Chlorella vulgaris biomass means the biomass made of Chlorella vulgaris, which is a kind of microalgae. Under appropriate conditions, microalgae convert solar energy into chemical energy stored as starch or lipids, which are precursors for bioethanol and biodiesel production. Given the higher photosynthetic efficiency, higher biomass production per unit area and faster growth rate compared to energy crops, microalgae are good alternative as feedstock for biofuel production. An additional advantage of microalgae is the lack of competition for nutrients with food crops. Furthermore, biomass production can be located on marginal lands. The negative environmental impact associated with the cultivation of microalgae for energy purposes is described as potentially negligible.

1. Introduction

The main source of energy in the world, also used for fuel production, is still crude oil

[1]. Limited fossil fuel resources and adverse environmental impact due to greenhouse gas emissions increased interest in advanced fuel production technologies

[2]. The primary feedstocks used for their production are obtained from energy crops or lignocellulosic wastes. Less conventional sources include the biomass of macroalgae and microalgae

[3][4].

Microalgae are unicellular or multicellular simple organisms that are metabolically diverse, but most of them are photoautotrophs

[5]. A valuable property of theirs is that their fast biomass growth, which per hectare is several times higher compared to terrestrial plants

[6], but just like plants, microalgae require nutrients, light and carbon dioxide to grow

[7].

The main problems of algal biofuel production are related to cultivation costs and biomass dehydration processes

[8][9]. To increase the cost-effectiveness of biomass production, nutrients contained in municipal wastewater

[10][11] or in aquaculture wastewater

[12], are used in cultivation. Microalgae have a high ability to remove nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, thus biomass production can be more sustainable and can be used in the bioremediation of the aquatic environment

[13].

Commercial cultivation of microalgae requires the supply of significant amounts of inorganic carbon for photosynthesis

[14]. This is mainly provided by carbon dioxide from the air and eventually from industrial emissions

[15]. This may be a method for its biological sequestration

[16], especially considering that some microalgae are capable of assimilating up to 1.83 Mg of CO

2 during the production of 1 Mg of their biomass

[17]. Higher CO

2 concentration promotes lipid accumulation in the cells

[18]. Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration depends on anthropogenic activities

[19] and industrial development stage

[20] and may increase above 400 PPM

[21]. Concentrations of CO

2 may be an important factor to limit growth and development of some microalgal species

[22], however, minimum and maximum concentrations CO

2 dissolved in the culture medium for microalgae cultivation vary from one species to another

[23]. Some microalgae can grow under atmospheric air

[24], others in extremely high CO

2 concentrations ranging from 40 to 100 vol%

[25]. Compressed CO

2 can also be used in cultivation

[26], but this increases the costs, which are related to the capture, compression, transport or storage of this gas

[27]. The cost of using compressed carbon dioxide in microalgae culture can account for up to half of the total cost of biomass production

[28]. An alternative option may be using of bicarbonate salts

[29]. These compounds have much higher solubility in water than CO

2 and higher efficiency in biomass production compared to compressed carbon dioxide

[22]. A review of the recent progress in bicarbonate-based microalgae cultivation suggested potential to significantly reduce production cost. The use of sodium bicarbonate reduces the cost of carbon supply, increases the accumulation of valuable components, and is energetically efficient

[30]. New technologies make it possible to produce sodium bicarbonate from carbon dioxide, including from industrial CO

2 emissions, which are responsible for the negative effects of climate change

[31].

2. Utilisation of CO2 from Sodium Bicarbonate to Produce Chlorella vulgaris Biomass in Tubular Photobioreactors for Biofuel Purposes

2.1. Biomass Production with CO2 from Sodium Bicarbonate

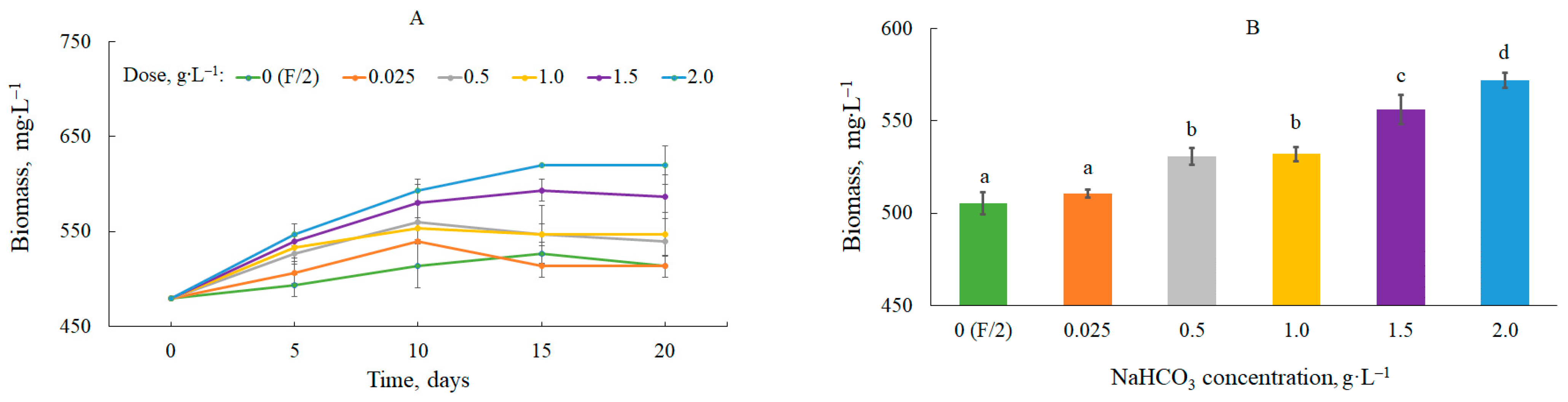

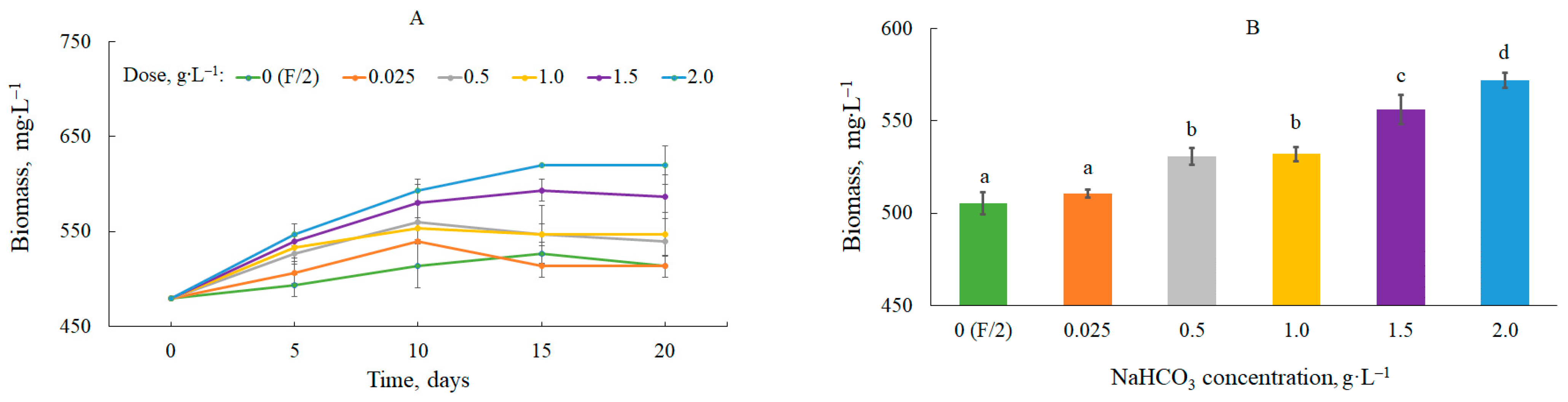

The effect of the NaHCO3 dose on the growth dynamics of C. vulgaris is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in biomass content (A) and average biomass content in the culture (B). Mean over each column not marked with the same letter is significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in biomass content (A) and average biomass content in the culture (B). Mean over each column not marked with the same letter is significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

The biomass productivity changed as a function of the bicarbonate dose and time (

Table 1). The highest values were observed at the beginning of the study at a dose of 2.0 g∙L

–1 (13.3 ± 2.3 mg∙L

–1·d

–1). The productivity decreased with time. The changes could be due to the time-limited availability of nutrients as observed in batch cultures

[32] or to the level of carbon dioxide utilisation.

Table 1. Biomass productivity in relation to bicarbonate dose.

| Level of Sodium Bicarbonate (g∙L–1) |

Biomass Productivity (mg·L–1·d–1) |

| Day 5 |

Day 10 |

Day 15 |

Day 20 |

| 0 (F/2) |

2.7 ± 2.3 |

3.3 ± 2.3 |

3.1 ± 0.8 |

1.7 ± 0.6 |

| 0.025 |

5.3 ± 2.3 |

6.0 ± 0.0 |

2.2 ± 0.8 |

1.7 ± 0.6 |

| 0.5 |

9.3 ± 2.3 |

8.0 ± 2.0 |

4.4 ± 0.8 |

3.0 ± 0.0 |

| 1.0 |

10.7 ± 2.3 |

7.3 ± 1.2 |

4.4 ± 2.0 |

3.3 ± 1.2 |

| 1.5 |

12.0 ± 0.0 |

10.0 ± 2.0 |

7.6 ± 0.8 |

5.3 ± 1.2 |

| 2.0 |

13.3 ± 2.3 |

11.3 ± 1.2 |

9.3 ± 0.0 |

7.0 ± 1.0 |

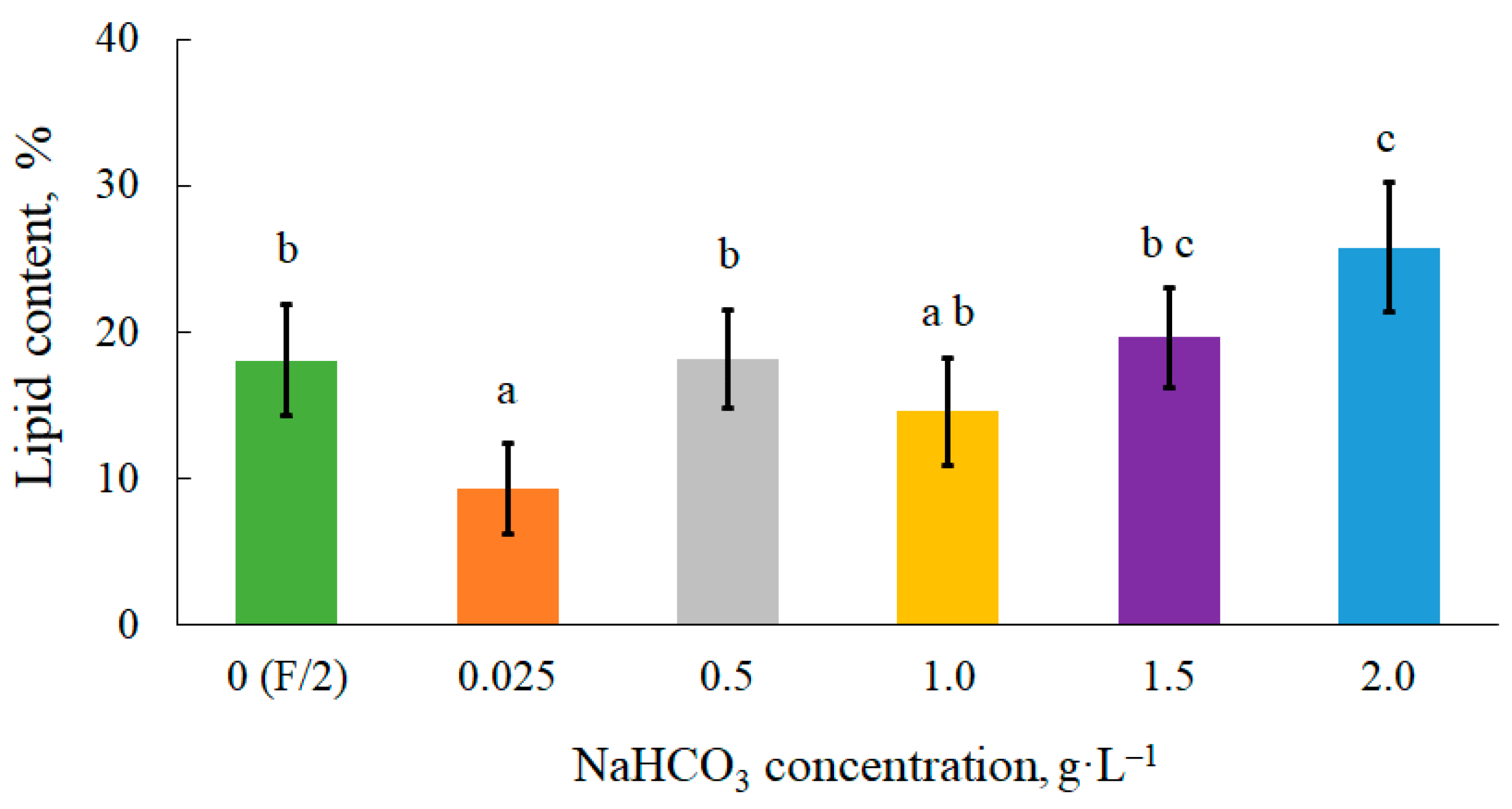

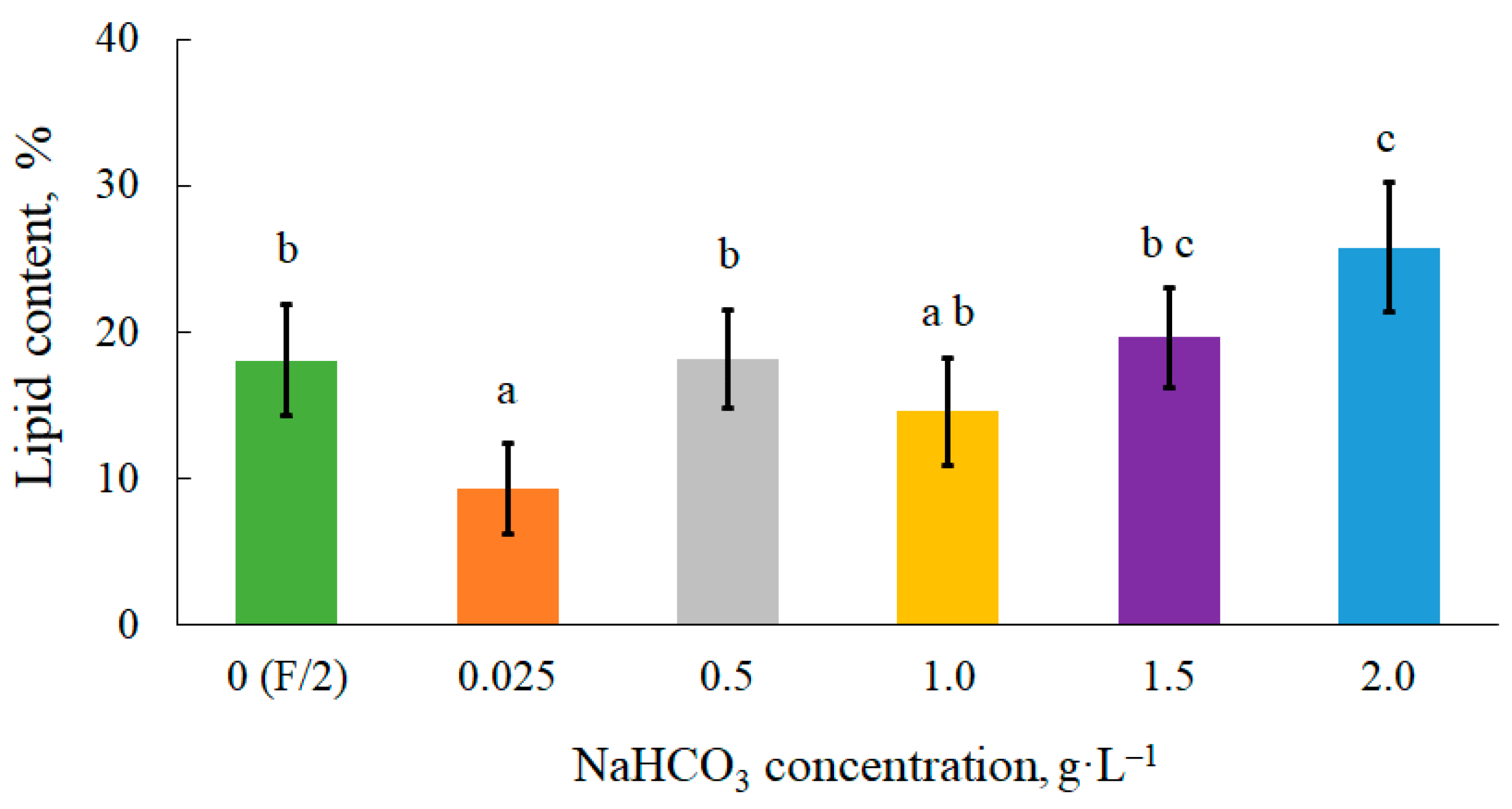

3.2. Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate on Lipid Accumulation in Microalgal Biomass

The presence of bicarbonate in the culture medium, in excess of carbon storage in algal cells, can promote lipid accumulation

[33]. According to

Figure 2, adding low concentrations of bicarbonate from 0.5 g∙L

–1 to 1.5 g∙L

–1 had no distinct effect on the lipid production of

C. vulgaris. From own research indicate that lipid synthesis in cells requires a higher dose of inorganic carbon in the medium. In the present study, a significant increase in lipids in the presence of NaHCO

3, compared to the control 0 (F/2) object, was observed in the culture at a highest dose of 2.0 g∙L

–1. The lipid content was 26 ± 4% and this was 8% higher than the values obtained without bicarbonate. Li et al.

[34] observed an increase in lipid content in

C.vulgaris cells with increasing NaHCO

3 dose, but a decrease in the amount of biomass. At a dose of 160 mM the authors obtained approx. 450 mg∙g

–1 of lipids. A linear dose-dependent increase in lipid content of algal biomass was reported by Bywaters and Fritsen

[35]. A too-high concentration of NaHCO

3 may adversely affect lipid accumulation in microalgae cells. Significantly reduced lipid accumulation capacity in

C. pyrenoidosa biomass, after introduction of 200 mM NaHCO

3, was observed by Sampathkumar and Gothandam

[36]. This is also confirmed by Pimolrat et al.

[37], who analyzed the effect of NaHCO

3 at doses ranging from 0.05 to 5 g∙L

−1 on the stimulation of triacylglycerol production in

Chaetoceros gracilis cells.

Figure 2. Lipid content in microalgal biomass. Mean over each column not marked with the same letter is significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

2.3. Carbon Content and CO2 Fixation Rate in Microalgal Biomass

The carbon content in microalgal biomass ranged from 0.832 ± 0.127 g∙dw

–1 in control 0 (F/2) object to 1.322 0.062 g∙dw

–1 at a dose 2.0 g∙L

–1 NaHCO

3. With increasing carbon in biomass, there was an increase in CO

2 fixation, which in the study ranged from 0.139 ± 0.047 g·L

−1·d

−1 to 0.925 ± 0.073 g·L

−1·d

−1. A high carbon content and rate of fixation indicate a high potential for CO

2 sequestration in

C. vulgaris biomass

[38]. Similar results were reported by Prabakaran and Ravindran

[39], who cultured three different algae strains (

Chlorella sp.,

Ulothrix sp. and

Chlorococcum sp.) and obtained the highest carbon content and CO

2 fixation rate for

Chlorella sp. at 0.486 g∙dw

–1 and 0.68 g∙mL

−1d

−1, respectively. Some authors indicate a linear relationship between NaHCO

3 dose and carbon accumulation in algal biomass

[33][34]. Mokashi et al.

[40] applied bicarbonate in

C. vulgaris cultures at dose from 0.25 to 1 g∙L

−1 and determined the highest carbon content and CO

2 fixation rate of 0.497 g∙dw

–1 and 0.69 g∙mL

–1d

–1, respectively, at the highest dose. The level of carbon dioxide fixation varies depending on the microalgae strain and the carbon source (

Table 2). The efficiency of the process carried out at the technical scale was higher compared to the results obtained by other authors, regardless of whether sodium bicarbonate or carbon dioxide was used in the microalgae cultivation.

Table 2. CO2 fixation of microalgae biomass.

| Strain |

Carbon Source and Dose |

Experimental Scale |

CO2 Fixation, g·L–1·d–1 |

References |

| Chlorella vulgaris |

NaHCO3, 2.0 g·L−1 |

100 L |

0.93 |

This study |

| Chlorella vulgaris |

NaHCO3, 1.0 g·L−1 |

100 mL |

0.69 |

[40] |

| Chlorella sp. |

NaHCO3, 7.5 g·L−1 |

500 mL |

0.21 |

[41] |

| Scenedesmus obliquus |

CO2, 10% |

1 L |

0.26 |

[42] |

| Scenedesmus almeriensis |

CO2, 3% |

28.5 L |

0.24 |

[43] |

The optical density used to determine biomass growth does not always correlate with actual biomass content

[44]; however, in the presented study, there was a significant and positive correlation between these parameters (r = 0.863) and moreover between the amount of biomass and the carbon content of microalgae cells (r = 0.785), as well as CO

2 fixation rate (r = 0.806).

3. Conclusions

We confirmed that the addition of NaHCO3 to culture medium provides effective carbon source and facilitates cell growth and C. vulgaris biomass production. The highest biomass content (572 ± 4 mg·L−1) and productivity (7.0 ± 1.0 mg·L−1·d−1) were obtained with bicarbonate at a dose of 2.0 g·L−1. Under these conditions, the average optical density in culture was also the highest (OD680 0.181 ± 0.00). An increase in NaHCO3 dose increased lipid accumulation, carbon content in microalgae cells and carbon dioxide fixation rate. The highest values were observed at the highest dose of NaHCO3. The average lipid content of the biomass was 26 ± 4%. The carbon content of the biomass increased to 1.322 ± 0.062 g∙dw−1, while the rate of CO2 fixation increased to 0.925 ± 0.073 g·L−1·d−1. There was a positive correlation between the biomass amount and the optical density and between the biomass, the carbon content and the CO2 fixation rate.

The experiments were carried out in photobioreactors used in the industrial production of microalgae biomass and therefore the results obtained showed the real values that are possible to achieve at this scale. The lipid content in the biomass increased with the increasing dose of sodium bicarbonate. Future research should focus on determining the maximum dose of NaHCO3 for optimal microalgal growth. It is important for the economic sustainability of microalgae cultivation for fuel purposes. The commercial production of microalgae biomass is carried out as a semi-continuous or continuous culture, so the correlation between the NaHCO3 dose and the overaccumulation of Na+ ions and the possibility of limiting microalgal growth should be verified.

Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in biomass content (A) and average biomass content in the culture (B). Mean over each column not marked with the same letter is significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in biomass content (A) and average biomass content in the culture (B). Mean over each column not marked with the same letter is significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.