| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shumei Zhai | + 7052 word(s) | 7052 | 2021-04-26 03:33:31 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 7052 | 2021-06-25 04:11:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

Due to the small size, nanoparticles have the potential to cross the placental barrier and cause toxicity in the fetus.

1. Introduction

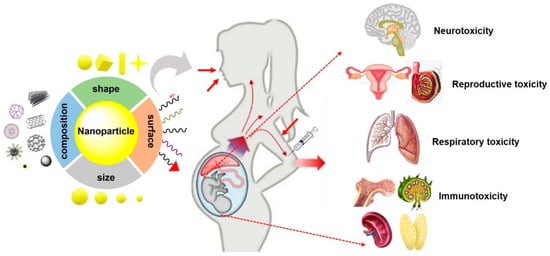

The rapid development of nanotechnology has led to the increased production and use of nanomaterials in industry, biomedicine, and everyday life [1][2][3], thus highlighting the need for a rise in biosafety evaluation, especially for susceptible populations [4][5][6][7]. Among these, pregnant women and developing embryos/fetuses are more vulnerable to xenobiotics. Embryo–fetal development is a critical window of exposure-related susceptibility because the etiology of diseases in adulthood may have a fetal origin. Due to their unique physicochemical properties, nanoparticles (NPs) have the tendency to cross the blood–placental barrier and reach the fetus, leading to various fetal abnormalities. In utero exposures to nanomaterials not only cause adverse pregnancy outcomes and intrauterine fetal development but also lead to the occurrence of adult chronic diseases [8][9].

So far, numerous studies have indisputably demonstrated that maternal exposure to nanomaterials during gestation result in fetotoxicity, including adverse prenatal effects on the fetus [10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17], neurotoxicity [18][19][20][21][22][23], reproductive toxicity [24][25][26][27][28], immunotoxicity [29][30][31][32] and respiratory toxicity [29][33][34][35] in offspring or even in adulthood [16][17][18][36]. The direct translocation of NPs or indirect interference from maternal damage-induced maternal mediators and placental mediators contributes to the fetotoxicity induced by prenatal exposure to NPs [37][38].

2. NPs-Induced Fetotoxicity

2.1. Adverse Prenatal Effects on Gestational Parameters

Recent epidemiological studies have indicated a significant association between maternal occupational exposure to NPs and being small for gestational age [39][40]. Maternal NP exposure induces detrimental prenatal outcomes such as low birth weight, preterm birth, miscarriage, fetal resorption, morphological malformations, intrauterine growth retardation, and other embryo–fetal developmental abnormalities (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of gestational parameters induced following maternal exposure to nanoparticles (NPs).

|

NPs |

Animals/Exposure Route |

Fetotoxicities |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CeO2 NPs 3–5 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 5 mg/kg, GD5, 6, and 7 |

Decreased number and pups’ weight; increased fetal resorption rate |

[10] |

|

ZnO NPs 13 nm |

Mouse, i.g., GD7-GD16 |

Intrauterine growth retardation |

[11] |

|

Ultrafine particles |

Mouse, intratracheal instillation, 400 μg/kg, GD7, 9, 11, 15 and 17 |

Embryo reabsorption, decreased fetal weight and altered blood pressure in the offspring |

[12] |

|

QDs |

Rat, inhalation exposure, 5,1 nmol/rat, GD5–GD19 |

Growth restriction in offspring |

[13] |

|

Ag NPs 18–20 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 640 μg/m3, GD1–GD15 |

Increased number of resorbed fetuses |

[14] |

|

CdSe/ZnS QDs, 20 nm CdSe QDs, 15 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 0.1 nmol/mouse, GD17 and 18 |

Fetus malformation, hampered growth |

[15] |

|

SiO2 NPs, 70 nm TiO2 NPs, 35 nm |

Mouse, i.v., SiO2 NPs: 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 mg/mouse, TiO2 NPs: 0.8 mg/mouse, GD16 and 17 |

Smaller fetuses |

[16] |

|

p,o,uo-SWCNTs |

Mouse, the retrobulbar injection, 0.01~30 μg/mouse, GD6 |

Retarded limbs and snout development |

[17] |

|

Diesel engine exhaust (DEP), 69 nm |

Rabbit, nose-only inhalation, 2 h/day, 5 days/week, GD3–GD27 |

Growth retardation at mid gestation with decreased head length and umbilical pulse |

[41] |

|

NP-enriched DE, 22–27 nm |

Rat, intranasal instillation, 148.86 μg/m3, 3.10 μg/m3, 5 h/day, GD1–GD19 |

Increased fetal weight and decreased crown-rump length |

[42] |

|

CB NPs 14 nm |

Mouse, intratracheal instillation, 11, 54, 268 μg/mouse, GD7, 10, 15 and 18 |

Induced more DNA strand breaks in the liver of their offspring |

[43] |

|

MWCNTs |

Mouse, i.p. or intratracheal instillation, 2, 3, 4, 5 mg/kg, GD9 |

Increased the number of external malformation and skeletal malformation in fetuses |

[44] |

|

SWCNTs |

Rat, intratracheal instillation or i.v., 100 μg/kg, GD17–GD19 |

Induced vasoconstriction and reduced fetal growth |

[45] |

|

rGO |

Mouse, i.v., 6.25, 12.5, 25 mg/kg, GD6 or 20 |

Caused malformation in fetuses |

[46] |

|

ZnO NPs 30 nm |

Mouse, i.g., 20, 60, 180, 540 mg/kg, GD11–GD18 |

Fetal growth retardation, decreased fetal number |

[47] |

|

ZnO 13, 57 or 1900 nm |

Mouse, i.g., GD7–GD16 |

Decreased birth weight |

[48] |

|

ZnO NPs 44.2 nm |

Rat, i.v., 5, 10, 20 mg/kg, GD7–GD21 |

Increased the number of dead fetuses and decreased fetal weight |

[49] |

|

ZnO NPs 20 nm |

Mouse, i.g., 100, 200, 400 mg/kg, GD5–GD19 |

Significant decrease in fetal weight for 400 mg/kg exposure group |

[50] |

|

ZnO NPs 35 nm |

Rat, i.g., 500 mg/kg, 2 weeks before mating to PND 4 |

Reduced fetal weight and increased fetal resorption of pups |

[51] |

|

TiO2 NPs 21 nm |

Rat, inhalation exposure, 12 mg/m3, 6 h/exposure, 6 days, GD11–GD16 |

Significantly decreased pup’s weight and placental efficiency |

[52] |

|

TiO2 NPs 6.5 nm |

Mouse, i.g., 25, 50, 100 mg/kg, GD1–GD18 |

Inhibited the crown-rump length, fetal weight, the number of live fetuses and fetal skeleton development |

[53] |

|

SiO2 NPs 25, 60, 115 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 3, 30, 200 μg/mouse, GD6, 13 and 17 |

Decreased the resorbed number at the dose of 200 μg/mouse for 25 nm NPs |

[54] |

|

CdO NPs 11–15 nm |

Mouse, inhalation exposure, 100 μg/m3, every other day or 230 μg/m3 daily, 2.5 h/day, GD5–GD17 |

Decreased incidence of pregnancy, fetal length, and neonatal growth |

[55] |

|

Ag NPs 20, 110 nm |

Rat, i.v., 200 μg/rat, GD17–GD19 |

Fetal growth restriction |

[56] |

|

Ag NP 10 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 66 μg/mouse, GD8–GD10 |

Embryonic growth restriction |

[57] |

|

Au NPs 2, 15, 50 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 2 mg/kg, or 0.5–10 mg/kg, GD4–GD6 |

Disturb embryonic development in a size- and concentration-dependent manner. |

[58] |

|

ZnO NPs SiO2 NPs |

Mouse, i.g., ZnO NPs: 50, 100, 300 mg/kg, SiO2 NPs: 50, 100 mg/kg, GD5–GD19 |

Miscarriages and adversely affected the developing fetus |

[59] |

|

PEI-Fe2O3-NPs, 28 nm PAA-Fe2O3-NPs, 30 nm |

Mouse, i.p., 10, 100 mg/kg, GD9, 10 and 11 |

High dose exposure led to charge-dependent fetal loss, morphological alterations in uteri |

[60] |

|

TiO2 NPs 20 nm |

Rat, inhalation exposure, 10 mg/m3, 6 h/exposure, 6 days, GD5–GD19 |

Altered fetal epigenome |

[61] |

|

QDs 1.67, 2.59 or 3.21 nm |

Mouse, i.p., 5, 10, 20 mg/kg, GD14 |

Decreased survival rate, body length, body mass and disturbed ossification of limbs |

[62] |

|

Fe2O3 NPs 28–30 nm |

Mouse, i.p., 10 mg/kg, GD10–GD17 |

Increased fetal death |

[63] |

|

SiO2 NPs 70 nm |

Mouse, i.v., 25, 40 mg/kg, GD13–GD14 |

Pregnancy complications |

[64] |

|

o-MWCNTs |

Mouse, i.v., 20 mg/kg, GD4, 11 and 15 |

Induced maternal body weight gain and abortion rates dependent on pregnancy times |

[65] |

|

CNTs |

Mouse, i.v., 10 μg/mouse, GD6 and 15 |

Occasional teratogenic effects |

[66] |

|

fCNTs |

Mouse, i.g., 10 mg/kg, GD9 |

Increased the number of resorbed fetuses; fetal morphological and skeletal abnormalities |

[67] |

|

TiO2 NPs Ag NPs |

Mouse, i.g., 10, 100, 1000 mg/kg, GD9 |

Increase fetal mortality |

[68] |

|

DEPs |

Mouse, i.g., 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 mg/kg, GD11–GD16 |

Increased the frequency of DNA deletions in fetus and offspring |

[69] |

Abbreviations: GD, gestational day; PND, postnatal day; i.v., intravenous; i.g., intragastrical; i.p., intraperitoneal; Ref., references; QDs, quantum dots; SWCNTs, single-walled carbon nanotubes; DE, diesel exhaust CB, carbon black; MWCNTs, multi-walled carbon nanotubes; CNTs, carbon nanotubes; rGO, reduced graphene oxide; PEI, polyethyleneimine; PAA, poly(acrylic acid).

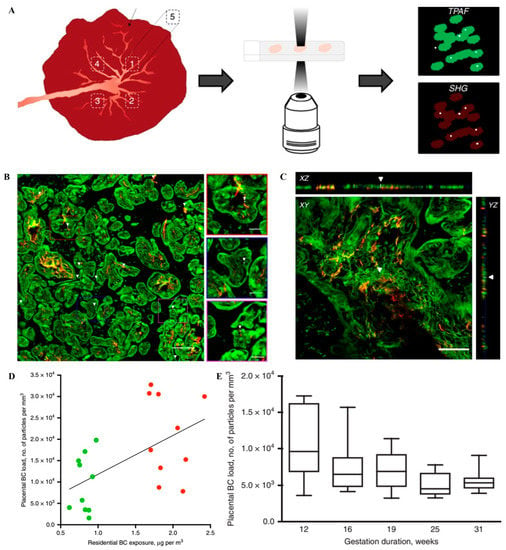

Ambient fine or ultrafine particles. Air pollution is a global threat to health. The potential detrimental effects of ambient (ultra)fine particles on fetal and child development have been evidenced. For example, pregnant C57BL/6J pun/pun female mice were intratracheally instilled with collected ultrafine particles at the accumulated dose of 400 μg/kg every other day during gestational day 7 (GD7)-GD17 to evaluate the fetal development under the adverse intrauterine environment induced by particulate matter (PM) [12]. This in utero ultrafine particle exposure induced placental dysfunction, which resulted in embryo reabsorption and a significant decrease in fetal weight. Daily nose-only exposure to diesel exhaust (DE) damaged placental function and induced early signs of growth retardation in a pregnant rabbit model [41]. However, another research suggested that it is the toxic chemicals but not the NPs in NP-rich diesel exhaust (NR-DE) or filtered diesel exhaust (F-DE) might be responsible for disrupting steroid hormone production in the corpus luteum and adrenal cortex in pregnant rats, which showed fetal weight and decreased fetal crown–rump length [42]. Recently, a study has shown that black carbon (BC) particles, a component of combustion-related particulate matter (PM), can reach the fetal side of the human placenta (Figure 1), which suggested that ambient particulates could be transported towards the fetus and represented a potential mechanism explaining the detrimental health effects of pollution from early life onwards [36].

Figure 1. The protocol for black carbon detection in the placenta and evidence of them at the fetal side of human placenta. (A) The detection of BC particles in placenta. The white light produced by the BC naturally present in the tissue (white dots) is detected along with the simultaneous generation and detection of two-photon excited autofluorescence (TPAF) of the cells (green) and second harmonic generation (SHG) from collagen (red). (B) The evidence of ambient BC particles at the fetal side of human placenta. White light (WL) generation originating from the BC particles (white and further indicated using white arrowheads) under femtosecond pulsed laser illumination (excitation 810 nm, 80 MHz, 10 mW laser power on the sample) is observed. Scale bar: 30 μm. (C) Validation of the carbonaceous nature of the identified particles inside the placenta. XY-images acquired throughout a placental section in the z-direction and corresponding orthogonal XZ-projections and YZ-projections showing a BC particle (white and indicated by white arrowheads) inside the tissue (red and green). Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Correlation between placental load and residential exposure of CB particles throughout the whole pregnancy. The line is the regression line. Green and red dots indicate low (n = 10 mothers) and high (n = 10 mothers) exposed mothers. (E) BC load in placentas from spontaneous preterm births (n = 5). The whiskers indicate the minimum and maximum value and the box of the box plot illustrates the upper and lower quartile. The median of spreading is marked by a horizontal line within the box. Reproduced with permission [36]. Copyright Springer Nature, 2019.

Carbon-based nanomaterials. Carbon-based nanomaterials, such as carbon black (CB), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and fullerenes are produced and widely used in the industry. Their biosafety has become a major concern. When pregnant C57BL/6BomTac mice were administered with CB NPs (14 nm) via lung exposure, both inhalation exposure (42 mg/m3, 1 h/day) from GD8–GD18 (11, 54 and 268 mg/mouse) and intratracheal instillation induced maternal inflammation [43]. Maternal exposure during pregnancy to CNTs, including single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), and functionalized CNTs, increased early miscarriages, fetal resorption rate, external defects, and skeletal abnormalities in fetuses. For instance, pregnant ICR mice were given a single intraperitoneal (2–5 mg/kg) or intratracheal (3–5 mg/kg) administration of MWCNTs on GD9 to assess embryo–fetal developmental toxicity. The results showed that both exposure routes caused various types of morphological and skeletal malformations. Short or absent tails and fusion of the ribs or vertebral bodies were observed in all intraperitoneally treated groups; these malformations were also observed in intratracheal exposure groups with a higher dose (4/5 mg/kg) [44]. Both intratracheal instillation and intravenous injection of MWCNTs (100 μg/kg) from GD17–GD19 led to decreased fetal weight [45]. Qi et al. reported that oxidized MWCNTs, which primarily accumulated in the liver, lung, and heart of the fetus, caused fetal development delay, fetal heart and brain disruption, and fetal resorption. Furthermore, maternal exposure to MWCNTs might induce transplacental mutagenesis [70]. Other reports showed that the intratracheal instillation of MWCNTs at a single dose (67 μg/mouse) interfered with ovulation; however, no significant alterations in litter or gestational parameters, such as implantations, sex ratio, litter size, and implantation loss, were observed [26][71]. The repeated oral administration of MWCNTs (8, 40, 200, or 1000 mg/kg) during organogenesis (GD6-GD19) did not induce alterations in gestational parameters [72][73]. These results indicated that NP administration routes affected fetal toxicities, with oral administration or via inhalation showing less toxicities than intravenous injection.

The surface modification of NPs could affect nanotoxicity. When pregnant mice were intravenously injected with amino-functionalized polyethylene glycol (PEG)-SWCNTs at a single dose of 0.1, 10, and 30 μg/mouse on GD6 or in multiple administrations of 10 μg/mouse on GD6, GD9, and GD12 (total dose of 30 μg/mouse), occasional teratogenic effects were observed only at a dose of 30 μg/mouse, possibly due to their transfer to the fetal–placenta unit. Functionalized SWCNTs significantly increased fetal resorptions, morphological abnormalities and skeletal deformities following a single oral exposure of 10 mg/kg on GD9. Ultraoxide-functionalization aggravated the toxicity of SWCNTs considerably with the higher induction of early miscarriages and fetal resorptions compared with pristine or oxidized SWCNTs [17]. The intravenous administration of reduced graphene oxide (rGO, 6.25, 12.5, and 25mg/kg) nanosheets into pregnant dams in the late gestational stage (~GD20) induced much more miscarriage than in the early gestational stage (~GD6) [46]. These results indicated that surface modification, administration routes, and gestational stages were the main factors contributing to the embryotoxic development of NPs.

Metal oxide NPs. Metal oxide NPs, especially zinc oxide NPs (ZnO NPs) and titanium dioxide NPs (TiO2 NPs), have become one of the most promising nanomaterials due to their wide application in sunscreens, food, biomedicine, and environmental remediation. Thus, their potential toxicity after maternal exposure has gained more attention. The oral administration of zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs, once daily by gavage during the organogenesis period, retarded fetal growth, reduced live fetal number, and increased fetal resorption and abnormalities [11][47][48][49][50][51]. Chen et al. found similar embryotoxicity at a dose of 180 or 540 mg/kg [47]. ZnO NPs induced such adverse effects in a size-dependent (13 nm and 57 nm, 200 mg/kg) and gestational stage-dependent manner (GD7–GD16, GD1–GD10) after a 10-day oral exposure [48]. When pregnant mice were intravenously injected with ZnO NPs (44 nm, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) from GD6–GD20, an increased number of dead fetuses, post-implantation loss, and reduced fetal weight were observed in the 20 mg/kg treatment group [49]. These results indicated that maternal exposure to ZnO NPs during pregnancy might pose health risks to both pregnant mothers and fetuses, which were dependent on the size of ZnO NPs, exposure time, exposure dose, and administration routes. Notably, the toxicity induced by zinc ion dissociated from ZnO NPs needs to be considered, in particular for oral administration.

Maternal exposure to TiO2 NPs during pregnancy induced alterations in gestational parameters, such as increased fetal resorption rate, smaller uteri and fetuses, and skeletal abnormalities in fetuses [16][52][53][74]. When intravenously injected into pregnant BALB/c mice, TiO2 NPs and SiO2 NPs (70 nm) significantly enhanced the fetal resorption rate, and decreased the fetal weight and uterine weight [16], which were dependent on the size, surface modification of NPs, and exposure stages of pregnancy [16][54]. Time-mated mice (ICR) were orally administered with TiO2 NPs (25, 50 and 100 mg/kg) during the whole gestation to investigate their adverse effects on the developing fetus [53]. TiO2 NPs transferred through the placenta, accumulated in the fetus and suppressed fetal development. Maternal inhalation exposure to TiO2 NPs (21 nm) during organogenesis decreased pup weight due to reduced placenta efficiency. However, in another study, no alterations in gestational parameters, such as litter size, fetal weight, sex distribution, and implantations, were observed [74]. The possible reason might be different sizes for adopted TiO2 NPs. The maternal–fetal transfer and accumulation of food-grade TiO2 NPs in the human placenta and meconium emphasized the need for the risk assessment of chronic exposure to TiO2-NPs during pregnancy [75].

Maternal exposure to other metal oxide NPs during pregnancy such as CeO2 NPs and CdO NPs also led to poor pregnancy outcomes [10][55]. The intravenous injection of CeO2 NPs into pregnant mice at a dose of 5 mg/kg daily from GD5–GD7 resulted in aberrations in decidualization, which exhibited “ripple effects” leading to fetal loss, fetal growth retardation, placental dysfunction, and even infertility [10]. When pregnant mice (ICR) were exposed to CdO NPs (11–15 nm) via nose-only inhalation either every other day (100 mg/m3) or daily (230 mg/m3) for 2.5 h/exposure from GD5–GD17, the accumulation of CdO NPs in placenta decreased the fetal length and delayed neonatal growth without direct NP transfer to the fetus [55].

Metal NPs. The extensive application and large-scale production of metal NPs, such as Ag NPs and Au NPs, raise safety concerns in the vulnerable stages of life. A single intravenous administration of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) or citrate-coated Ag NPs (20 or 110 nm, 700 μg/kg) in the late stages of pregnancy produced moderate size- and vehicle-dependent alterations in vascular tissue contractility, suggesting possible fetal growth retardation [56]. Nose-only inhalation exposure to freshly produced Ag NP aerosol (18–20 nm, 1 or 4 h/day) during GD1–GD15 induced the translocation of Ag NPs and increased the number of resorbed fetuses [14]. The intravenous injection of 10 nm Ag NPs (66 mg/mouse) daily on GD7, GD8, and GD9 led to significant Ag accumulation in the maternal liver, spleen, and visceral yolk sac, and might potentially affect embryonic growth without accumulation in embryos/fetuses [57]. Au NPs (2, 15, and 50 nm) disturb embryonic development in a size- and concentration-dependent manner. Au NPs (15 nm) downregulated the expression of distinct germ layer markers and suppressed the differentiation of all three embryonic germ layers, consequently leading to fetal resorption [58].

In summary, in utero exposure to NPs induced potential fetal developmental toxicity or teratogenicity, such as fetal growth retardation, decreased litter size, fetal deformities, and fetal resorption. NP-induced embryo–fetal developmental toxicity depended on not only the physiochemical properties of NPs but also the exposure schedule, including administration doses and times, as well as maternal pathophysiological conditions.

2.2. Neurotoxicity

Maternal exposure to xenobiotics usually causes the most common developmental abnormalities in humans, especially those associated with neurodevelopment in fetus/offspring. Previous studies demonstrated that ultrafine particles/NPs penetrated through the blood–brain barrier, reached the brain, and induced neurodevelopmental toxicity [76][77][78][79]. With the incomplete blood–brain barrier, fetal brains are more vulnerable to xenobiotic pollutants, leading to pathological abnormalities in fetal brain tissues and neural damage in offspring brains, and even behavioral abnormalities in adulthood. Prenatal exposures to DEP [20][80][81], CB NPs [22][82][83][84], CNTs [70], ZnO NPs [85], TiO2 NPs [19][23][86][87][88][89], and Ag NPs [90] induced various organic and functional damages to the central nervous system (CNS) (Table 2).

Table 2. NP-induced neurotoxicity following maternal exposure during pregnancy.

|

NPs |

Animals/Exposure Route |

Neurotoxicity |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

TiO2 NPs 6.5 nm |

Mouse, i.g., 1.25, 2.5, 5 mg/kg, GD7–PND21 |

Retarded axonal and dendritic outgrowth |

[19] |

|

DE |

Mouse, s.c., 0.5, 1 mg/mL, GD5, 8, 11, 14 and 17 |

Increased glial-fibrillary acidic protein level in the corpus callosum and cortex |

[20] |

|

CoCr NPs |

Mouse, i.v., 0.12 mg/mouse, GD10 and 13 |

Neurodevelopmental abnormalities with reactive astrogliosis and increased DNA damage in fetal hippocamus |

[21] |

|

CB NPs |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 2.9, 15, 73 μg/kg, GD5 and 9 |

Reactive astrogliosis |

[22] |

|

TiO2 NPs 25–70 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 1 μg/μL, 100 μL, GD7, 10, 13 and 16 |

Changed gene expression related to neurotransmitters and psychiatric diseases in newborns |

[23] |

|

SWCNTs |

Mouse, i.v., 2 mg/kg, GD11, 13, and 16 |

Obvious brain deformity |

[70] |

|

TiO2 NPs 21 nm |

Mouse, inhalation exposure, 42 mg/m3, 1 h/day, GD8–GD18 |

Moderate neurobehavioral alterations in offspring mice |

[74] |

|

CB NPs 100–300 nm |

Mouse, airway instillation, 0, 4.6, 37 mg/m3, 15 days, GD4–GD18 |

Denaturation of perivascular macrophages and reactive astrocytes |

[82] |

|

CB NPs 84 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 190 μg/kg, GD5 and 7 |

Gene dysfunction in the frontal cortex in offspring mice |

[83] |

|

CB NPs 84.2 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 95 μg/kg, GD5 and 9 |

Astrogliosis in the offspring brain |

[84] |

|

ZnO NPs 30 nm |

Rat, ig., 500 mg/kg, GD2–GD19 |

Learning and memory impairment in the offspring brain |

[85] |

|

TiO2 NPs |

Mouse, i.v., 100, 1000 μg, every second day, GD9 |

Autism spectrum disorder-related behavioral deficits in the offspring |

[86] |

|

TiO2 NPs 10 nm |

Rat, i.g., 100 mg/kg, GD2–GD21 |

Impaired memory and decreased hippocampal cell proliferation in rat offspring |

[88] |

|

TiO2 NPs 5 nm |

Rat, s.c., 1 μg/μL, 500 μL, GD7, 10, 13, 16 and 19 |

Oxidative damage in the brain of newborn pups, and the depressive-like behaviors during adulthood |

[89] |

|

Ag NPs 10 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 0.2, 2 mg/kg, once every three days, GD1–GD21 |

Gender-specific depression-like behaviors in offspring |

[90] |

|

Ultrafine particles |

Mouse, airway instillation, 92.69 μg/m3, 6 h/day, GD1–GD17 |

Neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring |

[91] |

|

TiO2 NPs 6.5 nm |

Rat, i.g., 100 mg/kg, GD2–GD21, PND2–PND21 |

Impacted hippocampal neurogenesis and apoptosis in the offspring |

[92] |

|

TiO2 NPs 6.5 nm |

Mouse, i.g., 1, 2, 3 mg/kg, GD1–PND21 |

Inhibited dendritic outgrowth of hippocampal neurons in the offspring mice |

[93] |

|

ZnO NPs 20–40 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 4 h/day, PND4–PND7, PND10–PND13 |

Decreased ambulation score, hindlimb suspension score and degree of grip strength; increased degree of hindlimb foot angle |

[94] |

|

ZnO NPs 20–40 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 0.5, 1 mg/mL, GD5, 8, 11, 14 and 17 |

Depressive-like behaviors in offspring |

[95] |

|

TiO2 NPs 20 nm |

Mouse, i.p., 2 mg/mL, GD11– GD16 |

Decreased size and weight of fetus, a disrupted anatomical structure of the fetal brain, bulkier and abnormal shape of fetal liver |

[96] |

|

TiO2 NPs 170.9 nm |

Rat, airway instillation, 10.4 mg/m3, 5 h/day, 4 days/week, GD7–GD20 |

Induced psychological deficits in male adulthood rat |

[97] |

|

Ag NPs 10 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 0.2, 2 mg/kg, once every three days, GD1–GD21 |

Neurobehavioral disorders in the offspring |

[98] |

|

USPIO NPs |

Mouse, i.v., 6.25, 12.5, 25 mg/kg, GD6 or 20 |

Abnormal fetal neurodevelopment |

[99] |

Abbreviations: GD, gestational day; i.v., intravenous; i.g., intragastrical; i.p., intraperitoneal; s.c., subcutaneous; USPIO, ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide; Ref., references.

Ambient fine or ultrafine particles. Epidemiological studies indicated a positive association between air pollution and autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, cognitive impairment, and decreased corpus callosum (CC) volumes in children [100][101][102]. Evidence shows that (ultra)fine particle exposure during pregnancy induces neurodevelopmental abnormalities in fetuses or offspring [21][77]. Developmental exposure during the critical window of CNS development, equivalent to human first and second trimesters, produced a range of adverse neurodevelopmental disorders, including male-predominant behavioral neurotoxicity and glial activation, ventriculomegaly, depressive behaviors, impaired contextual memory, and reduced food-seeking behavior [78][79][91][103]. Prenatal air pollution exposure caused hippocampal vascular leakage and impaired neurogenesis, which was associated with behavioral deficits [78]. In utero exposure to PM2.5 (6 h/day, 5 days/week) altered the neuroimmune phenotype [79]. Gestational DEP exposure caused cellular and axonal hypertrophies in olfactory tissues and affected monoaminergic neurotransmission in fetal olfactory bulbs, leading to altered olfactory-based behaviors [80]. Pregnant mice were exposed 6 h/day to concentrated ambient fine/ultrafine particles at the average concentration of 92.69 μg/m3 during GD1–GD17 to recognize the critical window of neurodevelopmental disorders. Such exposure induced ventriculomegaly, increased the CC area, and decreased the hippocampal area in both sexes of offspring. Meanwhile, both sexes exhibited CC hypermyelination, increased microglial activation, and decreased total CC microglia. Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are the main mechanisms of CNS toxicity induced by ambient ultrafine particles during gestation [91]. Exposure to fine and ultrafine particles during the fetal period alters postnatal oligodendrocyte maturation, proliferation capacity, and myelination [103].

Carbon-based nanomaterials. Intratracheal instillation, intranasal instillation, and airway exposure were often adopted to evaluate neurodevelopmental disorders induced by CB NPs. Maternal inhalation exposures to CB NPs triggered habituation pattern and brain blood vessel alteration, dysregulated gene expression in the frontal cortex, and reactive astrogliosis in fetal brains [22][82][83][84]. For example, the intranasal administration of CB NPs (2.9, 15, and 73 μg/kg) into pregnant ICR mice on GD5 and GD9 induced dose-dependent reactive astrogliosis in offspring brains, indicating the increased risk of age-related neurodegenerative diseases onset. Maternal inhalation exposure to CB NPs induced dose-dependent reactive astrogliosis in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, and an increase in the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) protein level in astrocytes of the offspring brain [22]. After maternal exposure to CB NPs, C57BL/6 J mice were found to have sex- and region-specific pathological abnormalities in the CC and cortex with a significant increase in the GFAP protein level [84]. After the intravenous injection of MWCNTs functionalized with 1, 2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (PL-PEG-NH2), larger-sized MWCNTs moved across the blood–placenta barrier (BPB), restricted the development of fetuses, and induced brain deformity, whereas SWCNT and smaller-sized MWCNTs showed no or less fetotoxicity. Furthermore, p53-/- fetuses showed obvious brain deformity, indicating that CNTs might have a genetic background-dependent toxic effect on the normal development of the embryo [70].

Metal oxide NPs and Metal NPs. Gestational exposure to metal oxide led to the accumulation of NPs in the fetal brain, causing neurotoxicity and neurobehaviors associated with enhanced depression-like behaviors, impaired learning and memory, and autism spectrum disorder in offspring [19][23][74][85][86][87][88][89]. For example, oral exposure to ZrO2 NPs during gestation caused their accumulation of fetal brain; hence, they were dangerous to fetal brain development, especially in early pregnancy [18]. Continuously intragastric feeding of TiO2 NPs (6.5 nm) to mice from prenatal day 7 to postnatal day (PND) 21 led to brain retardation, retarded axonal and dendritic outgrowth, and impaired cognitive ability; it was related to the excessive activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2/MAPK) signaling pathway [19]. The subcutaneous injection of TiO2 NPs into pregnant mice altered the expression levels of genes related to CNS development and function [23]. Exposures to ZnO NPs during gestation also induced neurobehavioral abnormalities, such as impaired learning and memory ability, depression-like behaviors, and adverse effects on reflexive motor behavior. The exposure of pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats to ZnO NPs (500 mg/kg) via gavage for 18 consecutive days significantly elevated the concentration of zinc in offspring brains. Abnormal neuron ultrastructure, histopathologic changes, and imbalanced antioxidant status were observed in offspring brains, impairing learning and memory ability in adulthood [85]. Recently, Hawkins et al. reported that maternal exposure to metal NPs induced autophagy-induced developmental neurotoxicity. In this study, the intravenous injection of cobalt and chromium (CoCr) NPs (0.12 mg/mouse) into pregnant mice on GD10 or GD13 resulted in neurodevelopmental abnormalities, such as reactive astrogliosis and aggravated DNA damage, in the fetal hippocampus [21].

NP-induced neurotoxicity depends on the physicochemical parameters of NPs, pregnancy stages, and administration procedures. The dissolution of NPs (i.e., Ag NPs or ZnO NPs) plays an important role in fetotoxicity after maternal exposure.

2.3. Reproductive Toxicity

Regarding the reproductive toxicity, reproductive dysfunction in male offspring after maternal exposure to NPs has been reported (Table 3).

Table 3. NP-induced reproductive toxicity following maternal exposure during pregnancy.

|

NPs |

Animals/Exposure Route |

Fetotoxicities |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

CB NPs 14 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 200 μg/kg, GD8, GD15 |

Alteration in reproductive function of male offspring |

[25] |

|

CB NPs 14 nm; |

Mouse, intratracheal instillation, 268 μg/mouse, GD7, 10, 15 and 18 |

Lowered sperm production |

[28] |

|

TiO2 NPs 21 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 42 mg/m3, 1 h/day, 840 μg/mouse, GD8–GD18 |

Lowered sperm production |

[28] |

|

SiO2 NPs ZnO NPs |

Mouse, i.g., ZnO NPs: 0,50,100,300 mg/kg, SiO2 NPs: 0,50,250 mg/kg, GD15–GD19 |

Prominent epithelial vacuolization, decreased seminiferous tubule diameter in testis |

[59] |

|

PEI-NPs 28 nm PAA-NPs 30 nm |

Mouse, i.p., 10, 100 mg/kg, GD9, 10 and 11 |

charge-dependent fetal loss, morphological alterations in uteri and testes of offspring |

[60] |

|

Asian sand dust |

Mouse, intratracheal instillation, 200 μg/mouse, GD8 and 15 |

Partial vacuolation of seminiferous tubules and low DSP in immature offspring |

[104] |

|

Nanoparticle-rich DE |

Rat, inhalation exposure, 148.86 g/m3, 1.83 × 106 particles/cm3, GD2–GD20 |

Endocrine disruption after birth and suppression in testicular function |

[105] |

|

TiO2 NPs 35 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 0.5, 5, 50, 500 μg/mouse, GD5, 8, 11, 14 and 17 |

A dose-dependent increase in the number of agglomerates in the offspring testes |

[106] |

|

TiO2 NPs 25–70 nm |

Mouse, s.c., 1 mg/mL, 100 μL, GD3, 7, 10 and 14 |

Decreased daily sperm production in offspring |

[107] |

Abbreviations: GD, gestational day; i.g., intragastrical; i.p., intraperitoneal; s.c., subcutaneous; Ref., references; DSP, daily sperm production.

Ambient fine or ultrafine particles. The intratracheal administration of Asian sand dust (ASD, 0.91–1.7 μm, 200 μg/mouse) on GD8 and GD15 into pregnant ICR mice induced significantly decreased testis and epididymis weight in offspring. Pathological alterations included the vacuolation of seminiferous tubules and cellular adhesion of seminiferous epithelia, which resulted in significantly decreased daily sperm production (DSP) in offspring [104]. Gestational exposure to DEPs disrupted testicular function and affected gonadal development in offspring, which included decreased seminal vesicle and prostate coefficients, loss of germ cells in seminiferous tubules, and increased DNA fragmentation rate of sperm [105][108].

Carbon-based nanomaterials. Most in vivo findings indicated that in utero exposure to CB NPs and MWCNTs might affect the reproductive system and function in male/female offspring [22][70][82][83][84]. CB NP-induced male reproductive disorders depended on different administration routes and doses. In detail, after pregnant mice were intratracheally instilled with CB NPs (200 μg/mouse, 14 nm) on GD8 and GD15, partially vacuolated seminiferous tubules and reduced cellular adhesion in seminiferous epithelia were observed 5, 10, and 15 weeks after birth, with DSP significantly decreased by 47%, 34%, and 32%, respectively [25]. Similar reduced DSP appeared in the second generation (F2) after prenatal exposure to CB NPs (200 μg/mouse) on GD7, 10, 15, and 18 [28]. However, maternal inhalation of CB NPs at occupationally relevant concentrations did not change male reproductive function even in four generations of offspring mice [24]. Treatment with MWCNTs and graphene quantum dots also did not induce alterations in the DSP and male reproductive ability of the exposed male offspring [27][71].

Metal oxide NPs. Previous investigations indicated that in utero exposure to ZnO NPs, TiO2 NPs, Fe2O3 NPs, and SiO2 NPs affected male reproductive ability and the reproductive function of offspring [28][59][60][106][107]. The subcutaneous injection of TiO2 NPs into pregnant mice resulted in alterations in spermatogenesis and impairment in the testis of offspring. TiO2 NPs were transferred to the offspring and accumulated in Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, or spermatids of offspring testes, leading to reduced DSP and the number of Sertoli cells, disorganized and disrupted seminiferous tubules, and failed spermiation from Sertoli cells and sperm motility [106]. In contrast, inhalation exposure to TiO2 NPs during gestation at the total doses of 0.5, 5, 50, and 500 μg did not affect the male reproductive function in two generations of male offspring mice [28]. The oral administration of ZnO NPs (50 and 100 mg/kg) and SiO2 NPs (250 mg/kg) triggered alterations in spermatogenesis and pathological changes in testis, such as epithelial vacuolization, cellular adhesion of epithelia, and decreased seminiferous tubule diameter [59]. Similarly, Di Bona et al. reported a charge- and dose-dependent effect on the reproduction of offspring by prenatal exposure to Fe2O3 NPs. Polyethyleneimine Fe2O3 NPs(+) treatment induced morphological alterations in offspring uteri and testis during organogenesis, while poly(acrylic acid) Fe2O3 NPs(−) treatment only induced mild alterations in the offspring uterine cavity [60]. The aforementioned data demonstrated that not only the accumulation of NPs in reproductive tissues but also the reproductive toxicity induced in offspring depended on administration routes, doses, exposure windows, and particle charge.

2.4. Immunotoxicity

The innate immune system of an organism provides the first line of defense against particulate materials. Pregnant women and developing fetuses are populations susceptible to immunotoxicity induced by xenobiotic pollutants. Developmental immunotoxicity induced by various NPs in mice is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. NP-induced immunotoxicity following maternal exposure during pregnancy.

|

NPs |

Animals/Exposure Route |

Fetotoxicities |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PMs |

Mouse, oropharyngeal aspiration, 3 mg/kg, GD10, and 17 |

Inhibition of the development of pulmonary T helper and T regulatory cells of the infant offspring |

[29] |

|

PMs |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 95 μg/kg, GD14, 16, and 18 |

Inhibition of splenic T cell maturation in male offspring and alteration in early life immune development in a sex specific manner |

[30] |

|

Cu NPs |

Mouse, inhalation exposure, 3.5 mg/m3, 4 h/day, GD4–GD20 |

Altered expression of several Th1/Th2 or other immune response genes in pups’ spleens |

[31] |

|

CB NPs 14 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 95 μg/kg, GD9 and 15 |

Allergic or inflammatory effects in male offspring |

[32] |

|

PM2.5 |

Moue, inhalation exposure, 8 h/day, 6 days/week, 16 weeks |

Alteration in immune microenvironment |

[109] |

|

DEPs 14 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 50 μg/mouse, GD14 |

Increased allergic susceptibility in offspring |

[110] |

|

CB NPs 14 nm |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 95 μg/kg, GD9 and 15 |

Suppressed development of immune system of the offspring mice |

[111] |

|

DEPs |

Mouse, i.g., 31.25, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 mg/kg, GD11–GD16 |

Increase in the frequency of DNA deletions in the mouse fetus and such genetic alterations in the offspring |

[69] |

|

DEPs |

Mouse, intranasal instillation, 50 μg/mouse, GD14–GD15 |

Triggered transgenerational transmission of asthma risk |

[112] |

Abbreviations: GD, gestational day; i.g., intragastrical; Ref., references; PM, particulate matter.

Ambient fine or ultrafine particles. In recent years, detrimental effects on the immune development of the offspring after maternal exposures to PM have received more attention [29][30][109]. After maternal exposure to ultrafine particles derived from combustion (containing persistent free radicals) via oropharyngeal aspiration on GD 10 and 17, the development of pulmonary T helper and T regulatory cells was suppressed in the infant offspring at the age of 6 days. At the age of 6 weeks, the percentage of Th2 and T regulatory cells recovered to the control levels, while the percentage of Th1 and Th17 cells decreased. Maternal exposure to combustion-derived ultrafine particles aggravated postnatal asthma severity, in association with the suppression of pulmonary Th1 development and systemic oxidative stress in exposed mothers [29]. The intranasal administration of community-sampled PM into pregnant C57BL/6 mice on GD14, GD16, and GD18 altered the immune cell development of offspring mice in a sex-specific manner [30]. Furthermore, pregnant BALB/c mice intranasally instilled with DE on GD14 caused increased asthma susceptibility or transgenerationally transmitted asthma susceptibility in offspring [110].

Carbon-based Nanomaterials and Metal NPs. El-Sayed et al. reported the adverse effects on the immune system of offspring after gestational exposure to CB NPs [32][111]. After pregnant ICR mice were instilled intranasally with CB NPs (14 nm, 95 μg/kg) on GD9 and GD15, CB NPs triggered alterations in thymocyte and splenocyte phenotypes, and upregulated Traf6 gene expression in the thymus. Therefore, respiratory exposure to CB NPs in middle and late gestation might cause allergic or inflammatory effects in male offspring mice [32]. When exposure occurred during early gestation, CB NPs suppressed the development of the offspring immune system partially, as characterized by decreased numbers of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells, and upregulated Il15 (in male offspring), Ccr7 and Ccl19 (in female offspring) gene expression [111]. In one study investigating the developmental immunotoxicity induced by metal NPs in offspring, pregnant C57BL/6 mice were exposed to Cu NPs (15.7 nm, 3.5 mg/m3) via inhalation from GD3–GD19 [31]. Among 84 genes involved in T cell immune responses in spleens of pups, 14 genes were significantly upregulated and 11 genes were significantly downregulated at the age of 7 weeks, indicating that prenatal inhalation exposure induced significant immunomodulatory effects in offspring. Despite no translocation of NPs into the fetus, Cu NPs induced maternal pulmonary inflammation, subsequently leading to the disruption of the Th1/Th2 balance in the developing fetus.

2.5. Respiratory Toxicity

Epidemiological studies have proved that maternal exposure to ambient PMs during the gestational period is associated with disturbed lung development and increased risk of respiratory diseases after birth. So far, investigations have mostly focused on PMs; only a few have explored metal oxide NPs and metal NPs.

Ambient fine or ultrafine particles. The exposure of pregnant C57/BL6 mice to combustion-derived PMs via oropharyngeal aspiration aggravated asthma development in offspring mice [29]. This aggravation of asthma in offspring might be due to systemic oxidative damage in exposed mothers and Th1 maturation in offspring lungs. In utero exposure to PMs from residential roof spaces induced impairment in somatic growth, leading to reduced lung volume and dysfunction of male offspring lungs [30]. Yue et al. reported that increased inflammation in the respiratory system of the fetus and offspring was observed after maternal exposure to PM2.5 (3 mg/kg) by oropharyngeal aspiration every other day from GD1–GD17 [34].

Metal NPs and Metal oxide NPs. Maternal exposure to metallic NPs during pregnancy, such as TiO2 NPs, CeO2 NPs, and Ag NPs, might lead to the transfer of NPs from the mother to the fetal lung and induce impairment in lung development and even a lasting effect in adulthood [35][113]. For example, NPs translocated across the placental barrier and deposited in the offspring lungs after the mice were orally exposed to TiO2 NPs (21 nm) daily for 7 days during pregnancy [113]. The exposure induced delayed saccular development and inflammatory lesions in offspring lungs, accompanied by deficient septation, thickened mesenchyme between the saccules, atypical lamellar inclusions, macrophage infiltration, and thickened primary septa. In another study, the exposure of TiO2 NPs, CeO2 NPs, and Ag NPs resulted in irreversible impairment in offspring lungs regardless of the chemical properties of NPs with alterations in lung development-related genes and proteins in the fetal and alveolarization stages [35].

In summary, the aforementioned results provided a comprehensive understanding on how the key parameters of particles affected NP-induced fetotoxicity, including neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, developmental immunotoxicity, and respiratory toxicity, in offspring (Figure 2). However, the evaluation of fetotoxicity in other organs such as the liver, and cardiac function, feto-placental development, microvascular function, and fetal metabolism need further investigation.

Figure 2. Typical fetotoxicity potentially induced by various NPs. The properties of NPs such as size, shape, composition and surface chemistry are key parameters that affect fetotoxicity following maternal exposure NPs during pregnancy. In addition, maternal conditions and exposure routes, also play crucial roles in NP-induced fetotoxicity.

3. Transplacental Transfer of NPs

The placenta is a vital organ connecting the mother and the fetus in mammals. During gestation, the placenta not only is the site for the exchange of substances, metabolism, secretion, and excretion, but also protects the embryo/fetus from the harmful environmental pollutants. Although anatomical differences in the placenta exist among species, the most commonly selected models used to explore transplacental transfer ability and fetotoxicity are human and murine placenta models. Different from human term placenta, the mature murine placenta consists of three trophoblast layers, including the decidua, junctional zone, and labyrinth, constituting the primary barrier [114][115][116]. Any structural and functional abnormalities in the placenta may impair its barrier function and affect fetal development. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of placental transfer and transplacental transport mechanisms is of great significance. The following section briefly discussed the maternal–fetal transfer of NPs and the underlying transport mechanisms.

4. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in NP-Induced Fetotoxicity

Maternal NP exposure may induce fetotoxicity by the direct translocation of NPs to the fetus or indirect NP-induced maternal and placental mediators [37][38][117]. During the critical window of fetal development, the factors interfering with the whole process of gestation (maternal condition, placental function, and developing fetus), contribute to detrimental fetal outcomes. This section discussed different molecular mechanisms involved in NP-induced developmental toxicity.

4.1. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Responses

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and inflammatory responses are generally considered as the main mechanisms in NP-induced fetotoxicity [118]. First, this may occur when NPs enter into maternal or fetal tissues. For example, prenatal exposure to CB NPs, and TiO2 NPs during pregnancy triggered oxidative damage to nucleic acids and lipids, and induced reactive astrocytes via the overexpression of GFAP and Aquaporin 4 (Aqp4) in offspring brain [22][84]. Inhaled NPs localized in the lungs could generate ROS and inflammatory responses, which became a potent maternal modulator for fetal development. Prenatal exposure to TiO2 NPs (21 nm, 40 mg/m3) 1h/day from GD8–GD18 induced the deposition of NPs in lungs and long-term maternal lung inflammation, resulting in a sex-specific neurobehavioral alteration in offspring [74]. Second, the balance between oxidants and antioxidants is vital for maintaining physiological homeostasis in the placenta. Once NPs are taken up by the placental cells, the induction of excessive ROS results in oxidative stress and placental inflammation, which has been hypothesized to represent one indirect mechanistic pathway of NP-induced placental dysfunction and fetotoxicity. The intravenous injection of SiO2 NPs (70 nm, 0.04 mg/g) into pregnant mice from GD13–GD14 upregulated nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and significantly increased the levels of placental inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL2) [64]. This exposure during gestation triggered NLRP3-mediated placental inflammation and placental dysfunction due to ROS generation and oxidative stress, resulting in pregnancy-related complications. Increased ROS levels in malformed fetuses and their placentas were observed following the retrobulbar injection of uo-SWCNTs from GD6 [17]. After pregnant mice were intravenously injected with o-SWCNTs (20 mg/kg), increased levels of ROS and decreased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) led to narrowed vessels and decreased blood vessels in the placenta, which induced miscarriage and fetal growth retardation [65]. Maternal exposure to other NPs such as SiO2 NPs, SWCNTs, and TiO2 NPs, induced oxidative stress and a high incidence of detrimental developmental outcomes [17][64][89]. These results proved the involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation in NP-induced fetotoxicity.

4.2. DNA Damage

DNA damage is generally thought to be responsible for initiating fetal developmental abnormalities caused by environmental chemicals. Maternal exposure to NPs during pregnancy may cause severe DNA damage, such as DNA strand breaks, DNA deletions, mutations and oxidative DNA adducts. SWCNT-50 can induce p53-dependent fetotoxicity and brain deformity in p53-/- fetuses, which is related to MWCNT 50-induced DNA damage [70]. Maternal inhalation exposure to CB NPs (42 mg/kg, 1h/day) from GD8–GD18 caused DNA strand breaks in the exposed offspring, while prenatal TiO2 NPs exposure altered the gene expression of the retinoic acid signaling pathway in female rather than male mice [43][119]. Transplacental Au NP exposure (100 nm, 3.3 mg/kg) during organogenesis indicated size-dependent clastogenic and epigenetic alterations in fetuses, while transplacental DEP exposure caused DNA deletions [69][120]. Maternal NP exposure to CoCr NPs aggravated DNA damage in the fetal hippocampus through autophagy dysfunction and the release of IL-6 [21].

4.3. Apotosis

Maternal exposure to SiO2 NPs, TiO2 NPs, Au NPs, QDs, functionalized CNTs, and carboxylate-modified polystyrene beads during pregnancy induced cell apoptosis in spongiotrophoblasts of the placenta [15][16][121][122][123], the fetal hippocampus [19][23][92][93], and fetal liver [70][124][125], which led to placental dysfunction and poor developmental outcomes.

For example, gestational exposure to TiO2 NPs (<25 nm) via gavage from GD1–GD13 triggered apoptosis, dysregulated vascularization, and proliferation, which significantly impaired placental growth and development [123]. In addition, TiO2 NPs suppressed axonal or dendritic outgrowth, through the induction of apoptosis in the offspring hippocampus [19][23][92][93][107]. Similarly, apoptosis was also observed in the 6-week offspring brains following maternal exposure to ultrafine CB [126]. In another study, functionalized MWCNTs directly triggered p53-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through DNA damage, suggesting genetic background-dependent developmental abnormalities [70]. Carboxylate-modified polystyrene beads can pass through the placenta into fetal organs, and induced trophoblast apoptosis [122]. Other nanomaterials, including SiO2 NPs, ZrO2 NPs, and Au NPs likewise induced pathological and structural alterations in apoptosis and apoptosis-related factors in the placenta following gestational NP exposure [16][18][65][121].

4.4. Autophagy

NP-induced autophagy has been widely reported [127][128]. For example, both MWCNTs and two-dimensional MoS2 nanosheets induced autophagy relying on the variation in surface chemistry and shape [128][129][130]. Throughout pregnancy, autophagy is involved in oocytogenesis [131], implantation [132], placentation [133][134], embryogenesis [135][136], preeclampsia [133][137] and preterm delivery [138]. Especially during placental development, autophagy, mediated by alterations in oxygen and glucose levels in cytotrophoblast cells, participates in placentation and placental-related diseases, ultimately affecting fetal development. Some studies demonstrated that autophagy might alleviate the toxicity of platinum NPs in trophoblasts [139] and protect the fetal brain under short-term food deprivation [140]. However, autophagic dysfunction in the placenta is associated with fetal diseases such as fetal growth retardation and neonatal encephalopathy [141]. CoCr NPs induced autophagic dysfunction in BeWo cell barriers, contributing to the altered differentiation of human neural progenitor cells and DNA damage in the derived neurons and astrocytes [21]. TiO2 NPs induced autophagy and possible placental dysfunction in HTR-8/SVneo cells through the activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress [142][143]. MiR-96-5p and miR-101-3p might act as potential targets to reverse autophagy and placenta dysfunction induced by TiO2 NPs in a human trophoblast model [143]. In addition, abnormal autophagy disrupted organism development and differentiation during embryogenesis. Zhou et al. demonstrated that maternal exposure to TiO2 NPs induced excessive autophagy with significant enhancement in expression levels of autophagy-related factors and LC3 II/LC3I, resulting in the severe suppression of dendritic outgrowth in offspring hippocampal neurons [93].

The aforementioned studies revealed that NPs might disrupt placental development and embryo–fetal development via autophagy. The placenta acted as a vital support unit for the developing fetus and played a pivotal role in regulating fetal development such as fetal brain [144]. Therefore, placental dysfunction mediated by autophagy and its molecular events might be one of the mechanisms underlying NP-induced fetal developmental abnormalities. Considering its two-way regulation and limited data regarding autophagy in the placenta, further studies should be conducted to explore the role of autophagy in NP-induced fetotoxicity.

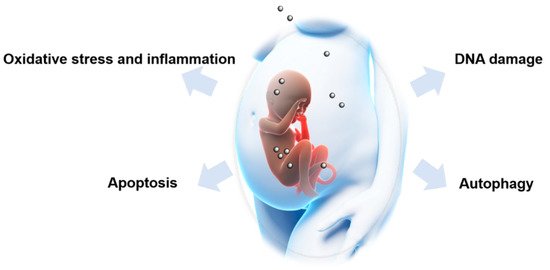

In addition, NPs may induce fetotoxicity via interfering with endocrine signaling [145][146], vascular signaling [16][56][147], placental Toll-like receptors [148], and other cellular signaling pathways. The major underlying molecular mechanisms involved in NP-induced fetotoxicity are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Possible mechanisms involved in nanoparticle-induced fetotoxicity. Oxidative stress and inflammation, DNA damage, apoptosis and autophagy are major mechanisms underlying nanoparticle-induced fetotoxicity.

References

- Petros, R.A.; DeSimone, J.M. Strategies in the design of nanoparticles for therapeutic applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 615–627.

- Bowman, D.M.; Van Calster, G.; Friedrichs, S. Nanomaterials and regulation of cosmetics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 92.

- Konstantatos, G.; Sargent, E.H. Nanostructured materials for photon detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 391–400.

- Jia, J.; Li, F.; Zhai, S.; Zhou, H.; Liu, S.; Jiang, G.; Yan, B. Susceptibility of overweight mice to liver injury as a result of the ZnO nanoparticle-enhanced liver deposition of Pb2+. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1775–1784.

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, B. Nanotoxicity overview: Nano-threat to susceptible populations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 3671–3697.

- Jia, J.; Li, F.; Zhou, H.; Bai, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Yan, B. Oral exposure to silver nanoparticles or silver ions may aggravate fatty liver disease in overweight Mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 9334–9343.

- Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, B. Aggravated hepatotoxicity occurs in aged mice but not in young mice after oral exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles. NanoImpact 2016, 3–4, 1–11.

- Luyten, L.J.; Saenen, N.D.; Janssen, B.G.; Vrijens, K.; Plusquin, M.; Roels, H.A.; Debacq-Chainiaux, F.; Nawrot, T.S. Air pollution and the fetal origin of disease: A systematic review of the molecular signatures of air pollution exposure in human placenta. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 310–323.

- Barker, D.J. Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 1995, 311, 171–174.

- Zhong, H.; Geng, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, R.; Yu, C.; Yang, Z.; Chen, X.; Mu, X.; Liu, X.; He, J. Maternal exposure to CeO2 NPs during early pregnancy impairs pregnancy by inducing placental abnormalities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 1–10.

- Teng, C.; Jia, J.; Wang, Z.; Yan, B. Oral co-exposures to zinc oxide nanoparticles and CdCl2 induced maternal-fetal pollutant transfer and embryotoxicity by damaging placental barriers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 189, 109956.

- Morales-Rubio, R.A.; Alvarado-Cruz, I.; Manzano-Leon, N.; Andrade-Oliva, M.D.; Uribe-Ramirez, M.; Quintanilla-Vega, B.; Osornio-Vargas, A.; De Vizcaya-Ruiz, A. In utero exposure to ultrafine particles promotes placental stress-induced programming of renin-angiotensin system-related elements in the offspring results in altered blood pressure in adult mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 7.

- Yang, L.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wei, H.; Xu, H. Quantum dots cause acute systemic toxicity in lactating rats and growth restriction of offspring. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11564–11577.

- Campagnolo, L.; Massimiani, M.; Vecchione, L.; Piccirilli, D.; Toschi, N.; Magrini, A.; Bonanno, E.; Scimeca, M.; Castagnozzi, L.; Buonanno, G.; et al. Silver nanoparticles inhaled during pregnancy reach and affect the placenta and the foetus. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 687–698.

- Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Kuang, H.; Yang, P.; Aguilar, Z.P.; Wang, A.; Fu, F.; Xu, H. Acute toxicity of quantum dots on late pregnancy mice: Effects of nanoscale size and surface coating. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 318, 61–69.

- Yamashita, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Higashisaka, K.; Mimura, K.; Morishita, Y.; Nozaki, M.; Yoshida, T.; Ogura, T.; Nabeshi, H.; Nagano, K.; et al. Silica and titanium dioxide nanoparticles cause pregnancy complications in mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 321–328.

- Pietroiusti, A.; Massimiani, M.; Fenoglio, I.; Colonna, M.; Valentini, F.; Palleschi, G.; Camaioni, A.; Magrini, A.; Siracusa, G.; Bergamaschi, A.; et al. Low doses of pristine and oxidized single-wall carbon nanotubes affect mammalian embryonic development. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4624–4633.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, B. Breakthrough of ZrO2 nanoparticles into fetal brains depends on developmental stage of maternal placental barrier and fetal blood-brain-barrier. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 1–11.

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, J.; Chen, C.; Hong, F. Retardation of axonal and dendritic outgrowth is associated with the MAPK signaling pathway in offspring mice following maternal exposure to nanosized titanium dioxide. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2019, 67, 2709–2715.

- Morris-Schaffer, K.; Merrill, A.K.; Wong, C.; Jew, K.; Sobolewski, M.; Cory-Slechta, D.A. Limited developmental neurotoxicity from neonatal inhalation exposure to diesel exhaust particles in C57BL/6 mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 1.

- Hawkins, S.J.; Crompton, L.A.; Sood, A.; Saunders, M.; Boyle, N.T.; Buckley, A.; Minogue, A.M.; McComish, S.F.; Jimenez-Moreno, N.; Cordero-Llana, O.; et al. Nanoparticle-induced neuronal toxicity across placental barriers is mediated by autophagy and dependent on astrocytes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 427–433.

- Onoda, A.; Takeda, K.; Umezawa, M. Dose-dependent induction of astrocyte activation and reactive astrogliosis in mouse brain following maternal exposure to carbon black nanoparticle. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2017, 14, 4.

- Shimizu, M.; Tainaka, H.; Oba, T.; Mizuo, K.; Umezawa, M.; Takeda, K. Maternal exposure to nanoparticulate titanium dioxide during the prenatal period alters gene expression related to brain development in the mouse. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009, 6, 20.

- Skovmand, A.; Jensen, A.C.O.; Maurice, C.; Marchetti, F.; Lauvas, A.J.; Koponen, I.K.; Jensen, K.A.; Goericke-Pesch, S.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K.S. Effects of maternal inhalation of carbon black nanoparticles on reproductive and fertility parameters in a four-generation study of male mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 13.

- Yoshida, S.; Hiyoshi, K.; Oshio, S.; Takano, H.; Takeda, K.; Ichinose, T. Effects of fetal exposure to carbon nanoparticles on reproductive function in male offspring. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 1695–1699.

- Johansson, H.K.L.; Hansen, J.S.; Elfving, B.; Lund, S.P.; Kyjovska, Z.O.; Loft, S.; Barfod, K.K.; Jackson, P.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K.S. Airway exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes disrupts the female reproductive cycle without affecting pregnancy outcomes in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2017, 14, 17.

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fu, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Chu, M. Systematic evaluation of graphene quantum dot toxicity to male mouse sexual behaviors, reproductive and offspring health. Biomaterials 2019, 194, 215–232.

- Kyjovska, Z.O.; Boisen, A.M.; Jackson, P.; Wallin, H.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K.S. Daily sperm production: Application in studies of prenatal exposure to nanoparticles in mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 36, 88–97.

- Wang, P.; You, D.; Saravia, J.; Shen, H.; Cormier, S.A. Maternal exposure to combustion generated PM inhibits pulmonary Th1 maturation and concomitantly enhances postnatal asthma development in offspring. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 29.

- Chen, L.; Bennett, E.; Wheeler, A.J.; Lyons, A.B.; Woods, G.M.; Johnston, F.; Zosky, G.R. Maternal exposure to particulate matter alters early post-natal lung function and immune cell development. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 625–635.

- Adamcakova-Dodd, A.; Monick, M.M.; Powers, L.S.; Gibson-Corley, K.N.; Thorne, P.S. Effects of prenatal inhalation exposure to copper nanoparticles on murine dams and offspring. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 12, 30.

- El-Sayed, Y.S.; Shimizu, R.; Onoda, A.; Takeda, K.; Umezawa, M. Carbon black nanoparticle exposure during middle and late fetal development induces immune activation in male offspring mice. Toxicology 2015, 327, 53–61.

- Yue, H.; Ji, X.; Li, G.; Hu, M.; Sang, N. Maternal exposure to PM2.5 affects fetal lung development at sensitive windows. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 316–324.

- Yue, H.; Ji, X.; Ku, T.; Li, G.; Sang, N. Sex difference in bronchopulmonary dysplasia of offspring in response to maternal PM2.5 exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 389, 122033.

- Paul, E.; Franco-Montoya, M.L.; Paineau, E.; Angeletti, B.; Vibhushan, S.; Ridoux, A.; Tiendrebeogo, A.; Salome, M.; Hesse, B.; Vantelon, D.; et al. Pulmonary exposure to metallic nanomaterials during pregnancy irreversibly impairs lung development of the offspring. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 484–495.

- Bove, H.; Bongaerts, E.; Slenders, E.; Bijnens, E.M.; Saenen, N.D.; Gyselaers, W.; Van Eyken, P.; Plusquin, M.; Roeffaers, M.B.J.; Ameloot, M.; et al. Ambient black carbon particles reach the fetal side of human placenta. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3866.

- Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Schaepper, K.; Aengenheister, L.; Wick, P. Developmental toxicity of nanomaterials: Need for a better understanding of indirect effects. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2018, 31, 641–642.

- Dugershaw, B.B.; Aengenheister, L.; Hansen, S.S.K.; Hougaard, K.S.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T. Recent insights on indirect mechanisms in developmental toxicity of nanomaterials. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 31.

- Manangama, G.; Audignon-Durand, S.; Migault, L.; Gramond, C.; Zaros, C.; Teysseire, R.; Sentilhes, L.; Brochard, P.; Lacourt, A.; Delva, F. Maternal occupational exposure to carbonaceous nanoscale particles and small for gestational age and the evolution of head circumference in the French Longitudinal Study of Children—Elfe study. Environ. Res. 2020, 185, 109394.

- Manangama, G.; Migault, L.; Audignon-Durand, S.; Gramond, C.; Zaros, C.; Bouvier, G.; Brochard, P.; Sentilhes, L.; Lacourt, A.; Delva, F. Maternal occupational exposures to nanoscale particles and small for gestational age outcome in the French Longitudinal Study of Children. Environ. Int. 2019, 122, 322–329.

- Valentino, S.A.; Tarrade, A.; Aioun, J.; Mourier, E.; Richard, C.; Dahirel, M.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D.; Fournier, N.; Aubriere, M.C.; Lallemand, M.S.; et al. Maternal exposure to diluted diesel engine exhaust alters placental function and induces intergenerational effects in rabbits. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 39.

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Suzuki, A.K.; Zhang, Y.; Fujitani, Y.; Nagaoka, K.; Watanabe, G.; Taya, K. Effects of exposure to nanoparticle-rich diesel exhaust on pregnancy in rats. J. Reprod. Dev. 2013, 59, 145–150.

- Jackson, P.; Hougaard, K.S.; Boisen, A.M.; Jacobsen, N.R.; Jensen, K.A.; Moller, P.; Brunborg, G.; Gutzkow, K.B.; Andersen, O.; Loft, S.; et al. Pulmonary exposure to carbon black by inhalation or instillation in pregnant mice: Effects on liver DNA strand breaks in dams and offspring. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 486–500.

- Fujitani, T.; Ohyama, K.-I.; Hirose, A.; Nishimura, T.; Nakae, D.; Ogata, A. Teratogenicity of multi-wall carbon nanotube (MWCNT) in ICR mice. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 37, 81–89.

- Vidanapathirana, A.K.; Thompson, L.C.; Odom, J.; Holland, N.A.; Sumner, S.J.; Fennell, T.R.; Brown, J.M.; Wingard, C.J. Vascular tissue contractility changes following late gestational exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes or their dispersing vehicle in Sprague Dawley rats. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5.

- Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, M. Long-term toxicity of reduced graphene oxide nanosheets: Effects on female mouse reproductive ability and offspring development. Biomaterials 2015, 54, 188–200.

- Chen, B.; Hong, W.; Yang, P.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Aguilar, Z.P.; Xu, H. Nano zinc oxide induced fetal mice growth restriction, based on oxide stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 259.

- Teng, C.; Jia, J.; Wang, Z.; Sharma, V.K.; Yan, B. Size-dependent maternal-fetal transfer and fetal developmental toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles after oral exposures in pregnant mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109439.

- Lee, J.; Yu, W.J.; Song, J.; Sung, C.; Jeong, E.J.; Han, J.S.; Kim, P.; Jo, E.; Eom, I.; Kim, H.M.; et al. Developmental toxicity of intravenously injected zinc oxide nanoparticles in rats. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2016, 39, 1682–1692.

- Hong, J.S.; Park, M.K.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, J.H.; Park, G.J.; Maeng, E.H.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, M.K.; Jeong, J.; Park, J.A.; et al. Prenatal development toxicity study of zinc oxide nanoparticles in rats. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 159–171.

- Jo, E.; Seo, G.; Kwon, J.-T.; Lee, M.; Lee, B.C.; Eom, I.; Kim, P.; Choi, K. Exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles affects reproductive development and biodistribution in offspring rats. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 38, 525–530.

- Bowdridge, E.C.; Abukabda, A.B.; Engles, K.J.; McBride, C.R.; Batchelor, T.P.; Goldsmith, W.T.; Garner, K.L.; Friend, S.; Nurkiewicz, T.R. Maternal engineered nanomaterial inhalation during gestation disrupts vascular kisspeptin reactivity. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 169, 524–533.

- Hong, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sheng, L.; Wang, L. Maternal exposure to nanosized titanium dioxide suppresses embryonic development in mice. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 6197–6204.

- Pietroiusti, A.; Vecchione, L.; Malvindi, M.A.; Aru, C.; Massimiani, M.; Camaioni, A.; Magrini, A.; Bernardini, R.; Sabella, S.; Pompa, P.P.; et al. Relevance to investigate different stages of pregnancy to highlight toxic effects of nanoparticles: The example of silica. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 342, 60–68.

- Blum, J.L.; Xiong, J.Q.; Hoffman, C.; Zelikoff, J.T. Cadmium associated with inhaled cadmium oxide nanoparticles impacts fetal and neonatal development and growth. Toxicol. Sci. 2012, 126, 478–486.

- Vidanapathirana, A.K.; Thompson, L.C.; Herco, M.; Odom, J.; Sumner, S.J.; Fennell, T.R.; Brown, J.M.; Wingard, C.J. Acute intravenous exposure to silver nanoparticles during pregnancy induces particle size and vehicle dependent changes in vascular tissue contractility in Sprague Dawley rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2018, 75, 10–22.

- Austin, C.A.; Hinkley, G.K.; Mishra, A.R.; Zhang, Q.; Umbreit, T.H.; Betz, M.W.; Wildt, B.E.; Casey, B.J.; Francke-Carroll, S.; Hussain, S.M.; et al. Distribution and accumulation of 10 nm silver nanoparticles in maternal tissues and visceral yolk sac of pregnant mice, and a potential effect on embryo growth. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 654–661.

- Ma, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Jin, S.; Li, S.; Liang, X.-J. Gold nanoparticles cause size-dependent inhibition of embryonic development during murine pregnancy. Nano Res. 2018, 11, 3419–3433.

- Bara, N.; Eshwarmoorthy, M.; Subaharan, K.; Kaul, G. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle is comparatively safer than zinc oxide nanoparticle which can cause profound steroidogenic effects on pregnant mice and male offspring exposed in utero. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2018, 34, 507–524.

- Di Bona, K.R.; Xu, Y.; Gray, M.; Fair, D.; Hayles, H.; Milad, L.; Montes, A.; Sherwood, J.; Bao, Y.; Rasco, J.F. Short- and long-term effects of prenatal exposure to iron oxide nanoparticles: Influence of surface charge and dose on developmental and reproductive toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 30251–30268.

- Stapleton, P.A.; Hathaway, Q.A.; Nichols, C.E.; Abukabda, A.B.; Pinti, M.V.; Shepherd, D.L.; McBride, C.R.; Yi, J.; Castranova, V.C.; Hollander, J.M.; et al. Maternal engineered nanomaterial inhalation during gestation alters the fetal transcriptome. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 3.

- Zalgeviciene, V.; Kulvietis, V.; Bulotiene, D.; Zurauskas, E.; Laurinaviciene, A.; Skripka, A.; Rotomskis, R. Quantum dots mediated embryotoxicity via placental damage. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 73, 222–231.

- Di Bona, K.R.; Xu, Y.; Ramirez, P.A.; DeLaine, J.; Parker, C.; Bao, Y.; Rasco, J.F. Surface charge and dosage dependent potential developmental toxicity and biodistribution of iron oxide nanoparticles in pregnant CD-1 mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2014, 50, 36–42.

- Shirasuna, K.; Usui, F.; Karasawa, T.; Kimura, H.; Kawashima, A.; Mizukami, H.; Ohkuchi, A.; Nishimura, S.; Sagara, J.; Noda, T.; et al. Nanosilica-induced placental inflammation and pregnancy complications: Different roles of the inflammasome components NLRP3 and ASC. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 554–567.

- Qi, W.; Bi, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Wu, W. Damaging effects of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on pregnant mice with different pregnancy times. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4352.

- Campagnolo, L.; Massimiani, M.; Palmieri, G.; Bernardini, R.; Sacchetti, C.; Bergamaschi, A.; Vecchione, L.; Magrini, A.; Bottini, M.; Pietroiusti, A. Biodistribution and toxicity of pegylated single wall carbon nanotubes in pregnant mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 21.

- Philbrook, N.A.; Walker, V.K.; Afrooz, A.R.; Saleh, N.B.; Winn, L.M. Investigating the effects of functionalized carbon nanotubes on reproduction and development in Drosophila melanogaster and CD-1 mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 32, 442–448.

- Philbrook, N.A.; Winn, L.M.; Afrooz, A.R.; Saleh, N.B.; Walker, V.K. The effect of TiO2 and Ag nanoparticles on reproduction and development of Drosophila melanogaster and CD-1 mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 257, 429–436.

- Reliene, R.; Hlavacova, A.; Mahadevan, B.; Baird, W.M.; Schiestl, R.H. Diesel exhaust particles cause increased levels of DNA deletions after transplacental exposure in mice. Mutat. Res. 2005, 570, 245–252.

- Huang, X.; Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Choi, K.Y.; Niu, G.; Zhang, G.; Guo, J.; Lee, S.; Chen, X. The genotype-dependent influence of functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes on fetal development. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 856–865.

- Hougaard, K.S.; Jackson, P.; Kyjovska, Z.O.; Birkedal, R.K.; De Temmerman, P.J.; Brunelli, A.; Verleysen, E.; Madsen, A.M.; Saber, A.T.; Pojana, G.; et al. Effects of lung exposure to carbon nanotubes on female fertility and pregnancy. A study in mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2013, 41, 86–97.

- Lim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, I.-C.; Moon, C.; Kim, S.-H.; Shin, D.-H.; Kim, H.-C.; Kim, J.-C. Evaluation of maternal toxicity in rats exposed to multi-wall carbon nanotubes during pregnancy. Environ. Health Toxicol. 2011, 26, e2011006.

- Lim, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, I.S.; Park, N.H.; Moon, C.; Kang, S.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S.C.; Kim, J.C. Maternal exposure to multi-wall carbon nanotubes does not induce embryo-fetal developmental toxicity in rats. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 92, 69–76.

- Hougaard, K.S.; Jackson, P.; Jensen, K.A.; Sloth, J.J.; Loeschner, K.; Larsen, E.H.; Birkedal, R.K.; Vibenholt, A.; Boisen, A.-M.Z.; Wallin, H.; et al. Effects of prenatal exposure to surface-coated nanosized titanium dioxide (UV-Titan). A study in mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010, 7.

- Guillard, A.; Gaultier, E.; Cartier, C.; Devoille, L.; Noireaux, J.; Chevalier, L.; Morin, M.; Grandin, F.; Lacroix, M.Z.; Coméra, C.; et al. Basal Ti level in the human placenta and meconium and evidence of a materno-foetal transfer of food-grade TiO2 nanoparticles in an ex vivo placental perfusion model. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17.

- Allen, J.L.; Liu, X.; Pelkowski, S.; Palmer, B.; Conrad, K.; Oberdorster, G.; Weston, D.; Mayer-Proschel, M.; Cory-Slechta, D.A. Early postnatal exposure to ultrafine particulate matter air pollution: Persistent ventriculomegaly, neurochemical disruption, and glial activation preferentially in male mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 939–945.

- Allen, J.L.; Conrad, K.; Oberdorster, G.; Johnston, C.J.; Sleezer, B.; Cory-Slechta, D.A. Developmental exposure to concentrated ambient particles and preference for immediate reward in mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 32–38.

- Woodward, N.C.; Haghani, A.; Johnson, R.G.; Hsu, T.M.; Saffari, A.; Sioutas, C.; Kanoski, S.E.; Finch, C.E.; Morgan, T.E. Prenatal and early life exposure to air pollution induced hippocampal vascular leakage and impaired neurogenesis in association with behavioral deficits. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 261.

- Kulas, J.A.; Hettwer, J.V.; Sohrabi, M.; Melvin, J.E.; Manocha, G.D.; Puig, K.L.; Gorr, M.W.; Tanwar, V.; McDonald, M.P.; Wold, L.E.; et al. In utero exposure to fine particulate matter results in an altered neuroimmune phenotype in adult mice. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 279–288.

- Bernal-Melendez, E.; Lacroix, M.C.; Bouillaud, P.; Callebert, J.; Olivier, B.; Persuy, M.A.; Durieux, D.; Rousseau-Ralliard, D.; Aioun, J.; Cassee, F.; et al. Repeated gestational exposure to diesel engine exhaust affects the fetal olfactory system and alters olfactory-based behavior in rabbit offspring. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2019, 16, 5.

- Suzuki, T.; Oshio, S.; Iwata, M.; Saburi, H.; Odagiri, T.; Udagawa, T.; Sugawara, I.; Umezawa, M.; Takeda, K. In utero exposure to a low concentration of diesel exhaust affects spontaneous locomotor activity and monoaminergic system in male mice. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010, 7, 7.

- Umezawa, M.; Onoda, A.; Korshunova, I.; Jensen, A.C.O.; Koponen, I.K.; Jensen, K.A.; Khodosevich, K.; Vogel, U.; Hougaard, K.S. Maternal inhalation of carbon black nanoparticles induces neurodevelopmental changes in mouse offspring. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2018, 15, 36.

- Onoda, A.; Takeda, K.; Umezawa, M. Dysregulation of major functional genes in frontal cortex by maternal exposure to carbon black nanoparticle is not ameliorated by ascorbic acid pretreatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1126–1135.

- Onoda, A.; Takeda, K.; Umezawa, M. Pretreatment with N-acetyl cysteine suppresses chronic reactive astrogliosis following maternal nanoparticle exposure during gestational period. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 1012–1025.

- Feng, X.; Wu, J.; Lai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Liu, J.; Shao, L. Prenatal exposure to nanosized zinc oxide in rats: Neurotoxicity and postnatal impaired learning and memory ability. Nanomedicine 2017, 12, 777–795.

- Notter, T.; Aengenheister, L.; Weber-Stadlbauer, U.; Naegeli, H.; Wick, P.; Meyer, U.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T. Prenatal exposure to TiO2 nanoparticles in mice causes behavioral deficits with relevance to autism spectrum disorder and beyond. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 193.

- Hong, F.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, J.; Zhuang, J.; Sheng, L.; Wang, L. Nano-TiO2 inhibits development of the central nervous system and its mechanism in offspring mice. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2018, 66, 11767–11774.

- Mohammadipour, A.; Fazel, A.; Haghir, H.; Motejaded, F.; Rafatpanah, H.; Zabihi, H.; Hosseini, M.; Bideskan, A.E. Maternal exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles during pregnancy; impaired memory and decreased hippocampal cell proliferation in rat offspring. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 37, 617–625.

- Cui, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lei, Y.; Ma, M.; Cao, R.; Sun, T.; Xu, J.; Huo, M.; Cao, R.; et al. Prenatal exposure to nanoparticulate titanium dioxide enhances depressive-like behaviors in adult rats. Chemosphere 2014, 96, 99–104.

- Tabatabaei, S.R.; Moshrefi, M.; Askaripour, M. Prenatal exposure to silver nanoparticles causes depression like responses in mice. Ind. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 681–686.

- Klocke, C.; Allen, J.L.; Sobolewski, M.; Mayer-Proschel, M.; Blum, J.L.; Lauterstein, D.; Zelikoff, J.T.; Cory-Slechta, D.A. Neuropathological consequences of gestational exposure to concentrated ambient fine and ultrafine particles in the mouse. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 492–508.

- Ebrahimzadeh Bideskan, A.; Mohammadipour, A.; Fazel, A.; Haghir, H.; Rafatpanah, H.; Hosseini, M.; Rajabzadeh, A. Maternal exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles during pregnancy and lactation alters offspring hippocampal mRNA BAX and Bcl-2 levels, induces apoptosis and decreases neurogenesis. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 69, 329–337.

- Zhou, Y.; Hong, F.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hong, J.; Ze, Y.; Wang, L. Nanoparticulate titanium dioxide-inhibited dendritic development is involved in apoptosis and autophagy of hippocampal neurons in offspring mice. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 6, 889–901.

- Alimohammadi, S.; Hassanpour, S.; Moharramnejad, S. Effect of maternal exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles on reflexive motor behaviors in mice offspring. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2019, 25, 1049–1056.

- Alimohammadi, S.; Hosseini, M.S.; Behbood, L. Prenatal exposure to zinc oxide nanoparticles can induce depressive-like behaviors in mice offspring. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2019, 25, 401–409.