| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Irene Jiang | + 3945 word(s) | 3945 | 2021-05-31 10:27:38 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3945 | 2021-06-23 04:39:30 | | |

Video Upload Options

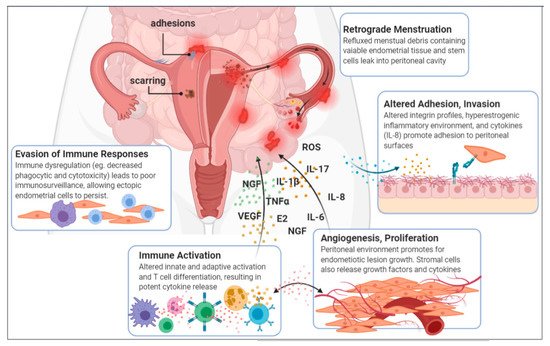

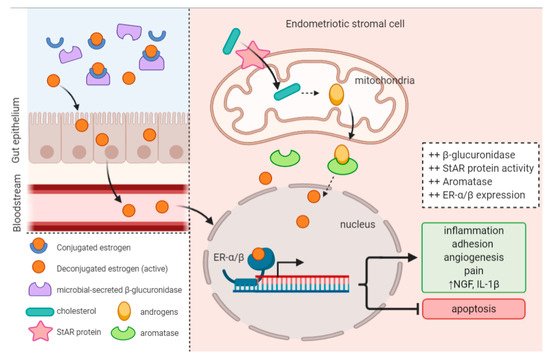

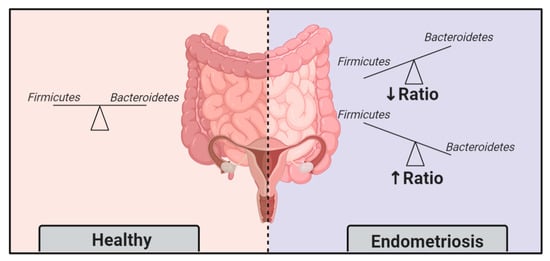

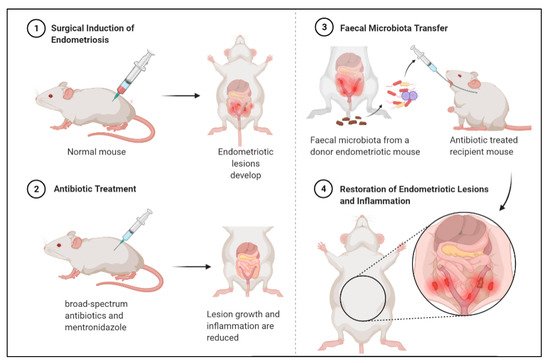

Imbalances in gut and reproductive tract microbiota composition, known as dysbiosis, disrupt normal immune function, leading to the elevation of proinflammatory cytokines, compromised immunosurveillance and altered immune cell profiles, all of which may contribute to the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Over time, this immune dysregulation can progress into a chronic state of inflammation, creating an environment conducive to increased adhesion and angiogenesis, which may drive the vicious cycle of endometriosis onset and progression. Recent studies have demonstrated both the ability of endometriosis to induce microbiota changes, and the ability of antibiotics to treat endometriosis. Endometriotic microbiotas have been consistently associated with diminished Lactobacillus dominance, as well as the elevated abundance of bacterial vaginosis-related bacteria and other opportunistic pathogens. Possible explanations for the implications of dysbiosis in endometriosis include the Bacterial Contamination Theory and immune activation, cytokine-impaired gut function, altered estrogen metabolism and signaling, and aberrant progenitor and stem-cell homeostasis.

1. Endometriosis

1.1. Introduction of Endometriosis

1.2. Aetiology and Pathogenesis

1.3. A Disease of the Immune System

| Macrophages | Neutrophils | NK Cells | T Cells | B Cells | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Immune Dysregulation |

|

|

|

|

|

| Implications on Endometriosis |

|

|

|

|

|

1.3.1. Elevated Inflammatory Mediators

1.3.2. Macrophages: Principal Contributors to the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis

1.3.3. Preconditioned Neutrophils

1.3.4. Impaired Natural Killer Cells

1.3.5. Altered T cell Differentiation

1.3.6. Activated B Cells

1.4. Estrogen Levels and Signaling Is Altered in Endometriosis

2. Evidence of an Intricate Connection

2.1. Endometriotic Women Exhibit Altered Microbiotas

2.2. Endometriosis Induces Gut Microbiota Alterations

2.3. Faecal Microbiota Transfer Induces Endometriosis

2.4. Diet-Induced Gut Microbiota Changes Reduce Endometriosis Risk

3. What Can This Mean for Endometriosis Care

3.1. Gynaecologic and Obstetric Applications of Microbiota Modulation

3.2. Treating Endometriosis with Antibiotics

3.3. Treating Endometriosis with Probiotics

3.4. A Mechanism for Known Treatments

3.5. Side Effects and Challenges

3.6. Opportunities for Diagnostics

References

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Koga, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Viganò, P. Endometriosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 9.

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256.

- Busacca, M.; Vignali, M. Ovarian endometriosis: From pathogenesis to surgical treatment. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 15, 321–326.

- Dunselman, G.A.J.; Vermeulen, N.; Becker, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; D’Hooghe, T.; De Bie, B.; Heikinheimo, O.; Horne, A.W.; Kiesel, L.; Nap, A.; et al. ESHRE Guideline: Management of Women with Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 400–412.

- Eskenazi, B.; Warner, M.L. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 24, 235–258.

- Vercellini, P.; Fedele, L.; Aimi, G.; Pietropaolo, G.; Consonni, D.; Crosignani, P.G. Association between Endometriosis Stage, Lesion Type, Patient Characteristics and Severity of Pelvic Pain Symptoms: A Multivariate Analysis of over 1000 Patients. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 266–271.

- Arion, K.; Orr, N.L.; Noga, H.; Allaire, C.; Williams, C.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Yong, P.J. A Quantitative Analysis of Sleep Quality in Women with Endometriosis. J. Women’s Health 2020, 29, 1209–1215.

- Shum, L.K.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Allaire, C.; Williams, C.; Noga, H.; Albert, A.; Lisonkova, S.; Yong, P.J. Deep Dyspareunia and Sexual Quality of Life in Women with Endometriosis. Sex. Med. 2018, 6, 224–233.

- Sepulcri, R.d.P.; do Amaral, V.F. Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Quality of Life in Women with Pelvic Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2009, 142, 53–56.

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The Burden of Endometriosis: Costs and Quality of Life of Women with Endometriosis and Treated in Referral Centres. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2073.

- Vercellini, P.; Vigano, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–276.

- Bedaiwy, M.A.; Barker, N.M. Evidence Based Surgical Management of Endometriosis. Middle East. Fertil. Soc. J. 2012, 17, 57–60.

- Bedaiwy, M.A.; Alfaraj, S.; Yong, P.; Casper, R. New Developments in the Medical Treatment of Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 555–565.

- Vercellini, P.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P.; Abbiati, A.; Daguati, R.; Crosignani, P.G. Endometriosis: Current and Future Medical Therapies. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 22, 275–306.

- Yovich, J.L.; Rowlands, P.K.; Lingham, S.; Sillender, M.; Srinivasan, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: Look No Further than John Sampson. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 7–11.

- Halme, J.; Hammond, M.G.; Hulka, J.F.; Raj, S.G.; Talbert, L.M. Retrograde Menstruation in Healthy Women and in Patients with Endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1984, 64, 151–154.

- Laschke, M.W.; Menger, M.D. The Gut Microbiota: A Puppet Master in the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 68.e1–68.e4.

- Harada, T.; Iwabe, T.; Terakawa, N. Role of Cytokines in Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 76, 1–10.

- Klemmt, P.A.B.; Carver, J.G.; Koninckx, P.; McVeigh, E.J.; Mardon, H.J. Endometrial Cells from Women with Endometriosis Have Increased Adhesion and Proliferative Capacity in Response to Extracellular Matrix Components: Towards a Mechanistic Model for Endometriosis Progression. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 3139–3147.

- Garcia-Velasco, J.A.; Arici, A. P-255. Interleukin-8 Stimulates Endometrial Stromal Cell Adhesion to Fibronectin. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 268.

- Symons, L.K.; Miller, J.E.; Kay, V.R.; Marks, R.M.; Liblik, K.; Koti, M.; Tayade, C. The Immunopathophysiology of Endometriosis. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 748–762.

- Cosín, R.; Gilabert-Estellés, J.; Ramón, L.A.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; Gilabert, J.; Chirivella, M.; Braza-Boïls, A.; España, F.; Estellés, A. Influence of Peritoneal Fluid on the Expression of Angiogenic and Proteolytic Factors in Cultures of Endometrial Cells from Women with Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 398–405.

- McLaren, J.; Prentice, A.; Charnock-Jones, D.S.; Millican, S.A.; Müller, K.H.; Sharkey, A.M.; Smith, S.K. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Is Produced by Peritoneal Fluid Macrophages in Endometriosis and Is Regulated by Ovarian Steroids. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 482–489.

- Iwabe, T.; Harada, T.; Tsudo, T.; Nagano, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Tanikawa, M.; Terakawa, N. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Promotes Proliferation of Endometriotic Stromal Cells by Inducing Interleukin-8 Gene and Protein Expression. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 824–829.

- Leibovich, S.J.; Polverini, P.J.; Shepard, H.M.; Wiseman, D.M.; Shively, V.; Nuseir, N. Macrophage-Induced Angiogenesis Is Mediated by Tumour Necrosis Factor- α. Nature 1987, 329, 630–632.

- Nothnick, W.B. Treating Endometriosis as an Autoimmune Disease. Fertil. Steril. 2001, 76, 223–231.

- García-Peñarrubia, P.; Ruiz-Alcaraz, A.J.; Martínez-Esparza, M.; Marín, P.; Machado-Linde, F. Hypothetical Roadmap towards Endometriosis: Prenatal Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Pollutant Exposure, Anogenital Distance, Gut-Genital Microbiota and Subclinical Infections. Hum. Reprod. Update 2020, 26, 214–246.

- Shigesi, N.; Kvaskoff, M.; Kirtley, S.; Feng, Q.; Fang, H.; Knight, J.C.; Missmer, S.A.; Rahmioglu, N.; Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M. The Association between Endometriosis and Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2019, 25, 486–503.

- Tsudo, T.; Harada, T.; Iwabe, T.; Tanikawa, M.; Nagano, Y.; Ito, M.; Taniguchi, F.; Terakawa, N. Altered Gene Expression and Secretion of Interleukin-6 in Stromal Cells Derived from Endometriotic Tissues. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 73, 205–211.

- Tseng, J.F.; Ryan, I.P.; Milam, T.D.; Murai, J.T.; Schriock, E.D.; Landers, D.V.; Taylor, R.N. Interleukin-6 Secretion in Vitro Is up-Regulated in Ectopic and Eutopic Endometrial Stromal Cells from Women with Endometriosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 1118–1122.

- Beste, M.T.; Pfäffle-Doyle, N.; Prentice, E.A.; Morris, S.N.; Lauffenburger, D.A.; Isaacson, K.B.; Griffith, L.G. Molecular Network Analysis of Endometriosis Reveals a Role for C-Jun–Regulated Macrophage Activation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 222ra16.

- Mu, F.; Harris, H.R.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Missmer, S.A. A Prospective Study of Inflammatory Markers and Risk of Endometriosis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 515–522.

- Vallvé-Juanico, J.; Santamaria, X.; Vo, K.C.; Houshdaran, S.; Giudice, L.C. Macrophages Display Proinflammatory Phenotypes in the Eutopic Endometrium of Women with Endometriosis with Relevance to an Infectious Etiology of the Disease. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 1118–1128.

- Lin, Y.-J.; Lai, M.-D.; Lei, H.-Y.; Wing, L.-Y.C. Neutrophils and Macrophages Promote Angiogenesis in the Early Stage of Endometriosis in a Mouse Model. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 1278–1286.

- Bacci, M.; Capobianco, A.; Monno, A.; Cottone, L.; Di Puppo, F.; Camisa, B.; Mariani, M.; Brignole, C.; Ponzoni, M.; Ferrari, S.; et al. Macrophages Are Alternatively Activated in Patients with Endometriosis and Required for Growth and Vascularization of Lesions in a Mouse Model of Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2009, 175, 547–556.

- Hirayama, D.; Iida, T.; Nakase, H. The Phagocytic Function of Macrophage-Enforcing Innate Immunity and Tissue Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 19, 92.

- Salamonsen, L.A.; Zhang, J.; Brasted, M. Leukocyte Networks and Human Endometrial Remodelling. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 57, 95–108.

- Berbic, M.; Schulke, L.; Markham, R.; Tokushige, N.; Russell, P.; Fraser, I.S. Macrophage Expression in Endometrium of Women with and without Endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 325–332.

- Bedaiwy, M.A. Endometrial Macrophages, Endometriosis, and Microbiota: Time to Unravel the Complexity of the Relationship. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 112, 1049–1050.

- Lousse, J.-C.; Van Langendonckt, A.; González-Ramos, R.; Defrère, S.; Renkin, E.; Donnez, J. Increased Activation of Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-ΚB) in Isolated Peritoneal Macrophages of Patients with Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 217–220.

- Milewski, Ł.; Dziunycz, P.; Barcz, E.; Radomski, D.; Roszkowski, P.I.; Korczak-Kowalska, G.; Kamiński, P.; Malejczyk, J. Increased Levels of Human Neutrophil Peptides 1, 2, and 3 in Peritoneal Fluid of Patients with Endometriosis: Association with Neutrophils, T Cells and IL-8. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 91, 64–70.

- Karmarkar, D.; Rock, K.L. Microbiota Signalling through MyD88 Is Necessary for a Systemic Neutrophilic Inflammatory Response. Immunology 2013, 140, 483–492.

- Wu, M.-Y.; Yang, J.-H.; Chao, K.-H.; Hwang, J.-L.; Yang, Y.-S.; Ho, H.-N. Increase in the Expression of Killer Cell Inhibitory Receptors on Peritoneal Natural Killer Cells in Women with Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2000, 74, 1187–1191.

- Podgaec, S.; Abrao, M.S.; Dias, J.A., Jr.; Rizzo, L.V.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Baracat, E.C. Endometriosis: An Inflammatory Disease with a Th2 Immune Response Component. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 1373–1379.

- Antsiferova, Y.S.; Sotnikova, N.Y.; Posiseeva, L.V.; Shor, A.L. Changes in the T-Helper Cytokine Profile and in Lymphocyte Activation at the Systemic and Local Levels in Women with Endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2005, 84, 1705–1711.

- Gogacz, M.; Winkler, I.; Bojarska-Junak, A.; Tabarkiewicz, J.; Semczuk, A.; Rechberger, T.; Adamiak, A. Increased Percentage of Th17 Cells in Peritoneal Fluid Is Associated with Severity of Endometriosis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 117, 39–44.

- Laux-Biehlmann, A.; d’Hooghe, T.; Zollner, T.M. Menstruation Pulls the Trigger for Inflammation and Pain in Endometriosis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 36, 270–276.

- Ahn, S.H.; Edwards, A.K.; Singh, S.S.; Young, S.L.; Lessey, B.A.; Tayade, C. IL-17A Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis by Triggering Proinflammatory Cytokines and Angiogenic Growth Factors. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 2591–2600.

- Shen, P.; Fillatreau, S. Antibody-Independent Functions of B Cells: A Focus on Cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 441–452.

- Randall, G.W.; Gantt, P.A.; Poe-Zeigler, R.L.; Bergmann, C.A.; Noel, M.E.; Strawbridge, W.R.; Richardson-Cox, B.; Hereford, J.R.; Reiff, R.H. Serum Antiendometrial Antibodies and Diagnosis of Endometriosis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 58, 374–382.

- Chantalat, E.; Valera, M.-C.; Vaysse, C.; Noirrit, E.; Rusidze, M.; Weyl, A.; Vergriete, K.; Buscail, E.; Lluel, P.; Fontaine, C.; et al. Estrogen Receptors and Endometriosis. Available online: (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- Galvankar, M.; Singh, N.; Modi, D. Estrogen Is Essential but Not Sufficient to Induce Endometriosis. J. Biosci. 2017, 42, 251–263.

- Reis, F.M.; Petraglia, F.; Taylor, R.N. Endometriosis: Hormone Regulation and Clinical Consequences of Chemotaxis and Apoptosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2013, 19, 406–418.

- Han, S.J.; Jung, S.Y.; Wu, S.-P.; Hawkins, S.M.; Park, M.J.; Kyo, S.; Qin, J.; Lydon, J.P.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tsai, M.-J.; et al. Estrogen Receptor β Modulates Apoptosis Complexes and the Inflammasome to Drive the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Cell 2015, 163, 960–974.

- Burns, K.A.; Rodriguez, K.F.; Hewitt, S.C.; Janardhan, K.S.; Young, S.L.; Korach, K.S. Role of Estrogen Receptor Signaling Required for Endometriosis-Like Lesion Establishment in a Mouse Model. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3960–3971.

- Morotti, M.; Vincent, K.; Becker, C.M. Mechanisms of Pain in Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 209, 8–13.

- Bulun, S.E. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 268–279.

- Ervin, S.M.; Li, H.; Lim, L.; Roberts, L.R.; Liang, X.; Mani, S.; Redinbo, M.R. Gut Microbial β-Glucuronidases Reactivate Estrogens as Components of the Estrobolome That Reactivate Estrogens. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18586–18599.

- Baker, J.M.; Al-Nakkash, L.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M.M. Estrogen–Gut Microbiome Axis: Physiological and Clinical Implications. Maturitas 2017, 103, 45–53.

- Goedert, J.J.; Jones, G.; Hua, X.; Xu, X.; Yu, G.; Flores, R.; Falk, R.T.; Gail, M.H.; Shi, J.; Ravel, J.; et al. Investigation of the Association between the Fecal Microbiota and Breast Cancer in Postmenopausal Women: A Population-Based Case-Control Pilot Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107.

- Mikhael, S.; Punjala-Patel, A.; Gavrilova-Jordan, L. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Disorders Impacting Female Fertility. Available online: (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Huang, C. Interaction between Microbes and Host Intestinal Health: Modulation by Dietary Nutrients and Gut-Brain-Endocrine-Immune Axis. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015, 16, 592.

- Baj, A.; Moro, E.; Bistoletti, M.; Orlandi, V.; Crema, F.; Giaroni, C. Glutamatergic Signaling Along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Available online: (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Jones, L.A.; Sun, E.W.; Martin, A.M.; Keating, D.J. The Ever-Changing Roles of Serotonin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 125, 105776.

- Hiller-Sturmhöfel, S.; Bartke, A. The Endocrine System. Alcohol Health Res. World 1998, 22, 153–164.

- Tai, F.-W.; Chang, C.Y.-Y.; Chiang, J.-H.; Lin, W.-C.; Wan, L. Association of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease with Risk of Endometriosis: A Nationwide Cohort Study Involving 141,460 Individuals. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 379.

- Ata, B.; Yildiz, S.; Turkgeldi, E.; Brocal, V.P.; Dinleyici, E.C.; Moya, A.; Urman, B. The Endobiota Study: Comparison of Vaginal, Cervical and Gut Microbiota Between Women with Stage 3/4 Endometriosis and Healthy Controls. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2204.

- Walther-António, M.R.S.; Chen, J.; Multinu, F.; Hokenstad, A.; Distad, T.J.; Cheek, E.H.; Keeney, G.L.; Creedon, D.J.; Nelson, H.; Mariani, A.; et al. Potential Contribution of the Uterine Microbiome in the Development of Endometrial Cancer. Available online: (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- Khan, K.N.; Fujishita, A.; Masumoto, H.; Muto, H.; Kitajima, M.; Masuzaki, H.; Kitawaki, J. Molecular Detection of Intrauterine Microbial Colonization in Women with Endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 199, 69–75.

- Hernandes, C.; Silveira, P.; Sereia, A.F.R.; Christoff, A.P.; Mendes, H.; de Oliveira, L.F.V.; Podgaec, S. Microbiome Profile of Deep Endometriosis Patients: Comparison of Vaginal Fluid, Endometrium and Lesion. Available online: (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Tang, H.; Zeng, L.; Wu, R. Microbiota Composition and Distribution along the Female Reproductive Tract of Women with Endometriosis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 15.

- Dols, J.A.M.; Molenaar, D.; van der Helm, J.J.; Caspers, M.P.M.; de Kat Angelino-Bart, A.; Schuren, F.H.J.; Speksnijder, A.G.C.L.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Richardus, J.H.; Boon, M.E.; et al. Molecular Assessment of Bacterial Vaginosis by Lactobacillus Abundance and Species Diversity. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 180.

- Dols, J.A.M.; Smit, P.W.; Kort, R.; Reid, G.; Schuren, F.H.J.; Tempelman, H.; Bontekoe, T.R.; Korporaal, H.; Boon, M.E. Microarray-Based Identification of Clinically Relevant Vaginal Bacteria in Relation to Bacterial Vaginosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 204, 305.e1–305.e7.

- Yuan, M.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; An, M.; Wang, G. Endometriosis Induces Gut Microbiota Alterations in Mice. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 607–616.

- Bailey, M.T.; Coe, C.L. Endometriosis Is Associated with an Altered Profile of Intestinal Microflora in Female Rhesus Monkeys. Hum. Reprod. 2002, 17, 1704–1708.

- Chadchan, S.B.; Cheng, M.; Parnell, L.A.; Yin, Y.; Schriefer, A.; Mysorekar, I.U.; Kommagani, R. Antibiotic Therapy with Metronidazole Reduces Endometriosis Disease Progression in Mice: A Potential Role for Gut Microbiota. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1106–1116.

- Missmer, S.A.; Chavarro, J.E.; Malspeis, S.; Bertone-Johnson, E.R.; Hornstein, M.D.; Spiegelman, D.; Barbieri, R.L.; Willett, W.C.; Hankinson, S.E. A Prospective Study of Dietary Fat Consumption and Endometriosis Risk. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1528–1535.

- Hopeman, M.M.; Riley, J.K.; Frolova, A.I.; Jiang, H.; Jungheim, E.S. Serum Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2015, 22, 1083–1087.

- Tomio, K.; Kawana, K.; Taguchi, A.; Isobe, Y.; Iwamoto, R.; Yamashita, A.; Kojima, S.; Mori, M.; Nagamatsu, T.; Arimoto, T.; et al. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Suppress the Cystic Lesion Formation of Peritoneal Endometriosis in Transgenic Mouse Models. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73085.

- Attaman, J.A.; Stanic, A.K.; Kim, M.; Lynch, M.P.; Rueda, B.R.; Styer, A.K. The Anti-Inflammatory Impact of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids During the Establishment of Endometriosis-Like Lesions. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 72, 392–402.

- Ilich, J.Z.; Kelly, O.J.; Kim, Y.; Spicer, M.T. Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation Perpetuated by Modern Diet as a Promoter of Obesity and Osteoporosis. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 139–148.

- Kelly, O.J.; Gilman, J.C.; Kim, Y.; Ilich, J.Z. Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids May Mutually Benefit Both Obesity and Osteoporosis. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 521–533.

- Molina, N.M.; Sola-Leyva, A.; Saez-Lara, M.J.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Tubić-Pavlović, A.; Romero, B.; Clavero, A.; Mozas-Moreno, J.; Fontes, J.; Altmäe, S. New Opportunities for Endometrial Health by Modifying Uterine Microbial Composition: Present or Future? Available online: (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Kyono, K.; Hashimoto, T.; Kikuchi, S.; Nagai, Y.; Sakuraba, Y. A Pilot Study and Case Reports on Endometrial Microbiota and Pregnancy Outcome: An Analysis Using 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing among IVF Patients, and Trial Therapeutic Intervention for Dysbiotic Endometrium. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2019, 18, 72–82.

- Cicinelli, E.; Matteo, M.; Tinelli, R.; Pinto, V.; Marinaccio, M.; Indraccolo, U.; De Ziegler, D.; Resta, L. Chronic Endometritis due to Common Bacteria Is Prevalent in Women with Recurrent Miscarriage as Confirmed by Improved Pregnancy Outcome after Antibiotic Treatment. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 640–647.

- Cicinelli, E.; Matteo, M.; Trojano, G.; Mitola, P.C.; Tinelli, R.; Vitagliano, A.; Crupano, F.M.; Lepera, A.; Miragliotta, G.; Resta, L. Chronic Endometritis in Patients with Unexplained Infertility: Prevalence and Effects of Antibiotic Treatment on Spontaneous Conception. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 79, e12782.

- McQueen, D.B.; Bernardi, L.A.; Stephenson, M.D. Chronic Endometritis in Women with Recurrent Early Pregnancy Loss and/or Fetal Demise. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1026–1030.

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, W.; Wu, D.; Lei, L.; Chen, G. Confirmation of Chronic Endometritis in Repeated Implantation Failure and Success Outcome in IVF-ET after Intrauterine Delivery of the Combined Administration of Antibiotic and Dexamethasone. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019, 82, e13177.

- Khodaverdi, S.; Mohammadbeigi, R.; Khaledi, M.; Mesdaghinia, L.; Sharifzadeh, F.; Nasiripour, S.; Gorginzadeh, M. Beneficial Effects of Oral Lactobacillus on Pain Severity in Women Suffering from Endometriosis: A Pilot Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2019, 13, 178–183.

- Itoh, H.; Uchida, M.; Sashihara, T.; Ji, Z.-S.; Li, J.; Tang, Q.; Ni, S.; Song, L.; Kaminogawa, S. Lactobacillus Gasseri OLL2809 Is Effective Especially on the Menstrual Pain and Dysmenorrhea in Endometriosis Patients: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Cytotechnology 2011, 63, 153–161.

- Uchida, M.; Kobayashi, O. Effects of Lactobacillus Gasseri OLL2809 on the Induced Endometriosis in Rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 1879–1881.

- Itoh, H.; Sashihara, T.; Hosono, A.; Kaminogawa, S.; Uchida, M. Lactobacillus Gasseri OLL2809 Inhibits Development of Ectopic Endometrial Cell in Peritoneal Cavity via Activation of NK Cells in a Murine Endometriosis Model. Cytotechnology 2011, 63, 205–210.

- Cao, Y.; Jiang, C.; Jia, Y.; Xu, D.; Yu, Y. Letrozole and the Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shaofu Zhuyu Decoction, Reduce Endometriotic Disease Progression in Rats: A Potential Role for Gut Microbiota. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 3687498.

- Meng, J.; Meng, J.; Banerjee, S.; Banerjee, S.; Zhang, L.; Sindberg, G.; Moidunny, S.; Li, B.; Robbins, D.J.; Girotra, M.; et al. Opioids Impair Intestinal Epithelial Repair in HIV-Infected Humanized Mice. Available online: (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229–241.

- Gottschick, C.; Deng, Z.L.; Vital, M.; Masur, C.; Abels, C.; Pieper, D.H.; Wagner-Döbler, I. The urinary microbiota of men and women and its changes in women during bacterial vaginosis and antibiotic treatment. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 99.

- Zhang, S.; Chen, D.C. Facing a new challenge: The adverse effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota and host immunity. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1135–1138.

- Perrotta, A.R.; Borrelli, G.M.; Martins, C.O.; Kallas, E.G.; Sanabani, S.S.; Griffith, L.G.; Alm, E.J.; Abrao, M.S. The Vaginal Microbiome as a Tool to Predict RASRM Stage of Disease in Endometriosis: A Pilot Study. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 1064–1073.