| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Muhammad Ihtisham | + 1364 word(s) | 1364 | 2021-09-02 07:53:16 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 1364 | 2021-10-19 11:25:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

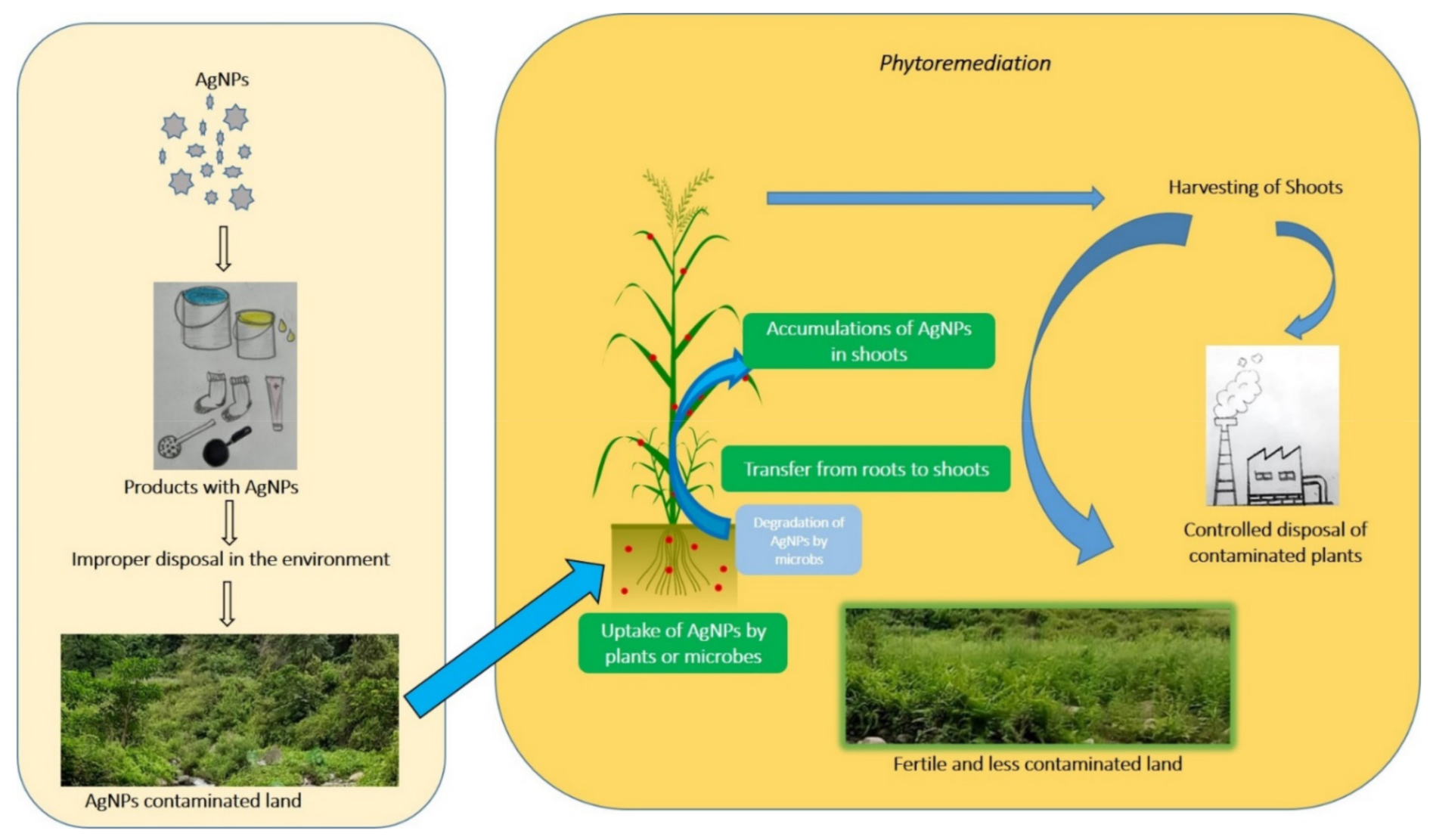

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are among the most commonly used engineered nanomaterials with medicinal, industrial, and agricultural applications. Considering the vast usage of AgNPs, there is a possibility of their release into the environment, and their potential toxicological effects on plants and animals. Apart from using the particulate form of silver, AgNPs may be transformed to silver oxide or silver sulfide via oxidation or sulfidation, respectively, and these ones impact the soil and living organisms in a variety of ways. Therefore, it is critical to address the behavior of nanoparticles in the environment and possible methods for their removal. This review focuses on three objectives to discuss this issue including: the possible pathways for the release of AgNPs into the environment; the toxicological effects of AgNPs on plants and microorganisms; and the recommended phytoremediation approaches.

1. Introduction

2. Environmental and Toxicological Effects of AgNPs

Figure 1. Potential pathway for AgNPs leakage into the environment and its remediation.

3. Conclusions

References

- De Leersnyder, I.; Rijckaert, H.; De Gelder, L.; Van Driessche, I.; Vermeir, P. High variability in silver particle characteristics, silver concentrations, and production batches of commercially available products indicates the need for a more rigorous approach. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1394.

- Market Watch. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/press-release/silvernanoparticles-market-future-scope-demands-and-projectedindustry-growths-to-2024-2019-05-09 (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- Noori, A.; Ngo, A.; Gutierrez, P.; Theberge, S.; White, J.C. Silver nanoparticle detection and accumulation in tomato. J. Nanopart. Res. 2020, 22, 131.

- Wahab, M.A.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Abdala, A. Silver Nanoparticle-Based Nanocomposites for Combating Infectious Pathogens: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 581.

- Peharec Štefanić, P.; Košpić, K.; Lyons, D.M.; Jurković, L.; Balen, B.; Tkalec, M. Phytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles on tobacco plants: Evaluation of coating effects on photosynthetic performance and chloroplast ultrastructure. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 744.

- Noori, A.; Donnelly, T.; Colbert, J.; Cai, W.; Newman, L.A.; White, J.C. Exposure of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) to silver nanoparticles and silver nitrate: Physiological and molecular response. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2020, 22, 40–51.

- Noori, A.; White, J.C.; Newman, L.A. Mycorrhizal fungi influence on silver uptake and membrane protein gene expression following silver nanoparticle exposure. J. Nanopart. Res. 2017, 19, 66.

- Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Tsitsuashvili, V.; Mandzhieva, S.; Gorovtsov, A.; Nevidomskyaya, D.; Gromakova, N. Effect of nanoparticles on crops and soil microbial communities. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 2179–2187.

- Courtois, P.; Rorat, A.; Lemiere, S.; Guyoneaud, R.; Attard, E.; Levard, C.; Vandenbulcke, F. Ecotoxicology of silver nanoparticles and their derivatives introduced in soil with or without sewage sludge: A review of effects on microorganisms, plants and animals. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 578–598.

- Ali, S.M.; Yousef, N.M.; Nafady, N.A. Application of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles for the control of land snail Eobania vermiculata and some plant pathogenic fungi. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 218904.

- Capek, I. Preparation of metal nanoparticles in water-in-oil (w/o) microemulsions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 110, 49–74.

- Reidy, B.; Haase, A.; Luch, A.; Dawson, K.A.; Lynch, I. Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle release, transformation and toxicity: A critical review of current knowledge and recommendations for future studies and applications. Materials 2013, 6, 2295–2350.

- Dobias, J.; Bernier-Latmani, R. Silver release from silver nanoparticles in natural waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 4140–4146.

- Burić, P.; Jakšić, Ž.; Štajner, L.; Sikirić, M.D.; Jurašin, D.; Cascio, C.; Calzolai, L.; Lyons, D.M. Effect of silver nanoparticles on Mediterranean sea urchin embryonal development is species specific and depends on moment of first exposure. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 50–59.

- Miao, A.-J.; Luo, Z.; Chen, C.-S.; Chin, W.-C.; Santschi, P.H.; Quigg, A. Intracellular uptake: A possible mechanism for silver engineered nanoparticle toxicity to a freshwater alga Ochromonas danica. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15196.

- Siripattanakul-Ratpukdi, S.; Ploychankul, C.; Limpiyakorn, T.; Vangnai, A.S.; Rongsayamanont, C.; Khan, E. Mitigation of nitrification inhibition by silver nanoparticles using cell entrapment technique. J. Nanopart. Res. 2014, 16, 2218.

- Vance, M.E.; Kuiken, T.; Vejerano, E.P.; McGinnis, S.P.; Hochella, M.F., Jr.; Rejeski, D.; Hull, M.S. Nanotechnology in the real world: Redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 1769–1780.

- Ivask, A.; Kurvet, I.; Kasemets, K.; Blinova, I.; Aruoja, V.; Suppi, S.; Vija, H.; Käkinen, A.; Titma, T.; Heinlaan, M. Size-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles to bacteria, yeast, algae, crustaceans and mammalian cells in vitro. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102108.

- Fabrega, J.; Luoma, S.N.; Tyler, C.R.; Galloway, T.S.; Lead, J.R. Silver nanoparticles: Behaviour and effects in the aquatic environment. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 517–531.

- Baker, T.J.; Tyler, C.R.; Galloway, T.S. Impacts of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles on marine organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 186, 257–271.

- Klitzke, S.; Metreveli, G.; Peters, A.; Schaumann, G.E.; Lang, F. The fate of silver nanoparticles in soil solution—Sorption of solutes and aggregation. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 535, 54–60.

- Nam, D.-H.; Lee, B.-C.; Eom, I.-C.; Kim, P.; Yeo, M.-K. Uptake and bioaccumulation of titanium-and silver-nanoparticles in aquatic ecosystems. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2014, 10, 9–17.

- Howe, P.D.; Dobson, S. Silver and Silver Compounds: Environmental Aspects; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Galazzi, R.M.; Júnior, C.A.L.; de Lima, T.B.; Gozzo, F.C.; Arruda, M.A.Z. Evaluation of some effects on plant metabolism through proteins and enzymes in transgenic and non-transgenic soybeans after cultivation with silver nanoparticles. J. Proteom. 2019, 191, 88–106.

- Benn, T.M.; Westerhoff, P. Nanoparticle silver released into water from commercially available sock fabrics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4133–4139.

- Lazim, Z.M.; Salmiati; Samaluddin, A.R.; Salim, M.R.; Arman, N.Z. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Removal Applying Phytoremediation System to Water Environment: An Overview. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 8, 978–984.

- Handy, R.D.; Shaw, B.J. Toxic effects of nanoparticles and nanomaterials: Implications for public health, risk assessment and the public perception of nanotechnology. Health Risk Soc. 2007, 9, 125–144.

- Owen, R.; Handy, R. Formulating the Problems for Environmental Risk Assessment of Nanomaterials; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 5582–5588.

- Pérez-de-Luque, A.; Rubiales, D. Nanotechnology for parasitic plant control. Pest Manag. Sci. Former. Pestic. Sci. 2009, 65, 540–545.

- Saharan, V. Advances in nanobiotechnology for agriculture. In Current Topics in Biotechnology & Microbiology; Dhingra, H.K., Nath Jha, P., Bajpai, P., Eds.; Lap Lambert Academic Publishing: Dudweller Landstr, Germany, 2011; pp. 156–167.

- Fernandes, J.P.; Mucha, A.P.; Francisco, T.; Gomes, C.R.; Almeida, C.M.R. Silver nanoparticles uptake by salt marsh plants–Implications for phytoremediation processes and effects in microbial community dynamics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 176–183.

- Shafer, M.M.; Overdier, J.T.; Armstong, D.E. Removal, partitioning, and fate of silver and other metals in wastewater treatment plants and effluent-receiving streams. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 1998, 17, 630–641.

- Hanks, N.A.; Caruso, J.A.; Zhang, P. Assessing Pistia stratiotes for phytoremediation of silver nanoparticles and Ag (I) contaminated waters. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 41–45.

- Purcell, T.W.; Peters, J.J. Historical impacts of environmental regulation of silver. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 1999, 18, 3–8.

- U.S. Environmnetal Proection Agency (EPA). National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Table, EPA 816-F-09-0004. 2009. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulation-table (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality, 4th ed.; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; p. 415. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44584/9789241548151_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7602427D0558C27BC51742431A74F67E?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 August 2021).

- Varner, K.; El-Badawy, A.; Feldhake, D.; Venkatapathy, R. State-of-the-Science Review: Everything Nanosilver and More; EPA/600/R-10/084:2010; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Bernas, L.; Winkelmann, K.; Palmer, A. Phytoremediation of silver species by waterweed (Egeria densa). Chemist 2017, 90, 7–13.

- Valenti, L.E.; Giacomelli, C.E. Stability of silver nanoparticles: Agglomeration and oxidation in biological relevant conditions. J. Nanopart. Res. 2017, 19, 156.

- Moreno-Garrido, I.; Pérez, S.; Blasco, J. Toxicity of silver and gold nanoparticles on marine microalgae. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 60–73.

- Lapresta-Fernández, A.; Fernández, A.; Blasco, J. Nanoecotoxicity effects of engineered silver and gold nanoparticles in aquatic organisms. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 32, 40–59.

- Navarro, E.; Baun, A.; Behra, R.; Hartmann, N.B.; Filser, J.; Miao, A.-J.; Quigg, A.; Santschi, P.H.; Sigg, L. Environmental behavior and ecotoxicity of engineered nanoparticles to algae, plants, and fungi. Ecotoxicology 2008, 17, 372–386.

- Ratte, H.T. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of silver compounds: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 1999, 18, 89–108.