| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regina Duarte | + 1317 word(s) | 1317 | 2021-06-03 15:38:40 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1317 | 2021-06-07 03:37:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

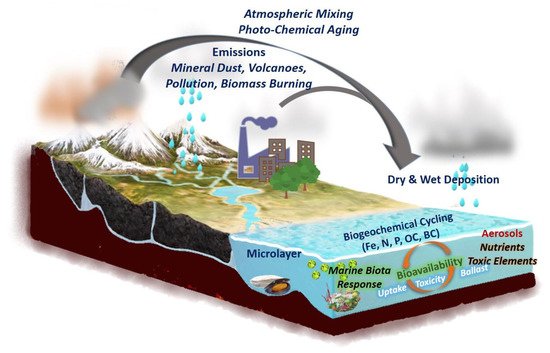

Atmospheric aerosol deposition (wet and dry) is an important source of macro and micronutrients (N, P, C, Si, and Fe) to the oceans. Most of the mass flux of air particles is made of fine mineral particles emitted from arid or semi-arid areas (e.g., deserts) and transported over long distances until deposition to the oceans. However, this atmospheric deposition is affected by anthropogenic activities, which heavily impacts the content and composition of aerosol constituents, contributing to the presence of potentially toxic elements (e.g., Cu). Under this scenario, the deposition of natural and anthropogenic aerosols will impact the biogeochemical cycles of nutrients and toxic elements in the ocean, also affecting (positively or negatively) primary productivity and, ultimately, the marine biota.

1. Introduction

Atmospheric aerosols play an important role in climate because they can modify, both directly and indirectly, the Earth’s radiative balance. Direct effects originate from the absorption and/or scattering of solar radiation by atmospheric aerosols, whereas indirect effects are mainly determined by the influence of aerosols on both cloud droplet and ice nuclei activation and the subsequent impact on cloud radiative properties and precipitation [1]. Aerosols can be emitted directly into the atmosphere (primary aerosols) from both natural (e.g., sea-salt, mineral aerosols (or dust), and volcanic dust) and anthropogenic sources (e.g., combustion of fossil fuels, waste and biomass burning, industrial activities, mining, and agricultural activities), or formed in the atmosphere (secondary aerosols) through gas-to-particle conversion processes (nucleation and condensation) of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and/or photochemical processing of primary aerosols (atmospheric aging) [1][2]. Due to this multitude of sources and formation processes, aerosols vary in composition and size, which grants them an important role in eliciting deleterious effects on air quality and human health.

Once in the atmosphere, aerosols can be transported over long distances and deposited onto terrestrial surfaces. Indeed, the lifetime of aerosols in the atmosphere is determined by wet and dry deposition, with wet deposition losses being typically estimated to account for the majority of submicron particle removal from the atmosphere [3][4]. Furthermore, wet deposition is eventually more important locally or regionally, close to aerosols emission sources, whereas dry deposition would be more important in areas far from emission sources. As far as the ocean is concerned, atmospheric deposition of aerosols can impact the biogeochemical cycles of several important nutrients in the ocean, especially Fe, N, and P [5], thus enhancing ocean productivity (Figure 1). The impact of atmospheric aerosol deposition to the upper ocean is certainly very dynamic, altering both the surface seawater chemistry and marine biological production.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram illustrating the aerosols sources (natural and anthropogenic), transport, and deposition onto marine ecosystems, inducing biotic responses. Upon deposition onto the upper ocean, aerosols can impact nutrient and toxic elements availability, ocean biogeochemistry, ocean productivity, and carbon cycling. The description of these topics can be seen in the relevant sections. Fe—iron; N—nitrogen; P—phosphorous; OC—organic carbon; BC—black carbon.

2. Mineral Dust Deposition onto the Upper Ocean

The literature shows the considerable effort that has been devoted to the quantification and identification of major dust source regions and transport pathways until deposition onto the upper ocean [6][7]. The long-lived isotope thorium-232 (232Th) has been used to quantify the lithogenic inputs into the oceans (e.g., [8][9][10]) since it is supplied by dust, whereas other isotopes (such as 234Th and 230Th) are produced uniformly throughout the ocean by radioactive decay of dissolved uranium (238U and 234U, respectively) [11].

In terms of the identification of major dust source regions and transport pathways, it has been possible to ascribe dust sources to natural and anthropogenic (primarily agricultural) origins, with the mineral dust sources accounting globally for up to 81% of the emissions (the remaining 19% is assigned to anthropogenic sources) [6][12], reaching almost 100% in hyper-arid regions according to MODIS data [12]. Chen and co-authors estimated that dust emissions from hyper-arid and arid regions contribute more than 97% to the global mineral dust emissions with emission fluxes reaching up to 50 μg·m−2·s−1 [12]. Since the mineral dust can be transported thousands of miles over the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and deliver important amounts of nutrients to the LNLC Atlantic and Pacific gyres, it could play a significant role in primary production in those marine regions [13][14][15].

Due to the elemental composition of the earth crust, the atmospheric input of dust particles constitutes a major source of nutrients to the upper ocean, including Fe, N, and P. Of these, Fe has received much attention, driven by the realization that Fe can be a limiting nutrient in large areas of the global ocean [16]. Given its importance for primary productivity in the ocean [14], numerous studies have addressed the release of Fe from dust particles in seawater.

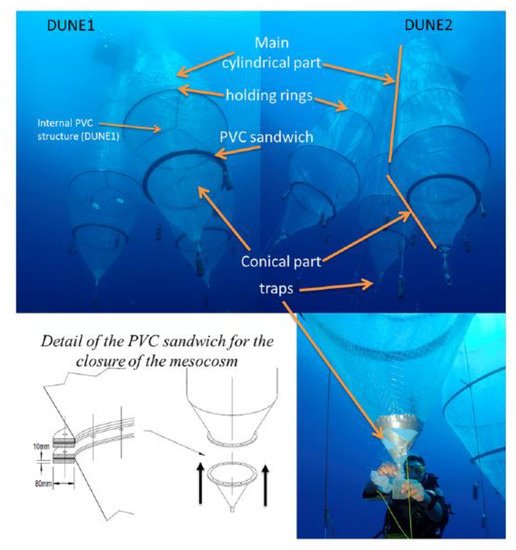

Under low-DOM conditions (i.e., in mixing periods or in low-productive areas), the absence of aggregation allows a strong and transient increase in dissolved Fe concentration to occur prior to being removed through adsorption on sinking particles [17]. Additional studies addressing the impact of atmospheric dust deposition on an oligotrophic ecosystem, i.e., the Mediterranean Sea, were conducted within the framework of the project “DUst experiment in a low-Nutrient, low-chlorophyll Ecosystem” (DUNE) [18]. Experiments involved the addition of dust onto large clean mesocosms (Figure 2), which allowed for the quantification of the dissolution and adsorption processes of dissolved Fe occurring from (or at) mineral particles surface [19].

Figure 2. Pictures and schematic representation of the mesocosms underwater developed within the framework of DUNE project. (Reprinted from the work of Guieu et al. [18], under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License).

3. Deposition of Anthropogenic Aerosols to the Upper Ocean

The deposition (dry and wet) of atmospheric anthropogenic N, S, P, and C (organic and black C) onto the upper ocean has become a well-known environmental problem: it can alter not only the chemistry of surface seawater but also the marine biological production. This is even more critical when some studies suggest that anthropogenic fugitive, combustion, and industrial dust emissions are underrepresented in PM2.5 emission global inventories by at least 10% based on GEOS-Chem simulations [20].

Atmospheric deposition of organic carbon (OC) and black carbon (BC) into the oceans is also important to the global carbon budget. Based on monthly satellite measurements of aerosol size distribution, temperature, and wind speed, Jurado et al. [21] suggested an important spatial and temporal variability of the atmosphere–ocean exchanges of OC and BC at different scales.

Recent studies have shown an increase in anthropogenic air pollutants (e.g., Mn, Pb, Zn, SO42−, NO3−) in the North Pacific Ocean transported by aerosols from pollution events in eastern Asian countries and the Taklamakan and Mongolian deserts [e.g., [22][23].

Research on the impact of atmospheric BC deposition into the Arctic Ocean has also been receiving increasing attention. It is well known that the Arctic region is especially sensitive to global changes and increases in BC emissions may contribute to the amplification of Arctic warming. It has been reported that atmospherically deposited BC becomes available into the Arctic Ocean with the increasing melting of sea ice during summer, thus influencing the abundance of dissolved BC in the surface waters [24][25]. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that anthropogenic aerosol organic matter is the main source of fossil DOM in glacier waters and runoff [26].

4. Effects of Atmospheric Deposition on Marine Biota

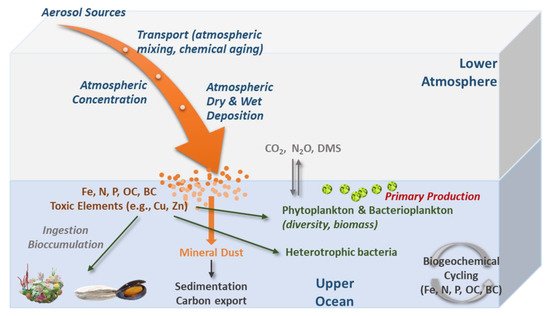

Atmospheric deposition can favor the growth of some planktonic species (according to their nutritional needs), as it is a source of inorganic nutrients and organic matter [27][28][29] (Figure 3). The essential elements that limit marine phytoplankton productivity include C, N, P, and Fe, in an average proportion of 106 C:16 N:1 P:0.0075 Fe, known as the Redfield ratio [30]. Mineral dust deposition provides a source of these elements to the open sea surface waters and can have important impacts on marine biogeochemical cycles and possibly influence the climate [31][7][32][33][34][35].

Figure 3. Conceptual diagram illustrating the main processes of atmospheric aerosols (wet and dry) deposition and main changes occurring in the marine biota.

References

- Pöschl, U. Atmospheric Aerosols: Composition, Transformation, Climate and Health Effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7520–7540.

- Tomasi, C.; Lupi, A. Primary and Secondary Sources of Atmospheric Aerosol. In Atmospheric Aerosols; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–86.

- Emerson, E.W.; Katich, J.M.; Schwarz, J.P.; McMeeking, G.R.; Farmer, D.K. Direct Measurements of Dry and Wet Deposition of Black Carbon Over a Grassland. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 12277–12290.

- Emerson, E.W.; Hodshire, A.L.; DeBolt, H.M.; Bilsback, K.R.; Pierce, J.R.; McMeeking, G.R.; Farmer, D.K. Revisiting particle dry deposition and its role in radiative effect estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26076–26082.

- De Leeuw, G.; Guieu, C.; Arneth, A.; Bellouin, N.; Bopp, L.; Boyd, P.W.; van der Gon, H.A.C.D.; Desboeufs, K.V.; Dulac, F.; Facchini, M.C.; et al. Ocean–Atmosphere Interactions of Particles. In Ocean-Atmosphere Interactions of Gases and Particles; Liss, P.C., Johnson, M.T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 171–246. ISBN 9783642256431.

- Ginoux, P.; Prospero, J.M.; Gill, T.E.; Hsu, N.C.; Zhao, M. Global-scale attribution of anthropogenic and natural dust sources and their emission rates based on MODIS Deep Blue aerosol products. Rev. Geophys. 2012, 50, 3005.

- Schulz, M.; Prospero, J.M.; Baker, A.R.; Dentener, F.; Ickes, L.; Liss, P.S.; Mahowald, N.M.; Nickovic, S.; García-Pando, C.P.; Rodríguez, S.; et al. Atmospheric Transport and Deposition of Mineral Dust to the Ocean: Implications for Research Needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 10390–10404.

- Kienast, S.S.; Winckler, G.; Lippold, J.; Albani, S.; Mahowald, N.M. Tracing dust input to the global ocean using thorium isotopes in marine sediments: ThoroMap. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2016, 30, 1526–1541.

- Hayes, C.T.; Anderson, R.F.; Fleisher, M.Q.; Serno, S.; Winckler, G.; Gersonde, R. Quantifying lithogenic inputs to the North Pacific Ocean using the long-lived thorium isotopes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 383, 16–25.

- Hsieh, Y.T.; Henderson, G.M.; Thomas, A.L. Combining seawater 232Th and 230Th concentrations to determine dust fluxes to the surface ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011, 312, 280–290.

- Anderson, R.F.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Fleisher, M.Q.; Hayes, C.T.; Huang, K.F.; Kadko, D.; Lam, P.J.; Landing, W.M.; Lao, Y.; et al. How well can we quantify dust deposition to the ocean? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374.

- Chen, S.; Jiang, N.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zang, Z.; Huang, K.; Xu, X.; Wei, Y.; Guan, X.; et al. Quantifying contributions of natural and anthropogenic dust emission from different climatic regions. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 191, 94–104.

- Marañén, E.; Fernández, A.; Mouriño-Carballido, B.; MartÍnez-GarcÍa, S.; Teira, E.; Cermeño, P.; Chouciño, P.; Huete-Ortega, M.; Fernández, E.; Calvo-DÍaz, A.; et al. Degree of oligotrophy controls the response of microbial plankton to Saharan dust. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 2339–2352.

- Ridame, C.; Dekaezemacker, J.; Guieu, C.; Bonnet, S.; L’Helguen, S.; Malien, F. Contrasted Saharan dust events in LNLC environments: Impact on nutrient dynamics and primary production. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 4783–4800.

- Franchy, G.; Ojeda, A.; López-Cancio, J.; Hernández-León, S. Plankton community response to Saharan dust fertilization in subtropical waters off the Canary Islands. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2013, 10, 17275–17307.

- Martin, J.H.; Gordon, R.M.; Fitzwater, S.E. The case for iron. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1991, 36, 1793–1802.

- Bressac, M.; Guieu, C. Post-depositional processes: What really happens to new atmospheric iron in the ocean’s surface? Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2013, 27, 859–870.

- Guieu, C.; Dulac, F.; Ridame, C.; Pondaven, P. Introduction to project DUNE, a DUst experiment in a low Nutrient, low chlorophyll Ecosystem. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 425–442.

- Wagener, T.; Guieu, C.; Leblond, N. Effects of dust deposition on iron cycle in the surface Mediterranean Sea: Results from a mesocosm seeding experiment. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 3769–3781.

- Philip, S.; Martin, R.V.; Snider, G.; Weagle, C.L.; Van Donkelaar, A.; Brauer, M.; Henze, D.K.; Klimont, Z.; Venkataraman, C.; Guttikunda, S.K.; et al. Anthropogenic fugitive, combustion and industrial dust is a significant, underrepresented fine particulate matter source in global atmospheric models. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 044018.

- Jurado, E.; Dachs, J.; Duarte, C.M.; Simó, R. Atmospheric deposition of organic and black carbon to the global oceans. Atmos. Environ. 2008, 42, 7931–7939.

- Fu, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Q. The influence of continental air masses on the aerosols and nutrients deposition over the western North Pacific. Atmos. Environ. 2018, 172, 1–11.

- Kim, I.N.; Lee, K.; Gruber, N.; Karl, D.M.; Bullister, J.L.; Yang, S.; Kim, T.W. Increasing anthropogenic nitrogen in the North Pacific Ocean. Science 2014, 346, 1102–1106.

- Doherty, S.J.; Warren, S.G.; Grenfell, T.C.; Clarke, A.D.; Brandt, R.E. Light-absorbing impurities in Arctic snow. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2010, 10, 11647–11680.

- Fang, Z.; Yang, W.; Chen, M.; Zheng, M.; Hu, W. Abundance and sinking of particulate black carbon in the western Arctic and Subarctic Oceans. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–11.

- Stubbins, A.; Hood, E.; Raymond, P.A.; Aiken, G.R.; Sleighter, R.L.; Hernes, P.J.; Butman, D.; Hatcher, P.G.; Striegl, R.G.; Schuster, P.; et al. Anthropogenic aerosols as a source of ancient dissolved organic matter in glaciers. Nat. Geosci. 2012, 5, 198–201.

- Bikkina, P.; Sarma, V.V.S.S.; Kawamura, K.; Bikkina, S. Dry-deposition of inorganic and organic nitrogen aerosols to the Arabian Sea: Sources, transport and biogeochemical significance in surface waters. Mar. Chem. 2021, 231, 103938.

- Pinhassi, J.; Gómez-Consarnau, L.; Alonso-Sáez, L.; Sala, M.; Vidal, M.; Pedrós-Alió, C.; Gasol, J. Seasonal changes in bacterioplankton nutrient limitation and their effects on bacterial community composition in the NW Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2006, 44, 241–252.

- Gallisai, R.; Peters, F.; Volpe, G.; Basart, S.; Baldasano, J.M. Saharan Dust Deposition May Affect Phytoplankton Growth in the Mediterranean Sea at Ecological Time Scales. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110762.

- Bristow, L.A.; Mohr, W.; Ahmerkamp, S.; Kuypers, M.M.M. Nutrients that limit growth in the ocean. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R474–R478.

- Paytan, A.; Mackey, K.R.M.; Chen, Y.; Lima, I.D.; Doney, S.C.; Mahowald, N.; Labiosa, R.; Post, A.F. Toxicity of atmospheric aerosols on marine phytoplankton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4601–4605.

- Jickells, T.D.; An, Z.S.; Andersen, K.K.; Baker, A.R.; Bergametti, C.; Brooks, N.; Cao, J.J.; Boyd, P.W.; Duce, R.A.; Hunter, K.A.; et al. Global iron connections between desert dust, ocean biogeochemistry, and climate. Science 2005, 308, 67–71.

- Mahowald, N.; Jickells, T.D.; Baker, A.R.; Artaxo, P.; Benitez-Nelson, C.R.; Bergametti, G.; Bond, T.C.; Chen, Y.; Cohen, D.D.; Herut, B.; et al. Global distribution of atmospheric phosphorus sources, concentrations and deposition rates, and anthropogenic impacts. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22.

- Baker, A.R.; Kelly, S.D.; Biswas, K.F.; Witt, M.; Jickells, T.D. Atmospheric deposition of nutrients to the Atlantic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30.

- Mahowald, N.M.; Baker, A.R.; Bergametti, G.; Brooks, N.; Duce, R.A.; Jickells, T.D.; Kubilay, N.; Prospero, J.M.; Tegen, I. Atmospheric global dust cycle and iron inputs to the ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2005, 19.