| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nacksung Kim | + 2083 word(s) | 2083 | 2021-07-08 12:06:49 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2083 | 2021-07-20 03:13:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

Coupled signaling between bone-forming osteoblasts and bone-resorbing osteoclasts is crucial to the maintenance of bone homeostasis. We previously reported that v-crk avian sarcoma virus CT10 oncogene homolog-like (CrkL), which belongs to the Crk family of adaptors, inhibits bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2)-mediated osteoblast differentiation, while enhancing receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclast differentiation. In this study, we investigated whether CrkL can also regulate the coupling signals between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, facilitating bone homeostasis. Osteoblastic CrkL strongly decreased RANKL expression through its inhibition of runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) transcription. Reduction in RANKL expression by CrkL in osteoblasts resulted in the inhibition of not only osteoblast-dependent osteoclast differentiation but also osteoclast-dependent osteoblast differentiation, suggesting that CrkL participates in the coupling signals between osteoblasts and osteoclasts via its regulation of RANKL expression. Therefore, CrkL bifunctionally regulates osteoclast differentiation through both a direct and indirect mechanism while it inhibits osteoblast differentiation through its blockade of both BMP2 and RANKL reverse signaling pathways. Collectively, these data suggest that CrkL is involved in bone homeostasis, where it helps to regulate the complex interactions of the osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and their coupling signals.

1. Introduction

2.Bifunctional Role of CrkL during Bone Remodeling

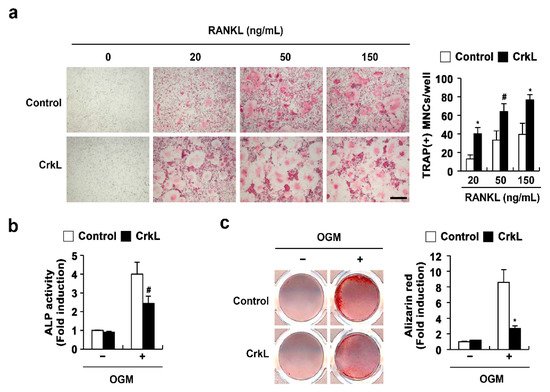

2.1. CrkL Has a Positive and Negative Effect on Osteoclast and Osteoblast Differentiation, Respectively

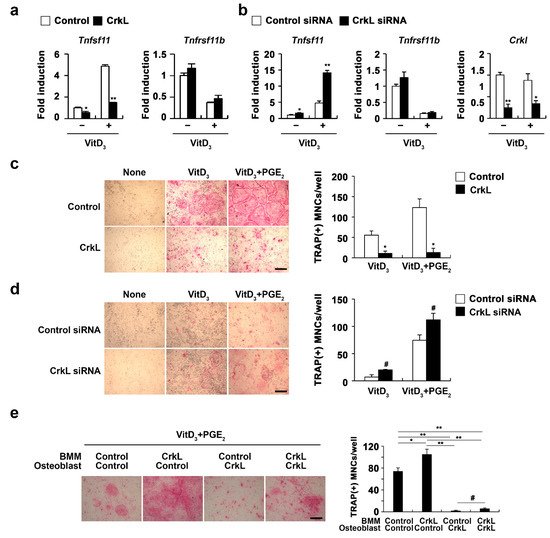

2.2. CrkL Indirectly Inhibits Osteoclast Differentiation by Regulating RANKL (Tnfsf11) Expression

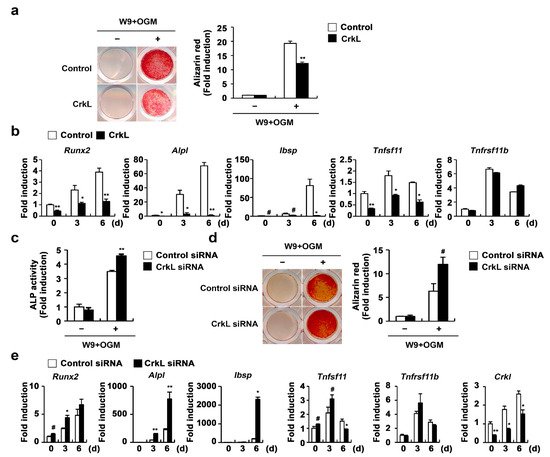

2.3. CrkL Inhibits RANKL-Mediated Osteoblast Differentiation

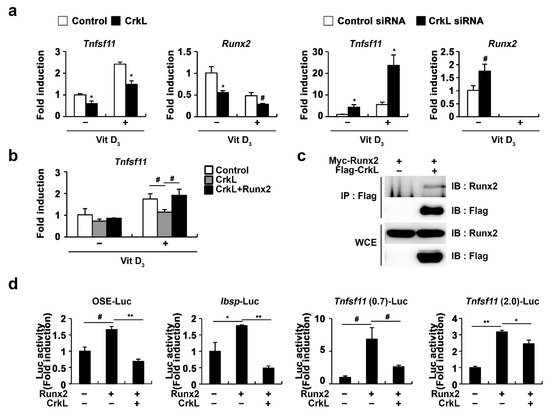

2.4. CrkL Inhibits RANKL Expression via Interaction with Runx2

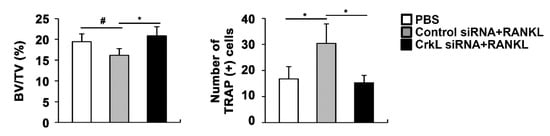

2.5. Downregulation of CrkL Can Protect RANKL-Induced Bone Loss In Vivo

3. Conclusions

References

- Walsh, M.C.; Kim, N.; Kadono, Y.; Rho, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Lorenzo, J.; Choi, Y. Osteoimmunology: Interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 24, 33–63.

- Cappariello, A.; Maurizi, A.; Veeriah, V.; Teti, A. The Great Beauty of the osteoclast. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 558, 70–78.

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, N. Signaling Pathways in Osteoclast Differentiation. Chonnam Med. J. 2016, 52, 12–17.

- Kim, B.J.; Koh, J.M. Coupling factors involved in preserving bone balance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1243–1253.

- Rodan, G.A.; Martin, T.J. Role of osteoblasts in hormonal control of bone resorption—A hypothesis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1981, 33, 349–351.

- Tamma, R.; Zallone, A. Osteoblast and osteoclast crosstalks: From OAF to Ephrin. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2012, 11, 196–200.

- Mundy, G.R.; Eleftesriou, F. Boning up on ephrin signaling. Cell 2006, 126, 441–443.

- Sambandam, Y.; Blanchard, J.J.; Daughtridge, G.; Kolb, R.J.; Shanmugarajan, S.; Pandruvada, S.N.; Bateman, T.A.; Reddy, S.V. Microarray profile of gene expression during osteoclast differentiation in modelled microgravity. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010, 111, 1179–1187.

- Anderson, D.M.; Maraskovsky, E.; Billingsley, W.L.; Dougall, W.C.; Tometsko, M.E.; Roux, E.R.; Teepe, M.C.; DuBose, R.F.; Cosman, D.; Galibert, L. A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature 1997, 390, 175–179.

- Wong, B.R.; Rho, J.; Arron, J.; Robinson, E.; Orlinick, J.; Chao, M.; Kalachikov, S.; Cayani, E.; Bartlett, F.S., 3rd; Frankel, W.N.; et al. TRANCE is a novel ligand of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family that activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase in T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 25190–25194.

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Karray, S.; Shi, S.; Jin, Y. Osteoblast-induced osteoclast apoptosis by fas ligand/FAS pathway is required for maintenance of bone mass. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 1654–1664.

- Matsuoka, K.; Park, K.A.; Ito, M.; Ikeda, K.; Takeshita, S. Osteoclast-derived complement component 3a stimulates osteoblast differentiation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1522–1530.

- Negishi-Koga, T.; Shinohara, M.; Komatsu, N.; Bito, H.; Kodama, T.; Friedel, R.H.; Takayanagi, H. Suppression of bone formation by osteoclastic expression of semaphorin 4D. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1473–1480.

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Miron, R.J.; Shi, B.; Bian, Z. Anabolic bone formation via a site-specific bone-targeting delivery system by interfering with semaphorin 4D expression. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 286–296.

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Duan, N.; Zhu, G.; Schwarz, E.M.; Xie, C. Osteoblast-osteoclast interactions. Connect. Tissue Res. 2018, 59, 99–107.

- Yuan, F.L.; Wu, Q.Y.; Miao, Z.N.; Xu, M.H.; Xu, R.S.; Jiang, D.L.; Ye, J.X.; Chen, F.H.; Zhao, M.D.; Wang, H.J.; et al. Osteoclast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Novel Regulators of Osteoclastogenesis and Osteoclast-Osteoblasts Communication in Bone Remodeling. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 628.

- Sims, N.A.; Martin, T.J. Coupling Signals between the Osteoclast and Osteoblast: How are Messages Transmitted between These Temporary Visitors to the Bone Surface? Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6, 41.

- Chang, B.; Quan, Q.; Li, Y.; Qiu, H.; Peng, J.; Gu, Y. Treatment of Osteoporosis, with a Focus on 2 Monoclonal Antibodies. Med Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 8758–8766.

- Qaseem, A.; Forciea, M.A.; McLean, R.M.; Denberg, T.D. Treatment of Low Bone Density or Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures in Men and Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update From the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 818–839.

- Cotts, K.G.; Cifu, A.S. Treatment of Osteoporosis. JAMA 2018, 319, 1040–1041.

- Rachner, T.D.; Khosla, S.; Hofbauer, L.C. Osteoporosis: Now and the future. Lancet 2011, 377, 1276–1287.

- Cosman, F.; de Beur, S.J.; LeBoff, M.S.; Lewiecki, E.M.; Tanner, B.; Randall, S.; Lindsay, R. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014, 25, 2359–2381.

- Shigeno-Nakazawa, Y.; Kasai, T.; Ki, S.; Kostyanovskaya, E.; Pawlak, J.; Yamagishi, J.; Okimoto, N.; Taiji, M.; Okada, M.; Westbrook, J.; et al. A pre-metazoan origin of the CRK gene family and co-opted signaling network. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34349.

- Roy, N.H.; Mammadli, M.; Burkhardt, J.K.; Karimi, M. CrkL is required for donor T cell migration to GvHD target organs. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1505–1514.

- Song, Q.; Yi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.K.J.; Wei, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y. CRKL regulates alternative splicing of cancer-related genes in cervical cancer samples and HeLa cell. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 499.

- Birge, R.B.; Kalodimos, C.; Inagaki, F.; Tanaka, S. Crk and CrkL adaptor proteins: Networks for physiological and pathological signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2009, 7, 13.

- Ren, R.; Ye, Z.S.; Baltimore, D. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase selects the Crk adapter as a substrate using SH3-binding sites. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 783–795.

- Sakai, R.; Iwamatsu, A.; Hirano, N.; Ogawa, S.; Tanaka, T.; Mano, H.; Yazaki, Y.; Hirai, H. A novel signaling molecule, p130, forms stable complexes in vivo with v-Crk and v-Src in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 3748–3756.

- De Jong, R.; ten Hoeve, J.; Heisterkamp, N.; Groffen, J. Crkl is complexed with tyrosine-phosphorylated Cbl in Ph-positive leukemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 21468–21471.

- Salgia, R.; Uemura, N.; Okuda, K.; Li, J.L.; Pisick, E.; Sattler, M.; de Jong, R.; Druker, B.; Heisterkamp, N.; Chen, L.B.; et al. CRKL links p210BCR/ABL with paxillin in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 29145–29150.

- Salgia, R.; Pisick, E.; Sattler, M.; Li, J.L.; Uemura, N.; Wong, W.K.; Burky, S.A.; Hirai, H.; Chen, L.B.; Griffin, J.D. p130CAS forms a signaling complex with the adapter protein CRKL in hematopoietic cells transformed by the BCR/ABL oncogene. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 25198–25203.

- Ribon, V.; Hubbell, S.; Herrera, R.; Saltiel, A.R. The product of the cbl oncogene forms stable complexes in vivo with endogenous Crk in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 45–52.

- Beitner-Johnson, D.; Blakesley, V.A.; Shen-Orr, Z.; Jimenez, M.; Stannard, B.; Wang, L.M.; Pierce, J.; LeRoith, D. The proto-oncogene product c-Crk associates with insulin receptor substrate-1 and 4PS. Modulation by insulin growth factor-I (IGF) and enhanced IGF-I signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9287–9290.

- Sattler, M.; Salgia, R.; Okuda, K.; Uemura, N.; Durstin, M.A.; Pisick, E.; Xu, G.; Li, J.L.; Prasad, K.V.; Griffin, J.D. The proto-oncogene product p120CBL and the adaptor proteins CRKL and c-CRK link c-ABL, p190BCR/ABL and p210BCR/ABL to the phosphatidylinositol-3’ kinase pathway. Oncogene 1996, 12, 839–846.

- Akagi, T.; Shishido, T.; Murata, K.; Hanafusa, H. v-Crk activates the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway in transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7290–7295.

- Sattler, M.; Salgia, R.; Shrikhande, G.; Verma, S.; Uemura, N.; Law, S.F.; Golemis, E.A.; Griffin, J.D. Differential signaling after beta1 integrin ligation is mediated through binding of CRKL to p120(CBL) and p110(HEF1). J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 14320–14326.

- Sattler, M.; Salgia, R.; Shrikhande, G.; Verma, S.; Pisick, E.; Prasad, K.V.; Griffin, J.D. Steel factor induces tyrosine phosphorylation of CRKL and binding of CRKL to a complex containing c-kit, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and p120(CBL). J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 10248–10253.

- Gesbert, F.; Garbay, C.; Bertoglio, J. Interleukin-2 stimulation induces tyrosine phosphorylation of p120-Cbl and CrkL and formation of multimolecular signaling complexes in T lymphocytes and natural killer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 3986–3993.

- Koval, A.P.; Karas, M.; Zick, Y.; LeRoith, D. Interplay of the proto-oncogene proteins CrkL and CrkII in insulin-like growth factor-I receptor-mediated signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 14780–14787.

- Fish, E.N.; Uddin, S.; Korkmaz, M.; Majchrzak, B.; Druker, B.J.; Platanias, L.C. Activation of a CrkL-stat5 signaling complex by type I interferons. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 571–573.

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, I.; Seong, S.; Nam, K.I.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, N. Adaptor protein CrkII negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation and function through JNK phosphorylation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–10.

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, I.; Seong, S.; Nam, K.I.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, N. Role of CrkII Signaling in RANKL-Induced Osteoclast Differentiation and Function. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 1123–1131.

- Guris, D.L.; Fantes, J.; Tara, D.; Druker, B.J.; Imamoto, A. Mice lacking the homologue of the human 22q11.2 gene CRKL phenocopy neurocristopathies of DiGeorge syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 293–298.

- Park, T.J.; Boyd, K.; Curran, T. Cardiovascular and craniofacial defects in Crk-null mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 6272–6282.

- Ikebuchi, Y.; Aoki, S.; Honma, M.; Hayashi, M.; Sugamori, Y.; Khan, M.; Kariya, Y.; Kato, G.; Tabata, Y.; Penninger, J.M.; et al. Coupling of bone resorption and formation by RANKL reverse signalling. Nature 2018, 561, 195–200.

- Ozaki, Y.; Koide, M.; Furuya, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Yasuda, H.; Nakamura, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Yoshinari, N.; Udagawa, N. Treatment of OPG-deficient mice with WP9QY, a RANKL-binding peptide, recovers alveolar bone loss by suppressing osteoclastogenesis and enhancing osteoblastogenesis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184904.

- Sawa, M.; Wakitani, S.; Kamei, N.; Kotaka, S.; Adachi, N.; Ochi, M. Local administration of WP9QY (W9) peptide promotes bone formation in a rat femur delayed-union model. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2018, 36, 383–391.

- Otsuki, Y.; Ii, M.; Moriwaki, K.; Okada, M.; Ueda, K.; Asahi, M. W9 peptide enhanced osteogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 904–910.

- Geoffroy, V.; Kneissel, M.; Fournier, B.; Boyde, A.; Matthias, P. High bone resorption in adult aging transgenic mice overexpressing cbfa1/runx2 in cells of the osteoblastic lineage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 6222–6233.

- Enomoto, H.; Shiojiri, S.; Hoshi, K.; Furuichi, T.; Fukuyama, R.; Yoshida, C.A.; Kanatani, N.; Nakamura, R.; Mizuno, A.; Zanma, A.; et al. Induction of osteoclast differentiation by Runx2 through receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand (RANKL) and osteoprotegerin regulation and partial rescue of osteoclastogenesis in Runx2−/− mice by RANKL transgene. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 23971–23977.

- Yahiro, Y.; Maeda, S.; Morikawa, M.; Koinuma, D.; Jokoji, G.; Ijuin, T.; Komiya, S.; Kageyama, R.; Miyazono, K.; Taniguchi, N. BMP-induced Atoh8 attenuates osteoclastogenesis by suppressing Runx2 transcriptional activity and reducing the Rankl/Opg expression ratio in osteoblasts. Bone Res. 2020, 8, 32.

- Byon, C.H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J.; Yuan, K.; Mao, X.; Heath, J.M.; Anderson, P.G.; Tintut, Y.; Demer, L.L.; Wang, D.; et al. Runx2-upregulated receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand in calcifying smooth muscle cells promotes migration and osteoclastic differentiation of macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1387–1396.