| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mladenka Malenica | + 4000 word(s) | 4000 | 2021-06-04 03:45:18 | | | |

| 2 | Nora Tang | Meta information modification | 4000 | 2021-06-28 04:25:33 | | | | |

| 3 | Nora Tang | Meta information modification | 4000 | 2021-06-28 04:39:22 | | | | |

| 4 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4000 | 2021-10-11 02:53:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

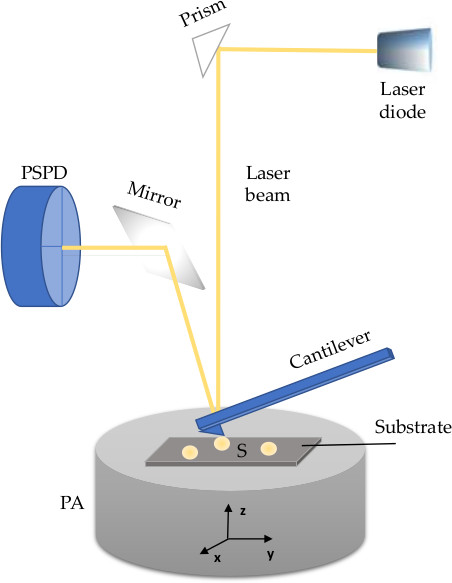

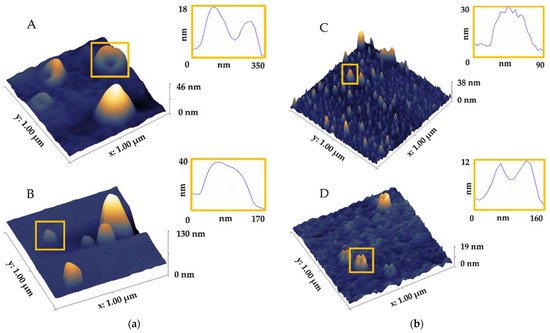

Advanced and optimised microscopy methods, including atomic force microscopy (AFM), are required to visualise and characterise morphology of extracellular vesicles (EVs), a heterogenous groups of nanoparticles regarded as highly promising source of diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools. EVs are nanosized phospholipid membranous structures ubiquitously found in human biofluids, secreted from almost every cell, and thus reflect both physiological and pathophysiological changes of their parental cells. The lipid membrane of an EV contains proteins (e.g., tetraspanins, receptors and other molecules) and diverse luminal content with bioactive cargo that includes nucleic acids (DNA, mRNA, miRNA and lncRNA), proteins, organelles, or infectious particles. AFM is a nanoscale tool for the determination of morphology, structure and composition, but also biomechanics and biophysical characteristics of nanometric structures. Briefly, AFM uses a micrometric cantilever with a nanometre-sized tip actuated by piezoelectric crystals. Upon receiving signals of a tip-sample interaction, a position-sensitive photodiode (PSPD) converts it to a voltage and sends it to a piezoelectric actuator (PA). The latter expands and contracts proportionally to the applied voltage to manipulate the sample and the probe position across three dimensions with high precision. The PA can be coupled to a cantilever or positioned under a sample holder. The whole system is controlled by suitable control electronics.

1. AFM modes

2. Operating environments of AFM

3. Cantilevers and Drives

4. Sample Preparation for AFM Imaging

5. Aplication of AFM in Characterization of EVs from Human Biofluids

| Method | Biofluid | Shape | Structure/Morphology/Topography | Size (nm) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFM air |

saliva | ring-like irregular vs. round circular |

with central indentation trilobed membrane individual vs. aggregated heterogeneous vs. homogeneous aggregated vs. single bulging agglomerates less dense periphery/more dense core larger vesicles without dense core clusters |

50–70 around 100 >100 40–80 20–400 |

[2][18][31] |

| urine | round | individual vesicles, no aggregation | / | [32] | |

| blood | spheroidal near-spherical cup-shape |

increased stiffness irreversible deformation |

~30 high/~90 wide 23.7 high/71.3 lateral 3.16 high/31.2 lateral 60–100 |

[6][15][25] | |

| AFM liquid |

saliva | ring-like | with central indentation trilobed membrane |

50–70around 100 | [2] |

| blood | spheroidal spherical cup-shape disc-like |

various structures soft inner cavity stiffer membrane softer vs. stiffer |

~30 high/~90 wide ~25 high 50–140 6.26 high/70.55 lateral 4.16 high/16.3 lateral |

[4][15][25][33][34] |

References

- Sharma, S.; LeClaire, M.; Gimzewski, J.K. Ascent of Atomic Force Microscopy as a Nanoanalytical Tool for Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 132001.

- Sharma, S.; Rasool, H.I.; Palanisamy, V.; Mathisen, C.; Schmidt, M.; Wong, D.T.; Gimzewski, J.K. Structural-Mechanical Characterization of Nanoparticle Exosomes in Human Saliva, Using Correlative AFM, FESEM, and Force Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 1921–1926.

- Ito, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Yokota, K.; Matsumura, S.; Minamisawa, T.; Suga, K.; Shiba, K.; Kimura, Y.; Hirano-Iwata, A.; Takamura, Y.; et al. Host Cell Prediction of Exosomes Using Morphological Features on Solid Surfaces Analyzed by Machine Learning. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6224–6235.

- Vorselen, D.; van Dommelen, S.M.; Sorkin, R.; Piontek, M.C.; Schiller, J.; Döpp, S.T.; Kooijmans, S.A.A.; van Oirschot, B.A.; Versluijs, B.A.; Bierings, M.B.; et al. The Fluid Membrane Determines Mechanics of Erythrocyte Extracellular Vesicles and Is Softened in Hereditary Spherocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4960.

- Galvanetto, N. Practical Applications of Atomic Force Microscopy in Biomedicine. STE Med. 2020, 1, e15.

- Hardij, J.; Cecchet, F.; Berquand, A.; Gheldof, D.; Chatelain, C.; Mullier, F.; Chatelain, B.; Dogné, J.-M. Characterisation of Tissue Factor-Bearing Extracellular Vesicles with AFM: Comparison of Air-Tapping-Mode AFM and Liquid Peak Force AFM. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2013, 2, 21045.

- LeClaire, M.; Gimzewski, J.; Sharma, S. A Review of the Biomechanical Properties of Single Extracellular Vesicles. Nano Select 2021, 2, 1–15.

- Nguyen, T.D.; Gu, Y. Investigation of Cell-Substrate Adhesion Properties of Living Chondrocyte by Measuring Adhesive Shear Force and Detachment Using AFM and Inverse FEA. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38059.

- Parisse, P.; Rago, I.; Ulloa Severino, L.; Perissinotto, F.; Ambrosetti, E.; Paoletti, P.; Ricci, M.; Beltrami, A.P.; Cesselli, D.; Casalis, L. Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 813–820.

- Skliar, M.; Chernyshev, V.S. Imaging of Extracellular Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, e59254.

- Aliofkhazraei, M.; Ali, N. 7.09—AFM Applications in Micro/Nanostructured Coatings. In Comprehensive Materials Processing; Hashmi, S., Batalha, G.F., Van Tyne, C.J., Yilbas, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 191–241. ISBN 978-0-08-096533-8.

- Chernyshev, V.S.; Rachamadugu, R.; Tseng, Y.H.; Belnap, D.M.; Jia, Y.; Branch, K.J.; Butterfield, A.E.; Pease, L.F.; Bernard, P.S.; Skliar, M. Size and Shape Characterization of Hydrated and Desiccated Exosomes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 3285–3301.

- Dufrêne, Y.F.; Ando, T.; Garcia, R.; Alsteens, D.; Martinez-Martin, D.; Engel, A.; Gerber, C.; Müller, D.J. Imaging Modes of Atomic Force Microscopy for Application in Molecular and Cell Biology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2017, 12, 295–307.

- Labuda, A.; Hohlbauch, S.; Kocun, M.; Limpoco, F.T.; Kirchhofer, N.; Ohler, B.; Hurley, D. Tapping Mode AFM Imaging in Liquids with BlueDrive Photothermal Excitation. Micros. Today 2018, 26, 12–17.

- Sebaihi, N.; De Boeck, B.; Yuana, Y.; Nieuwland, R.; Pétry, J. Dimensional Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017, 28, 034006.

- Beekman, P.; Enciso-Martinez, A.; Rho, H.S.; Pujari, S.P.; Lenferink, A.; Zuilhof, H.; Terstappen, L.W.M.M.; Otto, C.; Le Gac, S. Immuno-Capture of Extracellular Vesicles for Individual Multi-Modal Characterization Using AFM, SEM and Raman Spectroscopy. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 2526–2536.

- Sharma, S.; LeClaire, M.; Wohlschlegel, J.; Gimzewski, J. Impact of Isolation Methods on the Biophysical Heterogeneity of Single Extracellular Vesicles. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13327.

- Zlotogorski-Hurvitz, A.; Dayan, D.; Chaushu, G.; Korvala, J.; Salo, T.; Sormunen, R.; Vered, M. Human Saliva-Derived Exosomes: Comparing Methods of Isolation. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 181–189.

- Garcia, P.S.; Brum, D.G.; Oliveira, O.N.; Higa, A.M.; Ierich, J.C.M.; de Moraes, A.S.; Shimizu, F.M.; Okuda-Shinagawa, N.M.; Peroni, L.A.; da Gama, P.D.; et al. Nanoimmunosensor Based on Atomic Force Spectroscopy to Detect Anti-Myelin Basic Protein Related to Early-Stage Multiple Sclerosis. Ultramicroscopy 2020, 211, 112946.

- Chuo, S.T.-Y.; Chien, J.C.-Y.; Lai, C.P.-K. Imaging Extracellular Vesicles: Current and Emerging Methods. J. Biomed. Sci. 2018, 25, 91.

- Müller, D.J.; Dufrêne, Y.F. Atomic Force Microscopy: A Nanoscopic Window on the Cell Surface. Trends. Cell Biol. 2011, 21, 461–469.

- Brachmann, E.; Seifert, M.; Oswald, S.; Menzel, S.B.; Gemming, T. Evaluation of Surface Cleaning Procedures for CTGS Substrates for SAW Technology with XPS. Materials 2017, 10, 1373.

- Royo, F.; Gil-Carton, D.; Gonzalez, E.; Mleczko, J.; Palomo, L.; Perez-Cormenzana, M.; Mayo, R.; Alonso, C.; Falcon-Perez, J.M. Differences in the Metabolite Composition and Mechanical Properties of Extracellular Vesicles Secreted by Hepatic Cellular Models. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1575678.

- Cavallaro, S.; Pevere, F.; Stridfeldt, F.; Görgens, A.; Paba, C.; Sahu, S.S.; Mamand, D.R.; Gupta, D.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Linnros, J.; et al. Multiparametric Profiling of Single Nanoscale Extracellular Vesicles by Combined Atomic Force and Fluorescence Microscopy: Correlation and Heterogeneity in Their Molecular and Biophysical Features. Small 2021, 17, 2008155.

- Bairamukov, V.; Bukatin, A.; Landa, S.; Burdakov, V.; Shtam, T.; Chelnokova, I.; Fedorova, N.; Filatov, M.; Starodubtseva, M. Biomechanical Properties of Blood Plasma Extracellular Vesicles Revealed by Atomic Force Microscopy. Biology 2020, 10, 4.

- Ji, Y.; Qi, D.; Li, L.; Su, H.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, F.; Lin, B.; Liu, T.; et al. Multiplexed Profiling of Single-Cell Extracellular Vesicles Secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5979–5984.

- Gajos, K.; Kamińska, A.; Awsiuk, K.; Bajor, A.; Gruszczyński, K.; Pawlak, A.; Żądło, A.; Kowalik, A.; Budkowski, A.; Stępień, E. Immobilization and Detection of Platelet-Derived Extracellular Vesicles on Functionalized Silicon Substrate: Cytometric and Spectrometric Approach. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1109–1119.

- Dagur, R.S.; Liao, K.; Sil, S.; Niu, F.; Sun, Z.; Lyubchenko, Y.L.; Peeples, E.S.; Hu, G.; Buch, S. Neuronal-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Enriched in the Brain and Serum of HIV-1 Transgenic Rats. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1703249.

- Gandham, S.; Su, X.; Wood, J.; Nocera, A.L.; Alli, S.C.; Milane, L.; Zimmerman, A.; Amiji, M.; Ivanov, A.R. Technologies and Standardization in Research on Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1066–1098.

- Ashcroft, B.A.; de Sonneville, J.; Yuana, Y.; Osanto, S.; Bertina, R.; Kuil, M.E.; Oosterkamp, T.H. Determination of the Size Distribution of Blood Microparticles Directly in Plasma Using Atomic Force Microscopy and Microfluidics. Biomed. Microdevices. 2012, 14, 641–649.

- Sharma, S.; Gillespie, B.M.; Palanisamy, V.; Gimzewski, J.K. Quantitative Nanostructural and Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy Biomolecular Analysis of Human-Saliva-Derived Exosomes. Langmuir 2011, 27, 14394–14400.

- Yang, M.; Zhi, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Alfranca, G.; Xia, F.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Cui, D. High-Purified Isolation and Proteomic Analysis of Urinary Exosomes from Healthy Persons. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2017, 9, 221–227.

- Rikkert, L.G.; Beekman, P.; Caro, J.; Coumans, F.A.W.; Enciso-Martinez, A.; Jenster, G.; Le Gac, S.; Lee, W.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Loozen, G.B.; et al. Cancer-ID: Toward Identification of Cancer by Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Blood. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 608.

- Dobra, G.; Bukva, M.; Szabo, Z.; Bruszel, B.; Harmati, M.; Gyukity-Sebestyen, E.; Jenei, A.; Szucs, M.; Horvath, P.; Biro, T.; et al. Small Extracellular Vesicles Isolated from Serum May Serve as Signal-Enhancers for the Monitoring of CNS Tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5359.