| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marco Cerbón | + 4732 word(s) | 4732 | 2021-06-01 08:57:02 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 4732 | 2021-06-15 03:34:05 | | | | |

| 3 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 4732 | 2021-06-17 09:39:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

Dietary fatty acids (DFAs) play key roles in different metabolic processes in humans and other mammals. DFAs have been considered beneficial for health, particularly polyunsaturated (PUFAs) and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs).However both polyunsatyrated and saturated DFAs are both present in normal diet. On the other hand , microRNAs (miRNAs) exert their function on DFA metabolism by modulating gene expression and have drawn great attention for their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. DFAs have been shown to induce and repress miRNA expression associated with metabolic disease and inflammation in different cell types and organisms, both in vivo and in vitro, depending on varying combinations of DFAs, doses, and the duration of treatment.

1. Introduction

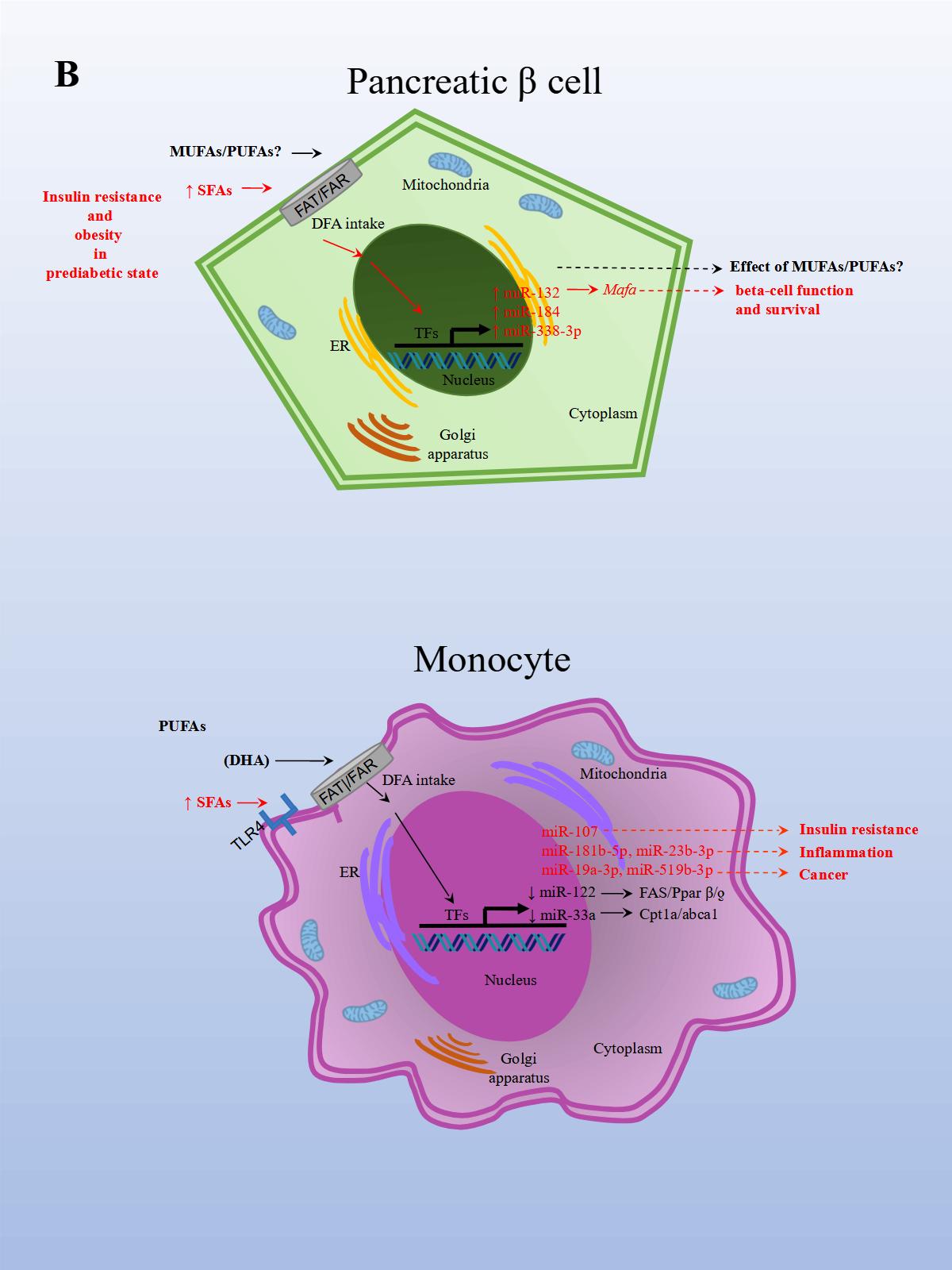

2. DFAs Alter miRNA Expression Associated with Metabolic Disorders

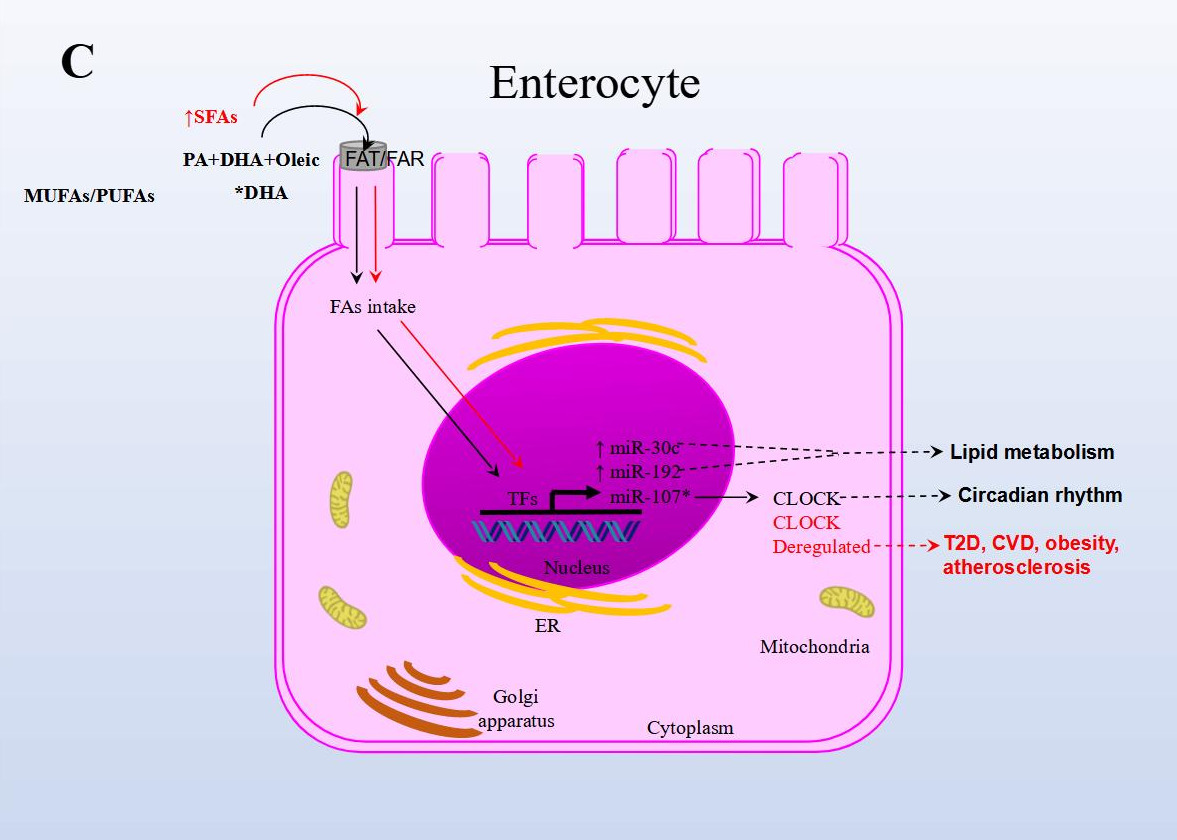

The effects of PUFAs on miRNA expression were assessed in a healthy population. The effect of DFAs in a PUFA-enriched diet, inferred from plasma fatty acid concentration, was linked to changes in circulating miRNAs. In the first experiment, 20 miRNAs were identified and differentially expressed in healthy women after consuming PUFAs in their diet. In a subsequent study, ten miRNAs were validated in both men and women in a larger group. Changes were seen in miRNA expression after eight weeks with daily walnut and almond intake [37]. In particular, miR-221 and CRP (high-sensitivity C-reactive protein) expressions were repressed after treatment with PUFAs. In another study performed in a healthy population, the effects of a single dose of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) were detected after four hours of intake. EVOO is a complex nutrient mix composed primarily of MUFAs (65.2%–80.8%). Other components include PUFAs (7.0–15.5%), tocopherols, squalene, pigments, and other compounds, such as phenolic compounds, triterpene dialcohols, and B-sitosterol (Jimenez-Lopez et al., 2020). Fourteen miRNAs were differentially modified, and seven were validated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The validated miRNAs have potentially beneficial effects on insulin resistance (i.e., miR-107), inflammation (i.e., miR-181b-5p, miR-23b-3p), and cancer (miR-19a-3p, miR-519b-3p), and may play an important role in preventing the onset of CVD and cancer [38].

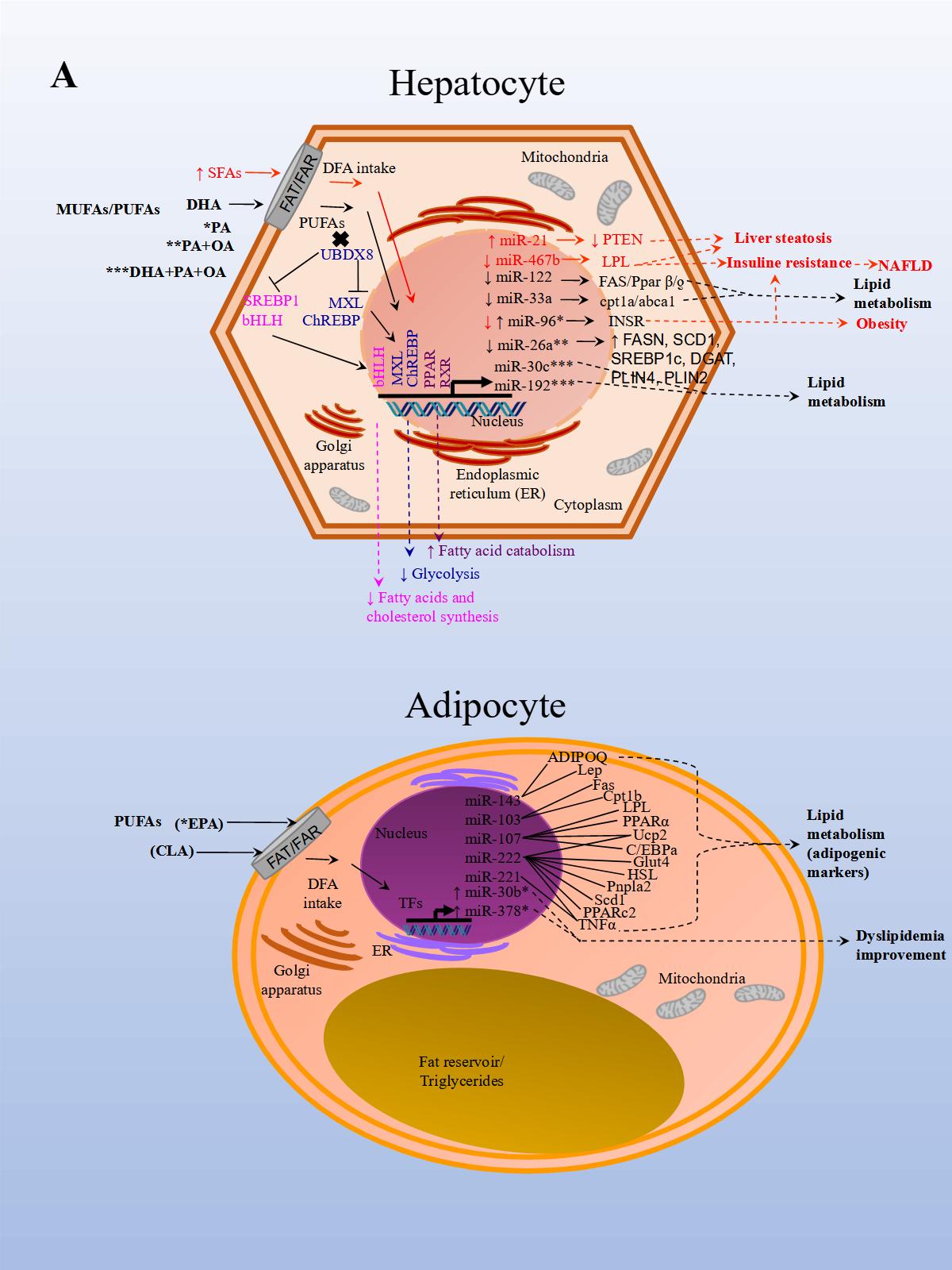

A recent study aimed to analyze the effect of EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) in brown adipose tissue (BAT) thermogenesis, which represents a target to promote weight loss in obesity. The effect of EPA treatment in mice after twelve weeks was analyzed in murine inguinal white and brown adipose tissue to demonstrate how brown fat and muscle cooperate to maintain normal body temperature. It has been shown that BAT can be stimulated to increase energy expenditure, and hence offers new therapeutic opportunities in obesity [39]. The study reported that treatment with EPA increased oxygen consumption, but, importantly, modulated free fatty acid receptor 4 (Ffar 4), a functional receptor for ω-3 PUFAs, which enhanced brown adipogenesis through the upregulation of miR-30b and miR-378, and activation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) [40] (Figure 1 A, Adipocyte). In another study, both a HFD administered to mice for 14 weeks and palmitate treatment in HepG2 cells, induced miR-96 expression in the liver of the mice and the cells. miR-96 directly targeted insulin receptor (INSR) and Insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and repressed gene expression post-transcriptionally. Additionally, the liver of HFD fed mice and the treated hepatocytes exhibited impairment of insulin-signaling and glycogen synthesis, revealing miR-96 as a promoter of hepatic insulin resistance pathogenesis in obese states [41] (Figure 1 A, Hepatocyte).

Although the consumption of high quantities of TFAs associated with CVD risk and a decrease in HDL has been well established, the effect of ruminant TFAs (rTFA, naturally occurring in ruminant meat, and milk fat) on metabolic markers was reported until only recently. The next study analyzed the HDL-carried miRNA expression of two of the most abundant HDL-carried miRNAs found in plasma. After nine men were given a diet high in either industrial TFAs (iTFAs, produced industrially by partial hydrogenation of vegetable oils), or rTFAs, designed in a previous study that measured the effect of rTFAs on metabolic markers [42], miRNA expression was measured in blood plasma. miR-223-3p concentrations correlated negatively with HDL levels after a diet high in iTFAs, and positively with C-reactive protein levels after a diet high in rTFAs. Conversely, miR-135-3p concentrations correlated positively with both total triglyceride levels after a diet high in iTFAs, and with LDL levels after a diet high in rTFAs. The results suggest that diets high in TFAs, whether of industrial or ruminant origin, alter HDL-carried miRNA concentrations, and are associated with changes in CVD risk factors [10]. One year later in a similar study model, the same group analyzed whether diets with different concentrations of iTFAs or rTFAs modify contributions of HDL-carried miRNAs associated with CVD, to the plasmatic pool. HDL-carried miR-103a-3p, miR-221-3p, miR-222-3p, miR-376c-3p, miR-199a-5p, miR-30a-5p, miR-328-3p, miR-423-3p, miR-124-3p, miR-150-5p, miR-31-5p, miR-375, and miR-133a-3p varied in contribution to the plasmatic pool after diets high in iTFAS and rTFAs were given. The results show that diets high in TFAs modify the HDL-carried miRNA profile, contribute differently to the plasmatic pool, and suggest that these miRNAs may be involved in the regulation of cardioprotective HDL functions [43].

In another NAFLD model, the effect of fish oil on miRNA expression in rat liver tissue was analyzed. Animals were either fed a diet rich in lard alone or supplemented with fish oil. The results from sequencing identified 79 miRNAs as differentially expressed in the group supplemented with fish oil compared to the control group. Importantly, the repressed expression of rno-miR-29c target-regulated the expression of Period Circadian Regulator 3 (Per3), a critical circadian rhythm gene associated with obesity and diabetes. rno-miR-328 expression was induced, and target-regulated Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin Type 9 (Pcsk9), a gene that plays a crucial role in LDL receptor degradation and cholesterol metabolism. Finally, miR-30d expression was induced and in turn regulated the expression of its target Suppressor Of Cytokine Signaling 1 (Socs1), a gene involved in immunity and insulin and leptin signaling, respectively [44].

Finally, in an in vitro NAFLD model, HepG2 cells treated with free fatty acids (palmitic and oleic acids, 1:2) resulted in miR-26a repressed endogenous expression. Additionally, miR-26a over-expressed in cells, induced a protective role on lipid metabolism and the progression of NAFLD [28] (Figure 1 A, Hepatocyte).

The results of these studies also demonstrated that miRNA expression is modified by DFA intervention which in turn regulates genes involved with obesity, NAFLD, CVD, and other metabolic diseases. Interventions with unsaturated FAs seem to have a beneficial effect on metabolism while the opposite seems to occur with SFAs and TFAs.

3. DFAs Alter miRNA Expression Associated with Inflammation

The consumption of DFAs had traditionally been associated with inflammation, with the inflammatory response depending on the amount and type of DFAs consumed. However, controversy exists, as recent studies have also demonstrated that high fat and ketogenic diets with SFAs, do not increase serum saturated fat content in humans, and are not associated with increased inflammation [45]. In previous studies, it was reported that meals high in fat content promote translocation of endotoxins, mainly lipopolysaccharide (LPS) produced by the gut microbiome, into the bloodstream. LPS stimulates the inflammatory response which may be both acute and chronic. SFAs may also induce inflammation by mimicking the actions of LPS [46]. Firstly, SFAs are an essential structural component of bacterial endotoxins [47]. Additionally, DFAs can promote endotoxin absorption [48]. Lastly, pro-inflammatory compounds in food may be absorbed and prompt the inflammatory response directly by stimulating Toll-like receptors [49] found on cells of the innate immune system that lead to NF-kB activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression [50][51]. It has also been reported that as postprandial lipemia is strongly correlated to endotoxin absorption, the addition of PUFAs and MFAs in the diet reduces LPS pro-inflammatory activity [46][52]. Diets high in SFAs have been shown to promote metabolic endotoxemia not only through changes in the microbiome and bacterial end-products, but also alter intestinal physiology and barrier function, and enterohepatic circulation of bile.

In an inflammation rat model, animals were fed rat chow with added lard and corn oil, low in ω-3 PUFAs, to induce inflammation and mimic the common human diet. After the animals were divided into three groups, each group was either treated with ω-3 PUFAs, ω-6 PUFAs, or saline solution for 16 weeks. In the ω-3 treated rats, CD8+ T (cluster of differentiation 8 T cells) and Treg populations significantly increased, and IL-6 (Interleukin 6), CRP (c-reactive protein), and TNF-α expression levels decreased. This suggests that the ω-3 treated group was better able to reduce inflammation related to a diet low in ω-3. The opposite resulted in the ω-6 treated group. Moreover, obesity and a reduction in omental fat in the ω-3 treated group were significantly lower compared to controls. Later, miRNA expression was analyzed in serum, PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells), white adipose tissue, and hepatocytes. Importantly, in the ω-3 treated group, miR-146b-5p (directly targets TNF and is involved in TLR (Toll-like receptor) and TCR (T cell receptor) pathways) expression was significantly upregulated in serum compared to controls. While miR-19b-3p (directly targets PTEN and is involved in cell cycle and MAPK pathways) and miR-183-5p (directly targets PTEN and TNF and involved in MAPK pathways) expression levels in the ω-3 treated group was significantly upregulated in serum and PBMCs compared to controls. In the ω-3 treated group, miR-29c and miR-292-3p expression levels were upregulated in serum compared to controls, although not significantly. The results demonstrated that the expression levels for these miRNAs were regulated by PUFAs in the diet [53]. Altogether, these findings suggest that certain DFAs in the diet are capable of modulating miRNA expression related to increased inflammation and obesity, whereas PUFAs in the diet, particularly EPA and DHA, seem to do the opposite.

4. Conclusions

References

- E. Scorletti; C.D. Byrne; Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Hepatic Lipid Metabolism, and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Annual Review of Nutrition 2013, 33, 231-248, 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071812-161230.

- Laura García-Segura; Martha Elva Perezandrade; Juan Miranda-Ríos; The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in the Regulation of Gene Expression by Nutrients. Journal of Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics 2012, 6, 16-31, 10.1159/000345826.

- Norman J. Temple; Fat, Sugar, Whole Grains and Heart Disease: 50 Years of Confusion. Nutrients 2018, 10, 39, 10.3390/nu10010039.

- Victoria M. Gershuni; Saturated Fat: Part of a Healthy Diet. Current Nutrition Reports 2018, 7, 85-96, 10.1007/s13668-018-0238-x.

- James J. DiNicolantonio; Sean C. Lucan; James H. O’Keefe; The Evidence for Saturated Fat and for Sugar Related to Coronary Heart Disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 2016, 58, 464-472, 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.11.006.

- Arne Astrup; Faidon Magkos; Dennis M. Bier; J. Thomas Brenna; Marcia C. De Oliveira Otto; James O. Hill; Janet C. King; Andrew Mente; Jose M. Ordovas; Jeff S. Volek; et al.Salim YusufRonald M. Krauss Saturated Fats and Health: A Reassessment and Proposal for Food-Based Recommendations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020, 76, 844-857, 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.077.

- Peter L. Zock; Wendy A. M. Blom; Joyce A. Nettleton; Gerard Hornstra; Progressing Insights into the Role of Dietary Fats in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Current Cardiology Reports 2016, 18, 1-13, 10.1007/s11886-016-0793-y.

- Gretchen Vannice; Heather Rasmussen; Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Dietary Fatty Acids for Healthy Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2013, 114, 136-153, 10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.001.

- Michelle A. Briggs; Kristina S. Petersen; Penny M. Kris-Etherton; Saturated Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease: Replacements for Saturated Fat to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk. Healthcare 2017, 5, 29, 10.3390/healthcare5020029.

- Véronique Desgagné; Simon-Pierre Guay; Renée Guérin; François Corbin; Patrick Couture; Benoit Lamarche; Luigi Bouchard; Variations in HDL-carried miR-223 and miR-135a concentrations after consumption of dietary trans fat are associated with changes in blood lipid and inflammatory markers in healthy men - an exploratory study. Epigenetics 2016, 11, 438-448, 10.1080/15592294.2016.1176816.

- Eva Tvrzicka; Lefkothea-Stella Kremmyda; Barbora Stankova; Ales Zak; FATTY ACIDS AS BIOCOMPOUNDS: THEIR ROLE IN HUMAN METABOLISM, HEALTH AND DISEASE - A REVIEW. PART 1: CLASSIFICATION, DIETARY SOURCES AND BIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS. Biomedical Papers 2011, 155, 117-130, 10.5507/bp.2011.038.

- Philip C. Calder; Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2015, 39, 18S-32S, 10.1177/0148607115595980.

- Julián F. Hernando Boigues; Núria Mach; Efecto de los ácidos grasos poliinsaturados en la prevención de la obesidad a través de modificaciones epigenéticas. Endocrinología y Nutrición 2015, 62, 338-349, 10.1016/j.endonu.2015.03.009.

- Toshinari Takamura; Masao Honda; Yoshio Sakai; Hitoshi Ando; Akiko Shimizu; Tsuguhito Ota; Masaru Sakurai; Hirofumi Misu; Seiichiro Kurita; Naoto Matsuzawa-Nagata; et al.Masahiro UchikataSeiji NakamuraRyo MatobaMotohiko TaninoKen-Ichi MatsubaraShuichi Kaneko Gene expression profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells reflect the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2007, 361, 379-384, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.006.

- Sayed Ali Sheikh; Role of Plasma Soluble Lectin-Like Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-1 and microRNA-98 in Severity and Risk of Coronary Artery Disease. Balkan Medical Journal 2021, 38, 13-22, 10.5152/balkanmedj.2021.20243.

- Yingchun Xu; Chunbo Miao; Jinzhen Cui; Xiaoli Bian; miR-92a-3p promotes ox-LDL induced-apoptosis in HUVECs via targeting SIRT6 and activating MAPK signaling pathway. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2020, 54, e9386, 10.1590/1414-431x20209386.

- Thomas Treiber; Nora Treiber; Gunter Meister; Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 20, 5-20, 10.1038/s41580-018-0059-1.

- Jacob O'brien; Heyam Hayder; Yara Zayed; Chun Peng; Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2018, 9, 402, 10.3389/fendo.2018.00402.

- J A Deiuliis; MicroRNAs as regulators of metabolic disease: pathophysiologic significance and emerging role as biomarkers and therapeutics. International Journal of Obesity 2015, 40, 88-101, 10.1038/ijo.2015.170.

- Zhihong Yang; Tyler Cappello; Li Wang; Emerging role of microRNAs in lipid metabolism. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2015, 5, 145-150, 10.1016/j.apsb.2015.01.002.

- Stefan L Ameres; Phillip D. Zamore; Diversifying microRNA sequence and function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2013, 14, 475-488, 10.1038/nrm3611.

- T. Desvignes; P. Batzel; E. Berezikov; K. Eilbeck; J.T. Eppig; M.S. McAndrews; A. Singer; J.H. Postlethwait; miRNA Nomenclature: A View Incorporating Genetic Origins, Biosynthetic Pathways, and Sequence Variants. Trends in Genetics 2015, 31, 613-626, 10.1016/j.tig.2015.09.002.

- Lyudmila F. Gulyaeva; Nicolay E. Kushlinskiy; Regulatory mechanisms of microRNA expression. Journal of Translational Medicine 2016, 14, 1-10, 10.1186/s12967-016-0893-x.

- Sharon A. Ross; Cindy D. Davis; The Emerging Role of microRNAs and Nutrition in Modulating Health and Disease. Annual Review of Nutrition 2014, 34, 305-336, 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105729.

- Felicia Carotenuto; Maria C. Albertini; Dario Coletti; Alessandra Vilmercati; Luigi Campanella; Zbigniew Darzynkiewicz; Laura Teodori; How Diet Intervention via Modulation of DNA Damage Response through MicroRNAs May Have an Effect on Cancer Prevention and Aging, an in Silico Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 752, 10.3390/ijms17050752.

- Andrea De Gottardi; Manlio Vinciguerra; Antonino Sgroi; Moulay Moukil; Florence Ravier-Dall'Antonia; Valerio Pazienza; Paolo Pugnale; Michelangelo Foti; Antoine Hadengue; Microarray analyses and molecular profiling of steatosis induction in immortalized human hepatocytes. Laboratory Investigation 2007, 87, 792-806, 10.1038/labinvest.3700590.

- Manlio Vinciguerra; Antonino Sgroi; Christelle Veyrat-Durebex; Laura Rubbia-Brandt; Leo H. Buhler; Michelangelo Foti; Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit the expression of tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) via microRNA-21 up-regulation in hepatocytes. Hepatology 2008, 49, 1176-1184, 10.1002/hep.22737.

- Omaima Ali; Hebatallah A. Darwish; Kamal M. Eldeib; Samy A. Abdel Azim; miR-26a Potentially Contributes to the Regulation of Fatty Acid and Sterol Metabolism In Vitro Human HepG2 Cell Model of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018, 8515343-11, 10.1155/2018/8515343.

- Anastasia Georgiadi; Sander Kersten; Mechanisms of Gene Regulation by Fatty Acids. Advances in Nutrition: An International Review Journal 2012, 3, 127-134, 10.3945/an.111.001602.

- Pilar Parra; Francisca Serra; Andreu Palou; Expression of Adipose MicroRNAs Is Sensitive to Dietary Conjugated Linoleic Acid Treatment in Mice. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e13005, 10.1371/journal.pone.0013005.

- Susanna Cirera; Malene Birck; Peter Kamp Busk; Merete Fredholm; Expression Profiles of miRNA-122 and Its Target CAT1 in Minipigs (Sus scrofa) Fed a High-Cholesterol Diet. Comparative Medicine 2010, 60, 136-141.

- Jiyun Ahn; Hyunjung Lee; Chang Hwa Chung; Taeyoul Ha; High fat diet induced downregulation of microRNA-467b increased lipoprotein lipase in hepatic steatosis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2011, 414, 664-669, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.120.

- Dionysios V. Chartoumpekis; Apostolos Zaravinos; Panos G. Ziros; Ralitsa P. Iskrenova; Agathoklis I. Psyrogiannis; Venetsana E. Kyriazopoulou; Ioannis G. Habeos; Differential Expression of MicroRNAs in Adipose Tissue after Long-Term High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity in Mice. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e34872, 10.1371/journal.pone.0034872.

- Laura Baselga-Escudero; Anna Arola-Arnal; Aïda Pascual-Serrano; Aleix Ribas-Latre; Ester Casanova; Josepa Salvado; Lluis Arola; Cinta Bladé; Chronic Administration of Proanthocyanidins or Docosahexaenoic Acid Reversess the Increase of miR-33a and miR-122 in Dyslipidemic Obese Rats. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69817, 10.1371/journal.pone.0069817.

- Valeria Nesca; Claudiane Guay; Cécile Jacovetti; Véronique Menoud; Marie-Line Peyot; D. Ross Laybutt; Marc Prentki; Romano Regazzi; Identification of particular groups of microRNAs that positively or negatively impact on beta cell function in obese models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 2203-2212, 10.1007/s00125-013-2993-y.

- Lidia Daimiel-Ruiz; Mercedes Klett-Mingo; Valentini Konstantinidou; Victor Micó; Juan Francisco Aranda; Belén García; Javier Martínez-Botas; Alberto Davalos; Carlos Fernández-Hernando; Jose M. Ordovás; et al. Dietary lipids modulate the expression of miR-107, an miRNA that regulates the circadian system. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2014, 59, 552-565, 10.1002/mnfr.201400616.

- Francisco J. Ortega; Mónica I. Cardona-Alvarado; Josep M. Mercader; José María Moreno-Navarrete; María Moreno; Mònica Sabater; Núria Fuentes-Batllevell; Enrique Ramírez-Chávez; Wifredo Ricart; Jorge Molina Torres; et al.Elva L. Pérez-LuqueJosé M. Fernández-Real Circulating profiling reveals the effect of a polyunsaturated fatty acid-enriched diet on common microRNAs. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2015, 26, 1095-1101, 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.05.001.

- Simona D'amore; Michele Vacca; Marica Cariello; Giusi Graziano; Andria D'orazio; Roberto Salvia; Rosa Cinzia Sasso; Carlo Sabbà; Giuseppe Palasciano; Antonio Moschetta; et al. Genes and miRNA expression signatures in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in healthy subjects and patients with metabolic syndrome after acute intake of extra virgin olive oil. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2016, 1861, 1671-1680, 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.07.003.

- Matthias J. Betz; Sven Enerbäck; Targeting thermogenesis in brown fat and muscle to treat obesity and metabolic disease. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2017, 14, 77-87, 10.1038/nrendo.2017.132.

- Jiyoung Kim; Meshail Okla; Anjeza Erickson; Timothy Carr; Sathish Kumar Natarajan; Soonkyu Chung; Eicosapentaenoic Acid Potentiates Brown Thermogenesis through FFAR4-dependent Up-regulation of miR-30b and miR-378. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 20551-20562, 10.1074/jbc.m116.721480.

- Won-Mo Yang; Kyung-Ho Min; Wan Lee; Induction of miR-96 by Dietary Saturated Fatty Acids Exacerbates Hepatic Insulin Resistance through the Suppression of INSR and IRS-1. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0169039, 10.1371/journal.pone.0169039.

- Annie Motard-Bélanger; Amélie Charest; Geneviève Grenier; Paul Paquin; Yvan Chouinard; Simone Lemieux; Patrick Couture; Benoît Lamarche; Study of the effect of trans fatty acids from ruminants on blood lipids and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 87, 593-599, 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.593.

- Véronique Desgagné; Renée Guérin; Simon-Pierre Guay; François Corbin; Patrick Couture; Benoit Lamarche; Luigi Bouchard; Changes in high-density lipoprotein-carried miRNA contribution to the plasmatic pool after consumption of dietarytransfat in healthy men. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 669-688, 10.2217/epi-2016-0177.

- Hualin Wang; Yang Shao; Fahu Yuan; Han Feng; Wang Hualin; Hongyu Zhang; ChaoDong Wu; Zhiguo Liu; Fish Oil Feeding Modulates the Expression of Hepatic MicroRNAs in a Western-Style Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Rat Model. BioMed Research International 2017, 2017, 1-11, 10.1155/2017/2503847.

- Cassandra E. Forsythe; Stephen D. Phinney; Maria Luz Fernandez; Erin E. Quann; Richard J. Wood; Doug M. Bibus; William J. Kraemer; Richard D. Feinman; Jeff S. Volek; Comparison of Low Fat and Low Carbohydrate Diets on Circulating Fatty Acid Composition and Markers of Inflammation. Lipids 2007, 43, 65-77, 10.1007/s11745-007-3132-7.

- Kevin L Fritsche; The Science of Fatty Acids and Inflammation. Advances in Nutrition 2015, 6, 293S-301S, 10.3945/an.114.006940.

- Ernst T. Rietschel; Teruo Kirikae; F. Ulrich Schade; Uwe Mamat; Günter Schmidt; Harald Loppnow; Artur J. Ulmer; Ulrich Zähringer; Ulrich Seydel; Franco Di Padova; et al.Max SchreierHelmut Brade Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. The FASEB Journal 1994, 8, 217-225, 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119492.

- Patrice D. Cani; Jacques Amar; Miguel Angel Iglesias; Marjorie Poggi; Claude Knauf; Delphine Bastelica; Audrey Neyrinck; Francesca Fava; Kieran Tuohy; Chantal Chabo; et al.Aurélie WagetEvelyne DelméeBéatrice CousinThierry SulpiceBernard ChamontinJean FerrieresJean-François TantiGlenn R. GibsonLouis CasteillaNathalie DelzenneMarie Christine AlessiRémy Burcelin Metabolic Endotoxemia Initiates Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761-1772, 10.2337/db06-1491.

- Clett Erridge; The capacity of foodstuffs to induce innate immune activation of human monocytesin vitrois dependent on food content of stimulants of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. British Journal of Nutrition 2010, 105, 15-23, 10.1017/s0007114510003004.

- Kiyoshi Takeda; Tsuneyasu Kaisho; Shizuo Akira; TOLL-LIKERECEPTORS. Annual Review of Immunology 2003, 21, 335-376, 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126.

- Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S.; Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol 1999, 162, 3749.

- Fabienne Laugerette; Cécile Vors; Alain Géloën; Marie-Agnès Chauvin; Christophe Soulage; Stéphanie Lambert-Porcheron; Noël Peretti; Maud Alligier; Rémy Burcelin; Martine Laville; et al.Hubert VidalMarie-Caroline Michalski Emulsified lipids increase endotoxemia: possible role in early postprandial low-grade inflammation. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2011, 22, 53-59, 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.11.011.

- Zheng Zheng; Yinlin Ge; Jinyu Zhang; Meilan Xue; Lin Dongliang; Dongliang Lin; Wenhui Ma; PUFA diets alter the microRNA expression profiles in an inflammation rat model. Molecular Medicine Reports 2015, 11, 4149-4157, 10.3892/mmr.2015.3318.