| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alexander E. Berezin | + 2630 word(s) | 2630 | 2021-05-27 08:11:20 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2630 | 2021-06-01 11:38:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

Heart failure (HF) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have a synergistic effect on cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality in patients with established CV disease (CVD).

1. Introduction

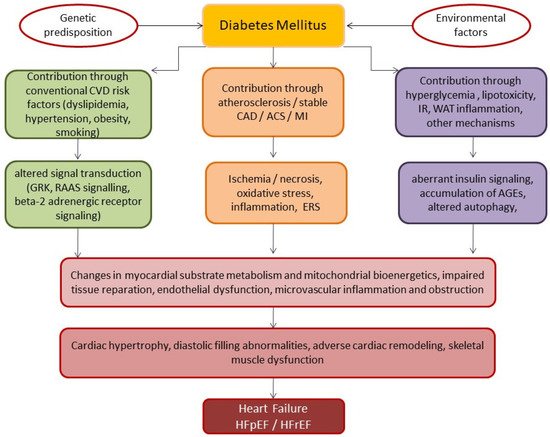

2. Basic Underlying Mechanisms of HF Development in Diabetics

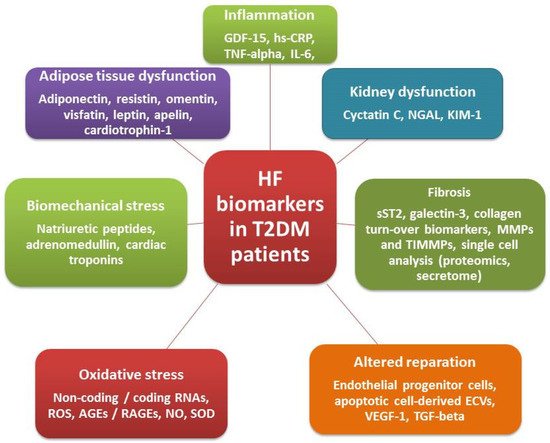

3. Biomarkers in Diabetics with Known HF

|

Strategy |

Biomarkers |

ESC, 2016 |

ACC/AHA/HFSA, 2017 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COR |

LOE |

Phenotype of HF |

COR |

LOE |

Phenotype of HF |

||

|

Diagnosis |

BNP/NT-proBNP/MR-proANP * |

I |

A |

AHF, HFpEF, HFmrEF |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

|

Risk of in-hospital death |

BNP/NT-proBNP |

I |

C |

AHF |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

|

hs-cTr |

I |

C |

AHF |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

|

|

Risk of recurrent hospital admission |

BNP/NT-proBNP |

- |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

||

|

Risk of post-discharged death |

BNP/NT-proBNP |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

I |

A |

AHF, CHF |

|

hs-cTr |

I |

C |

AHF, CHF |

I |

IIa |

AHF, CHF |

|

|

Galectin-3 |

- |

IIb |

B |

AHF, CHF |

|||

|

sST2 |

- |

IIb |

B |

AHF, CHF |

|||

|

Prevention of HF onset |

BNP/NT-proBNP |

- |

IIa |

B |

AHF, CHF |

||

|

Guided therapy |

BNP/NT-proBNP |

- |

I |

A |

HFrEF/HFpEF |

||

|

Biomarkers |

Underlying Pathophysiological Mechanisms |

Possible Application for HF Phenotype |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NPs |

Biomechanical stress |

HFrEF, HFpEF |

Available for diagnosis, risk stratification, prognosis, and point-to-care therapy |

High serum level variability, variable cut-off points in patients with AF, CKD, AO, prediction in HFrEF is higher than HFpEF |

|

hs-cTn |

Myocardial injury |

Manly HFrEF |

Available for risk stratification and prognosis |

No add-on prediction to NPs |

|

Mid-regional-pro-adrenomedullin |

Neurohumoral activation |

HFrEF, HFpEF |

Better than NPs in predicting short-term mortality in acute HF |

No superiority to NPs in predictive ability among chronic HFrEF/HFpEF |

|

hs-CRP, IL-6 |

Inflammation |

HFrEF, HFpEF |

Prediction of all-cause mortality, CVD, HF-related events |

Not suitable for point-of-care therapy, no ability to increase predictive ability of NPs, not recommended by reputed medical societies |

|

GDF-15 |

Inflammation |

HFrEF, HFpEF |

Available for improving predictive ability of NPs, suitable for multiple biomarker strategy and point-of-care therapy |

High cost, not recommended by reputed medical societies |

|

sST2, galectin-3 |

Fibrosis/inflammation |

HFpEF |

Better than NPs for predicting mortality and HF-related events in non-HF patients, low individual serum level variability |

High cost |

|

Collagen turn-over biomarkers |

Fibrosis |

HFpEF |

Available for risk stratification and prognosis |

High cost, not recommended by reputed medical societies |

Abbreviations: AO, abdominal obesity; AF, atrial fibrillation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NPs, natriuretic peptides; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; sST2, soluble suppressor tumorigenisity-2; GDF-15, growth differential factor-15; IL, interleukin; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

4. Multiple Biomarker Strategies

5. Point-of-Care Clinical Diagnostics in HF

References

- Cho, N.; Shaw, J.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; Fernandes, J.D.R.; Ohlrogge, A.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281.

- Glovaci, D.; Fan, W.; Wong, N.D. Epidemiology of Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2019, 21, 21.

- Ziaeian, B.; Fonarow, B.Z.G.C. Epidemiology and aetiology of heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 368–378.

- Lehrke, M.; Marx, N. Diabetes Mellitus and Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, S37–S47.

- Thrainsdottir, I.S.; Aspelund, T.; Thorgeirsson, G.; Gudnason, V.; Hardarson, T.; Malmberg, K.; Sigurdsson, G.; Rydén, L. The Association Between Glucose Abnormalities and Heart Failure in the Population-Based Reykjavik Study. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 612–616.

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Colvin, M.M.; Drazner, M.H.; Filippatos, G.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017, 136, e137–e161.

- Kenny, H.C.; Abel, E.D. Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 121–141.

- Berezin, A.E.; Berezin, A.A.; Lichtenauer, M. Emerging Role of Adipocyte Dysfunction in Inducing Heart Failure Among Obese Patients With Prediabetes and Known Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 583175.

- Kato, E.T.; Silverman, M.G.; Mosenzon, O.; Zelniker, T.A.; Cahn, A.; Furtado, R.H.M.; Kuder, J.; Murphy, S.A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Leiter, L.A.; et al. Effect of Dapagliflozin on Heart Failure and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2019, 139, 2528–2536.

- Thein, D.; Christiansen, M.N.; Mogensen, U.M.; Bundgaard, J.S.; Rørth, R.; Madelaire, C.; Fosbøl, E.L.; Schou, M.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.; et al. Add-on therapy in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes at moderate cardiovascular risk: A nationwide study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 1–11.

- Lytvyn, Y.; Bjornstad, P.; Udell, J.A.; Lovshin, J.A.; Cherney, D.Z. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibition in Heart Failure. Circulation 2017, 136, 1643–1658.

- Marsico, F.; Gargiulo, P.; Marra, A.M.; Parente, A.; Paolillo, S. Glucose Metabolism Abnormalities in Heart Failure Patients. Heart Fail. Clin. 2019, 15, 333–340.

- Berezin, A.E. Circulating Cardiac Biomarkers in Diabetes Mellitus: A New Dawn for Risk Stratification—A Narrative Review. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 1271–1291.

- Lee, W.-S.; Kim, J. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Where we are and where we are going. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 404–421.

- Udell, J.A.; Steg, P.G.; Scirica, B.M.; Eagle, K.; Ohman, E.M.; Goto, S.; Alsheikh-Ali, A.A.; Porath, A.; Corbalan, R.; Umez-Eronini, A.A.; et al. Metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or both and cardiovascular risk in outpatients with or at risk for atherothrombosis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2014, 21, 1531–1540.

- Braunwald, E. Diabetes, heart failure, and renal dysfunction: The vicious circles. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 62, 298–302.

- Cui, R.; Sun, S.Q.; Zhong, N.; Xu, M.X.; Cai, H.D.; Zhang, G.; Qu, S.; Sheng, H. The relationship between atherosclerosis and bone mineral density in patients with type 2 diabetes depends on vascular calcifications and sex. Osteoporos. Int. 2020, 31, 1135–1143.

- Dillmann, W.H. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1160–1162.

- Kanamori, H.; Takemura, G.; Goto, K.; Tsujimoto, A.; Mikami, A.; Ogino, A.; Watanabe, T.; Morishita, K.; Okada, H.; Kawasaki, M.; et al. Autophagic adaptations in diabetic cardiomyopathy differ between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1146–1160.

- Li, S.; Liang, M.; Gao, D.; Su, Q.; Laher, I. Changes in Titin and Collagen Modulate Effects of Aerobic and Resistance Exercise on Diabetic Cardiac Function. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2019, 12, 404–414.

- Hamdani, N.; Franssen, C.; Lourenço, A.; Falcão-Pires, I.; Fontoura, D.; Leite, S.; Plettig, L.; López, B.; Ottenheijm, C.A.; Becher, P.M.; et al. Myocardial Titin Hypophosphorylation Importantly Contributes to Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction in a Rat Metabolic Risk Model. Circ. Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 1239–1249.

- Feng, B.; Chen, S.; Chiu, J.; George, B.; Chakrabarti, S. Regulation of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in diabetes at the transcriptional level. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2008, 294, E1119–E1126.

- Fender, A.C.; Pavic, G.; Drummond, G.R.; Dusting, G.J.; Ritchie, R.H. Unexpected anti-hypertrophic responses to low-level stimulation of protease-activated receptors in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2014, 387, 1001–1007.

- Rosenkranz, A.C.; Hood, S.G.; Woods, R.L.; Dusting, G.J.; Ritchie, R.H. B-type natriuretic peptide prevents acute hypertrophic responses in the diabetic rat heart: Importance of cyclic GMP. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2389–2395.

- Sundgren, N.C.; Giraud, G.D.; Schultz, J.M.; Lasarev, M.R.; Stork, P.J.S.; Thornburg, K.L. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphoinositol-3 kinase mediate IGF-1 induced proliferation of fetal sheep cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 285, R1481–R1489.

- Mehrhof, F.B.; Müller, F.-U.; Bergmann, M.W.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Schmitz, W.; Dietz, R.; Von Harsdorf, R. In Cardiomyocyte Hypoxia, Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I-Induced Antiapoptotic Signaling Requires Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH-Kinase-Dependent and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Dependent Activation of the Transcription Factor cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein. Circulation 2001, 104, 2088–2094.

- Bando, Y.K.; Murohara, T. Diabetes-Related Heart Failure. Circ. J. 2014, 78, 576–583.

- Díez, J.; González, A.; Kovacic, J.C. Myocardial Interstitial Fibrosis in Nonischemic Heart Disease, Part 3/4. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2204–2218.

- Lam, C.S. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: An expression of stage B heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2015, 12, 234–238.

- Passino, C.; Barison, A.; Vergaro, G.; Gabutti, A.; Borrelli, C.; Emdin, M.; Clerico, A. Markers of fibrosis, inflammation, and remodeling pathways in heart failure. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 443, 29–38.

- González, A.; López, B.; Ravassa, S.; José, G.S.; Díez, J. The complex dynamics of myocardial interstitial fibrosis in heart failure. Focus on collagen cross-linking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2019, 1866, 1421–1432.

- Berezin, A.E. Endogenous vascular repair system in cardiovascular disease: The role of endothelial progenitor cells. Australas. Med. J. 2019, 12, 42–48.

- Battiprolu, P.K.; Hojayev, B.; Jiang, N.; Wang, Z.V.; Luo, X.; Iglewski, M.; Shelton, J.M.; Gerard, R.D.; Rothermel, B.A.; Gillette, T.G.; et al. Metabolic stress–induced activation of FoxO1 triggers diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1109–1118.

- Qi, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Thomas, C.; Wu, Y.; Kumar, R.; Baker, K.M.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Guo, S. Activation of Foxo1 by Insulin Resistance Promotes Cardiac Dysfunction and -Myosin Heavy Chain Gene Expression. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 198–208.

- Liu, F.; Song, R.; Feng, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.-Y.; et al. Upregulation of MG53 Induces Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Through Transcriptional Activation of Peroxisome Proliferation-Activated Receptor α. Circulation 2015, 131, 795–804.

- Wu, H.-K.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, C.-M.; Hu, X.; Fang, M.; Yao, Y.; Jin, L.; Chen, G.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, S.; et al. Glucose-Sensitive Myokine/Cardiokine MG53 Regulates Systemic Insulin Response and Metabolic Homeostasis. Circulation 2019, 139, 901–914.

- Bugger, H.; Abel, E.D. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 660–671.

- Zarich, S.W.; Arbuckle, B.E.; Cohen, L.R.; Roberts, M.; Nesto, R.W. Diastolic abnormalities in young asymptomatic diabetic patients assessed by pulsed Doppler echocardiography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1988, 12, 114–120.

- Poirier, P.; Bogaty, P.; Philippon, F.; Garneau, C.; Fortin, C.; Dumesnil, J.-G. Preclinical diabetic cardiomyopathy: Relation of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction to cardiac autonomic neuropathy in men with uncomplicated well-controlled type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 2003, 52, 1056–1061.

- Ofstad, A.P.; Urheim, S.; Dalen, H.; Orvik, E.; Birkeland, K.I.; Gullestad, L.; Fagerland, M.W.; Johansen, O.E.; Aakhus, S. Identification of a definite diabetic cardiomyopathy in type 2 diabetes by comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation: A cross-sectional comparison with non-diabetic weight-matched controls. J. Diabetes 2015, 7, 779–790.

- Kocabaş, U.; Yılmaz, Ö.; Kurtoğlu, V. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: Acute and reversible left ventricular systolic dysfunction due to cardiotoxicity of hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state-a case report. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2019, 3, ytz049.

- Wold, L.E.; Ceylan-Isik, A.F.; Fang, C.X.; Yang, X.; Li, S.-Y.; Sreejayan, N.; Privratsky, J.R.; Ren, J. Metallothionein alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: Role of Ca2+ cycling proteins, NADPH oxidase, poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase and myosin heavy chain isozyme. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 1419–1429.

- Jia, G.; Hill, M.A.; Sowers, J.R. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 624–638.

- Yu, X.; Deng, L.; Wang, D.; Li, N.; Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Yuan, J.; Gao, X.; Liao, M.; Wang, M.; et al. Mechanism of TNF-α autocrine effects in hypoxic cardiomyocytes: Initiated by hypoxia inducible factor 1α, presented by exosomes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 53, 848–857.

- Guo, C.A.; Guo, S. Insulin receptor substrate signaling controls cardiac energy metabolism and heart failure. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 233, R131–R143.

- Berezin, A.E.; Berezin, A.A. Extracellular Endothelial Cell-Derived Vesicles: Emerging Role in Cardiac and Vascular Remodeling in Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 47.

- Sarhene, M.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Acheampong, E.; Zhengcan, Z.; Xiaoyan, Q.; Yunsheng, X.; et al. Biomarkers in heart failure: The past, current and future. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 867–903.

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975.

- Chow, S.L.; Maisel, A.S.; Anand, I.; Bozkurt, B.; De Boer, R.A.; Felker, G.M.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greenberg, B.; Januzzi, J.L.; Kiernan, M.S.; et al. Role of Biomarkers for the Prevention, Assessment, and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e1054–e1091.

- Ibrahim, N.E.; Januzzi, J.L. Established and Emerging Roles of Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 614–629.

- Butler, J.; Packer, M.; Greene, S.J.; Fiuzat, M.; Anker, S.D.; Anstrom, K.J.; Carson, P.E.; Cooper, L.B.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hernandez, A.F.; et al. Heart Failure End Points in Cardiovascular Outcome Trials of Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Circulation 2019, 140, 2108–2118.

- Suthahar, N.; Meijers, W.C.; Brouwers, F.P.; Heerspink, H.J.; Gansevoort, R.T.; Van Der Harst, P.; Bakker, S.J.; De Boer, R.A. Heart failure and inflammation-related biomarkers as predictors of new-onset diabetes in the general population. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 250, 188–194.

- Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Gao, C. Potential biomarkers for heart failure. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 9467–9474.

- Catalina, M.O.-S.; Redondo, P.C.; Granados, M.P.; Cantonero, C.; Sanchez-Collado, J.; Albarran, L.; Lopez, J.J. New Insights into Adipokines as Potential Biomarkers for Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 4119–4144.

- Berezin, A.E. Circulating Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1067, 89–108.

- Topf, A.; Mirna, M.; Ohnewein, B.; Jirak, P.; Kopp, K.; Fejzic, D.; Haslinger, M.; Motloch, L.J.; Hoppe, U.C.; Berezin, A.; et al. The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Value of Multimarker Analysis in Heart Failure. An Approach to Biomarker-Targeted Therapy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 579567.

- Düngen, H.-D.; Tscholl, V.; Obradovic, D.; Radenovic, S.; Matic, D.; Bright, L.M.; Tahirovic, E.; Marx, A.; Inkrot, S.; Hashemi, D.; et al. Prognostic performance of serial in-hospital measurements of copeptin and multiple novel biomarkers among patients with worsening heart failure: Results from the MOLITOR study. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 288–296.

- Zhang, M.; Meng, Q.; Qi, X.; Han, Q.; Qi, X.; Wang, F.; Du, B. Comparison of multiple biomarkers for mortality prediction in patients with acute heart failure of ischemic and nonischemic etiology. Biomarkers Med. 2018, 12, 1207–1217.

- Pandey, A.; Vaduganathan, M.; Patel, K.V.; Ayers, C.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Carnethon, M.; DeFilippi, C.; McGuire, D.K.; Khan, S.S.; et al. Biomarker-Based Risk Prediction of Incident Heart Failure in Pre-Diabetes and Diabetes. JACC Heart Fail. 2021, 9, 215–223.

- Berezin, A.E.; Kremzer, A.A.; Samura, T.; Berezina, T. Altered signature of apoptotic endothelial cell-derived microvesicles predicts chronic heart failure phenotypes. Biomarkers Med. 2019, 13, 737–750.