| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shuai Hou | + 4435 word(s) | 4435 | 2021-05-20 04:37:52 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -6 word(s) | 4429 | 2021-06-01 11:27:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

The oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is the efficiency-determining half-reaction process of high-demand, electricity-driven water splitting due to its sluggish four-electron transfer reaction. Tremendous effects on developing OER catalysts with high activity and strong acid-tolerance at high oxidation potentials have been made for proton-conducting polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysis (PEMWE), which is one of the most promising future hydrogen-fuel-generating technologies. Electrochemical water splitting involves two heterogeneous multi-step half-reactions, which are referred to as the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER). An important frontier in OER electrocatalysis research is the development of the rational design of catalysts. Most of the excellent OER catalysts with high activity and durability are not stable in acidic solutions. They are easily oxidized and decomposed in a strong acid system, which is one of the indispensable working conditions for PEMWE. Outstanding OER electrocatalysts should have excellent intrinsic activity and sufficient active sites, and these requirements are generally combined with simplicity and controllability.

1. Background

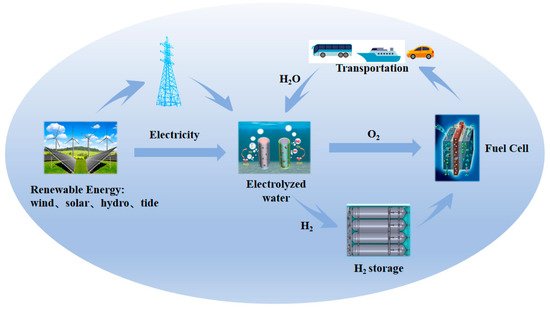

Searching for sustainable, clean, and highly efficient energy is the main method for solving the energy crisis and environmental pollution problems brought about by the first and second industrial revolutions, which have built a modern and prosperous society based on carbon-based fuels [1][2][3][4]. Human actions have led to the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere rising rapidly and exceeding 400 ppm currently, mostly originating from the burning of coal, oil, and gas [2][5]. The application of wind and solar power and other types of renewable electricity generation technologies seems to be an efficient way to fulfill the requirement of an energy revolution [6][7][8]. However, they are strongly intermittent in nature due to diurnal or seasonal variations [9]. Converting their energy to a zero-emission chemical energy carrier such as hydrogen is an alternative that can achieve versatile utilization, such as clean heating or electricity at a later stage, on account of the high energy density of hydrogen [5][10][11][12]. Therefore, an increasing number of sustainable pathways for energy conversion and storage technologies, including water electrolysis, batteries, and fuel cells, have been proposed and extensively investigated [5][13][14][15]. Proton exchange membrane water electrolysis (PEMWE) operating in acidic environments has offered an effective way to produce sustainable, high-purity hydrogen through targeted electrochemical reactions since the 1960s [16] (Figure 1). PEMWE has the advantages of a faster dynamic response, a higher current density, and lower crossover of gases and is considered to be the basis of a hydrogen society in the future [17][18][19].

Figure 1. Schematic of sustainable pathways for energy conversion and storage based on electrocatalysis.

Electrochemical water splitting involves two heterogeneous multi-step half-reactions, which are referred to as the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and the anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [20][21]. Owing to the inherent energy barrier, the practical operating voltage of commercial water electrolyzers is higher than the theoretical 1.23 V (versus a reversible hydrogen electrode) under the standard conditions (298 K and 1 atm) [22][23]. For example, industrial electrolytic water generally maintains the external voltage at 1.8~2.0 V [16]. Typically, the descriptor of overpotential is used to show the difference between the thermodynamic potential and the practical potential required to drive the electrochemical reaction [24]. The overpotential mainly comes from the electrochemical polarization on the anode side (ηa) and cathode side (ηc) and the ohmic polarization caused by other resistors (ηother) [25]. Comparing ηa and ηother, the intrinsically sluggish kinetics of the OER involving a four electron–proton coupled reaction (Equation (1)) hampers the overall water-splitting process [16][26].

One solution to this conundrum is to develop suitable catalysts with high efficiency and low overpotential [27]. However, most of the excellent OER catalysts with high activity and durability are not stable in acidic solutions [28]. They are easily oxidized and decomposed in a strong acid system, which is one of the indispensable working conditions for PEMWE [29]. Currently, the iridium (Ir) and ruthenium (Ru)-based electrocatalysts are regarded as the state-of-the-art commercial electrocatalysts for the OER [30][31]. Compared with other catalysts, they exhibit excellent OER catalytic activity due to their inherent promising activity, even if severe corrosion still exists under strong acid working conditions [32]. This provides a driving force for the vast majority of studies on the modifications of these electrocatalysts, including composition, structure, and morphology optimizations [23][33][34][35]. Outstanding OER electrocatalysts should have excellent intrinsic activity and sufficient active sites [18], and these requirements are generally combined with simplicity and controllability. In this regard, optimizations of the reaction energy barrier, electronic conductivity, and reaction surface area of the OER electrocatalysts are of great importance [18][36][37]. The transport efficiencies of electrons, ions, and produced oxygen are directly related to the number of channels, which depend on rational surface/interface engineering through nanostructural modifications, such as pore size control and construction of a multi-stage structure [33][38]. The nanostructures include zero-dimensional nanoclusters, nanoparticles, nanocages, and nanoframes [39]; one-dimensional nanotubes and nanowires [40]; two-dimensional nanosheets [41]; and three-dimensional nanowire networks, aerogels, etc. [42][43]. Moreover, simple and effective surface/interface engineering techniques have been diversified for adjusting the surface atoms, electronic structures, interfacial stresses, and bridge bonds, such as doping elements, tailoring the coordination environment, and loading with active materials [43][44][45][46].

Although Ru/Ir-based electrocatalysts have indeed shown good OER performance, they are still far from ideal OER electrocatalysts in terms of activity and are not completely stable at high oxidative potentials [17][47]. A growing body of evidence shows that Ru-based OER catalysts dissolve extensively during the electrocatalytic process [32]. This is because the onset potential of Ru-based catalysts is consistent with the corrosion potential of the metal Ru [48]. Ir-based catalysts also suffer similar degradation issues [49]. During the long-term catalytic process, rutile oxide of IrOx will transition to other kinds of phases that are soluble in acid media [50]. Therefore, the harsh operating conditions must be taken into account when designing suitable catalysts. Based on this, substantial research efforts have been devoted to investigating the low-precious-metal or precious-metal-free OER catalysts that are stable in acid media, such as perovskite, spinel, and the layer-structure-type family [23][51][52]. These kinds of catalysts also exhibit remarkable activity and are low-cost, easily synthesized, and environmentally benign [23].

2. Mechanisms for the OER in Acidic Media

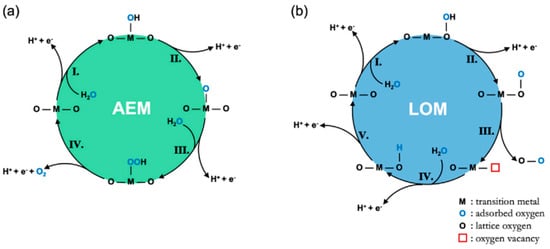

In the case of the OER in acid media, two possible mechanisms built on consecutive proton and electron transfers during the catalytic cycle, known as the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) and the lattice oxygen participation mechanism (LOM), have been widely accepted [24][26][53][54] (Figure 2). For the reaction path based on the AEM, a water molecule first adsorbs on a surface metal cation and decomposes into a proton (H+) to form HO*, which further dissociates the second proton to form O* in the second step. After that, HOO* is formed by the nucleophilic attack from another water molecule on the O*. Finally, oxygen is released, accompanied by the desorbed proton. Another four-electron transfer mechanism, known as the LOM, has been proposed based on a series of in-situ isotopic labeling experiments. In contrast to the AEM, lattice O participates in the formation of oxygen for the LOM. Firstly, one water molecule is adsorbed on a surface lattice O and dissociates the first proton to form HO*, which further dissociates the second proton to form O* in the second step. After that, oxygen is released via coupling absorbed O and a surface lattice O along with the presence of a surface oxygen vacancy. Finally, the surface lattice is restored as before via water adsorption and dissociation on the vacancy [24].

Figure 2. Diagrammatic sketch of (a) the AEM mechanism proposed by Rossmeisl et al. and (b) the LOER mechanism proposed by Rong et al. [24].

Although both of the mechanisms involve a four-electron transfer, there are still some differences between them [26]. The first one is that the AEM requires a higher reaction energy barrier (>320 mV) than the LOM theoretically [55]. In terms of active sites, the catalytic process predominantly involves a cationic redox (i.e., transition metal ions) in the AEM mechanism and an anion redox (i.e., lattice oxygen) in the LOM [56]. However, it varies according to actual conditions. Jones et al. demonstrated that both mechanisms exist in the OER, which can be detected by the charge storage behavior via the applied bias [57]. At a low bias, it mainly involves the charge storage of metal centers; at a high bias, it involves the storage of oxygen in IrOx. Moreover, strategies for increasing activity are different based on these two different mechanisms. On basis of the AEM, the active metal centers are always at a lower valence state, which can promote the nucleophilic attack of water molecules by increasing the covalence of metal and oxygen [43]. For example, Stoerzinger et al. simulated under-coordinated Ru atoms on a well-crystallized RuO2 surface with superior OER activity [58]. For the LOM, the metal center is often at a higher valence state, which is committed to promoting the generation of more electrophilic oxygen atoms and increasing the interaction between metal and oxygen [59]. Tarascon et al. studied the lattice oxygen behavior of La2LiIrO6. They believed that Ir was not the active site for the OER owing to the pH-dependent activity [60]. Despite the existing difference, some phenomena occurring in the process of an OER can still be explained by these theories. For example, excessive oxidation of metal sites for the AEM and lattice participation for the LOM generally lead to material instability [49]. Furthermore, the reason why the amorphous metal oxides exhibit better catalytic activity is that lattice oxygen can participate in the catalytic reaction easier than the well-crystallized ones [35].

It should be mentioned that, apart from increasing the site density, we can also optimize the composition to modify the intrinsic activity of the OER [33][61]. Recent work has pointed out the superiority of bi-metal oxides as some of the most advanced electrocatalysts toward the OER in acidic media, in terms of features including decreased Ru/Ir contents and enhanced OER activity and selectivity [23][62]. Incorporating suitable foreign metal atoms, such as Cr, Ni, Zn, and Cu atoms, can surprisingly improve the conductivity and alter the electronic structures of the original catalysts, thus enhancing their intrinsic activity [63][64]. It was reported that a low Ru content oxide material (Cr0.6Ru0.4O2) derived from a Cr-based metal–organic framework showed remarkable OER performance in acidic media [65]. The superior catalytic activity and stability can be assigned to the lower occupation at the Fermi level and the altered electronic structures by incorporating Cr. Regarding Ni-modified oxides, it is suggested that Ni serves as the sacrificial component, as its leaching generally leads to enhanced OER activity due to the formation of active OH-containing surface structures [66]. For instance, Ni leaching was observed during the OER process of bulk Ir–Ni mixed oxides with increased Ni contents (21 atomic%, 39 atomic%, and 89 atomic%), and the remaining Ni concentrations were similar in all systems, which turned out to be ~12 atomic% relative to the total amount of Ir and Ni in the oxides [67]. However, differences in their OER performance suggested variations in the resulting active sites caused by the sacrifice of Ni. This means that the OER performance of the catalysts is directly related to the transport kinetics of the electrons involved, and the reaction rate is determined also by the number of active sites. Therefore, it is important to prepare electrocatalysts with a sufficient reaction surface area in order to enable facile mass/electron transport and alter the interaction between metals and supports [68]. The most effective way is to minimize the size of catalyst nanoparticles to within several nanometers to make full use of each active site [36]. In addition, composition modification may also increase the number of catalytic sites. Doping Zn and Cu can confer moderate binding strength on oxygen intermediates, provide more defects or vacancies to enhance the intrinsic activity, and significantly increase the surface area to expose more active reaction sites [69]. However, difficult issues such as well-controlled monodispersity, stabilization of active sites, targeted synthesis, and macro-scale configuration for OER electrocatalysts still remain, especially in acidic media, both experimentally and theoretically [23][70].

3. Tailoring Strategies for Effective OER Electrocatalysts

An important frontier in OER electrocatalysis research is the development of the rational design of catalysts [71]. As discussed above, there are generally two strategies to improve catalytic performance: one is to increase the catalyst’s intrinsic activity, and the other is to increase the number of exposed active sites by structure/morphology optimization or by increased loading on a given electrode. Ideally, these two strategies are not mutually exclusive and can be addressed simultaneously, thereby leading to significantly improved activity.

3.1. Metal–Support Interaction

The interface between the metal center and the support will cause the re-arrangement of electrons originating from the support and anchored atoms [68][72]. The re-arranged electrons that have a significant impact on the catalytic performance will be confined in a space several atomic layers thick at the interface [73]. The magnitude and direction of the charge transfer are driven by differences in the Fermi level of the catalytic center and the support [50]. In addition, due to the special microenvironment at the interface, the interface sites will be in direct contact with the catalytic center, the carrier, and the reactants in order to promote the occurrence of synchronous reactions [37]. Additionally, the interface is conducive to the accumulation of excess charge during the charge transfer process, which will strongly promote the catalytic reactions at the interface [74].

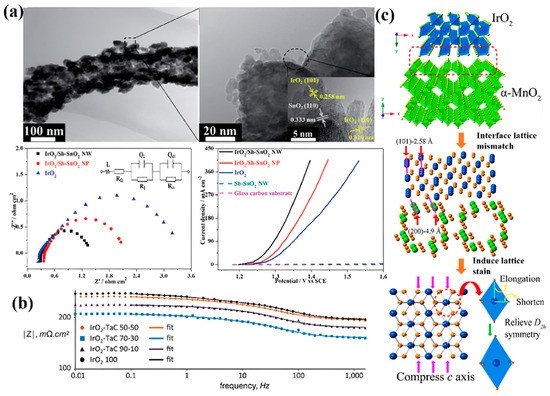

SnO2 and TiO2-based compounds are commonly used as supports due to their characteristic of stability [75][76]. In order to improve their low charge-transfer rate, extensive studies have modified them to improve the conductivity. For SnO2, Sb doping is often used to prepare Sb-SnO2 (ATO), and the conductivity of the material will be improved due to the increased electron carrier density caused by donor doping [77]. Moreover, the specific surface area and pore volume of SnO2 can be improved by destroying the long-range order of the original atomic arrangement so as to provide more anchor sites for IrO2 nanoparticles [76]. The interaction between IrO2 and the support, the cross-linking morphology of IrO2, and the porous structure can improve the OER performance of the catalyst. Wang’s group designed a kind of Sb-SnO2 nanowire carrier by an electrospinning method (Figure 3a) [37]. The conductivity can reach 0.83 S·cm−1. Compared with pure IrO2, the catalytic activity of supported IrO2/Sb-SnO2 exhibits significantly improved mass activity, benefiting from the porous structure and the high electronic conductivity of the Sb-SnO2 support [37].

Figure 3. (a) Low- and high-magnification transmission electron microscope (TEM) images, a Nyquist diagram, and the steady-state polarization curve of the IrO2/Sb-SnO2 catalyst [37]. (b) Bode plot from the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of TaC-supported IrO2 [78]. (c) Diagram of the process by which the α-MnO2 substrate induces the lattice strain of IrO2 [45].

In addition to metal oxides, metal carbides have also emerged as promising OER carriers because of their high conductivity and stability. A TaC-supported IrO2 catalyst sprayed by Polonsky et al. showed the lowest charge transfer resistance and the highest current density when the loading of IrO2 reached 70 wt%, which was significantly improved compared with unsupported IrO2 (Figure 3b) [78]. When TiC is employed as the support for Ir in PEMWE, Ir nanoparticles can be evenly distributed on the TiC surface, and the pore volume of Ir/TiC is twice that of pure Ir. All these advantages make the OER catalytic performance of Ir/TiC much better than that of pure Ir [79].

In general, the existence of a support has two major advantages. On one hand, catalyst particles can be well dispersed on the support surface and facilitate the construction of a three-phase interface consisting of the catalyst, the reactant water molecule, and the produced oxygen [80]. In fact, this effect has been widely used to explain the increased activity of supported catalysts. For example, Ir nanoparticles can be well dispersed onto the TiN carrier. The IrO2@Ir/TiN catalyst prepared by Xing’s group showed an enhanced catalytic performance [50]. The overpotential was only 265 mV at a current density of 10 mA·cm−2. Yang et al. synthesized iridium dioxide nanoparticle catalysts with α-MnO2 nanorods as supports by a simple two-step hydrothermal method. They found that iridium dioxide nanoparticles were subjected to compressive strain due to the lattice mismatch between IrO2 and α-MnO2 (Figure 3c) [45].

3.2. Electronic Structure

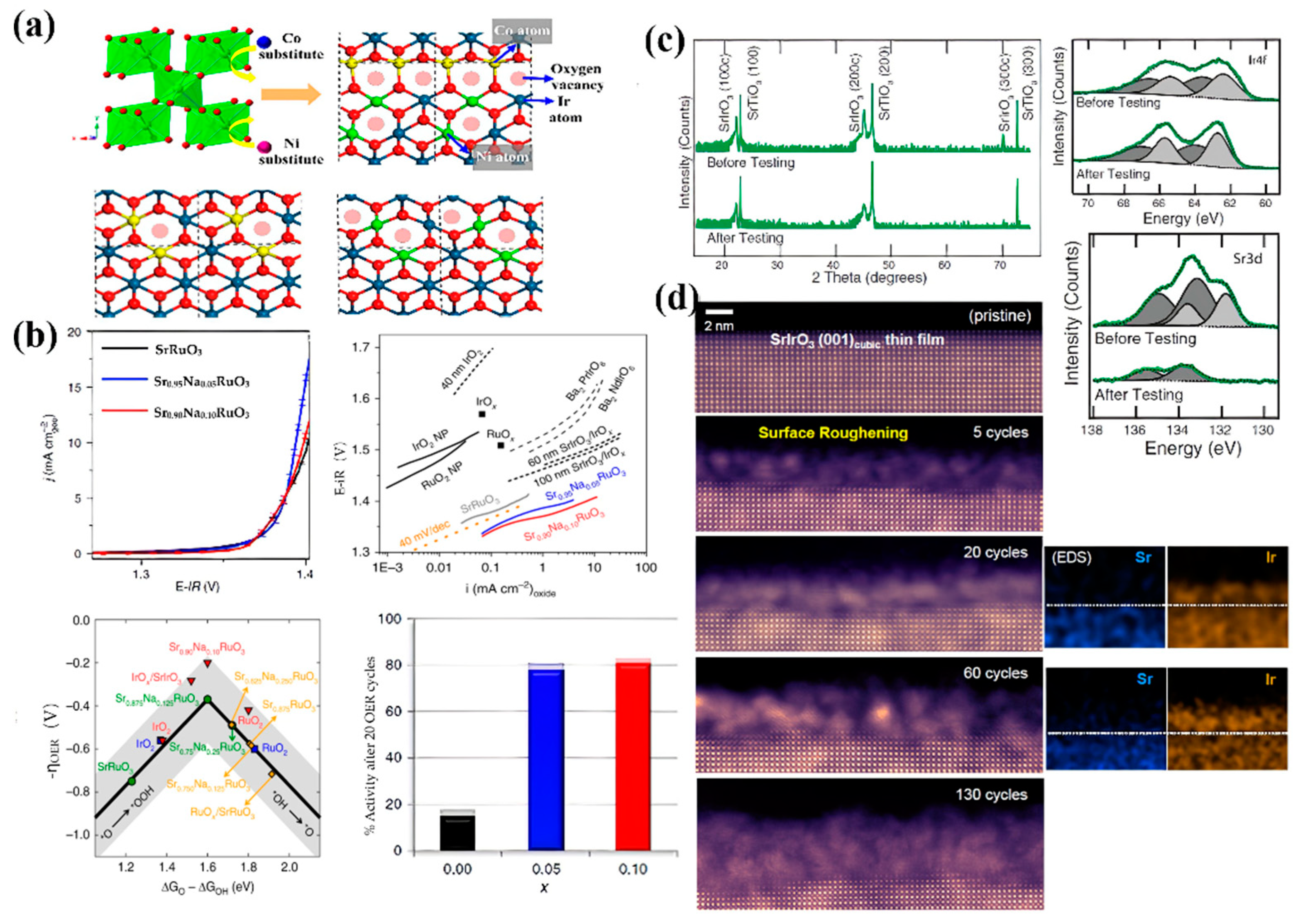

Incorporation of heteroatoms or groups will destroy the periodicity of the lattice, resulting in the modification of the local coordination environment and the electronic structure of active sites [35][81]. This change can effectively regulate the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates and improve the intrinsic activity of electrocatalysts. One of the effective strategies is to incorporate easily soluble non-noble metals, which suffer in-situ dissolution to form an amorphous structure, and increase the degree of coordination unsaturation of the metal in the active center during the oxygen evolution reaction [66]. Zaman et al. chose Ni and Co as the dopants to substitute 50% of the precious metal Ir. The Ni-Co co-doped IrO2 showed a low overpotential of 285 mV at a current density of 10 mA·cm−2 (Figure 4a) [82]. Besides Ir-based catalysts, researchers have also done a lot of work on Ru-based catalysts [83]. For example, SrRuO3 exhibited low OER activity in acid electrolytes due to rapid Sr leaching and Ru dissolution at high potential ranges in 0.1 M HClO4 [84]. Surprisingly, incorporating a small amount of Na+ into the lattice of SrRuO3 by substituting Sr2+ results in significantly enhanced OER performance, both in terms of activity and stability (Figure 4b) [85]. The doped sample exhibited 85% of activity retention after a stability test, which was assigned to the stabilization of Ru centers with a positive shift in dissolution potentials and less distorted RuO6 octahedra.

Figure 4. (a) Polyhedral model of IrO2 being doped with Ni and Co [82]. (b) Enhanced OER activity and durability of SrRuO3 by Na doping [85]. (c) XRD and XPS spectra of a SrIrO3 film before and after 30 h of OER testing [86]. (d) High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images of the surface structural evolution of a SrIrO3 film during the OER [87].

Preparation of a perovskite ABO3 structure (or A2BB′O6) and regulation of the valence band structure of B-site cations (usually Ir and Ru) by the atoms at A-site cations have commonly been used to improve the performance of the OER in recent years. Catalysts with this perovskite structure can greatly reduce the usage of noble metals. Pseudocubic SrIrO3 was the first AIrO3 single perovskite oxide reported for usage as an OER electrocatalyst in acid media [86]. It was found that the formation of IrOx by Sr leaching on the surface of SrIrO3 through surface reconstruction was responsible for the enhanced OER activity (Figure 4c). The active surface area increased significantly owing to the formation of IrOx groups on the surface of catalysts during cycling. Moreover, the intrinsic activity of Ir in the SrCo0.9Ir0.1O3-δ electrocatalyst was more than two orders of magnitude higher than that of IrO2 and approximately 10-fold higher as compared with the unmodified benchmark SrIrO3 [88]. The observed high activity was attributed to the surface reconstruction through Sr and Co leaching during the electrochemical cycling, which contains a large number of oxygen vacancies with corner-shared and under-coordinated IrOx octahedrons in the oxide crystal lattice. Furthermore, surface reconstruction of AIrO3 (A = Sr or Ba) perovskite oxides was visualized by atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (Figure 4d) [87]. Leaching of Sr or Ba happened by applying an anodic current, resulting in surface roughening and a structure change by the continuous formation of the mosaic-shaped, Sr-deficient IrOx on the surface. Moreover, the lattice strain induced by the substitution of smaller lanthanides or yttrium atoms can effectively decrease the adsorption energy toward oxygen-containing intermediates [51]. Although promising in terms of providing enhanced activity, such a surface reconstruction during the electrocatalysis process may be challenged by the uncertainty of the exact structure formed during reactions [86].

It should be mentioned that different kinds of crystal structures have a significant impact on the OER performance. It was proposed that monoclinic SrIrO3 underwent less surface reconstruction than the pseudocubic SrIrO3 owing to the better thermodynamic stability during OER tests in an acidic electrolyte [89]. Strong Ir–Ir metallic bonding and Ir–O covalent bonding in monoclinic SrIrO3 together induced its high structural and compositional stability. Only about 1% of the leached Sr was detected after 30 h in a chronopotentiometry test, which was much less than that (24%) from the pseudocubic SrIrO3. Additionally, Zou et al. put forward another way to decrease the cation leaching and surface reconstruction of pseudocubic SrIrO3 in acid media. They prepared pseudocubic, low-Ir-containing SrIrxTi1−xO3 perovskite oxides with 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.67. The inert Ti sites in pristine SrTiO3 were activated by Ir-substitution and showed remarkable OER activity with a reserved crystal structure of Ir-SrIrO3 during OER cycling [90].

For metal alloy/oxide-based electrocatalysts, the surface oxidation of metal atoms accompanied by de-alloying (surface dissolution of unstable metals) under acid OER conditions is considered to be a “surface engineering” strategy to design stable and efficient OER electrocatalysts. For example, Travis Jones and Peter Strasser found that electrochemical de-alloying and surface oxidation treatment of IrNi3.2 nanoparticle precursors can lead to the dissolution of Ni, and the formed Ni nanoparticles showed better catalytic performance than core–shell-structured IrNi@IrOx [56]. In order to investigate the relationship between the reconstructed structure and the enhanced OER performance, an operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) analysis was performed to characterize the local electronic properties under the OER process. The results show that iridium titania and d-band holes appear in the IrNiOx electrocatalyst when the potential increases from 0.4 to 1.5 VRHE. More importantly, due to the higher oxidation state of iridium, the iridium oxygen bond length in IrNiOx was significantly shortened. Based on this unique phenomenon, a structural model of the iridium oxygen ligand environment was proposed. The model shows that the hole-doped iridium ion sites around the electrophilic oxygen ligands form hole-doped IrOx (caused by Ni leaching) during the OER. Therefore, more electrophilic oxygen ligands are susceptible to the nucleophilic attack of water molecules or hydroxyl ligands, resulting in the formation of oxygen bonds and the reduction of the kinetic energy barrier, which ultimately greatly improves the reaction activity.

3.3. Coordination Environment

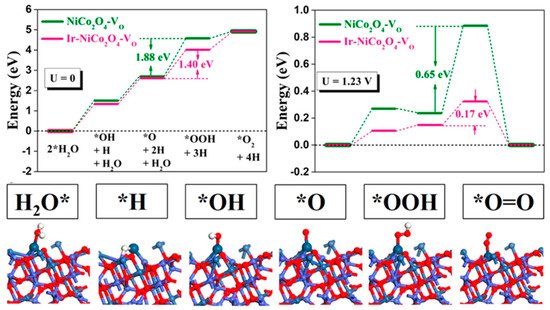

Although great efforts have been made to improve the efficiency of OER electrocatalysts, the majority of active sites inside their bulk phases remain inaccessible [23]. In order to maximize the utilization of each active site (approaching 100%) as well as shed light on the effect of the structure of active centers and ligating atoms on the OER activity, catalysts have thus been continuously downsized to the single-atom (SA) level. Single-atom catalysts (SACs) have emerged as a hot new branch of heterogeneous catalysts due to their excellent catalytic performance and financial benefits [28]. Owing to the high requirements for the dispersion, activity, and stability of the atoms, an appropriate support must be selected to optimize the physiochemical properties of the metal atoms anchored [80]. The unique coordination configuration of the dispersed metal atoms and coordinating atoms together create active sites for OER catalysts; therefore, the coordination−activity relationship has a strong impact on the catalytic performance [91]. In fact, targeted synthesis of precious metal single-atom-based OER electrocatalysts remains a bottleneck and has been pursued in the search for better OER catalysis, especially under acid conditions [28]. Generally, carbon supports often suffer severe corrosion problems under acid conditions and oxide supports are not always conductive, which brings about huge trouble for the design of single-atom catalysts [92]. In order to solve these problems, a series of Pt-Cu alloys with an atomically dispersed Ru1 decoration were studied by Yao et al. [93]. An ultralow overpotential of 170 mV at a current density of 10 mA·cm−2 was reached by Ru1-Pt3Cu in acid media, together with a ten times longer lifetime than a commercial RuO2 catalyst. Density functional theory calculations suggested that the electronic structure of single Ru sites at the corner or step sites of the Pt-rich shell was modulated by the compressive strain in the Pt skin shell, contributing to the optimized binding of oxygen species and improved resistance to over-oxidation and dissolution. Yin et al. demonstrated that surface-exposed Ir single atom couplings with oxygen vacancies anchored in ultrathin NiCo2O4 porous nanosheets exhibited remarkable OER activity and stability in acid media, with an overpotential of only 240 mV at a current density of 10 mA·cm−2 and a long-term durability of 70 h [28]. Based on density functional theory calculations, high electronic exchange and transfer activities of the surface contributed by Ir atoms anchored at Co sites near oxygen vacancies were determined to be responsible for the prominent OER performance (Figure 5). The synergetic mutual activation between Ir and Co reached the desired H2O activation level and stabilized *O to boost OER performance.

Figure 5. OER pathway under acidic conditions and local structural configurations of intermediates on the Ir−NiCo2O4−VO [28].

3.4. Morphology

The interface between the catalyst and the electrolyte plays an important role in water electrocatalysis [94]. As a very important aspect of a surface structure, morphology has attracted much attention in recent years [23][95]. To date, many methods to control the morphology have been proposed [23][61].

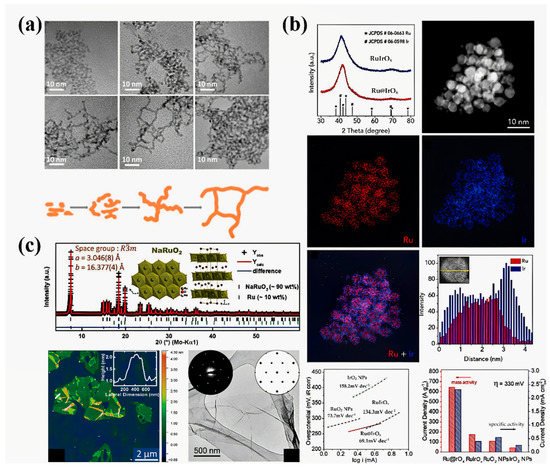

The morphology of the catalyst can be modified by adopting a suitable preparation strategy, such as the template method, the solvothermal method, or the seed crystal method [96][97]. A nano-porous or ultra-thin structure can increase the number of exposed active sites. Luo et al. prepared a new kind of Ir nanowire with a diameter of 1.7 nm by a wet chemical method (Figure 6a) [61]. Due to the high aspect ratio and large specific surface area, the OER activity increased greatly. The overpotential at 10 mA·cm−2 in 0.5 M HClO4 is only 270 mV, which is significantly higher than that of Ir nanoparticles.

Figure 6. (a) TEM images and a schematic illustration of Ir nanowire intermediates obtained at different reaction times from 5 min to 20 h [61]. (b) Fine-structure characterization of a Ru@IrOx catalyst and investigation of its OER electrocatalytic activity [98]. (c) Fine-structure characterizations of ultra-thin NaRuO2 nanosheets including the crystal structure, an atomic force microscopy (AFM) image, a TEM image, and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns [99].

In fact, the electronic structure of catalytic centers can be modified by defects as well as the morphology. For example, Qiao et al. prepared a core–shell Ru@IrOx icosahedral nanocrystal structure by the sequential polyol method, in which a highly distorted lattice can be observed (Figure 6b) [98]. Due to the interaction between the ruthenium core and the iridium shell, ruthenium is subjected to compressive strain, which was confirmed by the decrease in the distance between ruthenium and ruthenium atoms observed by EXAFS. This strain may lead to a shift in the d-band center, which can regulate the binding energy of oxygen intermediates and the activity of the OER. In addition to the lattice strain, morphology control can also lead to changes in the chemical composition, which directly affects the electronic structure. An example is the ultra-thin ruthenium oxide nanosheets prepared by Lotsch’s group (Figure 6c) [99]. Owing to the acid treatment in the stripping process, the actual composition of ruthenium oxide is HxRuO2, in which the valence of ruthenium is +3/+4. Therefore, ruthenium oxide nanoparticles exhibit enhanced OER activity and stability.

References

- Cook, T.R.; Dogutan, D.K.; Reece, S.Y.; Surendranath, Y.; Teets, T.S.; Nocera, D.G. Solar Energy Supply and Storage for the Legacy and Nonlegacy Worlds. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6474–6502.

- Suen, N.T.; Hung, S.F.; Quan, Q.; Zhang, N.; Xu, Y.J.; Chen, H.M. Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: Recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 337.

- Benson, E.E.; Kubiak, C.P.; Sathrum, A.J.; Smieja, J.M. Electrocatalytic and homogeneous approaches to conversion of CO2 to liquid fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 89–99.

- Turner, J.A. Sustainable hydrogen production. Science 2004, 305, 972–974.

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303.

- Reier, T.; Nong, H.N.; Teschner, D.; Schlögl, R.; Strasser, P. Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Acidic Environments—Reaction Mechanisms and Catalysts. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601275.

- Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yin, M.; Wang, J.; Gao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, T.; Wang, Z.L. Gravity triboelectric nanogenerator for the steady harvesting of natural wind energy. Nano Energy 2021, 82, 105740.

- Surya Prakash, V.; Manoj Kumar, G.; Gouthem, S.E.; Srithar, A. Solar powered seed sowing machine. Mater. Today Proc. 2021.

- Wei, C.; Rao, R.R.; Peng, J.; Huang, B.; Stephens, I.E.L.; Risch, M.; Xu, Z.J.; Shao-Horn, Y. Recommended Practices and Benchmark Activity for Hydrogen and Oxygen Electrocatalysis in Water Splitting and Fuel Cells. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1806296.

- King, L.A.; Hubert, M.A.; Capuano, C.; Manco, J.; Danilovic, N.; Valle, E.; Hellstern, T.R.; Ayers, K.; Jaramillo, T.F. A non-precious metal hydrogen catalyst in a commercial polymer electrolyte membrane electrolyser. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1071–1074.

- Kibsgaard, J.; Chorkendorff, I. Considerations for the scaling-up of water splitting catalysts. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 430–433.

- You, B.; Sun, Y. Innovative Strategies for Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1571–1580.

- Baeumer, C.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Liang, A.Y.-L.; Jin, L.; Martins, H.P.; Duchoň, T.; Glöß, M.; Gericke, S.M.; Wohlgemuth, M.A.; et al. Tuning electrochemically driven surface transformation in atomically flat LaNiO3 thin films for enhanced water electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 674–682.

- Wu, C.W.; Zhang, W.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.X.; Ma, G.J. A systematic review for structure optimization and clamping load design of large proton exchange membrane fuel cell stack. J. Power Sources 2020, 476, 228724.

- Choi, C.; Ashby, D.S.; Butts, D.M.; DeBlock, R.H.; Wei, Q.; Lau, J.; Dunn, B. Achieving high energy density and high power density with pseudocapacitive materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 5–19.

- Montoya, J.H.; Seitz, L.C.; Chakthranont, P.; Vojvodic, A.; Jaramillo, T.F.; Norskov, J.K. Materials for solar fuels and chemicals. Nat. Mater. 2016, 16, 70–81.

- Fan, M.; Liang, X.; Chen, H.; Zou, X. Low-iridium electrocatalysts for acidic oxygen evolution. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 15568–15573.

- Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Du, Y.; Xi, S.; Sun, Y.; Sherburne, M.; Ager, J.W.; Fisher, A.C.; Xu, Z.J. Exceptionally active iridium evolved from a pseudo-cubic perovskite for oxygen evolution in acid. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 572.

- Bhattacharyya, K.; Poidevin, C.; Auer, A.A. Structure and Reactivity of IrOx Nanoparticles for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Electrocatalysis: An Electronic Structure Theory Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 4379–4390.

- Huang, Z.-F.; Song, J.; Dou, S.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Strategies to Break the Scaling Relation toward Enhanced Oxygen Electrocatalysis. Matter 2019, 1, 1494–1518.

- Tao, H.B.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Pei, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.G.; Liu, B. A General Method to Probe Oxygen Evolution Intermediates at Operating Conditions. Joule 2019, 3, 1498–1509.

- Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Yu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W. Water Splitting: From Electrode to Green Energy System. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 131.

- Chen, H.; Shi, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, L.; Asefa, T.; Zou, X. Optimization of Active Sites via Crystal Phase, Composition and Morphology for Efficient Low-Iridium Oxygen Evolution Catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 132, 19822–19826.

- Gu, X.-K.; Camayang, J.C.A.; Samira, S.; Nikolla, E. Oxygen evolution electrocatalysis using mixed metal oxides under acidic conditions: Challenges and opportunities. J. Catal. 2020, 388, 130–140.

- Siwal, S.S.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q. Recent progress of precious-metal-free electrocatalysts for efficient water oxidation in acidic media. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 51, 113–133.

- Song, J.; Wei, C.; Huang, Z.F.; Liu, C.; Zeng, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.J. A review on fundamentals for designing oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2196–2214.

- Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Dang, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L.; Jin, S. Amorphous Cobalt-Iron Hydroxide Nanosheet Electrocatalyst for Efficient Electrochemical and Photo-Electrochemical Oxygen Evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1603904.

- Yin, J.; Jin, J.; Lu, M.; Huang, B.L.; Zhang, H.; Peng, Y.; Xi, P.X.; Yan, C.H. Iridium Single Atoms Coupling with Oxygen Vacancies Boosts Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Acid Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18378–18386.

- Danilovic, N.; Subbaraman, R.; Chang, K.C.; Chang, S.H.; Kang, Y.J.; Snyder, J.; Paulikas, A.P.; Strmcnik, D.; Kim, Y.T.; Myers, D.; et al. Activity-Stability Trends for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction on Monometallic Oxides in Acidic Environments. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2474–2478.

- Audichon, T.; Napporn, T.W.; Canaff, C.; Morais, C.; Comminges, C.; Kokoh, K.B. IrO2 Coated on RuO2 as Efficient and Stable Electroactive Nanocatalysts for Electrochemical Water Splitting. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 2562–2573.

- Li, G.; Li, S.; Ge, J.; Liu, C.; Xing, W. Discontinuously covered IrO2–RuO2@Ru electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction: How high activity and long-term durability can be simultaneously realized in the synergistic and hybrid nano-structure. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 17221–17229.

- Cao, L.; Luo, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Shen, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; et al. Dynamic oxygen adsorption on single-atomic Ruthenium catalyst with high performance for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4849.

- Chandra, D.; Abe, N.; Takama, D.; Saito, K.; Yui, T.; Yagi, M. Open pore architecture of an ordered mesoporous IrO2 thin film for highly efficient electrocatalytic water oxidation. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 795–799.

- Chen, J.; Cui, P.; Zhao, G.; Rui, K.; Lao, M.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Pan, H.; Dou, S.X.; et al. Low-Coordinate Iridium Oxide Confined on Graphitic Carbon Nitride for Highly Efficient Oxygen Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12540–12544.

- Gao, J.; Xu, C.Q.; Hung, S.F.; Liu, W.; Cai, W.; Zeng, Z.; Jia, C.; Chen, H.M.; Xiao, H.; Li, J.; et al. Breaking Long-Range Order in Iridium Oxide by Alkali Ion for Efficient Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3014–3023.

- Han, X.B.; Tang, X.Y.; Lin, Y.; Gracia-Espino, E.; Liu, S.G.; Liang, H.W.; Hu, G.Z.; Zhao, X.J.; Liao, H.G.; Tan, Y.Z.; et al. Ultrasmall Abundant Metal-Based Clusters as Oxygen-Evolving Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 232–239.

- Liu, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. An oxygen evolution catalyst on an antimony doped tin oxide nanowire structured support for proton exchange membrane liquid water electrolysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 20791–20800.

- Liang, X.; Shi, L.; Cao, R.; Wan, G.; Yan, W.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zou, X. Perovskite-Type Solid Solution Nano-Electrocatalysts Enable Simultaneously Enhanced Activity and Stability for Oxygen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2001430.

- Craig, M.J.; Coulter, G.; Dolan, E.; Soriano-Lopez, J.; Mates-Torres, E.; Schmitt, W.; Garcia-Melchor, M. Universal scaling relations for the rational design of molecular water oxidation catalysts with near-zero overpotential. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4993.

- Alia, S.M.; Shulda, S.; Ngo, C.; Pylypenko, S.; Pivovar, B.S. Iridium-Based Nanowires as Highly Active, Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2111–2120.

- Wu, G.; Zheng, X.; Cui, P.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Qu, Y.; Chen, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, H.; Han, X.; et al. A general synthesis approach for amorphous noble metal nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4855.

- Yee, D.W.; Lifson, M.L.; Edwards, B.W.; Greer, J.R. Additive Manufacturing of 3D-Architected Multifunctional Metal Oxides. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901345.

- Cheng, J.; Yang, J.; Kitano, S.; Juhasz, G.; Higashi, M.; Sadakiyo, M.; Kato, K.; Yoshioka, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Yamauchi, M.; et al. Impact of Ir-Valence Control and Surface Nanostructure on Oxygen Evolution Reaction over a Highly Efficient Ir–TiO2 Nanorod Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6974–6986.

- Shan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, B.; Davey, K.; Qiao, S.-Z. Regulating Electrocatalysts via Surface and Interface Engineering for Acidic Water Electrooxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2719–2730.

- Sun, W.; Zhou, Z.H.; Zaman, W.Q.; Cao, L.M.; Yang, J. Rational Manipulation of IrO2 Lattice Strain on alpha-MnO2 Nanorods as a Highly Efficient Water-Splitting Catalyst. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41855–41862.

- Moon, S.; Cho, Y.B.; Yu, A.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, C.; Lee, Y. Single-Step Electrospun Ir/IrO2 Nanofibrous Structures Decorated with Au Nanoparticles for Highly Catalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 1979–1987.

- Massue, C.; Pfeifer, V.; Huang, X.; Noack, J.; Tarasov, A.; Cap, S.; Schlogl, R. High-Performance Supported Iridium Oxohydroxide Water Oxidation Electrocatalysts. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1943–1957.

- Hornberger, E.; Bergmann, A.; Schmies, H.; Kühl, S.; Wang, G.; Drnec, J.; Sandbeck, D.J.S.; Ramani, V.; Cherevko, S.; Mayrhofer, K.J.J.; et al. In Situ Stability Studies of Platinum Nanoparticles Supported on Ruthenium−Titanium Mixed Oxide (RTO) for Fuel Cell Cathodes. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9675–9683.

- Geiger, S.; Kasian, O.; Ledendecker, M.; Pizzutilo, E.; Mingers, A.M.; Fu, W.T.; Diaz-Morales, O.; Li, Z.; Oellers, T.; Fruchter, L.; et al. The stability number as a metric for electrocatalyst stability benchmarking. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 508–515.

- Li, G.; Li, K.; Yang, L.; Chang, J.; Ma, R.; Wu, Z.; Ge, J.; Liu, C.; Xing, W. Boosted Performance of Ir Species by Employing TiN as the Support toward Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 38117–38124.

- Diaz-Morales, O.; Raaijman, S.; Kortlever, R.; Kooyman, P.J.; Wezendonk, T.; Gascon, J.; Fu, W.T.; Koper, M.T.M. Iridium-based double perovskites for efficient water oxidation in acid media. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 6.

- Barforoush, J.M.; Seuferling, T.E.; Jantz, D.T.; Song, K.R.; Leonard, K.C. Insights into the Active Electrocatalytic Areas of Layered Double Hydroxide and Amorphous Nickel-Iron Oxide Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysts. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 1415–1423.

- Shi, Q.; Zhu, C.; Du, D.; Lin, Y. Robust noble metal-based electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 3181–3192.

- Lv, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, K.; Wang, C.; Xiong, Y. 2D Layered Double Hydroxides for Oxygen Evolution Reaction: From Fundamental Design to Application. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803358.

- Grimaud, A.; Diaz-Morales, O.; Han, B.; Hong, W.T.; Lee, Y.L.; Giordano, L.; Stoerzinger, K.A.; Koper, M.T.M.; Shao-Horn, Y. Activating lattice oxygen redox reactions in metal oxides to catalyse oxygen evolution. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 457–465.

- Nong, H.N.; Tran, H.P.; Spori, C.; Klingenhof, M.; Frevel, L.; Jones, T.E.; Cottre, T.; Kaiser, B.; Jaegermann, W.; Schlogl, R.; et al. The Role of Surface Hydroxylation, Lattice Vacancies and Bond Covalency in the Electrochemical Oxidation of Water (OER) on Ni-Depleted Iridium Oxide Catalysts. Z. Fur Phys. Chem.-Int. J. Res. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 234, 787–812.

- Nong, H.N.; Falling, L.J.; Bergmann, A.; Klingenhof, M.; Tran, H.P.; Spori, C.; Mom, R.; Timoshenko, J.; Zichittella, G.; Knop-Gericke, A.; et al. Key role of chemistry versus bias in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Nature 2020, 587, 408–413.

- Stoerzinger, K.A.; Diaz-Morales, O.; Kolb, M.; Rao, R.R.; Frydendal, R.; Qiao, L.; Wang, X.R.; Halck, N.B.; Rossmeisl, J.; Hansen, H.A.; et al. Orientation-Dependent Oxygen Evolution on RuO2 without Lattice Exchange. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 876–881.

- Zhang, N.; Feng, X.; Rao, D.; Deng, X.; Cai, L.; Qiu, B.; Long, R.; Xiong, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chai, Y. Lattice oxygen activation enabled by high-valence metal sites for enhanced water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4066.

- Grimaud, A.; Demortière, A.; Saubanère, M.; Dachraoui, W.; Duchamp, M.; Doublet, M.-L.; Tarascon, J.-M. Activation of surface oxygen sites on an iridium-based model catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Energy 2016, 2, 16189.

- Fu, L.; Yang, F.; Cheng, G.; Luo, W. Ultrathin Ir nanowires as high-performance electrocatalysts for efficient water splitting in acidic media. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 1892–1897.

- Jin, Z.; Lv, J.; Jia, H.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Lin, X.; Xie, G.; Liu, X.; Sun, S.; et al. Nanoporous Al-Ni-Co-Ir-Mo High-Entropy Alloy for Record-High Water Splitting Activity in Acidic Environments. Small 2019, 15, e1904180.

- Nong, H.N.; Reier, T.; Oh, H.-S.; Gliech, M.; Paciok, P.; Vu, T.H.T.; Teschner, D.; Heggen, M.; Petkov, V.; Schlögl, R.; et al. A unique oxygen ligand environment facilitates water oxidation in hole-doped IrNiOx core–shell electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 841–851.

- Strickler, A.L.; Flores, R.A.; King, L.A.; Norskov, J.K.; Bajdich, M.; Jaramillo, T.F. Systematic Investigation of Iridium-Based Bimetallic Thin Film Catalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Acidic Media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 34059–34066.

- Lin, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Jiang, Z.; Deibert, B.J.; Ge, R.; Chen, L. Chromium-ruthenium oxide solid solution electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 162.

- Pi, Y.C.; Shao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Huang, X.Q. Dynamic Structure Evolution of Composition Segregated Iridium-Nickel Rhombic Dodecahedra toward Efficient Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 7371–7379.

- Reier, T.; Pawolek, Z.; Cherevko, S.; Bruns, M.; Jones, T.; Teschner, D.; Selve, S.; Bergmann, A.; Nong, H.N.; Schlogl, R.; et al. Molecular Insight in Structure and Activity of Highly Efficient, Low-Ir Ir-Ni Oxide Catalysts for Electrochemical Water Splitting (OER). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13031–13040.

- Bele, M.; Stojanovski, K.; Jovanovič, P.; Moriau, L.; Koderman Podboršek, G.; Moškon, J.; Umek, P.; Sluban, M.; Dražič, G.; Hodnik, N.; et al. Towards Stable and Conductive Titanium Oxynitride High-Surface-Area Support for Iridium Nanoparticles as Oxygen Evolution Reaction Electrocatalyst. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 5038–5044.

- Ge, R.; Li, L.; Su, J.; Lin, Y.; Tian, Z.; Chen, L. Ultrafine Defective RuO2 Electrocatayst Integrated on Carbon Cloth for Robust Water Oxidation in Acidic Media. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901313.

- Kwon, J.; Han, H.; Choi, S.; Park, K.; Jo, S.; Paik, U.; Song, T. Current Status of Self-Supported Catalysts for Robust and Efficient Water Splitting for Commercial Electrolyzer. ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 5898–5912.

- Zhang, B.; Zheng, X.L.; Voznyy, O.; Comin, R.; Bajdich, M.; Garcia-Melchor, M.; Han, L.L.; Xu, J.X.; Liu, M.; Zheng, L.R.; et al. Homogeneously dispersed multimetal oxygen-evolving catalysts. Science 2016, 352, 333–337.

- Dong, C.; Li, Y.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.-G.; Xiao, D.; Ma, D. Supported Metal Clusters: Fabrication and Application in Heterogeneous Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11011–11045.

- Li, X.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, B. Supported Noble-Metal Single Atoms for Heterogeneous Catalysis. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1902031.

- Lou, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, C.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, Y. Metal-support interaction for heterogeneous catalysis: From nanoparticles to single atoms. Mater. Today Nano 2020, 12, 100093.

- Chen, P.; Lu, J.; Xie, G.; Zhu, L.; Luo, M. Characterizations of Ir/TiO2 catalysts with different Ir contents for selective hydrogenation of crotonaldehyde. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2012, 106, 419–434.

- Xu, J.; Liu, G.; Li, J.; Wang, X. The electrocatalytic properties of an IrO2/SnO2 catalyst using SnO2 as a support and an assisting reagent for the oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 59, 105–112.

- Wu, X.; Scott, K. RuO2 supported on Sb-doped SnO2 nanoparticles for polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolysers. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 5806–5810.

- Polonsky, J.; Mazur, P.; Paidar, M.; Christensen, E.; Bouzek, K. Performance of a PEM water electrolyser using a TaC-supported iridium oxide electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 3072–3078.

- Ma, L.; Sui, S.; Zhai, Y. Preparation and characterization of Ir/TiC catalyst for oxygen evolution. J. Power Sources 2008, 177, 470–477.

- Jiang, B.; Wang, T.; Cheng, Y.; Liao, F.; Wu, K.; Shao, M. Ir/g-C3N4/Nitrogen-Doped Graphene Nanocomposites as Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting in Acidic Electrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 39161–39167.

- Yang, C.; Rousse, G.; Louise Svane, K.; Pearce, P.E.; Abakumov, A.M.; Deschamps, M.; Cibin, G.; Chadwick, A.V.; Dalla Corte, D.A.; Anton Hansen, H.; et al. Cation insertion to break the activity/stability relationship for highly active oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1378.

- Zaman, W.Q.; Wang, Z.Q.; Sun, W.; Zhou, Z.H.; Tariq, M.; Cao, L.M.; Gong, X.Q.; Yang, J. Ni-Co Codoping Breaks the Limitation of Single-Metal-Doped IrO2 with Higher Oxygen Evolution Reaction Performance and Less Iridium. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2786–2793.

- Kim, J.; Shih, P.C.; Tsao, K.C.; Pan, Y.T.; Yin, X.; Sun, C.J.; Yang, H. High-Performance Pyrochlore-Type Yttrium Ruthenate Electrocatalyst for Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Acidic Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12076–12083.

- Kim, B.J.; Abbott, D.F.; Cheng, X.; Fabbri, E.; Nachtegaal, M.; Bozza, F.; Castelli, I.E.; Lebedev, D.; Schaublin, R.; Coperet, C.; et al. Unraveling Thermodynamics, Stability, and Oxygen Evolution Activity of Strontium Ruthenium Perovskite Oxide. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3245–3256.

- Retuerto, M.; Pascual, L.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Ferrer, P.; Gianolio, D.; Pereira, A.G.; Garcia, A.; Torrero, J.; Fernandez-Diaz, M.T.; Bencok, P.; et al. Na-doped ruthenium perovskite electrocatalysts with improved oxygen evolution activity and durability in acidic media. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 9.

- Seitz, L.C.; Dickens, C.F.; Nishio, K.; Hikita, Y.; Montoya, J.; Doyle, A.; Kirk, C.; Vojvodic, A.; Hwang, H.Y.; Norskov, J.K.; et al. A highly active and stable IrOx/SrIrO3 catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Science 2016, 353, 1011–1014.

- Song, C.W.; Suh, H.; Bak, J.; Bae, H.B.; Chung, S.Y. Dissolution-Induced Surface Roughening and Oxygen Evolution Electrocatalysis of Alkaline-Earth Iridates in Acid. Chem 2019, 5, 3243–3259.

- Zhu, J.; Chen, Z.; Xie, M.; Lyu, Z.; Chi, M.; Mavrikakis, M.; Jin, W.; Xia, Y. Iridium-Based Cubic Nanocages with 1.1-nm-Thick Walls: A Highly Efficient and Durable Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation in an Acidic Medium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7244–7248.

- Yang, L.; Yu, G.T.; Ai, X.; Yan, W.S.; Duan, H.L.; Chen, W.; Li, X.T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, C.H.; Huang, X.R.; et al. Efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis in acid by a perovskite with face-sharing IrO6 octahedral dimers. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 9.

- Liang, X.; Shi, L.; Liu, Y.P.; Chen, H.; Si, R.; Yan, W.S.; Zhang, Q.; Li, G.D.; Yang, L.; Zou, X.X. Activating Inert, Nonprecious Perovskites with Iridium Dopants for Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction under Acidic Conditions. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 7631–7635.

- Kaiser, S.K.; Chen, Z.; Faust Akl, D.; Mitchell, S.; Perez-Ramirez, J. Single-Atom Catalysts across the Periodic Table. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11703–11809.

- Tamaki, T.; Wang, H.; Oka, N.; Honma, I.; Yoon, S.-H.; Yamaguchi, T. Correlation between the carbon structures and their tolerance to carbon corrosion as catalyst supports for polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2018, 43, 6406–6412.

- Yao, Y.C.; Hu, S.L.; Chen, W.X.; Huang, Z.Q.; Wei, W.C.; Yao, T.; Liu, R.R.; Zang, K.T.; Wang, X.Q.; Wu, G.; et al. Engineering the electronic structure of single atom Ru sites via compressive strain boosts acidic water oxidation electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2019, 2, 304–313.

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, C.; Xing, W.; Ge, J. Reactant friendly hydrogen evolution interface based on di-anionic MoS2 surface. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1116.

- Lu, Z.-X.; Shi, Y.; Gupta, P.; Min, X.-P.; Tan, H.-Y.; Wang, Z.-D.; Guo, C.-Q.; Zou, Z.-Q.; Yang, H.; Mukerjee, S.; et al. Electrochemical fabrication of IrOx nanoarrays with tunable length and morphology for solid polymer electrolyte water electrolysis. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 348, 136302.

- Ortel, E.; Reier, T.; Strasser, P.; Kraehnert, R. Mesoporous IrO2 Films Templated by PEO-PB-PEO Block-Copolymers: Self-Assembly, Crystallization Behavior, and Electrocatalytic Performance. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 3201–3209.

- Li, G.; Li, S.; Xiao, M.; Ge, J.; Liu, C.; Xing, W. Nanoporous IrO2 catalyst with enhanced activity and durability for water oxidation owing to its micro/mesoporous structure. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 9291–9298.

- Shan, J.Q.; Guo, C.X.; Zhu, Y.H.; Chen, S.M.; Song, L.; Jaroniec, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qiao, S.Z. Charge-Redistribution-Enhanced Nanocrystalline x Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Evolution in Acidic Media. Chem 2019, 5, 445–459.

- Laha, S.; Lee, Y.; Podjaski, F.; Weber, D.; Duppel, V.; Schoop, L.M.; Pielnhofer, F.; Scheurer, C.; Muller, K.; Starke, U.; et al. Ruthenium Oxide Nanosheets for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Catalysis in Acidic Medium. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 8.