| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dario Brunetti | + 2303 word(s) | 2303 | 2021-07-19 03:34:16 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 2282 | 2021-08-05 11:15:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

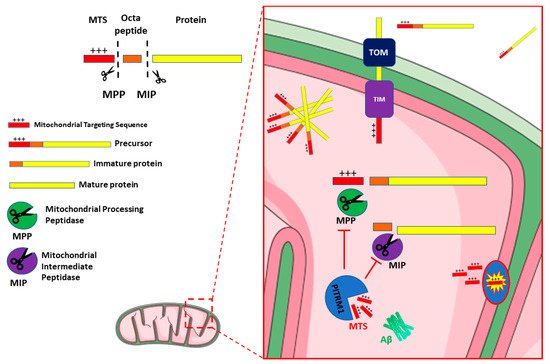

Mounting evidence shows a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer Disease. Increased oxidative stress, defective mitodynamics, and impaired oxidative phosphorylation leading to decreased ATP production, can determine synaptic dysfunction, apoptosis, and neurodegeneration. Furthermore, mitochondrial proteostasis and the protease-mediated quality control system, carrying out degradation of potentially toxic peptides and misfolded or damaged proteins inside mitochondria, are emerging as potential pathogenetic mechanisms. The enzyme pitrilysin metallopeptidase 1 (PITRM1) is a key player in these processes; it is responsible for degrading mitochondrial targeting sequences that are cleaved off from the imported precursor proteins and for digesting a mitochondrial fraction of amyloid beta (Aβ).

1. Introduction

2. PITRM1/PreP

3. PITRM1/PreP and Alzheimer’s Disease

3.1. PITRM1/PreP Is Downregulated in AD Patients and Mouse Models

3.2. Targeting PITRM1/PreP as a New Therapeutic Strategy for Treatment of AD

References

- Morán, M.; Moreno-Lastres, D.; Marín-Buera, L.; Arenas, J.; Martín, M.A.; Ugalde, C. Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Dysfunction: Implications in Neurodegeneration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 595–609.

- Monzio Compagnoni, G.; Di Fonzo, A.; Corti, S.; Comi, G.P.; Bresolin, N.; Masliah, E. The Role of Mitochondria in Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Lesson from Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2020, 57, 2959–2980.

- Wu, Y.; Chen, M.; Jiang, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Drug Targets via Apoptotic Signaling. Mitochondrion 2019, 49, 35–45.

- Tapias, V. Editorial: Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1372.

- Mosconi, L.; Pupi, A.; De Leon, M.J. Brain Glucose Hypometabolism and Oxidative Stress in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 180–195.

- Bifari, F.; Dolci, S.; Bottani, E.; Pino, A.; Di Chio, M.; Zorzin, S.; Ragni, M.; Zamfir, R.G.; Brunetti, D.; Bardelli, D.; et al. Complete Neural Stem Cell (NSC) Neuronal Differentiation Requires a Branched Chain Amino Acids-Induced Persistent Metabolic Shift towards Energy Metabolism. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 158, 104863.

- Son, G.; Han, J. Roles of Mitochondria in Neuronal Development. BMB Rep. 2018, 51, 549–556.

- Inak, G.; Rybak-Wolf, A.; Lisowski, P.; Pentimalli, T.M.; Jüttner, R.; Glažar, P.; Uppal, K.; Bottani, E.; Brunetti, D.; Secker, C.; et al. Defective Metabolic Programming Impairs Early Neuronal Morphogenesis in Neural Cultures and an Organoid Model of Leigh Syndrome. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1929.

- Winklhofer, K.F.; Haass, C. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2010, 1802, 29–44.

- Sharma, A.; Behl, T.; Sharma, L.; Aelya, L.; Bungau, S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Opportunities. CDT 2021, 22.

- Carinci, M.; Vezzani, B.; Patergnani, S.; Ludewig, P.; Lessmann, K.; Magnus, T.; Casetta, I.; Pugliatti, M.; Pinton, P.; Giorgi, C. Different Roles of Mitochondria in Cell Death and Inflammation: Focusing on Mitochondrial Quality Control in Ischemic Stroke and Reperfusion. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 169.

- Mehta, A.R.; Gregory, J.M.; Dando, O.; Carter, R.N.; Burr, K.; Nanda, J.; Story, D.; McDade, K.; Smith, C.; Morton, N.M.; et al. Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Deficits in C9orf72 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Motor Neurons Cause Dysfunctional Axonal Homeostasis. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 257–279.

- Gohel, D.; Berguerand, N.C.; Tassone, F.; Singh, R. The Emerging Molecular Mechanisms for Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in FXTAS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165918.

- Spano, M. The Possible Involvement of Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review. Funct. Neurol. 2015, 30, 151–158.

- Huang, C.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Z. Maintaining the Balance of TDP-43, Mitochondria, and Autophagy: A Promising Therapeutic Strategy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 40.

- Moreira, P.I.; Carvalho, C.; Zhu, X.; Smith, M.A.; Perry, G. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is a Trigger of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2010, 1802, 2–10.

- Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Cascades in Alzheimer’s Disease. JAD 2018, 62, 1403–1416.

- Hansson Petersen, C.A.; Alikhani, N.; Behbahani, H.; Wiehager, B.; Pavlov, P.F.; Alafuzoff, I.; Leinonen, V.; Ito, A.; Winblad, B.; Glaser, E.; et al. The Amyloid -Peptide Is Imported into Mitochondria via the TOM Import Machinery and Localized to Mitochondrial Cristae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13145–13150.

- Pagani, L.; Eckert, A. Amyloid-Beta Interaction with Mitochondria. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2011, 2011, 1–12.

- Lustbader, J.W.; Cirilli, M.; Lin, C.; Xu, H.W.; Takuma, K.; Wang, N.; Caspersen, C.; Chen, X.; Pollak, S.; Chaney, M.; et al. ABAD Directly Links Abeta to Mitochondrial Toxicity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science 2004, 304, 448–452.

- Manczak, M.; Calkins, M.J.; Reddy, P.H. Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics and Abnormal Interaction of Amyloid Beta with Mitochondrial Protein Drp1 in Neurons from Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: Implications for Neuronal Damage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 2495–2509.

- Yao, J.; Irwin, R.W.; Zhao, L.; Nilsen, J.; Hamilton, R.T.; Brinton, R.D. Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Deficit Precedes Alzheimer’s Pathology in Female Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14670–14675.

- Rhein, V.; Song, X.; Wiesner, A.; Ittner, L.M.; Baysang, G.; Meier, F.; Ozmen, L.; Bluethmann, H.; Drose, S.; Brandt, U.; et al. Amyloid- and Tau Synergistically Impair the Oxidative Phosphorylation System in Triple Transgenic Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20057–20062.

- Morais, V.A.; De Strooper, B. Mitochondria Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Disorders: Cause or Consequence. JAD 2010, 20, S255–S263.

- Selfridge, J.E.; Lezi, E.; Lu, J.; Swerdlow, R.H. Role of Mitochondrial Homeostasis and Dynamics in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 51, 3–12.

- Pinho, C.M.; Teixeira, P.F.; Glaser, E. Mitochondrial Import and Degradation of Amyloid-β Peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 1069–1074.

- Swerdlow, R.H.; Khan, S.M. A “Mitochondrial Cascade Hypothesis” for Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease. Med. Hypotheses 2004, 63, 8–20.

- Rugarli, E.I.; Langer, T. Mitochondrial Quality Control: A Matter of Life and Death for Neurons: Mitochondrial Quality Control and Neurodegeneration. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1336–1349.

- Schmidt, O.; Pfanner, N.; Meisinger, C. Mitochondrial Protein Import: From Proteomics to Functional Mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 655–667.

- Bolender, N.; Sickmann, A.; Wagner, R.; Meisinger, C.; Pfanner, N. Multiple Pathways for Sorting Mitochondrial Precursor Proteins. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 42–49.

- Hawlitschek, G.; Schneider, H.; Schmidt, B.; Tropschug, M.; Hartl, F.-U.; Neupert, W. Mitochondrial Protein Import: Identification of Processing Peptidase and of PEP, a Processing Enhancing Protein. Cell 1988, 53, 795–806.

- Yang, M.J.; Geli, V.; Oppliger, W.; Suda, K.; James, P.; Schatz, G. The MAS-Encoded Processing Protease of Yeast Mitochondria. Interaction of the Purified Enzyme with Signal Peptides and a Purified Precursor Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 6416–6423.

- Vögtle, F.-N.; Wortelkamp, S.; Zahedi, R.P.; Becker, D.; Leidhold, C.; Gevaert, K.; Kellermann, J.; Voos, W.; Sickmann, A.; Pfanner, N.; et al. Global Analysis of the Mitochondrial N-Proteome Identifies a Processing Peptidase Critical for Protein Stability. Cell 2009, 139, 428–439.

- Vögtle, F.-N.; Prinz, C.; Kellermann, J.; Lottspeich, F.; Pfanner, N.; Meisinger, C. Mitochondrial Protein Turnover: Role of the Precursor Intermediate Peptidase Oct1 in Protein Stabilization. MBoC 2011, 22, 2135–2143.

- Mossmann, D.; Meisinger, C.; Vögtle, F.-N. Processing of Mitochondrial Presequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Regul. Mech. 2012, 1819, 1098–1106.

- Teixeira, P.F.; Glaser, E. Processing Peptidases in Mitochondria and Chloroplasts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 360–370.

- Kücükköse, C.; Taskin, A.A.; Marada, A.; Brummer, T.; Dennerlein, S.; Vögtle, F. Functional Coupling of Presequence Processing and Degradation in Human Mitochondria. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 600–613.

- Ståhl, A.; Nilsson, S.; Lundberg, P.; Bhushan, S.; Biverståhl, H.; Moberg, P.; Morisset, M.; Vener, A.; Mäler, L.; Langel, U.; et al. Two Novel Targeting Peptide Degrading Proteases, PrePs, in Mitochondria and Chloroplasts, so Similar and Still Different. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 349, 847–860.

- Kambacheld, M.; Augustin, S.; Tatsuta, T.; Müller, S.; Langer, T. Role of the Novel Metallopeptidase MoP112 and Saccharolysin for the Complete Degradation of Proteins Residing in Different Subcompartments of Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20132–20139.

- Taylor, A.B.; Smith, B.S.; Kitada, S.; Kojima, K.; Miyaura, H.; Otwinowski, Z.; Ito, A.; Deisenhofer, J. Crystal Structures of Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase Reveal the Mode for Specific Cleavage of Import Signal Sequences. Structure 2001, 9, 615–625.

- Mzhavia, N.; Berman, Y.L.; Qian, Y.; Yan, L.; Devi, L.A. Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of Human Metalloprotease 1: A Novel Member of the Pitrilysin Family of Metalloendoproteases. DNA Cell Biol. 1999, 18, 369–380.

- King, J.V.; Liang, W.G.; Scherpelz, K.P.; Schilling, A.B.; Meredith, S.C.; Tang, W.-J. Molecular Basis of Substrate Recognition and Degradation by Human Presequence Protease. Structure 2014, 22, 996–1007.

- Falkevall, A.; Alikhani, N.; Bhushan, S.; Pavlov, P.F.; Busch, K.; Johnson, K.A.; Eneqvist, T.; Tjernberg, L.; Ankarcrona, M.; Glaser, E. Degradation of the Amyloid β-Protein by the Novel Mitochondrial Peptidasome, PreP. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29096–29104.

- Johnson, K.A.; Bhushan, S.; Ståhl, A.; Hallberg, B.M.; Frohn, A.; Glaser, E.; Eneqvist, T. The Closed Structure of Presequence Protease PreP Forms a Unique 10 000 Å3 Chamber for Proteolysis. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 1977–1986.

- Taskin, A.A.; Kücükköse, C.; Burger, N.; Mossmann, D.; Meisinger, C.; Vögtle, F.-N. The Novel Mitochondrial Matrix Protease Ste23 Is Required for Efficient Presequence Degradation and Processing. MBoC 2017, 28, 997–1002.

- Im, H.; Manolopoulou, M.; Malito, E.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Neant-Fery, M.; Sun, C.-Y.; Meredith, S.C.; Sisodia, S.S.; Leissring, M.A.; et al. Structure of Substrate-Free Human Insulin-Degrading Enzyme (IDE) and Biophysical Analysis of ATP-Induced Conformational Switch of IDE. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 25453–25463.

- Björk, B.F.; Katzov, H.; Kehoe, P.; Fratiglioni, L.; Winblad, B.; Prince, J.A.; Graff, C. Positive Association between Risk for Late-Onset Alzheimer Disease and Genetic Variation in IDE. Neurobiol. Aging 2007, 28, 1374–1380.

- González-Casimiro, C.M.; Merino, B.; Casanueva-Álvarez, E.; Postigo-Casado, T.; Cámara-Torres, P.; Fernández-Díaz, C.M.; Leissring, M.A.; Cózar-Castellano, I.; Perdomo, G. Modulation of Insulin Sensitivity by Insulin-Degrading Enzyme. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 86.

- Alikhani, N.; Guo, L.; Yan, S.; Du, H.; Pinho, C.M.; Chen, J.X.; Glaser, E.; Yan, S.S. Decreased Proteolytic Activity of the Mitochondrial Amyloid-β Degrading Enzyme, PreP Peptidasome, in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Mitochondria. JAD 2011, 27, 75–87.

- Sekar, S.; McDonald, J.; Cuyugan, L.; Aldrich, J.; Kurdoglu, A.; Adkins, J.; Serrano, G.; Beach, T.G.; Craig, D.W.; Valla, J.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Is Associated with Altered Expression of Genes Involved in Immune Response and Mitochondrial Processes in Astrocytes. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 583–591.

- Begcevic, I.; Kosanam, H.; Martínez-Morillo, E.; Dimitromanolakis, A.; Diamandis, P.; Kuzmanov, U.; Hazrati, L.-N.; Diamandis, E.P. Semiquantitative Proteomic Analysis of Human Hippocampal Tissues from Alzheimer’s Disease and Age-Matched Control Brains. Clin. Proteom. 2013, 10, 5.

- Niedzielska, E.; Smaga, I.; Gawlik, M.; Moniczewski, A.; Stankowicz, P.; Pera, J.; Filip, M. Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 4094–4125.

- Chen, J.; Teixeira, P.F.; Glaser, E.; Levine, R.L. Mechanism of Oxidative Inactivation of Human Presequence Protease by Hydrogen Peroxide. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 77, 57–63.

- Kierdorf, K.; Fritz, G. RAGE Regulation and Signaling in Inflammation and Beyond. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 55–68.

- Sparvero, L.J.; Asafu-Adjei, D.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Amin, N.; Im, J.; Rutledge, R.; Lin, B.; Amoscato, A.A.; Zeh, H.J.; et al. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts), RAGE Ligands, and Their Role in Cancer and Inflammation. J. Transl. Med. 2009, 7, 17.

- Fang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Du, H.; Yan, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhong, C.; Wu, L.; Vangavaragu, J.R.; Yan, S.; et al. Increased Neuronal PreP Activity Reduces Aβ Accumulation, Attenuates Neuroinflammation and Improves Mitochondrial and Synaptic Function in Alzheimer Disease’s Mouse Model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 5198–5210.

- Xu, Y.-J.; Mei, Y.; Qu, Z.-L.; Zhang, S.-J.; Zhao, W.; Fang, J.-S.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Liu, S.-J.; Fang, Y.-Q.; et al. Ligustilide Ameliorates Memory Deficiency in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice via Restoring Mitochondrial Dysfunction. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–15.

- Brunetti, D.; Bottani, E.; Segala, A.; Marchet, S.; Rossi, F.; Orlando, F.; Malavolta, M.; Carruba, M.O.; Lamperti, C.; Provinciali, M.; et al. Targeting Multiple Mitochondrial Processes by a Metabolic Modulator Prevents Sarcopenia and Cognitive Decline in SAMP8 Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1171.

- Morley, J.E.; Armbrecht, H.J.; Farr, S.A.; Kumar, V.B. The Senescence Accelerated Mouse (SAMP8) as a Model for Oxidative Stress and Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2012, 1822, 650–656.

- Du, F.; Yu, Q.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Z.; Vangavaragu, J.R.; Chen, D.; Yan, S.F.; Yan, S.S. Gain of PITRM1 Peptidase in Cortical Neurons Affords Protection of Mitochondrial and Synaptic Function in an Advanced Age Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Aging Cell 2021, 20.

- Vangavaragu, J.R.; Valasani, K.R.; Gan, X.; Yan, S.S. Identification of Human Presequence Protease (HPreP) Agonists for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 506–516.

- Li, N.-S.; Liang, W.; Piccirilli, J.A.; Tang, W.-J. Reinvestigating the Synthesis and Efficacy of Small Benzimidazole Derivatives as Presequence Protease Enhancers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 184, 111746.