The clinical reports published since the first outbreaks in December 2020 have indicated which part of the population is more at risk. In we have summarized the findings of several studies, where advancing age [

35], male sex, and the presence of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease seem to represent the main risk factors for severe outcomes [

36]. Recently, obesity has been indicated as an additional risk factor, which can promote severe outcome in subjects infected with SARS-CoV-2. Kompaniyets and colleagues have reported a relationship between body mass index (BMI) and severe infection, probably due to the high level of inflammation characteristic of obese people [

37].

In fact, after one year in this pandemic, although COVID19 has been shown to spread among young and middle-aged people, where only a small percentage develop severe symptoms [

47,

48], indicating that our efforts should be concentrated towards finding better therapies in subjects that are often treated for other pathologies. It is crucial to understand to what extent underlying diseases and their treatment could represent a risk factor for severe outcomes. Another important aspect to note is the risk of concomitant bacterial infection, which has previously been shown to exacerbate the symptoms of influenza viruses [

49].

Today, there are no specific treatments for COVID-19 and all strategies being applied are entirely supportive [

3], with many clinical trials underway that have not yet offered definitive support to any particular treatment. Since the beginning of this pandemic, different classes of drugs or treatments have been tested against SARS-CoV-2 infection, including anti-viral (AV) drugs, anti-inflammatory (AI), monoclonal antibody (MA), plasma therapy (PT) and cell-based therapy (CT).

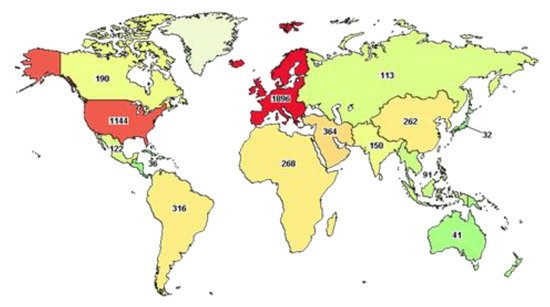

At the time of writing, the website clinicaltrial.gov reports more than five thousand clinical trials underway worldwide (), of which 980 have been completed.

An advanced search shows that half of these trials (2554) are focused on subjects older than 65 years, as discussed above, demonstrating the urgency of finding better therapies for the strata of the population that has suffered more from the effects of this pandemic. Among these trials, only 17 have been completed and they include the use of Ivermectin (AV), alone or in combination with Doxycycline, Hydroxychloroquine monotherapy (AV) and in combination with Azithromycin (AI), Favipavir (AV), Remdesivir (AV), Convalescent Plasma. Ivermectin is an FDA-approved AV drug, known since 1981 and proven to work against different RNA viruses, such as Avian influenza A, Zika, yellow fever, dengue, among others, and recently shown to completely block SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro. This drug is normally well tolerated, with minimal side effects and, hopefully, when published, the results of these clinical trials will advise its use in COVID-19 subjects [

50]. Other AV drugs, Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine, have been shown to inhibit viral entry, but the clinical reports published are vague and often present many limitations, such as an inadequate number of patients and no medical or safety outcome being described [

51,

52]. It is also worth remembering that both drugs have been shown to cause severe side effects, such as cardiotoxicity and hypoglycemia [

53,

54] that, as described previously, could cause harm in particular subjects with cardiovascular disease or diabetes who are more at risk of developing severe COVID-19 infection. Furthermore, more precautions should be used in subjects with Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency [

55]. Remdesivir (AV), proposed as a treatment for Ebola, blocks viral RNA replication through the inhibition of RdRp and has been demonstrated to control SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro and in vivo [

56]. The final report published on 1062 patients demonstrated that Remdesivir improved recovery in adults with COVID-19 and the decrease in mortality rate was statistically significant [

57]. Like Remdesivir, Favipavir (AV) is an antiviral drug, able to inhibit the RdRp and, although the data of the current clinical trial have not been published yet, early indications have demonstrated a decreased viral load in COVID-19 patients [

58]. Different studies have shown that plasma from convalescent patients (CP) can also improve the clinical outcome in severely ill patients [

59], although this may not be the best therapeutic strategy when an extremely high number of patients needs to be treated. Beyond the molecules just described, many other repurposed FDA-approved drugs have been used to treat SARS-CoV-2 infections. For the sake of space, and because the description of the molecular mechanisms specific to each drug is beyond the scope of this review, we have listed them in and refer the readers to other works, where their mode of action is described in detail [

60].