| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ibrahim Tarbiyyah | + 4074 word(s) | 4074 | 2021-07-27 03:52:58 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 4053 | 2021-07-28 03:07:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

Global development has generated a plethora of unfavorable and adverse environmental factors for the living organisms in the ecosystem. Plants are sessile organisms, and they are crucial to sustain life on earth. Since plants are sessile, they face a great number of environmental challenges related to abiotic stresses, such as temperature fluctuation, drought, salinity, flood and metal contamination. Salinity and drought are considered major abiotic stresses that negatively affect the plants’ growth and production of useful content. However, plants have evolved various molecular mechanisms to increase their tolerance to these environmental stresses. There is a whole complex system of communication (cross-talk) through massive signaling cascades that are activated and modulated in response to salinity and drought. Secondary metabolites are believed to play significant roles in the plant’s response and resistance to salinity and drought stress. Until recently, attempts to unravel the biosynthetic pathways were limited mainly due to the inadequate plant genomics resources. However, recent advancements in generating high-throughput “omics” datasets, computational tools and functional genomics approach integration have aided in the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways of many plant bioactive metabolites.

1. Introduction

2. Generic Pathways for Plant Response to Abiotic Stresses

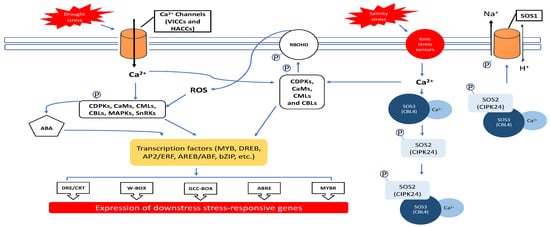

2.1. Ca2+ and ROS Regulation during Salinity and Drought Exposure

2.2. Ca2+ Ions

2.3. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

3. Phytohormonal Regulation in Salinity and Water Deficit Stresses

3.1. Abscisic Acid

3.2. Ethylene

3.3. Jasmonic Acid and MeJA

4. Transcriptional Regulation during Salinity and Drought Stresses

4.1. AP2/EREBP

4.2. MYB

4.3. Basic Helix–Loop–Helix (bHLH)

References

- Mittler, R.; Blumwald, E. Genetic Engineering for Modern Agriculture: Challenges and Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 443–462.

- Hodges, D.M.; Lester, G.E.; Munro, K.D.; Toivonen, P. Oxidative Stress: Importance for Postharvest Quality. HortScience 2004, 39, 924–929.

- Crisosto, C.H.; Johnson, R.S.; Luza, J.G.; Crisosto, G.M. Irrigation Regimes Affect Fruit Soluble Solids Concentration and Rate of Water Loss of ‘O’Henry’ Peaches. HortScience 1994, 29, 1169–1171.

- You, J.; Chan, Z. ROS Regulation During Abiotic Stress Responses in Crop Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1092.

- Landi, S.; Hausman, J.-F.; Guerriero, G.; Esposito, S. Poaceae vs. Abiotic Stress: Focus on Drought and Salt Stress, Recent Insights and Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1214.

- Patra, B.; Schluttenhofer, C.; Wu, Y.; Pattanaik, S.; Yuan, L. Transcriptional regulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2013, 1829, 1236–1247.

- Kapazoglou, A.; Tsaftaris, A. Epigenetic Chromatin Regulators as Mediators of Abiotic Stress Responses in Cereals. In Abiotic Stress in Plants—Mechanisms and Adaptations; Available online: (accessed on 19 July 2021).

- Jain, M.; Nagar, P.; Goel, P.; Singh, A.K.; Kumari, S.; Mustafiz, A. Second Messengers: Central Regulators in Plant Abiotic Stress Response. In Abiotic Stress-Mediated Sensing and Signaling in Plants: An Omics Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 47–94.

- Tiwari, S.; Lata, C.; Chauhan, P.S.; Prasad, V.; Prasad, M. A Functional Genomic Perspective on Drought Signalling and its Crosstalk with Phytohormone-mediated Signalling Pathways in Plants. Curr. Genom. 2017, 18, 469–482.

- Kumari, S.; Panigrahi, K.C.S. Light and auxin signaling cross-talk programme root development in plants. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 26.

- Mazid, M.; Khan, T.A.; Mohammad, F. Effect of abiotic stress on synthesis of secondary plant products: A critical review. Agric. Rev. 2011, 32, 172–182.

- Akula, R.; Ravishankar, G.A. Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1720–1731.

- Edreva, A.; Velikova, V.; Tsonev, T.; Dagnon, S.; Gesheva, E. Stress-Protective Role of Secondary Metabolites: Diversity of Functions and Mechanisms. Gen. Appl. Plant Physiol. 2008, 34, 67–78.

- Khan, A.L.; Hussain, J.; Hamayun, M.; Gilani, S.A.; Ahmad, S.; Rehman, G.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kang, S.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Secondary Metabolites from Inula britannica L. and Their Biological Activities. Molecules 2010, 15, 1562–1577.

- Macías-Rubalcava, M.L.; Fernández, R.E.S. Secondary metabolites of endophytic Xylaria species with potential applications in medicine and agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 15.

- Ivănescu, B.; Burlec, A.; Crivoi, F.; Rosu, C.; Corciovă, A. Secondary Metabolites from Artemisia Genus as Biopesticides. Molecules 2021, 26, 3061.

- Rafińska, K.; Pomastowski, P.; Wrona, O.; Górecki, R.; Buszewski, B. Medicago sativa as a source of secondary metabolites for agriculture and pharmaceutical industry. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 20, 520–539.

- Jennings, D.W.; Deutsch, H.M.; Zalkow, L.H.; Teja, A.S. Supercritical extraction of taxol from the bark of Taxus brevifolia. J. Supercrit. Fluids 1992, 5, 1–6.

- Hussein, R.A.; El-Anssary, A.A. Plants Secondary Metabolites: The Key Drivers of the Pharmacological Actions of Medicinal Plants. Herb. Med. 2019.

- Bettaieb, I.; Hamrouni, I.; Bourgou, S.; Limam, F.; Marzouk, B. Drought effects on polyphenol composition and antioxidant activities in aerial parts of Salvia officinalis L. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 1103–1111.

- Shen, Q.; Lu, X.; Yan, T.; Fu, X.; Lv, Z.; Zhang, F.; Pan, Q.; Wang, G.; Sun, X.; Tang, K. The jasmonate-responsive Aa MYC 2 transcription factor positively regulates artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1269–1281.

- Twilley, D.; Rademan, S.; Lall, N. A review on traditionally used South African medicinal plants, their secondary mtaolites and their potential development into anticancer agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 261, 113101.

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Shao, H.; Tang, X. Recent Advances in Utilizing Transcription Factors to Improve Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance by Transgenic Technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 67.

- Fedrizzi, L.; Lim, D.; Carafoli, E. Calcium and signal transduction. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2008, 36, 175–180.

- Miller, G.; Shulaev, V.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen signaling and abiotic stress. Physiol. Plant. 2008, 133, 481–489.

- Singh, R.; Parihar, P.; Singh, S.; Mishra, R.K.; Singh, V.P.; Prasad, S.M. Reactive oxygen species signaling and stomatal movement: Current updates and future perspectives. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 213–218.

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: An overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 307–321.

- Bouaziz, D.; Pirrello, J.; Charfeddine, M.; Hammami, A.; Jbir, R.; Dhieb, A.; Bouzayen, M.; Gargouri-Bouzid, R. Overexpression of StDREB1 Transcription Factor Increases Tolerance to Salt in Transgenic Potato Plants. Mol. Biotechnol. 2012, 54, 803–817.

- Matsui, A.; Ishida, J.; Morosawa, T.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kaminuma, E.; Endo, T.A.; Okamoto, M.; Nambara, E.; Nakajima, M.; Kawashima, M.; et al. Arabidopsis Transcriptome Analysis under Drought, Cold, High-Salinity and ABA Treatment Conditions using a Tiling Array. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1135–1149.

- Ciarmiello, L.F.; Woodrow, P.; Fuggi, A.; Pontecorvo, G.; Carillo, P. Plant Genes for Abiotic Stress. In Abiotic Stress in Plants—Mechanisms and Adaptations; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011.

- Feno, S.; Butera, G.; Vecellio Reane, D.; Rizzuto, R.; Raffaello, A. Crosstalk between Calcium and ROS in Pathophysiological Conditions. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9324018.

- Köster, P.; Wallrad, L.; Edel, K.H.; Faisal, M.; Alatar, A.A.; Kudla, J. The Battle of Two Ions: Ca2+ Signalling against Na+ Stress. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 39–48.

- Huang, F.; Luo, J.; Ning, T.; Cao, W.; Jin, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, S. Cytosolic and Nucleosolic Calcium Signaling in Response to Osmotic and Salt Stresses Are Independent of Each Other in Roots of Arabidopsis Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1648.

- Quintero, F.J.; Ohta, M.; Shi, H.; Zhu, J.-K.; Pardo, J.M. Reconstitution in Yeast of the Arabidopsis SOS Signaling Pathway for Na+ Homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 9061–9066.

- Goel, P.; Bhuria, M.; Sinha, R.; Sharma, T.R.; Singh, A.K. Promising Transcription Factors for Salt and Drought Tolerance in Plants. In Molecular Approaches in Plant Biology and Environmental Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 7–50.

- Guan, B.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F. Molecular Characterization and Functional Analysis of a Vacuolar Na+/H+ Antiporter Gene (HcNHX1) from Halostachys Caspica. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 1889–1899.

- Osakabe, Y.; Arinaga, N.; Umezawa, T.; Katsura, S.; Nagamachi, K.; Tanaka, H.; Ohiraki, H.; Yamada, K.; Seo, S.U.; Abo, M.; et al. Osmotic Stress Responses and Plant Growth Controlled by Potassium Transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 609–624.

- Yang, L.; Liu, H.; Fu, S.M.; Ge, H.M.; Tang, R.J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.H.; Zhang, H.X. Na+/H+ and K+/H+ Antiporters AtNHX1 and AtNHX3 from Arabidopsis Improve Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Poplar. Biol. Plant. 2017, 61, 641–650.

- Liu, Y.; He, C. Regulation of Plant Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Stress Responses: Learning from AtRBOHD. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 995–1007.

- Shkryl, Y.N.; Veremeichik, G.N.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Zhuravlev, Y.N. Induction of Anthraquinone Biosynthesis in Rubia Cordifolia Cells by Heterologous Expression of a Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase Gene. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 1734–1738.

- Allwood, E.G.; Davies, D.R.; Gerrish, C.; Ellis, B.E.; Bolwell, G.P. Phosphorylation of Phenylalanine Ammonia-lyase: Evidence for a Novel Protein Kinase and Identification of the Phosphorylated Residue. Febs Lett. 1999, 457, 47–52.

- Demidchik, V.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of Cytosolic Calcium Elevation in Plants: The Role of Ion Channels, Calcium Extrusion Systems and NADPH Oxidase-Mediated “ROS-Ca2+ Hub. ” Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 9–27.

- Raja, V.; Majeed, U.; Kang, H.; Andrabi, K.I.; John, R. Abiotic Stress: Interplay between ROS, Hormones and MAPKs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 142–157.

- Rout, G.R.; Das, A.B. Molecular Stress Physiology of Plants. Mol. Stress Physiol. Plants 2013, 1–440.

- Yang, Y.; Sornaraj, P.; Borisjuk, N.; Kovalchuk, N.; Haefele, S.M. Transcriptional Network Involved in Drought Response and Adaptation in Cereals. In Abiotic Biotic Stress Plants—Recent Advances and Future Perspectives; InTech: Adelaide, Australia, 2016; pp. 3–30.

- Sinha, A.K.; Jaggi, M.; Raghuram, B.; Tuteja, N. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Plants under Abiotic Stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 196–203.

- Mittler, R.; Vanderauwera, S.; Gollery, M.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive Oxygen Gene Network of Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2004, 9, 490–498.

- Nakagami, H.; Kiegerl, S.; Hirt, H. OMTK1, a Novel MAPKKK, Channels Oxidative Stress Signaling through Direct MAPK Interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26959–26966.

- Nakashima, K.; Tran, L.P.; Van Nguyen, D.; Fujita, M.; Maruyama, K.; Todaka, D.; Ito, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Functional Analysis of a NAC-type Transcription Factor OsNAC6 Involved in Abiotic and Biotic Stress-responsive Gene Expression in Rice. Plant J. 2007, 51, 617–630.

- Xiong, L.; Zhu, J.-K. Regulation of Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 29–36.

- Jangale, B.L.; Chaudhari, R.S.; Azeez, A.; Sane, P.V.; Sane, A.P.; Krishna, B. Independent and Combined Abiotic Stresses Affect the Physiology and Expression Patterns of DREB Genes Differently in Stress-Susceptible and Resistant Genotypes of Banana. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 165, 303–318.

- Todaka, D.; Takahashi, F.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. ABA-Responsive Gene Expression in Response to Drought Stress: Cellular Regulation and Long-Distance Signaling; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 92.

- Cho, Y.-H.; Lee, S.; Yoo, S.-D. EIN2 and EIN3 in Ethylene Signalling. Annu. Plant Rev. Online 2018, 44, 169–187.

- Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.M.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Y. AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Regulatory Networks in Hormone and Abiotic Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1–17.

- Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Quan, R.; Li, G.; Wang, R.; Huang, R. An AP2 Domain-Containing Gene, ESE1, Targeted by the Ethylene Signaling Component EIN3 Is Important for the Salt Response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 854–865.

- De Geyter, N.; Gholami, A.; Goormachtig, S.; Goossens, A. Transcriptional Machineries in Jasmonate-Elicited Plant Secondary Metabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 349–359.

- Liu, L.; White, M.J.; Macrae, T.H. Functional Domains, Evolution and Regulation. Eur. J. Biochem 1999, 257, 247–257.

- Fujita, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Pivotal Role of the AREB/ABF-SnRK2 Pathway in ABRE-mediated Transcription in Response to Osmotic Stress in Plants. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 147, 15–27.

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.-Z.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R. Arabidopsis Transcription Factors: Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis among Eukaryotes. Science (80-) 2000, 290, 2105–2110.

- Liu, C.; Zhang, T. Expansion and Stress Responses of the AP2/EREBP Superfamily in Cotton. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 118.

- Phukan, U.J.; Jeena, G.S.; Tripathi, V.; Shukla, R.K. Regulation of Apetala2/Ethylene Response Factors in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–18.

- Dietz, K.-J.; Vogel, M.O.; Viehhauser, A. AP2/EREBP Transcription Factors Are Part of Gene Regulatory Networks and Integrate Metabolic, Hormonal and Environmental Signals in Stress Acclimation and Retrograde Signalling. Protoplasma 2010, 245, 3–14.

- Cheng, L.B.; Yang, J.J.; Yin, L.; Hui, L.C.; Qian, H.M.; Li, S.-Y.; Li, L.-J. Transcription Factor NnDREB1 from Lotus Improved Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Thaliana. Biol. Plant 2017, 61, 651–658.

- Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Gao, B.; Mijiti, M.; Bozorov, T.A.; Yang, H.; Zhang, D.; Wood, A.J. ScDREB10, an A-5c Type of DREB Gene of the Desert Moss Syntrichia Caninervis, Confers Osmotic and Salt Tolerances to Arabidopsis. Genes 2019, 10, 146.

- Yang, G.; Yu, L.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Gao, C. A ThDREB Gene from Tamarix Hispida Improved the Salt and Drought Tolerance of Transgenic Tobacco and T. Hispida. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 113, 187–197.

- Sharoni, A.M.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Satoh, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kondoh, H.; Sasaya, T.; Choi, I.R.; Omura, T.; Kikuchi, S. Gene Structures, Classification and Expression Models of the AP2/EREBP Transcription Factor Family in Rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 344–360.

- Yao, Y.; He, R.J.; Xie, Q.L.; Zhao, X.H.; Deng, X.M.; He, J.B.; Song, L.; He, J.; Marchant, A.; Chen, X. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 74 (ERF74) Plays an Essential Role in Controlling a Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog D (RbohD)-dependent Mechanism in Response to Different Stresses in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1667–1681.

- Hongxing, Z.; Benzhong, Z.; Bianyun, Y.; Yanling, H.; Daqi, F.; Wentao, X.; Yunbo, L. Cloning and DNA-Binding Properties of Ethylene Response Factor, LeERF1 and LeERF2, in Tomato. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005, 27, 423–428.

- Smita, S.; Katiyar, A.; Chinnusamy, V.; Pandey, D.M.; Bansal, K.C. Transcriptional Regulatory Network Analysis of MYB Transcription Factor Family Genes in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–19.

- Dubos, C.; Stracke, R.; Grotewold, E.; Weisshaar, B.; Martin, C.; Lepiniec, L. MYB Transcription Factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 573–581.

- Hasan, M.M.U.; Ma, F.; Islam, F.; Sajid, M.; Prodhan, Z.H.; Li, F.; Shen, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Biological Process and Key Pathway in Three Cotton (Gossypium Spp.) Species Under Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2076.

- Cao, Y.; Li, K.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L. MYB Transcription Factors as Regulators of Secondary Metabolism in Plants. Biology 2020, 9, 61.

- Dong, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Tang, S.; Liu, S.; Xia, X.; Yin, W. A Novel BHLH Transcription Factor PebHLH35 from Populus Euphratica Confers Drought Tolerance through Regulating Stomatal Development, Photosynthesis and Growth in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 453–458.

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Sui, N. Transcriptional Regulation of BHLH during Plant Response to Stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 503, 397–401.

- Wang, R.; Zhao, P.; Kong, N.; Lu, R.; Pei, Y.; Huang, C.; Ma, H.; Chen, Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the Potato BHLH Transcription Factor Family. Genes 2018, 9, 54.

- Wang, L.; Xiang, L.; Hong, J.; Xie, Z.; Li, B. Genome-Wide Analysis of BHLH Transcription Factor Family Reveals Their Involvement in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 236.

- Cui, X.; Wang, Y.-X.; Liu, Z.-W.; Wang, W.-L.; Li, H.; Zhuang, J. Transcriptome-Wide Identification and Expression Profile Analysis of the BHLH Family Genes in Camellia Sinensis. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2018, 18, 489–503.