| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alessandro Beghini | + 2213 word(s) | 2213 | 2021-08-10 06:08:35 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 2213 | 2021-09-24 03:16:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the most common acute leukemia in adults, is a heterogeneous malignant clonal disorder arising from multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cells characterized by genetic and concerted epigenetic aberrations. Core binding factor-Leukemia (CBFL) is characterized by the recurrent reciprocal translocations t(8;21)(q22;q22) or inv(16)(p13;q22) that, expressing the distinctive RUNX1-RUNX1T1 (also known as Acute myeloid leukemia1-eight twenty-one, AML1-ETO or RUNX1/ETO) or CBFB-MYH11 (also known as CBFβ-SMMHC) translocation product respectively, disrupt the essential hematopoietic function of the CBF. In the past decade, remarkable progress has been achieved in understanding the structure, three-dimensional (3D) chromosomal topology, and disease-inducing genetic and epigenetic abnormalities of the fusion proteins that arise from disruption of the CBF subunit alpha and beta genes. Although CBFLs have a relatively good prognosis compared to other leukemia subtypes, 40–50% of patients still relapse, requiring intensive chemotherapy and allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation (alloHCT).

1. Introduction

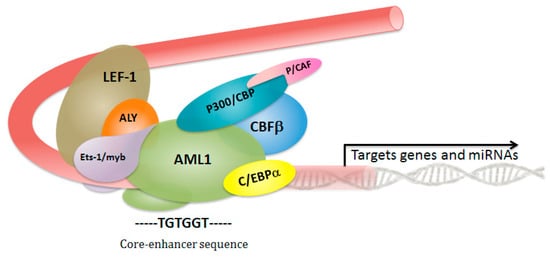

2. Core Binding Factor Complex: A Critical Role in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Fate

3. The Genomic Landscape of Core-Binding Factor Acute Myeloid Leukemias

References

- Miyoshi, H.; Shimizu, K.; Kozu, T.; Maseki, N.; Kaneko, Y.; Ohki, M. t(8;21) breakpoints on chromosome 21 in acute myeloid leukemia are clustered within a limited region of a single gene, AML1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 10431–10434.

- Link, K.A.; Chou, F.-S.; Mulloy, J.C. Core binding factor at the crossroads: Determining the fate of the HSC. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010, 222, 50–56.

- De Bruijn, M.; Dzierzak, E. Runx transcription factors in the development and function of the definitive hematopoietic system. Blood 2017, 129, 2061–2069.

- Menegatti, S.; de Kruijf, M.; Garcia-Alegria, E.; Lacaud, G.; Kouskoff, V. Transcriptional control of blood cell emergence. FEBS Lett. 2019.

- Liu, P.; Tarlé, S.A.; Hajra, A.; Claxton, D.F.; Marlton, P.; Freedman, M.; Siciliano, M.J.; Collins, F.S. Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia. Science 1993, 261, 1041–1044.

- Goyama, S.; Mulloy, J.C. Molecular pathogenesis of core binding factor leukemia: Current knowledge and future prospects. Int. J. Hematol. 2011, 94, 126–133.

- Sinha, C.; Cunningham, L.C.; Liu, P.P. Core Binding Factor Acute Myeloid Leukemia: New Prognostic Categories and Therapeutic Opportunities. Semin. Hematol. 2015, 52, 215–222.

- Schlenk, R.F.; Benner, A.; Krauter, J.; Büchner, T.; Sauerland, C.; Ehninger, G.; Schaich, M.; Mohr, B.; Niederwieser, D.; Krahl, R.; et al. Individual patient data-based meta-analysis of patients aged 16 to 60 years with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: A survey of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Intergroup. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 3741–3750.

- Jourdan, E.; Boissel, N.; Chevret, S.; Delabesse, E.; Renneville, A.; Cornillet, P.; Blanchet, O.; Cayuela, J.-M.; Recher, C.; Raffoux, E.; et al. Prospective evaluation of gene mutations and minimal residual disease in patients with core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013, 121, 2213–2223.

- Ghamari, A.; van de Corput, M.P.C.; Thongjuea, S.; van Cappellen, W.A.; van Ijcken, W.; van Haren, J.; Soler, E.; Eick, D.; Lenhard, B.; Grosveld, F.G. In vivo live imaging of RNA polymerase II transcription factories in primary cells. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 767–777.

- Ugarte, G.D.; Vargas, M.F.; Medina, M.A.; León, P.; Necuñir, D.; Elorza, A.A.; Gutiérrez, S.E.; Moon, R.T.; Loyola, A.; De Ferrari, G.V. Wnt signaling induces transcription, spatial proximity, and translocation of fusion gene partners in human hematopoietic cells. Blood 2015, 126, 1785–1789.

- Castilla, L.H.; Garrett, L.; Adya, N.; Orlic, D.; Dutra, A.; Anderson, S.; Owens, J.; Eckhaus, M.; Bodine, D.; Liu, P.P. The fusion gene Cbfb-MYH11 blocks myeloid differentiation and predisposes mice to acute myelomonocytic leukaemia. Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 144–146.

- Yuan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Miyamoto, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Harakawa, N.; Hetherington, C.J.; Burel, S.A.; Lagasse, E.; Weissman, I.L.; Akashi, K.; et al. AML1-ETO expression is directly involved in the development of acute myeloid leukemia in the presence of additional mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10398–10403.

- Faber, Z.J.; Chen, X.; Gedman, A.L.; Boggs, K.; Cheng, J.; Ma, J.; Radtke, I.; Chao, J.-R.; Walsh, M.P.; Song, G.; et al. The genomic landscape of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 1551–1556.

- Duployez, N.; Marceau-Renault, A.; Boissel, N.; Petit, A.; Bucci, M.; Geffroy, S.; Lapillonne, H.; Renneville, A.; Ragu, C.; Figeac, M.; et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016, 127, 2451–2459.

- Solh, M.; Yohe, S.; Weisdorf, D.; Ustun, C. Core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: Heterogeneity, monitoring, and therapy. Am. J. Hematol. 2014, 89, 1121–1131.

- Corces-Zimmerman, M.R.; Hong, W.-J.; Weissman, I.L.; Medeiros, B.C.; Majeti, R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2548–2553.

- Shima, T.; Miyamoto, T.; Kikushige, Y.; Yuda, J.; Tochigi, T.; Yoshimoto, G.; Kato, K.; Takenaka, K.; Iwasaki, H.; Mizuno, S.; et al. The ordered acquisition of Class II and Class I mutations directs formation of human t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia stem cell. Exp. Hematol. 2014, 42, 955–965.

- Nucifora, G.; Larson, R.A.; Rowley, J.D. Persistence of the 8;21 translocation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia type M2 in long-term remission. Blood 1993, 82, 712–715.

- Jurlander, J.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Ruutu, T.; Baer, M.R.; Strout, M.P.; Oberkircher, A.R.; Hoffmann, L.; Ball, E.D.; Frei-Lahr, D.A.; Christiansen, N.P.; et al. Persistence of the AML1/ETO fusion transcript in patients treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for t(8;21) leukemia. Blood 1996, 88, 2183–2191.

- Miyamoto, T.; Nagafuji, K.; Akashi, K.; Harada, M.; Kyo, T.; Akashi, T.; Takenaka, K.; Mizuno, S.; Gondo, H.; Okamura, T.; et al. Persistence of multipotent progenitors expressing AML1/ETO transcripts in long-term remission patients with t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood 1996, 87, 4789–4796.

- Croce, C.M.; Calin, G.A. miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell 2005, 122, 6–7.

- Fazi, F.; Rosa, A.; Fatica, A.; Gelmetti, V.; De Marchis, M.L.; Nervi, C.; Bozzoni, I. A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell 2005, 123, 819–831.

- Fischer, J.; Rossetti, S.; Datta, A.; Eng, K.; Beghini, A.; Sacchi, N.; Datta, A.; Eng, K.; Beghini, A.; Sacchi, N. miR-17 deregulates a core RUNX1-miRNA mechanism of CBF acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14.

- Pagano, F.; De Marinis, E.; Grignani, F.; Nervi, C. Epigenetic role of miRNAs in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. Epigenomics 2013, 5, 539–552.

- Fu, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, A.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, M.; Fu, H.; Xu, K.; Li, D.; Deng, A.; Zhang, Q.; et al. A minicircuitry of microRNA-9-1 and RUNX1-RUNX1T1 contributes to leukemogenesis in t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 653–661.

- Wallace, J.A.; O’Connell, R.M. MicroRNAs and acute myeloid leukemia: Therapeutic implications and emerging concepts. Blood 2017, 130, 1290–1301.

- Li, Y.; Ning, Q.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, M.; Gao, L.; Huang, W.; Jing, Y.; Huang, S.; Liu, A.; et al. A novel epigenetic AML1-ETO/THAP10/miR-383 mini-circuitry contributes to t(8;21) leukaemogenesis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017, 9, 933–949.

- Okuda, T.; van Deursen, J.; Hiebert, S.W.; Grosveld, G.; Downing, J.R. AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis. Cell 1996, 84, 321–330.

- Wang, Q.; Stacy, T.; Miller, J.D.; Lewis, A.F.; Gu, T.L.; Huang, X.; Bushweller, J.H.; Bories, J.C.; Alt, F.W.; Ryan, G.; et al. The CBFbeta subunit is essential for CBFalpha2 (AML1) function in vivo. Cell 1996, 87, 697–708.

- Niki, M.; Okada, H.; Takano, H.; Kuno, J.; Tani, K.; Hibino, H.; Asano, S.; Ito, Y.; Satake, M.; Noda, T. Hematopoiesis in the fetal liver is impaired by targeted mutagenesis of a gene encoding a non-DNA binding subunit of the transcription factor, polyomavirus enhancer binding protein 2/core binding factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 5697–5702.

- Ichikawa, M.; Asai, T.; Saito, T.; Seo, S.; Yamazaki, I.; Yamagata, T.; Mitani, K.; Chiba, S.; Ogawa, S.; Kurokawa, M.; et al. AML-1 is required for megakaryocytic maturation and lymphocytic differentiation, but not for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells in adult hematopoiesis. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 299–304.

- Growney, J.D.; Shigematsu, H.; Li, Z.; Lee, B.H.; Adelsperger, J.; Rowan, R.; Curley, D.P.; Kutok, J.L.; Akashi, K.; Williams, I.R.; et al. Loss of Runx1 perturbs adult hematopoiesis and is associated with a myeloproliferative phenotype. Blood 2005, 106, 494–504.

- Putz, G.; Rosner, A.; Nuesslein, I.; Schmitz, N.; Buchholz, F. AML1 deletion in adult mice causes splenomegaly and lymphomas. Oncogene 2006, 25, 929–939.

- Motoda, L.; Osato, M.; Yamashita, N.; Jacob, B.; Chen, L.Q.; Yanagida, M.; Ida, H.; Wee, H.-J.; Sun, A.X.; Taniuchi, I.; et al. Runx1 protects hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from oncogenic insult. Stem Cells 2007, 25, 2976–2986.

- Aikawa, Y.; Nguyen, L.A.; Isono, K.; Takakura, N.; Tagata, Y.; Schmitz, M.L.; Koseki, H.; Kitabayashi, I. Roles of HIPK1 and HIPK2 in AML1-and p300-dependent transcription, hematopoiesis and blood vessel formation. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3955–3965.

- Gu, T.L.; Goetz, T.L.; Graves, B.J.; Speck, N.A. Auto-inhibition and partner proteins, core-binding factor beta (CBFbeta) and Ets-1, modulate DNA binding by CBFalpha2 (AML1). Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 91–103.

- Tyner, J.W.; Tognon, C.E.; Bottomly, D.; Wilmot, B.; Kurtz, S.E.; Savage, S.L.; Long, N.; Schultz, A.R.; Traer, E.; Abel, M.; et al. Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 2018, 562, 526–531.

- Schoch, C.; Kohlmann, A.; Schnittger, S.; Brors, B.; Dugas, M.; Mergenthaler, S.; Kern, W.; Hiddemann, W.; Eils, R.; Haferlach, T. Acute myeloid leukemias with reciprocal rearrangements can be distinguished by specific gene expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10008–10013.

- Hsu, C.-H.; Nguyen, C.; Yan, C.; Ries, R.E.; Chen, Q.-R.; Hu, Y.; Ostronoff, F.; Stirewalt, D.L.; Komatsoulis, G.; Levy, S.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling of Pediatric Core Binding Factor AML. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138782.

- Cairoli, R.; Beghini, A.; Grillo, G.; Nadali, G.; Elice, F.; Ripamonti, C.B.; Colapietro, P.; Nichelatti, M.; Pezzetti, L.; Lunghi, M.; et al. Prognostic impact of c-KIT mutations in core binding factor leukemias: An Italian retrospective study. Blood 2006, 107, 3463–3468.

- Care, R.S.; Valk, P.J.M.; Goodeve, A.C.; Abu-Duhier, F.M.; Geertsma-Kleinekoort, W.M.C.; Wilson, G.A.; Gari, M.A.; Peake, I.R.; Löwenberg, B.; Reilly, J.T. Incidence and prognosis of c-KIT and FLT3 mutations in core binding factor (CBF) acute myeloid leukaemias. Br. J. Haematol. 2003, 121, 775–777.

- Beghini, A.; Ripamonti, C.B.; Cairoli, R.; Cazzaniga, G.; Colapietro, P.; Elice, F.; Nadali, G.; Grillo, G.; Haas, O.A.; Biondi, A.; et al. KIT activating mutations: Incidence in adult and pediatric acute myeloid leukemia, and identification of an internal tandem duplication. Haematologica 2004, 89, 920–925.

- Schnittger, S.; Kohl, T.M.; Haferlach, T.; Kern, W.; Hiddemann, W.; Spiekermann, K.; Schoch, C. KIT-D816 mutations in AML1-ETO-positive AML are associated with impaired event-free and overall survival. Blood 2006, 107, 1791–1799.

- Cairoli, R.; Grillo, G.; Beghini, A.; Tedeschi, A.; Ripamonti, C.B.; Larizza, L.; Morra, E. C-Kit point mutations in core binding factor leukemias: Correlation with white blood cell count and the white blood cell index. Leukemia 2003, 17, 471–472.

- Ustun, C.; Morgan, E.; Moodie, E.E.M.; Pullarkat, S.; Yeung, C.; Broesby-Olsen, S.; Ohgami, R.; Kim, Y.; Sperr, W.; Vestergaard, H.; et al. Core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21): Risk factors and a novel scoring system (I-CBFit). Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 4447–4455.

- . Madan, V.; Han, L.; Hattori, N.; Teoh, W.W.; Mayakonda, A.; Sun, Q.Y.; Ding, L.W.; Nordin, H.B.M.; Lim, S.L.; Shyamsunder, P.; et al. ASXL2 regulates hematopoiesis in mice and its deficiency promotes myeloid expansion. Haematologica. 2018, 103, 1980–1990.

- Martinez-Soria, N.; McKenzie, L.; Draper, J.; Ptasinska, A.; Issa, H.; Poltluri, S.; Blair, H.J.; Pickin, A.; Isa, A.; Chin, P.S.; et al. The Oncogenic Transcription Factor RUNX1/ETO Corrupts Cell Cycle Regulation to Drive Leukemic Transformation. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 626–642.

- Mazumdar, C.; Shen, Y.; Xavy, S.; Zhao, F.; Reinisch, A.; Li, R.; Corces, M.R.; Flynn, R.A.; Buenrostro, J.D.; Chan, S.M.; et al. Leukemia-Associated Cohesin Mutants Dominantly Enforce Stem Cell Programs and Impair Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 675–688.

- Kawashima, N.; Akashi, A.; Nagata, Y.; Kihara, R.; Ishikawa, Y.; Asou, N.; Ohtake, S.; Miyawaki, S.; Sakura, T.; Ozawa, Y.; et al. Clinical significance of ASXL2 and ZBTB7A mutations and C-terminally truncated RUNX1-RUNX1T1 expression in AML patients with t(8;21) enrolled in the JALSG AML201 study. Ann. Hematol. 2019, 98, 83–91.

- Abdel-Wahab, O.; Gao, J.; Adli, M.; Dey, A.; Trimarchi, T.; Chung, Y.R.; Kuscu, C.; Hricik, T.; Ndiaye-Lobry, D.; Lafave, L.M.; et al. Deletion of Asxl1 results in myelodysplasia and severe developmental defects in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2641–2659.

- Inoue, D.; Kitaura, J.; Togami, K.; Nishimura, K.; Enomoto, Y.; Uchida, T.; Kagiyama, Y.; Kawabata, K.C.; Nakahara, F.; Izawa, K.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndromes are induced by histone methylation–altering ASXL1 mutations. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 4627–4640.

- Micol, J.-B.; Duployez, N.; Boissel, N.; Petit, A.; Geffroy, S.; Nibourel, O.; Lacombe, C.; Lapillonne, H.; Etancelin, P.; Figeac, M.; et al. Frequent ASXL2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1 chromosomal translocations. Blood 2014, 124, 1445–1449.

- Jones, D.; Yao, H.; Romans, A.; Dando, C.; Pierce, S.; Borthakur, G.; Hamilton, A.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Ravandi, F.; Garcia-Manero, G.; et al. Modeling interactions between leukemia-specific chromosomal changes, somatic mutations, and gene expression patterns during progression of core-binding factor leukemias. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2010, 49, 182–191.

- Chou, W.-C.; Huang, H.-H.; Hou, H.-A.; Chen, C.-Y.; Tang, J.-L.; Yao, M.; Tsay, W.; Ko, B.-S.; Wu, S.-J.; Huang, S.-Y.; et al. Distinct clinical and biological features of de novo acute myeloid leukemia with additional sex comb-like 1 (ASXL1) mutations. Blood 2010, 116, 4086–4094.

- Thota, S.; Viny, A.D.; Makishima, H.; Spitzer, B.; Radivoyevitch, T.; Przychodzen, B.; Sekeres, M.A.; Levine, R.L.; Maciejewski, J.P. Genetic alterations of the cohesin complex genes in myeloid malignancies. Blood 2014, 124, 1790–1798.

- Johansson, B.; Mertens, F.; Mitelman, F. Secondary chromosomal abnormalities in acute leukemias. Leukemia 1994, 8, 953–962.

- Nishii, K.; Usui, E.; Katayama, N.; Lorenzo, F.; Nakase, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Miwa, H.; Mizutani, M.; Tanaka, I.; Nasu, K.; et al. Characteristics of t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with additional chromosomal abnormality: Concomitant trisomy 4 may constitute a distinctive subtype of t(8;21) AML. Leukemia 2003, 17, 731–737.

- Kuchenbauer, F.; Schnittger, S.; Look, T.; Gilliland, G.; Tenen, D.; Haferlach, T.; Hiddemann, W.; Buske, C.; Schoch, C. Identification of additional cytogenetic and molecular genetic abnormalities in acute myeloid leukaemia with t(8;21)/AML1-ETO. Br. J. Haematol. 2006, 134, 616–619.

- Beghini, A.; Peterlongo, P.; Ripamonti, C.B.; Larizza, L.; Cairoli, R.; Morra, E.; Mecucci, C. C-kit mutations in core binding factor leukemias. Blood 2000, 95, 726–727.

- Beghini, A.; Magnani, I.; Ripamonti, C.B.; Larizza, L. Amplification of a novel c-Kit activating mutation Asn(822)-Lys in the Kasumi-1 cell line: A t(8;21)-Kit mutant model for acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol. J. 2002, 3, 157–163.

- Matsuura, S.; Yan, M.; Lo, M.-C.; Ahn, E.-Y.; Weng, S.; Dangoor, D.; Matin, M.; Higashi, T.; Feng, G.-S.; Zhang, D.-E. Negative effects of GM-CSF signaling in a murine model of t(8;21)-induced leukemia. Blood 2012, 119, 3155–3163.

- Klug, C.A. GM-CSFRα: The sex-chromosome link to t(8;21)(+) AML? Blood 2012, 119, 2976–2977.

- Krauth, M.-T.; Eder, C.; Alpermann, T.; Bacher, U.; Nadarajah, N.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, C.; Haferlach, T.; Schnittger, S. High number of additional genetic lesions in acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)/RUNX1-RUNX1T1: Frequency and impact on clinical outcome. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1449–1458.