| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Terence Duarte | + 2080 word(s) | 2080 | 2021-08-18 11:10:12 |

Video Upload Options

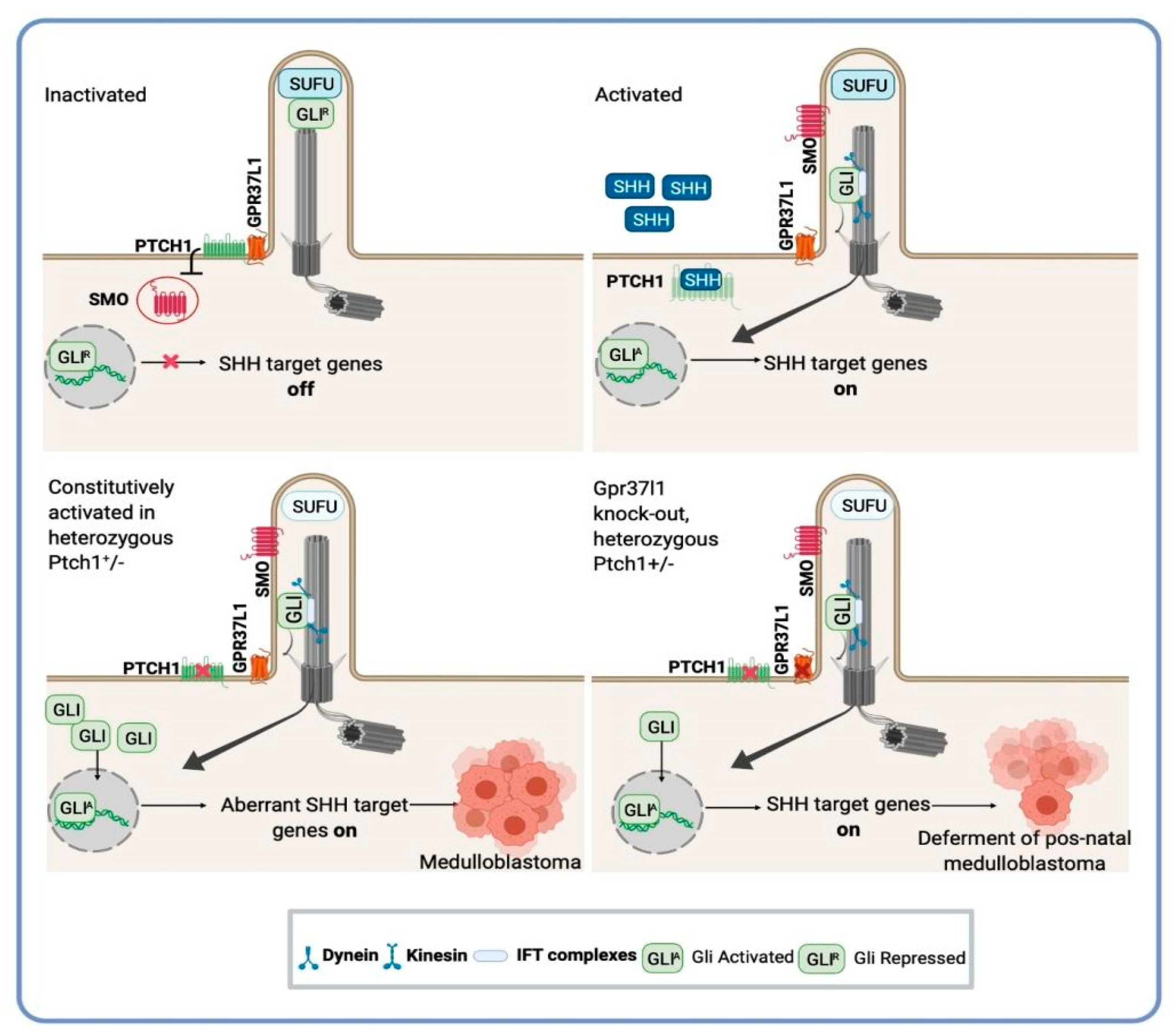

Medulloblastoma is the most prevalent malignant brain tumor in children, while it accounts for only 1–2% of adult brain tumors. Recognized as a biologically heterogeneous disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) considers there to be four molecular subgroups: wingless-activated (WNT), sonic hedgehog-activated (SHH); Group 3; and Group 4. Recently, the picture became more complex when 12 different medulloblastoma subtypes were described, including two WNT subtypes, four SHH subtypes, three group 3 subtypes, and three group 4 subtypes, with each subgroup being characterized by specific mutations, copy number variations, transcriptomic/methylomic profiles, and clinical outcomes. For the SHH subgroup MB, germline or somatic mutations and a copy-number variation are the common drivers that affect critical genes involved in SHH signaling, including PTCH1 (patched 1 homologue), SUFU (suppressor of fused homologue), and SMO (smoothened), among others

1. Introduction

The most common genetic events, which occur in both pediatric and adult tumors, are loss-of-function, mutations, or deletions in PTCH1 and SUFU , which act as negative regulators of SHH signaling [1][2][3]. Activation of mutations and amplification of SMO or GLI2 (glioma associated oncogene homologue 2) also lead to constitutive activation of the SHH pathway [4][5]. Germline and somatic TP53 mutations predominantly coincident with GLI2 amplifications and are found exclusively in children between the ages of 8 and 17 years [6][7][8][9]. Somatic TERT (telomerase) promoter hotspot mutations are also associated with the SHH subgroup [10][11]. Mutation of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) is found in more than 5% of human SHH subgroup MB cases and is associated with decreased expression of PTEN mRNA and proteins in the cerebellum [9][12]. In addition, genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) carrying mutations/overexpression of those genes have also been developed to study this medulloblastoma subgroup [13][14][15].

Medulloblastoma can also be viewed through the lens of the tumor microenvironment (TME), and its multiple roles in cancer offer an interesting way to identify the critical steps regulating medulloblastoma biology, disease progression, and overall survival [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]. In addition to tumor cells, the tumor microenvironment is characterized by diverse cell populations, including stem-like cells and tumor-associated components such as blood vessels [18], immune cells [24][25], neurons, endothelial cells, microglia [26], macrophages [27][28], and astrocytes [17][19][20][21][29]. The communication between these unique collections of cell types is implicated in therapy resistance [30][31][32], immune infiltration, and inflammation [28]. Since tumor-associated cells could be the focus of therapeutic vulnerability, a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between the tumor cells and the tumor-associated components may provide new opportunities for targeted discoveries. In the SHH subgroup MB, recent studies have highlighted that the cellular diversity within tumors has a critical role in supporting the growth of tumor cells and the robustness of cancer [17][19][21][25][27][28][29][33][34]. In MB-prone mice with a SMO mutation, the TME contains tumor cell types that exist across a spectrum of differentiation states and tumor-derived cells that express makers for astrocytic and oligodendrocytic precursors [35]. This suggests that even in a tumor with a single pathway-activation mutation, diverse mechanisms may drive tumor growth, demonstrating the need to target multiple pathways simultaneously for therapeutic effectiveness.

Astrocytes and the Medulloblastoma Microenvironment: The New Player within the Complex Ecosystem

2. Novel Targets and Therapeutic Opportunities for Medulloblastoma: A Potential Application of Astrocytes-SHH Medulloblastoma Cross-Talk Research

References

- Raffel, C.; Jenkins, R.B.; Frederick, L.; Hebrink, D.; Alderete, B.; Fults, D.W.; James, C.D. Sporadic medulloblastomas contain PTCH mutations. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 842–845.

- Taylor, M.D.; Liu, L.; Raffel, C.; Hui, C.C.; Mainprize, T.G.; Zhang, X.; Agatep, R.; Chiappa, S.; Gao, L.; Lowrance, A.; et al. Mutations in SUFU predispose to medulloblastoma. Nat. Genet. 2002, 31, 306–310.

- Brugières, L.; Pierron, G.; Chompret, A.; Paillerets, B.B.-D.; Di Rocco, F.; Varlet, P.; Pierre-Kahn, A.; Caron, O.; Grill, J.; Delattre, O. Incomplete penetrance of the predisposition to medulloblastoma associated with germ-line SUFU mutations. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 47, 142–144.

- Gibson, P.; Tong, Y.; Robinson, G.; Thompson, M.C.; Currle, D.S.; Eden, C.; Kranenburg, T.; Hogg, T.; Poppleton, H.; Martin, J.; et al. Subtypes of medulloblastoma have distinct developmental origins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 468, 1095–1099.

- Buczkowicz, P.; Ma, J.; Hawkins, C. GLI2 Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Pediatric Medulloblastoma. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 70, 430–437.

- Zhukova, N.; Ramaswamy, V.; Remke, M.; Pfaff, E.; Shih, D.J.H.; Martin, D.C.; Castelo-Branco, P.; Baskin, B.; Ray, P.N.; Bouffet, E.; et al. Subgroup-Specific Prognostic Implications of TP53 Mutation in Medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2927–2935.

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W.K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O.D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D.W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 803–820.

- Ramaswamy, V.; Remke, M.; Bouffet, E.; Bailey, S.; Clifford, S.C.; Doz, F.; Kool, M.; Dufour, C.; Vassal, G.; Milde, T.; et al. Risk stratification of childhood medulloblastoma in the molecular era: The current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 821–831.

- Da Silva, L.S.; Mançano, B.M.; de Paula, F.E.; dos Reis, M.B.; de Almeida, G.C.; Matsushita, M.; Junior, C.A.; Evangelista, A.F.; Saggioro, F.; Serafini, L.N.; et al. Expression of GNAS, TP53, and PTEN Improves the Patient Prognostication in Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Medulloblastoma Subgroup. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 957–966.

- Viana-Pereira, M.; Almeida, G.C.; Stavale, J.N.; Malheiro, S.; Clara, C.; Lobo, P.; Pimentel, J.; Reis, R. Study of hTERT and Histone 3 Mutations in Medulloblastoma. Pathobiology 2016, 84, 108–113.

- Remke, M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Peacock, J.; Shih, D.J.H.; Koelsche, C.; Northcott, P.A.; Hill, N.; Cavalli, F.M.G.; Kool, M.; Wang, X.; et al. TERT promoter mutations are highly recurrent in SHH subgroup medulloblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 917–929.

- Hartmann, W.; Digon-Söntgerath, B.; Koch, A.; Waha, A.; Endl, E.; Dani, I.; Denkhaus, D.; Goodyer, C.G.; Sörensen, N.; Wiestler, O.D.; et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3′-Kinase/AKT Signaling Is Activated in Medulloblastoma Cell Proliferation and Is Associated with Reduced Expression ofPTEN. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 3019–3027.

- Goodrich, L.V.; Milenković, L.; Higgins, K.M.; Scott, M.P. Altered neural cell fates and medulloblastoma in mouse patched mutants. Science 1997, 277, 1109–1113.

- Kimura, H.; Stephen, D.; Joyner, A.; Curran, T. Gli1 is important for medulloblastoma formation in Ptc1+/− mice. Oncogene 2005, 24, 4026–4036.

- Castellino, R.C.; Barwick, B.G.; Schniederjan, M.; Buss, M.C.; Becher, O.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Macdonald, T.J.; Brat, D.J.; Durden, D.L. Heterozygosity for Pten promotes tumorigenesis in a mouse model of medulloblastoma. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10849.

- Byrd, T.; Grossman, R.G.; Ahmed, N. Medulloblastoma-Biology and microenvironment: A review. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 29, 495–506.

- Liu, Y.; Yuelling, L.W.; Wang, Y.; Du, F.; Gordon, R.E.; O'Brien, J.A. Astrocytes promote medulloblastoma progression through hedgehog secretion. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6692–6703.

- Hambardzumyan, D.; Becher, O.J.; Rosenblum, M.K.; Pandolfi, P.P.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Holland, E.C. PI3K pathway regulates survival of cancer stem cells residing in theperivascular niche following radiation in medulloblastoma in vivo. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 436–448.

- Di Pietro, C.; La Sala, G.; Matteoni, R.; Marazziti, D.; Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. Genetic ablation of Gpr37l1 delays tumor occurrence in Ptch1 +/− mouse models of medulloblastoma. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 312, 33–42.

- Chen, K.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Cheng, C.J.; Jhan, K.Y.; Wang, L.C. Excretory/secretory products of Angiostrongyluscantonensis fifth-stage larvae induce endoplasmic reticulum stress via the Sonic hedgehog pathway in mouse astrocytes. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 317.

- Yao, M.; Ventura, P.B.; Jiang, Y.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Wang, L.; Perry, J.S.A. Astrocytic trans-Differentiation Completes a Multicellular Paracrine Feedback Lop Required for Medulloblastoma Tumor Growth. Cell 2020, 180, 502–520.e19.

- Zhou, R.; Joshi, P.; Katsushima, K.; Liang, W.; Liu, W.; Goldenberg, N.A. The emerging field of noncoding RNAs and their importance in pediatric diseases. J. Pediatr. 2020, 221, S11–S19.

- Chung, A.S.; Ferrara, N. Targeting the tumor microenvironment with Src kinase inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 775–777.

- Binnewies, M.; Roberts, E.W.; Kersten, K.; Chan, V.; Fearon, D.F.; Merad, M.; Coussens, L.M.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Hedrick, C.C.; et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 541–550.

- Gajewski, T.F.; Schreiber, H.; Fu, Y.-X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 1014–1022.

- Amarante, M.K.; Vitiello, G.A.F.; Rosa, M.H.; Mancilla, I.A.; Watanabe, M.A.E. Potential use of CXCL12/CXCR4 and sonic hedgehog pathways as therapeutic targets in medulloblastoma. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1134–1142.

- Margol, A.S.; Robison, N.J.; Gnanachandran, J.; Hung, L.T.; Kennedy, R.J.; Vali, M.; Dhall, G.; Finlay, J.L.; Epstein, A.; Krieger, M.D.; et al. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in SHH Subgroup of Medulloblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1457–1465.

- Pham, C.D.; Mitchell, D.A. Know your neighbors: Different tumor microenvironments have implications in immunotherapeutic targeting strategies across MB subgroups. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1144002.

- Cheng, Y.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Long, Y.; Cukierman, E.; Yang, Z.-J. Sustained hedgehog signaling in medulloblastoma tumoroids is attributed to stromal astrocytes and astrocyte-derived extracellular matrix. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 1208–1222.

- Raviraj, R.; Nagaraja, S.S.; Selvakumar, I.; Mohan, S.; Nagarajan, D. The epigenetics of brain tumors and its modulation during radiation: A review. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117974.

- Hirata, E.; Sahai, E. Tumor microenvironment and differential responses to therapy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2017, 7, a026781.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Tamayo-Orrego, L.; Charron, F. Recent advances in SHH medulloblastoma progression: Tumor suppressor mechanisms and the tumor microenvironment. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1823.

- Raza, M.; Prasad, P.; Gupta, P.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, T.; Rana, M.; Goldman, A.; Sehrawat, S. Perspectives on the role of brain cellular players in cancer-associated brain metastasis: Translational approach to understand molecular mechanism of tumor progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 791–804.

- Ocasio, J.; Babcock, B.; Malawsky, D.; Weir, S.J.; Loo, L.; Simon, J.M.; Zylka, M.J.; Hwang, D.; Dismuke, T.; Sokolsky, M.; et al. scRNA-seq in medulloblastoma shows cellular heterogeneity and lineage expansion support resistance to SHH inhibitor therapy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5829.

- Sofroniew, M.V. Multiple roles for astrocytes as effectors of cytokines and inflammatory mediators. Neuroscientist 2014, 20, 160–172.

- Khakh, B.S.; Sofroniew, M.V. Diversity of astrocyte functions and phenotypes in neural circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 942–952.

- Anderson, M.A.; Ao, Y.; Sofroniew, M.V. Heterogeneity of reactive astrocytes. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 565, 23–29.

- Burda, J.E.; Bernstein, A.M.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 305–315.

- Tong, X.; Ao, Y.; Faas, G.C.; Nwaobi, S.E.; Xu, J.; Haustein, M.D.; Anderson, M.A.; Mody, I.; Olsen, M.; Sofroniew, M.V.; et al. Astrocyte Kir4.1 ion channel deficits contribute to neuronal dysfunction in Huntington’s disease model mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 694–703.

- Robel, S.; Berninger, B.; Götz, M. The stem cell potential of glia: Lessons from reactive gliosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 88–104.

- Silver, J.; Miller, J.H. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 146–156.

- Zamanian, J.L.; Xu, L.; Foo, L.C.; Nouri, N.; Zhou, L.; Giffard, R.G.; Barres, B.A. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6391–6410.

- Pekny, M.; Pekna, M. Reactive gliosis in the pathogenesis of CNS diseases. Biochim. Biophys Acta. 2016, 1862, 483–491.

- Wasilewski, D.; Priego, N.; Fustero-Torre, C.; Valiente, M. Reactive astrocytes in brain metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 298.

- Placone, A.L.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A.; Searson, P.C. The role of astrocytes in the progression of brain cancer: Complicating the picture of the tumor microenvironment. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 61–69.

- Brandao, M.; Simon, T.; Critchley, G.; Giamas, G. Astrocytes, the rising stars of the glioblastoma microenvironment. Glia 2019, 67, 779–790.

- Gronseth, E.; Gupta, A.; Koceja, C.; Kumar, S.; Kutty, R.G.; Rarick, K.; Wang, L.; Ramchandran, R. Astrocytes influence medulloblastoma phenotypes and CD133 surface expression. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235852.

- Nedergaard, M.; Ransom, B.; Goldman, S.A. New roles for astrocytes: Redefining the functional architecture of the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 523–530.

- Barres, B.A. The Mystery and Magic of Glia: A perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron 2008, 60, 430–440.

- Sofroniew, M.V. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 638–647.

- Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte reactivity: Subtypes, states, and functions in cns innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 758–770.

- Traiffort, E.; Charytoniuk, D.; Watroba, L.; Faure, H.; Sales, N.; Ruat, M. Discrete localizations of hedgehog signalling components in the developing and adult rat nervous system. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 3199–3214.

- Garcia, A.D.; Petrova, R.; Eng, L.; Joyner, A.L. Sonic Hedgehog regulates discrete populations of astrocytes in the adult muse forebrain. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 13597–13608.

- Jiao, J.; Chen, D.F. Induction of neurogenesis in nonconventional neurogenic regions of the adult central nervous systeby niche astrocyte-produced signals. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 1221–1230.

- Gonzalez-Reyes, L.E.; Verbitsky, M.; Blesa, J.; Jackson-Lewis, V.; Paredes, D.; Tillack, K.; Phani, S.; Kramer, E.; Przedborski, S.; Kottmann, A. Sonic Hedgehog Maintains Cellular and Neurochemical Homeostasis in the Adult Nigrostriatal Circuit. Neuron 2012, 75, 306–319.

- Gonzalez-Reyes, L.E.; Chiang, C.-C.; Zhang, M.; Johnson, J.; Arrillaga-Tamez, M.; Couturier, N.H.; Reddy, N.; Starikov, L.; Capadona, J.R.; Kottmann, A.H.; et al. Sonic Hedgehog is expressed by hilar mossy cells and regulates cellular survival and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17402–17420.

- Amankulor, N.M.; Hambardzumyan, D.; Pyonteck, S.M.; Becher, O.J.; Joyce, J.A.; Holland, E.C. Sonic hedgehog pathway activation is induced by acute brain injury and regulated by injury-related inflammation. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 10299–10308.

- Alvarez, J.I.; Dodelet-Devillers, A.; Kebir, H.; Ifergan, I.; Fabre, P.J.; Terouz, S.; Sabbagh, M.; Wosik, K.; Bourbonnière, L.; Bernard, M.; et al. The Hedgehog Pathway Promotes Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and CNS Immune Quiescence. Science 2011, 334, 1727–1731.

- Sirko, S.; Behrendt, G.; Johansson, P.; Tripathi, P.; Costa, M.; Bek, S.; Heinrich, C.; Tiedt, S.; Colak, D.; Dichgans, M.; et al. Reactive Glia in the Injured Brain Acquire Stem Cell Properties in Response to Sonic Hedgehog. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 426–439.

- Pitter, K.; Tamagno, I.; Feng, X.; Ghosal, K.; Amankulor, N.; Holland, E.C.; Hambardzumyan, D. The SHH/Gli pathway is reactivated in reactive glia and drives proliferation in response to neurodegeneration-induced lesions. Glia 2014, 62, 1595–1607.

- Cheng, F.Y.; Fleming, J.T.; Chiang, C. Bergmann glial Sonic hedgehog signaling activity is required for proper cerebellar cortical expansion and architecture. Dev. Biol. 2018, 440, 152–166.

- Priego, N.; Valiente, M. The potential of astrocytes as immune modulators in brain tumors. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1314.

- Zhang, G.; Rich, J.N. Reprogramming the microenvironment: Tricks of tumor-derived astrocytes. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 633–634.

- Gronseth, E.; Wang, L.; Harder, D.R.; Ramchandran, R. The Role of Astrocytes in Tumor Growth and Progression. In Astrocyte-Physiology and Pathology; IntechOpen: London, United Kingdom, 2018.

- Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; O’Brien, J.; Franco-Barraza, J.; Qi, X.; Yuan, H.; Jin, W.; Zhang, J.; Gu, C.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Necroptotic astrocytes contribute to maintaining stemness of disseminated medulloblastoma through CCL2 secretion. Neuro. Oncol. 2020, 22, 625–638.

- Cavalli, F.M.; Remke, M.; Rampasek, L.; Peacock, J.; Shih, D.J.H.; Luu, B.; Garzia, L.; Torchia, J.; Nor, C.; Morrissy, S.; et al. Intertumoral Heterogeneity within Medulloblastoma Subgroups. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 737–754.e6.

- Northcott, P.A.; Robinson, G.W.; Kratz, C.P.; Mabbott, D.J.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Clifford, S.C.; Rutkowski, S.; Ellison, D.W.; Malkin, D.; Taylor, M.; et al. Medulloblastoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 11.

- Wu, V.; Yeerna, H.; Nohata, N.; Chiou, J.; Harismendy, O.; Raimondi, F.; Inoue, A.; Russell, R.B.; Tamayo, P.; Gutkind, J.S. Illuminating the Onco-GPCRome: Novel G protein–coupled receptor-driven oncocrine networks and targets for cancer immunotherapy. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11062–11086.

- DI Pietro, C.; Marazziti, D.; Lasala, G.; Abbaszadeh, Z.; Golini, E.; Matteoni, R.; Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. Primary Cilia in the Murine Cerebellum and in Mutant Models of Medulloblastoma. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 37, 145–154.

- Marazziti, D.; Di Pietro, C.; Golini, E.; Mandillo, S.; Lasala, G.; Matteoni, R.; Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. Precocious cerebellum development and improved motor functions in mice lacking the astrocyte cilium-, patched 1-associated Gpr37l1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16486–16491.

- Han, Y.G.; Kim, H.J.; Dlugosz, A.A.; Ellison, D.W.; Gilbertson, R.J.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Dual and opposing roles of primary cilia in medulloblastoma development. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 1062–1065.

- Han, Y.G.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Role of primary cilia in brain development and cancer. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010, 20, 58–67.

- La Sala, G.; Di Pietro, C.; Matteoni, R.; Bolasco, G.; Marazziti, D.; Tocchini-Valentini, G.P. Gpr37l1/prosaposin receptor regulates Ptch1 trafficking, Shh production, and cell proliferation in cerebellar primary astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 2021, 99, 1064–1083, Epub ahead of print.

- Zurawel, R.H.; Allen, C.; Wechsler-Reya, R.; Scott, M.P.; Raffel, C. Evidence that haploinsufficiency of Ptch leads to medulloblastoma in mice. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2000, 28, 77–81.

- Mao, J.; Ligon, K.L.; Rakhlin, E.Y.; Thayer, S.P.; Bronson, R.T.; Rowitch, D.; McMahon, A.P. A novel somatic mouse model to survey tumorigenic potential applied to the Hedgehog pathway. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10171–10178.

- Snuderl, M.; Batista, A.; Kirkpatrick, N.D.; de Almodovar, C.R.; Riedemann, L.; Walsh, E.C.; Anolik, R.; Huang, Y.; Martin, J.; Kamoun, W.; et al. Targeting placental growth factor/neuropilin 1 pathway inhibits growth and spread of medulloblastoma. Cell 2013, 152, 1065–1076.