| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jordi Camps | + 1891 word(s) | 1891 | 2021-07-09 06:09:48 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 1891 | 2021-07-09 09:55:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

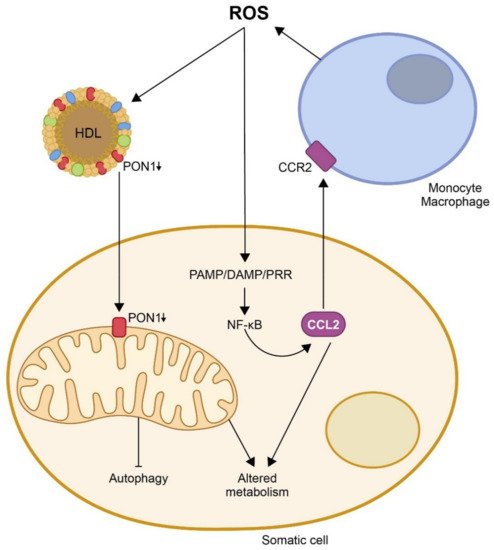

Infectious and many non-infectious diseases share common molecular mechanisms. Among them, oxidative stress and the subsequent inflammatory reaction are of particular note. Metabolic disorders induced by external agents, be they bacterial or viral pathogens, excessive calorie intake, poor-quality nutrients, or environmental factors produce an imbalance between the production of free radicals and endogenous antioxidant systems; the consequence being the oxidation of lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids. Oxidation and inflammation are closely related, and whether oxidative stress and inflammation represent the causes or consequences of cellular pathology, both produce metabolic alterations that influence the pathogenesis of the disease. In this entry, authors highlight two key molecules in the regulation of these processes: Paraoxonase-1 (PON1) and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2).

1. Oxidation, Inflammation and Disease

2. The Protective Role of Paraoxonases on CCL2 Expression, Mitochondrial Function, and Metabolism

3. Mechanism of Action of CCL2 in the Immune Response and Inflammation and Its Relationship with Multiple Metabolic Alterations

References

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763.

- Masud, S.; Torraca, V.; Meijer, A.H. Modeling infectious diseases in the context of a developing immune system. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2017, 124, 277–329.

- He, J.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Tang, X.; Xiao, H.; Hu, Z. Oxidative Stress, inflammation, and autophagy: Potential targets of mesenchymal stem cells-based therapies in ischemic stroke. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 641157.

- Kibel, A.; Lukinac, A.M.; Dambic, V.; Juric, I.; Relatic, K.S. Oxidative stress in ischemic heart disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6627144.

- Atri, C.; Guerfali, F.Z.; Laouini, D. Role of human macrophage polarization in inflammation during infectious diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1801.

- Parisi, L.; Gini, E.; Baci, D.; Tremolati, M.; Fanuli, M.; Bassani, B.; Farronato, G.; Bruno, A.; Mortara, L. Macrophage polarization in chronic inflammatory diseases: Killers or builders? J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 8917804.

- Poltavets, A.S.; Vishnyakova, P.A.; Elchaninov, A.V.; Sukhikh, G.T.; Fatkhudinov, T.K. Macrophage modification strategies for efficient cell therapy. Cells 2020, 9, 1535.

- Viola, A.; Munari, F.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, R.; Scolaro, T.; Castegna, A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1462.

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2563–2582.

- Gschwandtner, M.; Derler, R.; Midwood, K.S. More than just attractive: How CCL2 influences myeloid cell behavior beyond chemotaxis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2759.

- Huang, R.; Guo, L.; Gao, M.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. Research trends and regulation of CCL5 in prostate cancer. Onco. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 1417–1427.

- Agresti, N.; Lalezari, J.P.; Amodeo, P.P.; Mody, K.; Mosher, S.F.; Seethamraju, H.; Kelly, S.A.; Pourhassan, N.Z.; Sudduth, C.D.; Bovinet, C.; et al. Disruption of CCR5 signaling to treat COVID-19-associated cytokine storm: Case series of four critically ill patients treated with leronlimab. J. Transl. Autoimmun. 2021, 4, 100083.

- Yao, X.; Matosevic, S. Chemokine networks modulating natural killer cell trafficking to solid tumors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 36–45.

- Necula, D.; Riviere-Cazaux, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, M. Insight into the roles of CCR5 in learning and memory in normal and disordered states. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 92, 1–9.

- Manco, G.; Porzio, E.; Carusone, T.M. Human paraoxonase-2 (PON2): Protein functions and modulation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 256.

- Horke, S.; Witte, I.; Wilgenbus, P.; Krüger, M.; Strand, D.; Förstermann, U. Paraoxonase-2 reduces oxidative stress in vascular cells and decreases endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced caspase activation. Circulation 2007, 115, 2055–2064.

- Horke, S.; Witte, I.; Wilgenbus, P.; Altenhöfer, S.; Krüger, M.; Li, H.; Förstermann, U. Protective effect of paraoxonase-2 against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis is lost upon disturbance of calcium homoeostasis. Biochem. J. 2008, 416, 395–405.

- Devarajan, A.; Grijalva, V.R.; Bourquard, N.; Meriwether, D.; Imaizumi, S.; Shin, B.C.; Devaskar, S.U.; Reddy, S.T. Macrophage paraoxonase 2 regulates calcium homeostasis and cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress conditions and is sufficient to prevent the development of aggravated atherosclerosis in paraoxonase 2 deficiency/apoE-/- mice on a Western diet. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012, 107, 416–427.

- Sulaiman, D.; Li, J.; Devarajan, A.; Cunningham, C.M.; Li, M.; Fishbein, G.A.; Fogelman, A.M.; Eghbali, M.; Reddy, S.T. Paraoxonase 2 protects against acute myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating mitochondrial function and oxidative stress via the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β RISK pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 129, 154–164.

- Tao, S.; Niu, L.; Cai, L.; Geng, Y.; Hua, C.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone modulates mitochondrial function and suppresses proliferation in intestinal goblet cells. Life Sci. 2018, 201, 81–88.

- Tao, S.; Luo, Y.; Bin, H.; Liu, J.; Qian, X.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, R. Paraoxonase 2 modulates a proapoptotic function in LS174T cells in response to quorum sensing molecule N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28778.

- García-Heredia, A.; Kensicki, E.; Mohney, R.P.; Rull, A.; Triguero, I.; Marsillach, J.; Tormos, C.; Mackness, B.; Mackness, M.; Shih, D.M.; et al. Paraoxonase-1 deficiency is associated with severe liver steatosis in mice fed a high-fat high-cholesterol diet: A metabolomic approach. J. Proteome Res. 2013, 12, 1946–1955.

- Luciano-Mateo, F.; Cabré, N.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Hernández- Aguilera, A.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Mercado-Gómez, M.; Menendez, J.A.; Camps, J.; Joven, J. Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 gene ablation protects low-density lipoprotein and paraoxonase-1 double deficient mice from liver injury, oxidative stress and inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mold Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1555–1566.

- Meneses, M.J.; Silvestre, R.; Sousa-Lima, I.; Macedo, M.P. Paraoxonase-1 as a regulator of glucose and lipid homeostasis: Impact on the onset and progression of metabolic disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4049.

- Calvo, N.; Beltrán-Debón, R.; Rodríguez-Gallego, E.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Guirro, M.; Mariné-Casadó, R.; Millá, L.; Alegret, J.M.; Sabench, F.; del Castillo, D.; et al. Liver fat deposition and mitochondrial dysfunction in morbid obesity: An approach combining metabolomics with liver imaging and histology. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 7529–7544.

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Fibla, M.; Fernández-Julià, R.; París, M.; Sabench, F.; Castillo, D.D.; et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy reverses non-alcoholic fatty liver disease modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolism 2019, 99, 81–89.

- Cabré, N.; Luciano-Mateo, F.; Baiges-Gayà, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; París, M.; Sabench, F.; Del Castillo, D.; López-Miranda, J.; et al. Plasma metabolic alterations in patients with severe obesity and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 374–387.

- Kurihara, C.; Lecuona, E.; Wu, Q.; Yang, W.; Núñez-Santana, F.L.; Akbarpour, M.; Liu, X.; Ren, Z.; Li, W.; Querrey, M.; et al. Crosstalk between nonclassical monocytes and alveolar macrophages mediates transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury through classical monocyte recruitment. JCI Insight 2021, 6, 147282.

- Mohammed, S.; Nicklas, E.H.; Thadathil, N.; Selvarani, R.; Royce, G.H.; Kinter, M.; Richardson, A.; Deepa, S.S. Role of necroptosis in chronic hepatic inflammation and fibrosis in a mouse model of increased oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 164, 315–328.

- Zhu, F.; Willette-Brown, J.; Zhang, J.; Ferre, E.M.N.; Sun, Z.; Wu, X.; Lionakis, M.S.; Hu, Y. NLRP3 inhibition ameliorates severe cutaneous autoimmune manifestations in a mouse model of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy-like disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 141, 1404–1415.

- McKnight, A.H.; Katzenberger, D.R.; Britnell, S.R. Colchicine in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 55, 187–197.

- Kolattukudy, P.E.; Niu, J. Inflammation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/CCR2 pathway. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 174–189.

- Pandey, E.; Nour, A.S.; Harris, E.N. Prominent receptors of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in liver homeostasis and disease. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 873.

- Andersson, U.; Ottestad, W.; Tracey, K.J. Extracellular HMGB1: A therapeutic target in severe pulmonary inflammation including COVID-19? Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 42.

- Shamilov, R.; Ackley, T.W.; Aneskievich, B.J. Enhanced wound healing- and inflammasome-associated gene expression in TNFAIP3-interacting protein 1-(TNIP1-) deficient HaCaT keratinocytes parallels reduced reepithelialization. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 5919150.

- Relja, B.; Land, W.G. Damage-associated molecular patterns in trauma. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 46, 751–775.

- Afrose, S.S.; Junaid, M.; Akter, Y.; Tania, M.; Zheng, M.; Khan, M.A. Targeting kinases with thymoquinone: A molecular approach to cancer therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today. 2020, 25, 2294–2306.

- Dantonio, P.M.; Klein, M.O.; Freire, M.R.V.B.; Araujo, C.N.; Chiacetti, A.C.; Correa, R.G. Exploring major signaling cascades in melanomagenesis: A rationale route for targetted skin cancer therapy. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180511.

- Stawski, L.; Trojanowska, M. Oncostatin M and its role in fibrosis. Connect. Tissue Res. 2019, 60, 40–49.

- Slaine, P.D.; Kleer, M.; Duguay, B.A.; Pringle, E.S.; Kadijk, E.; Ying, S.; Balgi, A.; Roberge, M.; McCormick, C.; Khaperskyy, D.A. Thiopurines activate an antiviral unfolded protein response that blocks influenza A virus glycoprotein accumulation. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e00453-21.

- Féral, K.; Jaud, M.; Philippe, C.; Di Bella, D.; Pyronnet, S.; Rouault-Pierre, K.; Mazzolini, L.; Touriol, C. ER Stress and unfolded protein response in leukemia: Friend, foe, or both? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 199.

- Huang, J.; Pan, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Huo, X.; Ma, Y.; Lu, Z.; Sun, B.; Jiang, H. Unfolded protein response in colorectal cancer. Cell. Biosci. 2021, 11, 26.

- Robinson, C.M.; Talty, A.; Logue, S.E.; Mnich, K.; Gorman, A.M.; Samali, A. An emerging role for the unfolded protein response in pancreatic cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 261.

- Morris, G.; Puri, B.K.; Walder, K.; Berk, M.; Stubbs, B.; Maes, M.; Carvalho, A.F. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in neuroprogressive diseases: Emerging pathophysiological role and translational implications. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 8765–8787.

- Rashid, H.O.; Yadav, R.K.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. ER stress: Autophagy induction, inhibition and selection. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1956–1977.

- Dymkowska, D. The involvement of autophagy in the maintenance of endothelial homeostasis: The role of mitochondria. Mitochondrion 2021, 57, 131–147.

- Picca, A.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Junior, H.J.; Marzetti, E. Cell death and inflammation: The role of mitochondria in health and disease. Cells 2021, 10, 537.

- Su, Y.J.; Wang, P.W.; Weng, S.W. The role of mitochondria in immune-cell-mediated tissue regeneration and ageing. Int. J. Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 2668.

- Jang, J.Y.; Blum, A.; Liu, J.; Finkel, T. The role of mitochondria in aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3662–3670.

- Meyers, A.K.; Zhu, X. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Metabolic regulation and contribution to inflammaging. Cells 2020, 9, 1808.

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217.

- Fulop, T.; Witkowski, J.M.; Olivieri, F.; Larbi, A. The integration of inflammaging in age-related diseases. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 40, 17–35.

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 2010, 140, 900–917.

- Berent-Maoz, B.; Montecino-Rodriguez, E.; Signer, R.A.; Dorshkind, K. Fibroblast growth factor-7 partially reverses murine thymocyte progenitor aging by repression of Ink4a. Blood 2012, 119, 5715–5721.

- Sierra-Filardi, E.; Nieto, C.; Domínguez-Soto, A.; Barroso, R.; Sánchez-Mateos, P.; Puig-Kroger, A.; López-Bravo, M.; Joven, J.; Ardavín, C.; Rodríguez-Fernández, J.L.; et al. CCL2 shapes macrophage polarization by GM-CSF and M-CSF: Identification of CCL2/CCR2-dependent gene expression profile. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 3858–3867.

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Schafer, M.J.; Noren Hooten, N.; Atkinson, E.J.; Evans, M.K.; Baker, D.J.; Quarles, E.K.; Robbins, P.D.; Ladiges, W.C.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; et al. Circulating levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 as a potential measure of biological age in mice and frailty in humans. Aging Cell 2018, 17, e12706.

- Acosta, J.C.; Banito, A.; Wuestefeld, T.; Georgilis, A.; Janich, P.; Morton, J.P.; Athineos, D.; Kang, T.W.; Lasitschka, F.; Andrulis, M.; et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2013, 15, 978–990.

- Lee, J.Y.; Yu, K.R.; Lee, B.C.; Kang, I.; Kim, J.J.; Jung, E.J.; Kim, H.S.; Seo, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Kang, K.S. GATA4-dependent regulation of the secretory phenotype via MCP-1 underlies lamin a-mediated human mesenchymal stem cell aging. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–12.

- Luciano-Mateo, F.; Cabré, N.; Baiges-Gaya, G.; Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Hernández-Aguilera, A.; Rodríguez-Tomàs, E.; Arenas, M.; Camps, J.; Menéndez, J.A.; Joven, J. Systemic overexpression of C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 promotes metabolic dysregulation and premature death in mice with accelerated aging. Aging 2020, 12, 20001–20023.

- Hoyt, L.R.; Randall, M.J.; Ather, J.L.; DePuccio, D.P.; Landry, C.C.; Qian, X.; Janssen-Heininger, Y.M.; van der Vliet, A.; Dixon, A.E.; Amiel, E.; et al. Mitochondrial ROS induced by chronic ethanol exposure promote hyper-activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Redox. Biol. 2017, 12, 883–896.

- Lavallard, V.; Cottet-Dumoulin, D.; Wassmer, C.H.; Rouget, C.; Parnaud, G.; Brioudes, E.; Lebreton, F.; Bellofatto, K.; Berishvili, E.; Berney, T.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome is activated in rat pancreatic islets by transplantation and hypoxia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7011.

- Fusco, R.; Gugliandolo, E.; Siracusa, R.; Scuto, M.; Cordaro, M.; D’Amico, R.; Evangelista, M.; Peli, A.; Peritore, A.F.; Impellizzeri, D.; et al. Formyl peptide receptor 1 signaling in acute inflammation and neural differentiation induced by traumatic brain injury. Biology 2020, 9, 238.