| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Florence Carrouel | + 2449 word(s) | 2449 | 2021-07-15 08:08:36 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2449 | 2021-08-26 05:18:41 | | |

Video Upload Options

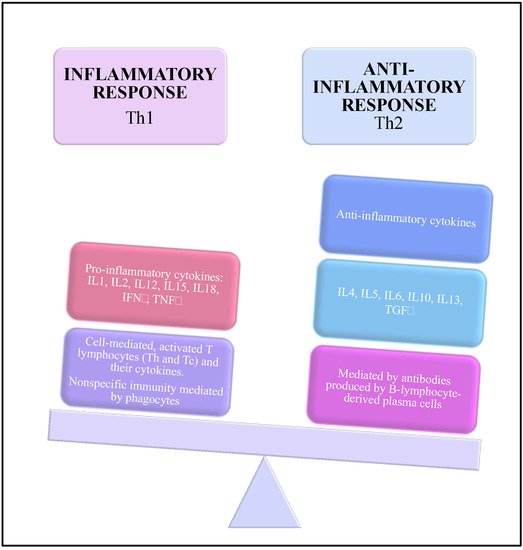

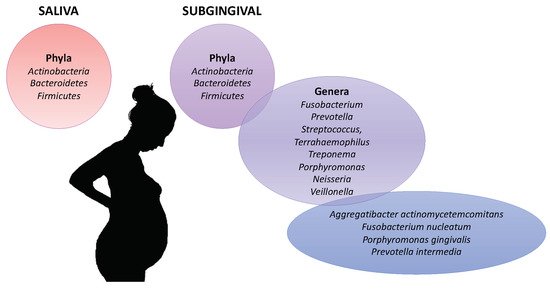

Pre-eclampsia, the second most frequent direct source of maternal mortality, is a multisystem gestational disorder characterized by proteinuria and maternal hypertension after the 20th gestational week. Metabolic conditions, immunological changes, and fluctuating hormone levels of the pregnant woman induce a dysbiosis of the oral microbiota and contribute to increase inflammation of periodontal tissues. Periodontal pathogens, as well as inflammatory molecules produced in response to periodontopathogens, could diffuse through the bloodstream inducing a placenta inflammatory response. In addition, periodontopathogens can colonize the vaginal microbiota through the gastrointestinal tract or during oro-genital contact. A cumulative bi-directional relationship between periodontal conditions, pathogens and pre-eclampsia exists.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy causes significant unique changes in maternal immune responses and metabolism, yet it is unclear whether/how these alterations may be connected to infections [1]. There is however, strong and solid scientific evidence that pregnancy can induce bacterial dysbiosis, especially in the vaginal and gut microbiome, leading to metabolic alterations and complications in the mother and the newborn [1][2][3]. Hypertension is the most frequent health complication in pregnancy, affecting 10% of pregnancies worldwide [4]. Classification of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are classified into 4 categories including pre-eclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension and pre-eclampsia-eclampsia [5].

Pre-eclampsia is the second most frequent direct source of maternal mortality, causing an average of 500,000 fetal and neonatal deaths and an estimated of 76,000 direct maternal deaths and each year [6]. Although the causes of pre-eclampsia are still discussed, research has suggested that the placenta has a central place in the pathogenesis of this disease. Evidence supports that fetuses and neonates of preeclamptic women are especially impacted by the maternal condition, independently of uteroplacental restriction of flow [7]. Pre-eclampsia is considered to be an endothelial disturbance where the oxidative pathophysiological stress and disturbance of lipid status have potential implications in the development of pre-eclampsia among high-risk pregnancies [8].

2. Hormonal Oral, Immunological and Oral Microbiota Changes and Their Impact on Periodontal Disease during the Pregnancy

3. Periodontal Pathogens and Pre-Eclampsia

4. Conclusions

References

- Amir, M.; Brown, J.A.; Rager, S.L.; Sanidad, K.Z.; Ananthanarayanan, A.; Zeng, M.Y. Maternal Microbiome and Infections in Pregnancy. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1996.

- Edwards, S.M.; Cunningham, S.A.; Dunlop, A.L.; Corwin, E.J. The Maternal Gut Microbiome during Pregnancy. Mcn Am. J. Matern. Child. Nurs 2017, 42, 310–317.

- Prince, A.L.; Chu, D.M.; Seferovic, M.D.; Antony, K.M.; Ma, J.; Aagaard, K.M. The Perinatal Microbiome and Pregnancy: Moving Beyond the Vaginal Microbiome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5.

- Magee, L.A.; von Dadelszen, P. State-of-the-Art Diagnosis and Treatment of Hypertension in Pregnancy. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1664–1677.

- ACOG. Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obs. Gynecol. 2019, 133, 1.

- Magee, L.A.; Sharma, S.; Nathan, H.L.; Adetoro, O.O.; Bellad, M.B.; Goudar, S.; Macuacua, S.E.; Mallapur, A.; Qureshi, R.; Sevene, E.; et al. The Incidence of Pregnancy Hypertension in India, Pakistan, Mozambique, and Nigeria: A Prospective Population-Level Analysis. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002783.

- Braunthal, S.; Brateanu, A. Hypertension in Pregnancy: Pathophysiology and Treatment. Sage Open Med. 2019, 7.

- McElwain, C.J.; Tuboly, E.; McCarthy, F.P.; McCarthy, C.M. Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in Pre-Eclampsia and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Windows into Future Cardiometabolic Health? Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2020, 11.

- Lain, K.Y.; Catalano, P.M. Metabolic Changes in Pregnancy. Clin. Obs. Gynecol. 2007, 50, 938–948.

- Wang, Q.; Würtz, P.; Auro, K.; Mäkinen, V.-P.; Kangas, A.J.; Soininen, P.; Tiainen, M.; Tynkkynen, T.; Jokelainen, J.; Santalahti, K.; et al. Metabolic Profiling of Pregnancy: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Evidence. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 205.

- Machado, F.C.; Cesar, D.E.; Assis, A.V.D.A.; Diniz, C.G.; Ribeiro, R.A. Detection and Enumeration of Periodontopathogenic Bacteria in Subgingival Biofilm of Pregnant Women. Braz. Oral Res. 2012, 26, 443–449.

- de Souza Massoni, R.S.; Aranha, A.M.F.; Matos, F.Z.; Guedes, O.A.; Borges, Á.H.; Miotto, M.; Porto, A.N. Correlation of Periodontal and Microbiological Evaluations, with Serum Levels of Estradiol and Progesterone, during Different Trimesters of Gestation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11762.

- Gürsoy, M.; Gürsoy, U.K.; Liukkonen, A.; Kauko, T.; Penkkala, S.; Könönen, E. Salivary Antimicrobial Defensins in Pregnancy. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 807–815.

- Preshaw, P.M. Oral Contraceptives and the Periodontium. Periodontology 2013, 61, 125–159.

- Tang, Z.-R.; Zhang, R.; Lian, Z.-X.; Deng, S.-L.; Yu, K. Estrogen-Receptor Expression and Function in Female Reproductive Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 1123.

- Zheng, Y.; Murphy, L.C. Regulation of Steroid Hormone Receptors and Coregulators during the Cell Cycle Highlights Potential Novel Function in Addition to Roles as Transcription Factors. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2016, 14, e001.

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.-W.; Su, W.-L.; Zhu, H.-Y.; Ouyang, S.-Y.; Cao, Y.-T.; Jiang, S.-Y. Sex Hormones Enhance Gingival Inflammation without Affecting IL-1β and TNF-α in Periodontally Healthy Women during Pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016.

- Saadaoui, M.; Singh, P.; Al Khodor, S. Oral Microbiome and Pregnancy: A Bidirectional Relationship. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 145, 103293.

- Abu-Raya, B.; Michalski, C.; Sadarangani, M.; Lavoie, P.M. Maternal Immunological Adaptation during Normal Pregnancy. Front. Immunol 2020, 11, 575197.

- Markou, E.; Eleana, B.; Lazaros, T.; Antonios, K. The Influence of Sex Steroid Hormones on Gingiva of Women. Open Dent. J. 2009, 3, 114–119.

- Carbonne, B.; Dallot, E.; Haddad, B.; Ferré, F.; Cabrol, D. Effects of Progesterone on Prostaglandin E(2)-Induced Changes in Glycosaminoglycan Synthesis by Human Cervical Fibroblasts in Culture. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2000, 6, 661–664.

- Jafri, Z.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sawai, M.; Sultan, N. Influence of Female Sex Hormones on Periodontium: A Case Series. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2015, 6, S146–149.

- Mascarenhas, P.; Gapski, R.; Al-Shammari, K.; Wang, H.-L. Influence of Sex Hormones on the Periodontium. J. Clin. Periodontol 2003, 30, 671–681.

- Wu, M.; Chen, S.-W.; Jiang, S.-Y. Relationship between Gingival Inflammation and Pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 623427.

- Mor, G.; Aldo, P.; Alvero, A.B. The Unique Immunological and Microbial Aspects of Pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 469–482.

- Challis, J.R.; Lockwood, C.J.; Myatt, L.; Norman, J.E.; Strauss, J.F.; Petraglia, F. Inflammation and Pregnancy. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 206–215.

- Yang, I.; Knight, A.K.; Dunlop, A.L.; Corwin, E.J. Characterizing the Subgingival Microbiome of Pregnant African American Women. J. Obs. Gynecol Neonatal. Nurs. 2019, 48, 140–152.

- Zoller, A.L.; Kersh, G.J. Estrogen Induces Thymic Atrophy by Eliminating Early Thymic Progenitors and Inhibiting Proliferation of Beta-Selected Thymocytes. J. Immunol 2006, 176, 7371–7378.

- Kanda, N.; Tamaki, K. Estrogen Enhances Immunoglobulin Production by Human PBMCs. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 282–288.

- Figuero, E.; Carrillo-de-Albornoz, A.; Martín, C.; Tobías, A.; Herrera, D. Effect of Pregnancy on Gingival Inflammation in Systemically Healthy Women: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 457–473.

- Gürsoy, M.; Zeidán-Chuliá, F.; Könönen, E.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Liukkonen, J.; Sorsa, T.; Gürsoy, U.K. Pregnancy-Induced Gingivitis and OMICS in Dentistry: In Silico Modeling and in Vivo Prospective Validation of Estradiol-Modulated Inflammatory Biomarkers. OMICS 2014, 18, 582–590.

- Borgo, P.V.; Rodrigues, V.A.A.; Feitosa, A.C.R.; Xavier, K.C.B.; Avila-Campos, M.J. Association between Periodontal Condition and Subgingival Microbiota in Women during Pregnancy: A Longitudinal Study. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2014, 22, 528–533.

- Nuriel-Ohayon, M.; Neuman, H.; Koren, O. Microbial Changes during Pregnancy, Birth, and Infancy. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1031.

- Fujiwara, N.; Tsuruda, K.; Iwamoto, Y.; Kato, F.; Odaki, T.; Yamane, N.; Hori, Y.; Harashima, Y.; Sakoda, A.; Tagaya, A.; et al. Significant Increase of Oral Bacteria in the Early Pregnancy Period in Japanese Women. J. Investig Clin. Dent. 2017, 8.

- Lin, W.; Jiang, W.; Hu, X.; Gao, L.; Ai, D.; Pan, H.; Niu, C.; Yuan, K.; Zhou, X.; Xu, C.; et al. Ecological Shifts of Supragingival Microbiota in Association with Pregnancy. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol 2018, 8.

- Balan, P.; Chong, Y.S.; Umashankar, S.; Swarup, S.; Loke, W.M.; Lopez, V.; He, H.G.; Seneviratne, C.J. Keystone Species in Pregnancy Gingivitis: A Snapshot of Oral Microbiome during Pregnancy and Postpartum Period. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9.

- DiGiulio, D.B.; Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Costello, E.K.; Lyell, D.J.; Robaczewska, A.; Sun, C.L.; Goltsman, D.S.A.; Wong, R.J.; Shaw, G.; et al. Temporal and Spatial Variation of the Human Microbiota during Pregnancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11060–11065.

- Cobb, C.M.; Kelly, P.J.; Williams, K.B.; Babbar, S.; Angolkar, M.; Derman, R.J. The Oral Microbiome and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Int. J. Womens Health 2017, 9, 551–559.

- Tellapragada, C.; Eshwara, V.K.; Acharya, S.; Bhat, P.; Kamath, A.; Vishwanath, S.; Mukhopadhyay, C. Prevalence of Clinical Periodontitis and Putative Periodontal Pathogens among South Indian Pregnant Women. Int. J. Microbiol. 2014, 2014, 420149.

- Abusleme, L.; Dupuy, A.K.; Dutzan, N.; Silva, N.; Burleson, J.A.; Strausbaugh, L.D.; Gamonal, J.; Diaz, P.I. The Subgingival Microbiome in Health and Periodontitis and Its Relationship with Community Biomass and Inflammation. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1016–1025.

- Wei, B.-J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Yu, L.; Wu, B. Periodontal Disease and Risk of Preeclampsia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70901.

- Fischer, L.A.; Demerath, E.; Bittner-Eddy, P.; Costalonga, M. Placental Colonization with Periodontal Pathogens: The Potential Missing Link. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 383–392.e3.

- Konopka, T.; Zakrzewska, A. Periodontitis and Risk for Preeclampsia - a Systematic Review. Ginekol. Pol. 2020, 91, 158–164.

- Daalderop, L.A.; Wieland, B.V.; Tomsin, K.; Reyes, L.; Kramer, B.W.; Vanterpool, S.F.; Been, J.V. Periodontal Disease and Pregnancy Outcomes: Overview of Systematic Reviews. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2018, 3, 10–27.

- Matevosyan, N.R. Periodontal Disease and Perinatal Outcomes. Arch. Gynecol Obs. 2011, 283, 675–686.

- Sgolastra, F.; Petrucci, A.; Severino, M.; Gatto, R.; Monaco, A. Relationship between Periodontitis and Pre-Eclampsia: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71387.

- Desai, K.; Desai, P.; Duseja, S.; Kumar, S.; Mahendra, J.; Duseja, S. Significance of Maternal Periodontal Health in Preeclampsia. J. Int Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 103–107.

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hua, L.; Zhang, D.; Hu, T.; Ge, Z.-L. Maternal Periodontal Disease and Risk of Preeclampsia: A Meta-Analysis. J. Huazhong Univ Sci Technol. Med. Sci 2014, 34, 729–735.

- Bourgeois, D.; Inquimbert, C.; Ottolenghi, L.; Carrouel, F. Periodontal Pathogens as Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Diseases, Diabetes, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Cancer, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Is There Cause for Consideration? Microorganisms 2019, 7, 424.

- Popova, C.; Dosseva-Panova, V.; Panov, V. Microbiology of Periodontal Diseases. A Review. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2013, 27, 3754–3759.

- Fox, R.; Kitt, J.; Leeson, P.; Aye, C.Y.L.; Lewandowski, A.J. Preeclampsia: Risk Factors, Diagnosis, Management, and the Cardiovascular Impact on the Offspring. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1625.

- Beckers, K.F.; Sones, J.L. Maternal Microbiome and the Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy, Preeclampsia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1–H10.

- Aagaard, K.; Ma, J.; Antony, K.M.; Ganu, R.; Petrosino, J.; Versalovic, J. The Placenta Harbors a Unique Microbiome. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 237ra65.

- Amarasekara, R.; Jayasekara, R.W.; Senanayake, H.; Dissanayake, V.H.W. Microbiome of the Placenta in Pre-Eclampsia Supports the Role of Bacteria in the Multifactorial Cause of Pre-Eclampsia. J. Obs. Gynaecol. Res. 2015, 41, 662–669.

- Barak, S.; Oettinger-Barak, O.; Machtei, E.E.; Sprecher, H.; Ohel, G. Evidence of Periopathogenic Microorganisms in Placentas of Women with Preeclampsia. J. Periodontol. 2007, 78, 670–676.

- Han, Y.W. Oral Health and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes—What’s Next? J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 289–293.

- Andrukhov, O.; Ulm, C.; Reischl, H.; Nguyen, P.Q.; Matejka, M.; Rausch-Fan, X. Serum Cytokine Levels in Periodontitis Patients in Relation to the Bacterial Load. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 885–892.

- Parthiban, P.S.; Mahendra, J.; Logaranjani, A.; Shanmugam, S.; Balakrishnan, A.; Junaid, M.; Namasivayam, A. Association between Specific Periodontal Pathogens, Toll-like Receptor-4, and Nuclear Factor-ΚB Expression in Placental Tissues of Pre-Eclamptic Women with Periodontitis. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9.

- Cleys, E.R.; Halleran, J.L.; Enriquez, V.A.; da Silveira, J.C.; West, R.C.; Winger, Q.A.; Anthony, R.V.; Bruemmer, J.E.; Clay, C.M.; Bouma, G.J. Androgen Receptor and Histone Lysine Demethylases in Ovine Placenta. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117472.

- Soory, M. Bacterial Steroidogenesis by Periodontal Pathogens and the Effect of Bacterial Enzymes on Steroid Conversions by Human Gingival Fibroblasts in Culture. J. Periodontal Res. 1995, 30, 124–131.

- Khong, Y.; Brosens, I. Defective Deep Placentation. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2011, 25, 301–311.

- Brosens, I.; Pijnenborg, R.; Vercruysse, L.; Romero, R. The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” Are Associated with Disorders of Deep Placentation. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol 2011, 204, 193–201.

- Vigliani, M.B.; Bakardjiev, A.I. Intracellular Organisms as Placental Invaders. Fetal. Matern. Med. Rev. 2014, 25, 332–338.

- Chaparro, A.; Blanlot, C.; Ramírez, V.; Sanz, A.; Quintero, A.; Inostroza, C.; Bittner, M.; Navarro, M.; Illanes, S.E. Porphyromonas Gingivalis, Treponema Denticola and Toll-like Receptor 2 Are Associated with Hypertensive Disorders in Placental Tissue: A Case-Control Study. J. Periodontal Res. 2013, 48, 802–809.

- Swati, P.; Ambika Devi, K.; Thomas, B.; Vahab, S.A.; Kapaettu, S.; Kushtagi, P. Simultaneous Detection of Periodontal Pathogens in Subgingival Plaque and Placenta of Women with Hypertension in Pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol Obs. 2012, 285, 613–619.

- Vanterpool, S.F.; Been, J.V.; Houben, M.L.; Nikkels, P.G.J.; De Krijger, R.R.; Zimmermann, L.J.I.; Kramer, B.W.; Progulske-Fox, A.; Reyes, L. Porphyromonas Gingivalis within Placental Villous Mesenchyme and Umbilical Cord Stroma Is Associated with Adverse Pregnancy Outcome. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146157.

- Reyes, L.; Phillips, P.; Wolfe, B.; Golos, T.G.; Walkenhorst, M.; Progulske-Fox, A.; Brown, M. Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome. J. Oral Microbiol. 2018, 10, 1374153.

- Golic, M.; Haase, N.; Herse, F.; Wehner, A.; Vercruysse, L.; Pijnenborg, R.; Balogh, A.; Saether, P.C.; Dissen, E.; Luft, F.C.; et al. Natural Killer Cell Reduction and Uteroplacental Vasculopathy. Hypertension 2016, 68, 964–973.

- Tavarna, T.; Phillips, P.L.; Wu, X.-J.; Reyes, L. Fetal Growth Restriction Is a Host Specific Response to Infection with an Impaired Spiral Artery Remodeling-Inducing Strain of Porphyromonas Gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14606.