| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chengshang Zhou | + 4503 word(s) | 4503 | 2021-05-26 05:17:08 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4503 | 2021-05-31 10:12:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

Magnesium-based hydrides are considered as promising candidates for solid-state hydrogen storage and thermal energy storage, due to their high hydrogen capacity, reversibility, and elemental abundance of Mg. To improve the sluggish kinetics of MgH2, catalytic doping using Ti-based catalysts is regarded as an effective approach to enhance Mg-based materials.

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of the Mg-H2 System

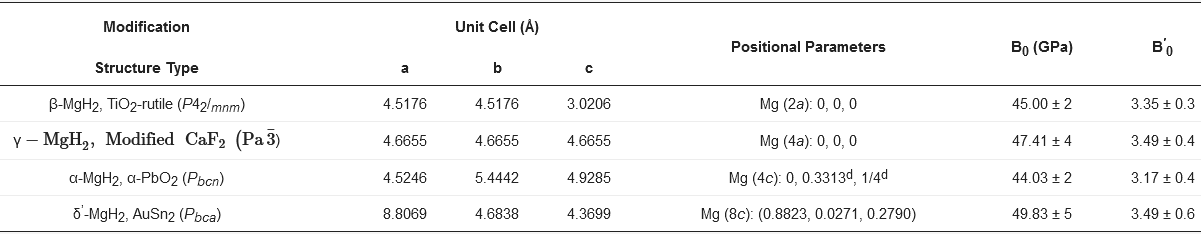

2.1. Crystal Structure

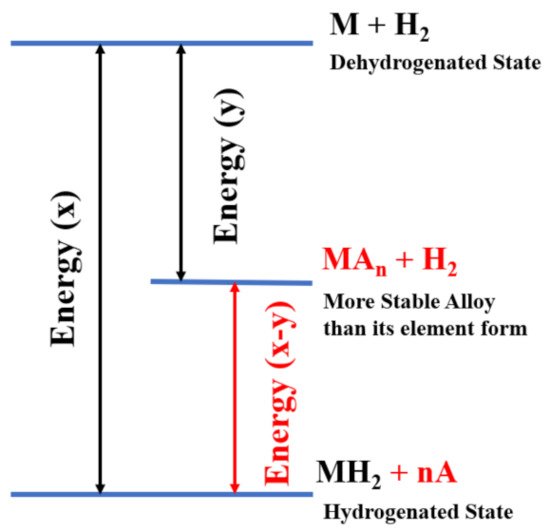

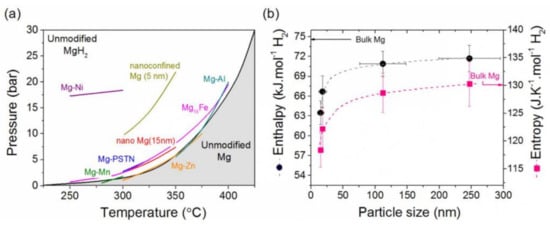

2.2. Thermodynamics of the Mg-H2 System

|

Thermodynamic Parameters |

Values |

|---|---|

|

Formation enthalpy, kJ/(mol·H2) |

−74.5 |

|

Formation entropy, J/(mol·H2·K) |

−135 |

|

Hydrogen Storage Capacity (Theoretical) |

|

|

Gravimetric capacity, wt% |

7.6 |

|

Volumetric capacity, g/(L·H2) |

110 |

|

Thermal Energy Storage Capacity (Theoretical) |

|

|

Gravimetric capacity, kJ/kg |

2204 |

|

Volumetric capacity, kJ/dm3 |

1763 |

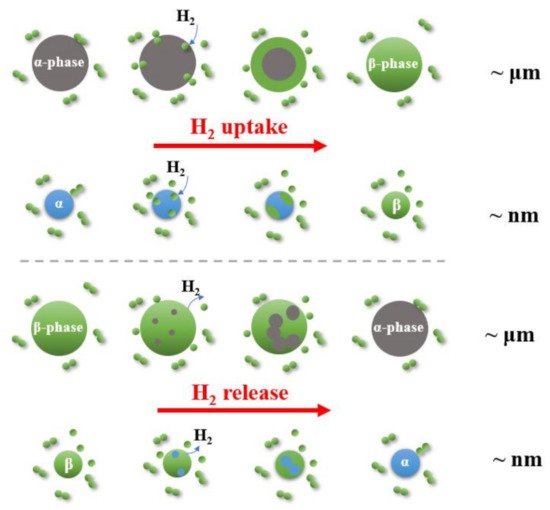

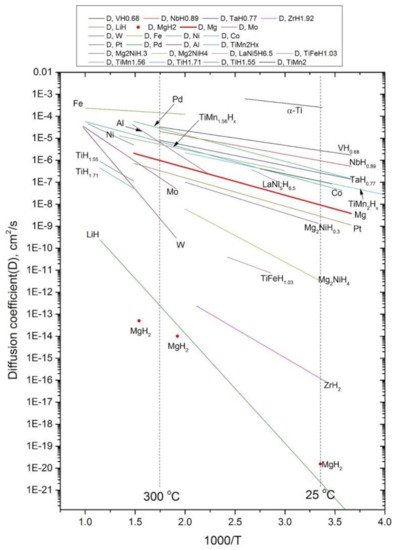

2.3. Kinetics

|

Metal |

Dissociation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|

|

Pure Mg |

0.87, 0.40, 0.50, 1.15, 1.05, 0.95, 1.00 |

|

Ti-doped Mg |

Null, negligible |

|

Ni-doped Mg |

0.06 |

|

V-doped Mg |

Null |

|

Cu-doped Mg |

0.56 |

|

Pd-doped Mg |

0.39 |

|

Fe-doped Mg |

0.03 |

|

Ag-doped Mg |

1.18 |

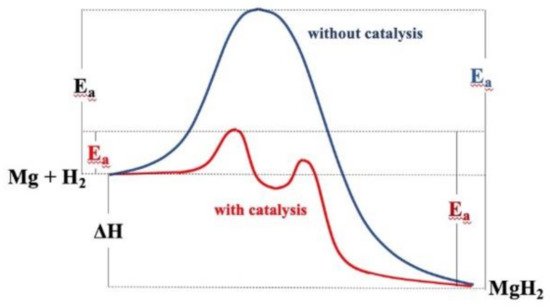

3. Catalytic Effects

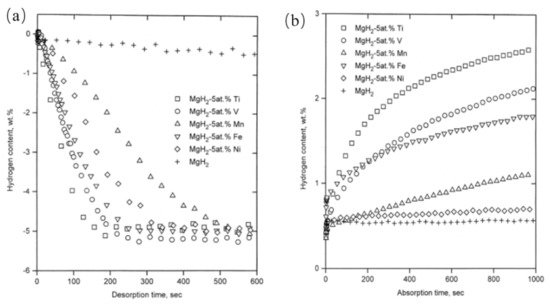

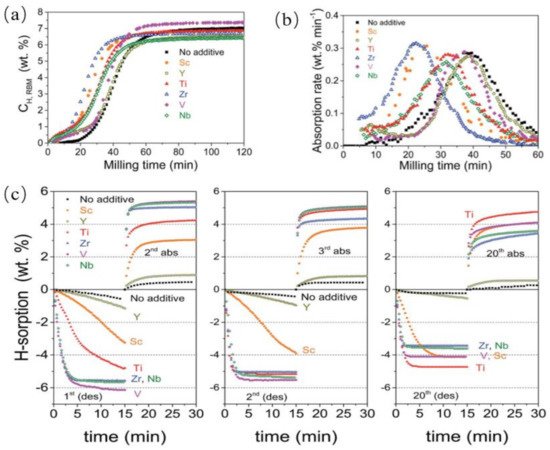

3.1. Transition Metals Catalysts

|

Materials |

Synthetic Methods |

Hydrogen Storage Properties |

Reference |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Desorption Kinetics |

Eades (kJ/mol) |

Absorption Kinetics |

Eaabs (kJ/mol) |

|||

|

Titanium/Titanium Hydrides |

||||||

|

Mg-2%Ti |

Inert gas condensation |

Des: 4.50%/320 °C/0.2 bar/25 min |

Abs: 4.80%/320 °C/8 bar/21 min |

[53] |

||

|

MgH2 + 2 at% Ti |

Ball milling (argon) |

Des: 6.32 wt%/623 K/35 kPa/0.5 h |

Abs: 6.32 wt%/623 K/2000 kPa/4 min |

[54] |

||

|

Cold rolling (5 times, air) |

Des: 6.00 wt%/623 K/35 kPa/0.5 h |

Abs: 5.70 wt%/623 K/2000 kPa/4 min |

||||

|

MgH2-4 mol% Ti |

Ball milling |

Des: 1.10%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

Abs: 6.40%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

[55] |

||

|

MgH2-5 at% Ti |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 235.6 °C |

70.11 |

[56] |

||

|

MgH2-5 at% Ti |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.50%/523 K/0.015 MPa/20 min |

71.1 |

Abs: 4.20%/373 K/1.0 MPa/15 min |

[57] |

|

|

MgH2-5 at% Ti |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.20%/573 K/0.03 MPa/15 min |

Abs: 6.70%/ 573 K/0.8 MPa/15 min |

[58] |

||

|

Mg-5% Ti |

Chemical vapor synthesis |

104 |

[59] |

|||

|

Mg-14 at% Ti |

Gas phase condensation |

35 |

52 |

[60] |

||

|

Mg-22 at% Ti |

31 |

47 |

||||

|

MgH2-15% Ti |

Ball milling |

Des: 0.12%/573 K/1 bar/60 min |

Abs: 3.48%/573 K/12 bar/60 min |

[61] |

||

|

Mg0.9Ti0.1 |

Ball milling |

76 |

Abs: 6.62% (after milling) |

[62] |

||

|

Mg0.75Ti0.25 |

Ball milling |

88 |

Abs: 6.18% (after milling) |

|||

|

Mg0.5Ti0.5 |

Ball milling |

91 |

Abs: 5.21% (after milling) |

|||

|

MgH2-20% Ti |

Ball milling |

72 ± 3 |

[63] |

|||

|

MgH2-coated Ti |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.00%/250 °C/15 min (TPD) Des Temperature: 175 °C |

[64] |

|||

|

Mg83.5Ti16.5 |

Inert gas condensation |

Des: 2.50%/300 °C/0.15 bar/2 min |

Abs: 2.20%/300 °C/9 bar/1 min |

[65] |

||

|

15Mg-Ti |

Chemical method |

72.2 |

[66] |

|||

|

MgH2-4 mol% TiH2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 0.70%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

Abs: 6.10%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

[55] |

||

|

MgH2-5 at% TiH2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.80%/270 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 235.5 °C |

67.24 |

Abs: 2.70%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

10MgH2-TiH2 |

Ball milling |

73 |

[67] |

|||

|

7MgH2-TiH2 |

Ball milling |

71 |

[68] |

|||

|

4MgH2-TiH2 |

Ball milling |

68 |

[68] |

|||

|

MgH2-10 mol% TiH2 |

Ball milling |

Abs: 5.70%/240 °C/2 MPa/200 s |

16.4 |

[69] |

||

|

MgH2-10% TiH2 |

Ball milling |

24.2 |

[70] |

|||

|

MgH2-10% TiH2 |

Ball milling |

17.9 |

[71] |

|||

|

Mg-9.2% TiH1.971-3.7% TiH1.5 |

Ball milling |

Des: 4.10%/573 K/100 Pa/20 min |

46.2 |

Abs: 4.30%/298 K/4 MPa/10 min |

12.5 |

[72] |

|

Mg0.65Ti0.35D1.2 |

Ball milling |

17 |

[73] |

|||

|

Titanium Oxides |

||||||

|

MgH2-10% TiO2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 6.00%/300 °C/vacuum/20 min |

Abs: 6.00%/300 °C/0.84 MPa/5 min |

[74] |

||

|

Mg-20% TiO2 |

Reactive ball milling |

Des: 4.40%/350 °C/1 bar/8.5 min |

Abs: 3.80%/350 °C/20 bar/2 min |

[75] |

||

|

MgH2-6% TiO2 |

Ball milling |

145.8 ± 14.2 |

[76] |

|||

|

MgH2 + 10% TiO2 |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 200 °C |

75.50 |

[77] |

||

|

Titanium Halides |

||||||

|

MgH2-10% TiF4 |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 216.7 °C |

71 |

(Des: 6.6%) |

[78] |

|

|

MgH2-10% TiF4 |

Ball milling (2 h, argon) |

Des Temperature: 154 °C |

70 |

[79] |

||

|

MgH2 + 10% TiF4 |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 150 °C |

70 |

[77] |

||

|

MgH2-4 mol% TiF3 |

Ball milling |

Des: 4.50%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

Abs: 5.10%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

[55] |

||

|

MgH2-4 mol% TiCl3 |

Ball milling |

Des: 3.70%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

Abs: 5.30%/573 K/2 MPa/5 min |

[55] |

||

|

MgH2-7% TiCl3 |

Ball milling |

Des temperature: 274 °C |

85 |

[80] |

||

|

Titanium Alloys |

||||||

|

MgH2-5a% TiAl |

Ball milling |

Des: 4.90%/270 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 219.6 °C |

65.08 |

Abs: 2.50%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

MgH2-5 a% Ti3Al |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 232.3 °C |

70.61 |

[56] |

||

|

Mg85Al7.5Ti7.5 |

DC-magnetron co-sputtering |

Des: 5.30%/200 °C/vacuum/20 min |

Abs: 5.60%/200 °C/3 bar/0.5 min |

[81] |

||

|

Mg0.63Ti0.27Si0.10D1.1 |

Ball milling |

27 |

[73] |

|||

|

MgH2-5 at%TiNi |

Ball milling |

Des Temperature: 242.4 °C |

73.09 |

[56] |

||

|

15Mg-Ti-0.75Ni |

Chemical method |

63.7 |

[66] |

|||

|

Mg0.63Ti0.27Ni0.10D1.3 |

Ball milling |

21 |

[73] |

|||

|

MgH2-5at%TiNb |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.90%/27 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 231.3 °C |

71.72 |

Abs: 2.80%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

MgH2-5at% Cr-5a% Ti |

Film |

Des: 6.00%/200 °C/5 mbar/25 min |

Abs: 6.20%/200 °C/3 bar/10 min |

[82] |

||

|

MgH2-7 at% Cr-13 at% Ti |

Film |

Des: 5.00%/200 °C/5 mbar/25 min |

Abs: 5.60%/200 °C/3 bar/10 min |

|||

|

MgH2-5 at% TiFe |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.20%/270 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 237.7 °C |

72.63 |

Abs: 3.00%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

MgH2-5% FeTi |

Ball milling |

Abs: 2.30%/150 °C/2 MPa/5 min |

21 |

[83] |

||

|

MgH2-5 at% TiMn2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 4.80%/270 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 219.7 °C |

74.22 |

Abs: 3.20%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

MgH2-10% TiMn2 |

Ball milling |

22.6 |

[70] |

|||

|

MgH2-5% VTi |

Ball milling |

Abs: 3.30%/150 °C/2 MPa/5 min |

10.4 |

[83] |

||

|

Mg87.5Ti9.6V2.9 |

Hydrogen plasma metal reaction |

Des: 4.00%/300 °C/1 mbar/5 min |

73.8 |

Abs: 4.80%/200 °C/40 bar/5 min |

29.2 |

[84] |

|

MgH2-5 at% TiVMn |

Ball milling |

Des: 5.70%/270 °C/0.12 bar/10 min Des Temperature: 216.7 °C |

85.20 |

Abs: 3.00%/25 °C/1 bar/250 min |

[56] |

|

|

Multiple Catalysts |

||||||

|

Mg-10% Ti-10% Pd |

Ball milling |

114 ± 4 |

[85] |

|||

|

Mg-TiH1.971-TiH1.5-ZrH1.66 |

Arc melting |

36.6 |

21.2 |

[86] |

||

|

Mg0.9Ti0.1 + 5% C |

Ball milling |

88 |

Abs: 6.43% (after milling) |

[62] |

||

|

MgH2-6% NiTiO3 |

Ball milling |

74 ± 4 |

[87] |

|||

|

MgH2-6% CoTiO3 |

Ball milling |

100 ± 2 |

||||

|

MgH2-10 mol% TiH2-6 mol% TiO2 |

Ball milling |

118 |

[88] |

|||

|

MgH2-5% VTi-CNTs |

Ball milling |

Abs: 5.10%/150 °C/2 MPa/5 min |

10.2 |

[83] |

||

|

MgH2-5% FeTi-CNTs |

Ball milling |

Abs: 0.60%/150 °C/2 MPa/5 min |

65.5 |

[83] |

||

|

MgH2-10% Ni-TiO2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 6.50%/265 °C/0.02 bar/7 min |

43.7 ± 1.5 |

Abs: 5.00%/100 °C/60 bar/7 min |

[76] |

|

|

MgH2-4% Ni-6% TiO2 |

Ball milling |

91.6 ± 8.5 |

[76] |

|||

|

MgH2-10% Co-TiO2 |

Ball milling |

Des: 6.20%/250 °C/0.02 bar/15 min |

77 |

Abs: 4.24%/100 °C/60 bar/10 min |

[89] |

|

3.2. Catalytic Effects of Ti-Based Compounds

4. Synthetic Approaches

5. Mechanisms of Catalysis

References

- Harapan, H.; Mudatsir, M.; Yufika, A.; Nawawi, Y.; Wahyuniati, N.; Anwar, S.; Yusri, F.; Haryanti, N.; Wijayanti, N.P.; Rizal, R.; et al. Hydrogen and fuel cells: Towards a sustainable energy future. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4356–4362.

- Felderhoff, M.; Weidenthaler, C.; von Helmolt, R.; Eberle, U. Hydrogen storage: The remaining scientific and technological challenges. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2007, 9, 2643–2653.

- Jollibois, M.P. Sur la formule du derive organo-magnesien et sur l’hydrure de magnesium. Compt. Rend. 1912, 155, 353–355.

- Dymova, T.N.; Sterlyadkina, Z.K.; Safronov, V.G. On the preparation of magnesium hydride. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 1961, 6, 763–767.

- Schlapbach, L.; Züttel, A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature 2001, 414, 353–358.

- Fang, Z.Z.; Zhou, C.; Fan, P.; Udell, K.S.; Bowman, R.C.; Vajo, J.J.; Purewal, J.J.; Kekelia, B. Metal hydrides based high energy density thermal battery. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 645, S184–S189.

- Li, J.; Li, B.; Shao, H.; Li, W.; Lin, H. Catalysis and downsizing in Mg-based hydrogen storage materials. Catalysts 2018, 8, 89.

- Sadhasivam, T.; Kim, H.-T.; Jung, S.; Roh, S.-H.; Park, J.-H.; Jung, H.-Y. Dimensional effects of nanostructured Mg/MgH2 for hydrogen storage applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 523–534.

- Cheng, F.; Tao, Z.; Liang, J.; Chen, J. Efficient hydrogen storage with the combination of lightweight Mg/MgH2 and nanostructures. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7334–7343.

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Gao, M.; Pan, H. Empowering hydrogen storage performance of MgH2 by nanoengineering and nanocatalysis. Mater. Today Nano 2020, 9, 100064.

- Aguey-Zinsou, K.-F.; Ares-Fernández, J.-R. Hydrogen in magnesium: New perspectives toward functional stores. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 526–543.

- de Jongh, P.E.; Adelhelm, P. Nanosizing and nanoconfinement: New strategies towards meeting hydrogen storage goals. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 1332–1348.

- Shao, H.; He, L.; Lin, H.; Li, H.-W. Progress and Trends in Magnesium-Based Materials for Energy-Storage Research: A Review. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 445–458.

- Webb, C.A. A review of catalyst-enhanced magnesium hydride as a hydrogen storage material. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2015, 84, 96–106.

- Yartys, V.; Lototskyy, M.; Akiba, E.; Albert, R.; Antonov, V.; Ares, J.; Baricco, M.; Bourgeois, N.; Buckley, C.; Von Colbe, J.B.; et al. Magnesium based materials for hydrogen based energy storage: Past, present and future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7809–7859.

- Luo, Q.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Liu, B.; Shao, H.; Li, Q. Kinetics in Mg-based hydrogen storage materials: Enhancement and mechanism. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2019, 7, 58–71.

- Xie, X.; Chen, M.; Hu, M.; Wang, B.; Yu, R.; Liu, T. Recent advances in magnesium-based hydrogen storage materials with multiple catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 10694–10712.

- Zhang, Q.; Zang, L.; Huang, Y.; Gao, P.; Jiao, L.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y. Improved hydrogen storage properties of MgH2 with Ni-based compounds. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 24247–24255.

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Ye, J.; Yuan, B.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L. Recent advances on the thermal destabilization of Mg-based hydrogen storage materials. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 408–428.

- Stampfer, J.F.; Holley, C.E.; Suttle, J.F. The magnesium-hydrogen system1-3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 3504–3508.

- Jain, I.; Lal, C.; Jain, A. Hydrogen storage in Mg: A most promising material. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 5133–5144.

- Vajeeston, P.; Ravindran, P.; Hauback, B.C.; Fjellvåg, H.; Kjekshus, A.; Furuseth, S.; Hanfland, M. Structural stability and pressure-induced phase transitions in MgH2. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 224102.

- Dornheim, M.; Doppiu, S.; Barkhordarian, G.; Boesenberg, U.; Klassen, T.; Gutfleisch, O.; Bormann, R. Hydrogen storage in magnesium-based hydrides and hydride composites. Scr. Mater. 2007, 56, 841–846.

- Vajeeston, P.; Ravindran, P.; Kjekshus, A.; Fjellvag, H. Pressure-induced structural transitions in MgH2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89, 175506.

- Varin, R.A.; Czujko, T.; Wronski, Z. Particle size, grain size and γ-MgH2 effects on the desorption properties of nanocrystalline commercial magnesium hydride processed by controlled mechanical milling. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 3856–3865.

- Felderhoff, M.; Bogdanović, B. High temperature metal hydrides as heat storage materials for solar and related applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 325–344.

- Satyapal, S.; Petrovic, J.; Read, C.; Thomas, G.; Ordaz, G. The U.S. Department of Energy’s National Hydrogen Storage Project: Progress towards meeting hydrogen-powered vehicle requirements. Catal. Today 2007, 120, 246–256.

- Kohno, T.; Tsuruta, S.; Kanda, M. The hydrogen storage properties of new Mg2Ni alloy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143, 198–199.

- Shao, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Li, X. Preparation and hydrogen storage properties of nanostructured Mg2Cu alloy. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 2211–2217.

- Bououdina, M.; Guo, Z.X. Comparative study of mechanical alloying of (Mg+ Al) and (Mg+ Al+ Ni) mixtures for hydrogen storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 336, 222–231.

- Bruzzone, G.; Costa, G.; Ferretti, M.; Olcese, G. Hydrogen storage in Mg51Zn20. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1983, 8, 459–461.

- Chaudhary, A.-L.; Sheppard, D.A.; Paskevicius, M.; Webb, C.J.; Gray, E.M.; Buckley, C.E. Mg2Si Nanoparticle Synthesis for High Pressure Hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 1240–1247.

- Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X. Thermodynamic and kinetic destabilization of magnesium hydride using Mg-In solid solution alloys. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10982–10985.

- Si, T.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, D.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, M. Enhanced hydrogen storage properties of a Mg–Ag alloy with solid dissolution of indium: A comparative study. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 8581–8589.

- Spassov, T.; Lyubenova, L.; Köster, U.; Baró, M.D. Mg–Ni–RE nanocrystalline alloys for hydrogen storage. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 794–799.

- Asano, K.; Enoki, H.; Akiba, E. Effect of Li Addition on Synthesis of Mg-Ti BCC Alloys by means of Ball Milling. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 121–126.

- Asano, K.; Akiba, E. Direct synthesis of Mg–Ti–H FCC hydrides from MgH2 and Ti by means of ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 481, L8–L11.

- Asano, K.; Enoki, H.; Akiba, E. Synthesis of HCP, FCC and BCC structure alloys in the Mg–Ti binary system by means of ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 480, 558–563.

- Asano, K.; Enoki, H.; Akiba, E. Synthesis process of Mg–Ti BCC alloys by means of ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 486, 115–123.

- Vermeulen, P.; van Thiel, E.F.; Notten, P.H. Ternary MgTiX-alloys: A promising route towards low-temperature, high-capacity, hydrogen-storage materials. Chemistry 2007, 13, 9892–9898.

- Jain, A.; Miyaoka, H.; Ichikawa, T. Destabilization of lithium hydride by the substitution of group 14 elements: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 5969–5978.

- Wagemans, R.W.P.; van Lenthe, J.H.; de Jongh, P.E.; van Dillen, A.J.; de Jong, K.P. Hydrogen storage in magnesium clusters: Quantum chemical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16675–16680.

- Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Qu, H. Stress/strain effects on thermodynamic properties of magnesium hydride: A brief review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 16603–16610.

- Berube, V.; Chen, G.; Dresselhaus, M. Impact of nanostructuring on the enthalpy of formation of metal hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 33, 4122–4131.

- Zhu, M.; Lu, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, H. Thermodynamic Tuning of Mg-Based Hydrogen Storage Alloys: A Review. Materials 2013, 6, 4654–4674.

- Bououdina, M.; Grant, D.; Walker, G. Review on hydrogen absorbing materials—structure, microstructure, and thermodynamic properties. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 177–182.

- Sun, Y.; Shen, C.; Lai, Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.-W.; Aguey-Zinsou, K.-F. Tailoring magnesium based materials for hydrogen storage through synthesis: Current state of the art. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 168–198.

- Pozzo, M.; Alfè, D. Hydrogen dissociation and diffusion on transition metal (=Ti, Zr, V, Fe, Ru, Co, Rh, Ni, Pd, Cu, Ag)-doped Mg, 0001, surfaces. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 1922–1930.

- Pozzo, M.; Alfe, D.; Amieiro, A.; French, S.; Pratt, A. Hydrogen dissociation and diffusion on Ni- and Ti-doped Mg, 0001, surfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 094703.

- Spatz, P.; Aebischer, H.A.; Krozer, A.; Schlapbach, L. The Diffusion of H in Mg and the Nucleation and Growth of MgH2 in Thin Films*. Z. Phys. Chem. 1993, 181, 393–397.

- Zhou, C. A Study of Advanced Magnesium-Based Hydride and Development of a Metal Hydride Thermal Battery System. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2015.

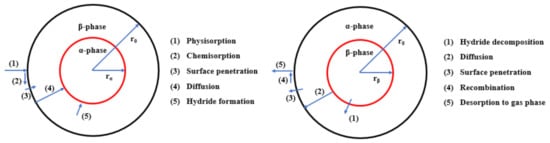

- Jain, A.; Agarwal, S.; Ichikawa, T. Catalytic tuning of sorption kinetics of lightweight hydrides: A review of the materials and mechanism. Catalysts 2018, 8, 651.

- Pasquini, L.; Callini, E.; Brighi, M.; Boscherini, F.; Montone, A.; Jensen, T.R.; Maurizio, C.; Antisari, M.V.; Bonetti, E. Magnesium nanoparticles with transition metal decoration for hydrogen storage. J. Nanopart. Res. 2011, 13, 5727–5737.

- Vincent, S.; Lang, J.; Huot, J. Addition of catalysts to magnesium hydride by means of cold rolling. J. Alloys Compd. 2012, 512, 290–295.

- Ma, L.-P.; Wang, P.; Kang, X.-D.; Cheng, H.-M. Preliminary investigation on the catalytic mechanism of TiF3 additive in MgH2–TiF3 H-storage system. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 22, 1779–1786.

- Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.Z.; Ren, C.; Li, J.; Lu, J. Effect of Ti Intermetallic catalysts on hydrogen storage properties of magnesium hydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 12973–12980.

- Liang, G.; Huot, J.; Boily, S.; Neste, A.V.; Schulz, R. Catalytic effect of transition metals on hydrogen sorption in nanocrystalline ball milled MgH–Tm (Tm = Ti, V, Mn, Fe and Ni). J. Alloys Compd. 1999, 292, 247–252.

- Rizo-Acosta, P.; Cuevas, F.; Latroche, M. Hydrides of early transition metals as catalysts and grain growth inhibitors for enhanced reversible hydrogen storage in nanostructured magnesium. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 23064–23075.

- Choi, Y.J.; Choi, J.W.; Sohn, H.Y.; Ryu, T.; Hwang, K.S.; Fang, Z.Z. Chemical vapor synthesis of Mg–Ti nanopowder mixture as a hydrogen storage material. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 7700–7706.

- Patelli, N.; Migliori, A.; Pasquini, L. Reversible metal-hydride transformation in Mg-Ti-H nanoparticles at remarkably low temperatures. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 1325–1333.

- Choi, E.; Song, M.Y. Hydriding and dehydriding features of a titanium-added magnesium hydride composite, materials. Science 2020, 26, 199–204.

- Lotoskyy, M.; Denys, R.; Yartys, V.A.; Eriksen, J.; Goh, J.; Nyamsi, S.N.; Sita, C.; Cummings, F. An outstanding effect of graphite in nano-MgH2-TiH2 on hydrogen storage performance dagger. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 10740–10754.

- Croston, D.; Grant, D.; Walker, G. The catalytic effect of titanium oxide based additives on the dehydrogenation and hydrogenation of milled MgH2. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 492, 251–258.

- Cui, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Ouyang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, D.; Yao, X.; Zhu, M. Remarkable enhancement in dehydrogenation of MgH2 by a nano-coating of multi-valence Ti-based catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 492, 251–258.

- Calizzi, M.; Venturi, F.; Ponthieu, M.; Cuevas, F.; Morandi, V.; Perkisas, T.; Bals, S.; Pasquini, L. Gas-phase synthesis of Mg–Ti nanoparticles for solid-state hydrogen storage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 141–148.

- Lu, C.; Zou, J.; Shi, X.; Zeng, X.; Ding, W. Synthesis and hydrogen storage properties of core–shell structured binary Ti and ternary Ni composites. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 2239–2247.

- Choi, Y.J.; Lu, J.; Sohn, H.Y.; Fang, Z.Z.; Rönnebro, E. Effect of milling parameters on the dehydrogenation properties of the Mg−Ti−H system. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 19344–19350.

- Choi, Y.J.; Lu, J.; Sohn, H.Y.; Fang, Z.Z. Hydrogen storage properties of the Mg–Ti–H system prepared by high-energy–high-pressure reactive milling. J. Power Sources 2008, 180, 491–497.

- Lu, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Fang, Z.Z.; Sohn, H.Y.; Rönnebro, E. Hydrogenation of Nanocrystalline Mg at Room Temperature in the Presence of TiH2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6616–6617.

- Li, J.; Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.Z.; Bowman, R.C., Jr.; Lu, J.; Ren, C. Isothermal hydrogenation kinetics of ball-milled nano-catalyzed magnesium hydride. Materialia 2019, 5, 100227.

- Li, J.; Fan, P.; Fang, Z.Z.; Zhou, C. Kinetics of isothermal hydrogenation of magnesium with TiH2 additive. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 7373–7381.

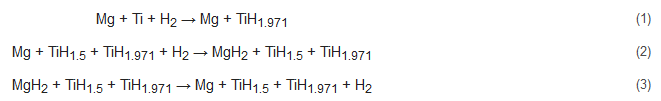

- Liu, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, F.; Li, X. Enhanced hydrogen storage properties of magnesium by the synergic catalytic effect of TiH1.971 and TiH1.5 nanoparticles at room temperature. J. Power Sources 2014, 267, 69–77.

- Manivasagam, T.G.; Magusin, P.C.M.M.; Iliksu, M.; Notten, P.H.L. Influence of Nickel and Silicon Addition on the Deuterium Siting and Mobility in fcc Mg–Ti Hydride Studied with2H MAS NMR. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 10606–10615.

- Oelerich, W.; Klassen, T.; Bormann, R. Mg-based hydrogen storage materials with improved hydrogen sorption. Mater. Trans. 2001, 42, 1588–1592.

- Wang, P.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H.; Ding, B.; Hu, Z. Hydrogenation characteristics of Mg–TiO (rutile) composite. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 313, 218–223.

- Chen, M.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Excellent synergistic catalytic mechanism of in-situ formed nanosized Mg2Ni and multiple valence titanium for improved hydrogen desorption properties of magnesium hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 1750–1759.

- Jangir, M.; Gattia, D.M.; Peter, A.; Jain, I.P. Effect of Ti-Additives on Hydrogenation/Dehydrogenation Properties of MgH2. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Concentrator Photovoltaic Systems (CPV-15), Fes, Marocco, 25–27 March 2019; AIP Publishing: College Park, MD, USA, 2019; Volume 2145, p. 020006.

- Jain, A.; Agarwal, S.; Kumar, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Miyaoka, H.; Kojima, Y.; Ichikawa, T. How does TiF4 affect the decomposition of MgH2 and its complex variants?—An XPS investigation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 15543–15551.

- Jangir, M.; Jain, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Lal, C.; Jain, I. Catalytic effect of TiF4 in improving hydrogen storage properties of MgH2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 14178–14183.

- Malka, I.; Czujko, T.; Bystrzycki, J. Catalytic effect of halide additives ball milled with magnesium hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 1706–1712.

- Kalisvaart, W.; Harrower, C.; Haagsma, J.; Zahiri, B.; Luber, E.; Ophus, C.; Poirier, E.; Fritzsche, H.; Mitlin, D. Hydrogen storage in binary and ternary Mg-based alloys: A comprehensive experimental study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 2091–2103.

- Zahiri, B.; Amirkhiz, B.S.; Mitlin, D. Hydrogen storage cycling of MgH2 thin film nanocomposites catalyzed by bimetallic Cr Ti. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 083106.

- Yao, X.; Wu, C.; Du, A.; Zou, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, P.; Cheng, H.; Smith, S.C.; Lu, G. Metallic and carbon nanotube-catalyzed coupling of hydrogenation in magnesium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 15650–15654.

- Liu, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y. Enhanced hydrogen storage properties of Mg–Ti–V nanocomposite at moderate temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 22419–22425.

- Berlouis, L.E.A.; Honnor, P.; Hall, P.J.; Morris, S.; Dodd, S.B. An investigation of the effect of Ti, Pd and Zr on the dehydriding kinetics of MgH2. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 6403–6408.

- Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Xu, L.; Li, X.I. Improved kinetics of nanoparticle-decorated Mg-Ti-Zr nanocomposite for hydrogen storage at moderate temperatures. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 206, 21–28.

- Huang, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Fan, X.; Tang, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, L. Synergistic catalytic activity of porous rod-like TMTiO3 (TM = Ni and Co) for reversible hydrogen storage of magnesium hydride. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 27973–27982.

- Daryani, M.; Simchi, A.; Sadati, M.; Hosseini, H.M.; Targholizadeh, H.; Khakbiz, M. Effects of Ti-based catalysts on hydrogen desorption kinetics of nanostructured magnesium hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 21007–21014.

- Chen, M.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L. Highly dispersed metal nanoparticles on TiO2 acted as nano redox reactor and its synergistic catalysis on the hydrogen storage properties of magnesium hydride. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 15100–15109.

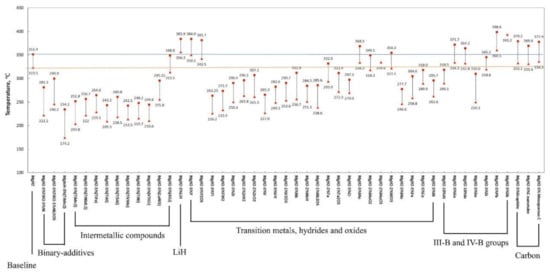

- Zhou, C.; Fang, Z.Z.; Sun, P. An experimental survey of additives for improving dehydrogenation properties of magnesium hydride. J. Power Sources 2015, 278, 38–42.

- Cui, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, L.; Sun, D.; Zhu, M.; Yao, X. Mg–TM (TM: Ti, Nb, V, Co, Mo or Ni) core–shell like nanostructures: Synthesis, hydrogen storage performance and catalytic mechanism. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 9645–9655.

- Lu, J.; Choi, Y.J.; Fang, Z.Z.; Sohn, H.Y.; Rönnebro, E. Hydrogen storage properties of nanosized MgH2-0.1TiH2 prepared by ultrahigh-energy-high-pressure milling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15843–15852.

- Ponthieu, M.; Cuevas, F.; Fernández, J.F.; Laversenne, L.; Porcher, F.; Latroche, M. Structural properties and reversible deuterium loading of MgD2–TiD2 nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 18851–18862.

- Emery, S.B.; Sorte, E.G.; Bowman, R.C.; Fang, Z.Z.; Ren, C.; Majzoub, E.H.; Conradi, M.S. Detection of fluorite-structured MgD2/TiD2: Deuterium NMR. J. Phys. Chem. 2015, 119, 7656–7661.

- Kyoi, D.; Sato, T.; Rönnebro, E.; Kitamura, N.; Ueda, A.; Ito, M.; Katsuyama, S.; Hara, S.; Noréus, D.; Sakai, T. A new ternary magnesium–titanium hydride Mg7TiHx with hydrogen desorption properties better than both binary magnesium and titanium hydrides. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 372, 213–217.

- Oelerich, W.; Klassen, T.; Bormann, R. Metal oxides as catalysts for improved hydrogen sorption in nanocrystalline Mg-based materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2001, 315, 237–242.

- Pukazhselvan, D.; Nasani, N.; Correia, P.; Carbó-Argibay, E.; Otero-Irurueta, G.; Stroppa, D.G.; Fagg, D.P. Evolution of reduced Ti containing phase(s) in MgH2/TiO2 system and its effect on the hydrogen storage behavior of MgH2. J. Power Sources 2017, 362, 174–183.

- Zhang, M.; Xiao, X.; Luo, B.; Liu, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, L. Superior de/hydrogenation performances of MgH2 catalyzed by 3D flower-like TiO2@C nanostructures. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 46, 191–198.

- Berezovets, V.; Denys, R.; Zavaliy, I.; Kosarchyn, Y. Effect of Ti-based nanosized additives on the hydrogen storage properties of MgH2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021.

- Jin, S.-A.; Shim, J.-H.; Cho, Y.W.; Yi, K.-W. Dehydrogenation and hydrogenation characteristics of MgH2 with transition metal fluorides. J. Power Sources 2007, 172, 859–862.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, L.; Yuan, H. Catalytic effects of different Ti-based materials on dehydrogenation performances of MgH2. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 645, S509–S512.

- Guoxian, L.; Erde, W.; Shoushi, F. Hydrogen absorption and desorption characteristics of mechanically milled Mg-35 wt%FeTi1.2 powders. J. Alloys Compd. 1995, 223, 111–114.

- Reule, H.; Hirscher, M.; Weißhardt, A.; Kronmüller, H. Hydrogen desorption properties of mechanically alloyed MgH2 composite materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2000, 305, 246–252.

- Cui, N.; Luan, B.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H.K.; Dou, S.X. Synthesis and electrode characteristics of the new composite alloys Mg2Ni-xwt%Ti2Ni. J. Alloys Compd. 1996, 240, 229–234.

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, A.; Ding, B.; Hu, Z. Preparation and hydriding/dehydriding properties of mechanically milled Mg–30 wt% TiMn1.5 composite. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 354, 296–302.

- El-Eskandarany, M.S.; Shaban, E.; Aldakheel, F.; Alkandary, A.; Behbehani, M.; Al-Saidi, M. Synthetic nanocomposite MgH2/5 wt. % TiMn2 powders for solid-hydrogen storage tank integrated with PEM fuel cell. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13296.

- El-Eskandarany, M.S.; Al-Ajmi, F.; Banyan, M.; Al-Duweesh, A. Synergetic effect of reactive ball milling and cold pressing on enhancing the hydrogen storage behavior of nanocomposite MgH2/10 wt% TiMn2 binary system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 26428–26443.

- Dai, J.H.; Jiang, X.W.; Song, Y. Stability and hydrogen adsorption properties of Mg/TiMn2 interface by first principles calculation. Surf. Sci. 2016, 653, 22–26.

- Hanada, N.; Ichikawa, T.; Fujii, H. Catalytic effect of Ni nano-particle and Nb oxide on H-desorption properties in MgH2 prepared by ball milling. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 404–406, 716–719.

- Pourabdoli, M.; Raygan, S.; Abdizadeh, H.; Uner, D. A comparative study for synthesis methods of nano-structured (9Ni–2Mg–Y) alloy catalysts and effect of the produced alloy on hydrogen desorption properties of MgH2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 16090–16097.

- Elanski, D.; Lim, J.-W.; Mimura, K.; Isshiki, M. Thermodynamic estimation of hydride formation during hydrogen plasma arc melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2007, 439, 210–214.

- Elanski, D.; Lim, J.-W.; Mimura, K.; Isshiki, M. Complex hydrides for energy storage, conversion, and utilization. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1902757.

- Martin, M.; Gommel, C.; Borkhart, C.; Fromm, E. Absorption and desorption kinetics of hydrogen storage alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 1996, 238, 193–201.

- Hollenbach, D.; Salpeter, E.E. Surface recombination of hydrogen molecules. Astrophys. J. 1971, 163, 155.