y. Effects of “Grain for Green” reforestation program on rural sustainability in China: An AHP approach to peasant consensus of public land use policies. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 867–880.

- Escobar, A. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World; Ortner, S.B., Dirks, N.B., Eley, G., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 17, 218.

- Franklin, S.H. Rural Societies: Studies in Contemporary Europe; Pryce, R., Thorne, C., Eds.; The Macmillan Press Ltd.: London, UK; Basingstoke, UK, 1971; pp. 51–56.

- Huang, C.; Deng, L.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L. Rural Housing Land Consolidation and Transformation of Rural Villages under the “Coordinating Urban and Rural Construction Land” Policy: A Case of Chengdu City, China. Low Carbon Econ. 2013, 4, 95–103.

- Mei-Hui Yang, M. Spatial Struggles: Postcolonial Complex, State Disenchantment, and Popular Reappropriation of Space in Rural Southeast China. J. Asian Stud. 2004, 63, 719–755.

- Li, P.; Ryan, C.; Cave, J. Chinese rural tourism development: Transition in the case of Qiyunshan, Anhui—2008–2015. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 240–260.

- Zhang, Q.; Izumida, Y. Determinants of repayment performance of group lending in China: Evidence from rural credit cooperatives’ program in Guizhou province. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2013, 5, 328–341.

- Liu, Z.; Lan, J. The Effect of the Sloping Land Conversion Programme on Farm Household Productivity in Rural China. J. Dev. Stud. 2018, 54, 1041–1059.

- Su, F.; Tao, R.; Wang, H. State fragmentation and rights contestation: Rural land development rights in China. China World Econ. 2013, 21, 36–55.

- Keyim, P. Tourism and rural development in western China: A case from Turpan. Community Dev. J. 2016, 51, 534–551.

- Chen, N. Governing rural culture: Agency, space and the re-production of ancestral temples in contemporary China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 141–152.

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, H.; Cui, W. Community-based rural residential land consolidation and allocation can help to revitalize hollowed villages in traditional agricultural areas of China: Evidence from Dancheng County, Henan Province. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 188–198.

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhao, G. Social Network Analysis of Actors in Rural Development: A Case Study of Yanhe Village, Hubei Province, China. Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 869–882.

More

Information

Subjects:

Public Administration

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

7.6K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Oct 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No