| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Efthimis Kotenidis | + 4207 word(s) | 4207 | 2021-05-27 10:37:59 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | + 8 word(s) | 4215 | 2021-05-31 05:05:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

A term that attempts to describe the procedures that have been brought about by recent technological changes in the field of journalism. Characterized by researchers as “the process of using software or algorithms to automatically generate news stories" (Graefe 2016) and “the combination of algorithms, data, and knowledge from the social sciences to supplement the accountability function of journalism” (Hamilton and Turner 2009).

1. Introduction

2. Definition of Algorithmic Journalism

3. Areas of Application

-

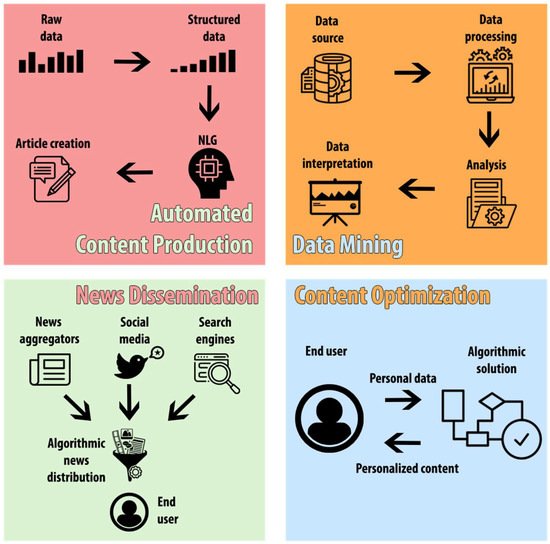

Automated content production;

-

Data mining;

-

News dissemination;

-

Content optimization.

3.1 Automated contend production

The automation of the news creation process is perhaps the most important - and as a result the most controversial - of all the fields of application for algorithmic technology in journalism (Montal and Reich 2017; Schapals and Pmontaorlezza 2020). In the grand scheme of things, this particular field of application is considered a relatively recent development in the field of journalism (Ali and Hassoun, 2019; Graefe 2016) and it consists mainly of algorithms and automated software that are capable of creating news stories on their own (Diakopoulos 2019).

One of the most well known examples of early applications for automatic content production is that of "Quakebot", a program that was created on behalf of the Los Angeles Times in 2014. Its purpose was to closely monitor data from the US Geological Survey in an attempt to identify instances on seismic activity and proceed to write and publish simple reports on them (Otter 2017). Since then, automatic content production has taken major steps forward, to the point where some of the biggest contributors to the industry such as Forbes and The New York Times often rely on algorithmic production for their content, with the end result being almost impossible to distinguish from human writing (Clerwall 2014).

The basis for the innovations in automated content production is a technology called "Natural Language Generation" or NLG for short. Natural language generation is defined as "the automatic creation of text from digital structured data" (Caswell and Dörr 2018) and it is a technology that first made its appearance in the 1950s within the context of machine translation (Reiter 2010). NLG has seen exponential growth in the past few years and in light of these developments many industries begun to utilize it alongside artificial intelligence to further improve their products and services, with the news media industry being no exception to this rule (Diakopoulos 2019).

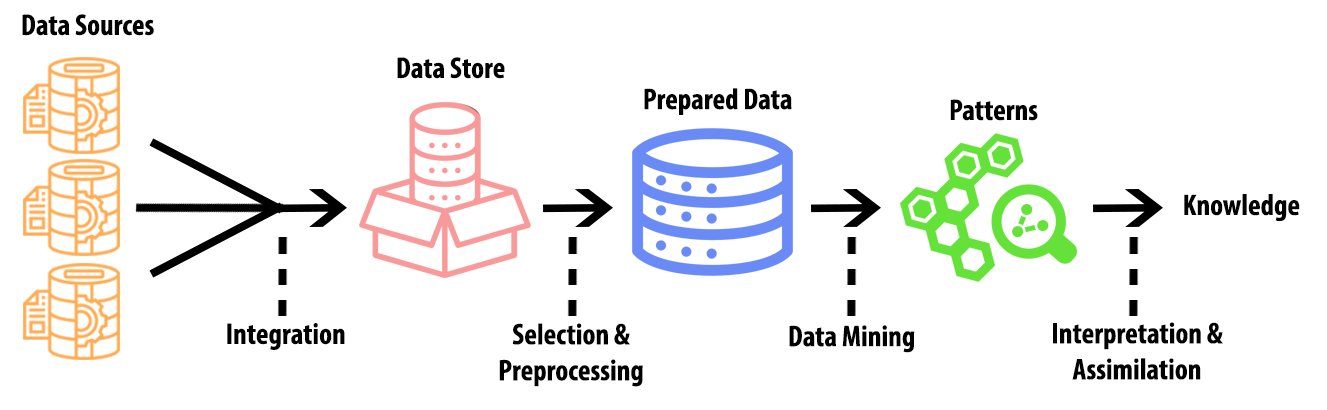

3.2 Data Mining

3.3 News dissemination

3.4 Content Optimization

References

- Pavlik, John. 2000. The impact of technology on journalism. Journalism Studies 1: 229–37.

- Deuze, Mark, and Tamara Witschge. 2018. Beyond journalism: Theorizing the transformation of journalism. Journalism 19: 165–81.

- Dörr, Konstantin. Nicholas. 2015. Mapping the field of algorithmic journalism. Digital Journalism.

- Spyridou, Lia-Paschalia, Maria Matsiola, Andreas Veglis, George Kalliris, and Charalambos Dimoulas. 2013. Journalism in a state of flux: Journalists as agents of technology innovation and emerging news practices. International Communication Gazette 75: 76–98.

- Frey, Carl Benedikt, and Michael A. Osborne. 2017. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114: 254–80.

- Graefe, Andreas. 2016. Guide to automated journalism. Tow Center for Digital Journalism.

- Van Dalen, Arjen. 2012. The algorithms behind the headlines: How machine-written news redefines the core skills of human journalists. Journalism Practice 6: 648–58.

- Anderson, C. W. 2012. Towards a sociology of computational and algorithmic journalism. New Media & Society 15: 1005–21.

- Hamilton, James T., and Fred Turner. 2009. Accountability through Algorithm. Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences Summer Workshop. Available online: (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Garrison, Bruce. 1998. Computer-Assisted Reporting, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2011. A Functional Roadmap for Innovation in Computational Journalism. Nick Diakopoulos [Blog Post]. Available online: (accessed on 6 February 2021).

- Lindén, Carl-Gustav, Hanna Tuulonen, Asta Bäck, Nicholas Diakopoulos, Mark Granroth-Wilding, Lauri Haapanen, Leo Leppänen, Magnus Melin, Tom Moring, Myriam Munezero, and et al. 2019. News Automation: The Rewards, Risks and Realities of Machine Journalism. WAN-IFRA Report. Available online: (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Lindén, Carl-Gustav. 2017. Algorithms for journalism: The future of news work. The Journal of Media Innovations.

- Ali, Waleed, and Mohamed Hassoun. 2019. Artificial intelligence and automated journalism: Contemporary challenges and new opportunities. International Journal of Media, Journalism and Mass Communication 5: 40–49.

- Milosavljević, Marko, and Igor Vobič. 2019. ‘Our task is to demystify fears’: Analysing newsroom management of automation in journalism. Journalism.

- Glahn, Harry R. 1970. Computer-produced worded forecasts. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 51: 1126–32.

- Clerwall, Christer. 2014. Enter the robot journalist: Users’ perceptions of automated content. Journalism Practice 8: 519–31.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Zangana, Abdulsamad. 2017. The Impact of New Technology on the News Production Process in the Newsroom. Ph.D. thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. Available online: (accessed on 14 February 2021).

- Veglis, Andreas, and Theodora A. Maniou. 2019. Chatbots on the rise: A new narrative in journalism. Studies in Media and Communication 7: 1–6.

- Kirley, Elizabeth A. 2016. The robot as cub reporter: Law’s emerging role in cognitive journalism. European journal of Law and Technology 7: 17–18. Available online: (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Hansen, Mark, Meritxell Roca-Sales, Jon M. Keegan, and George King. 2017. Artificial intelligence: Practice and implications for journalism. In Tow Center for Digital Journalism. New York: Columbia University.

- Liu, Xiaomo, Armineh Nourbakhsh, Quanzhi Li, Sameena Shah, Robert Martin, and John Duprey. 2017. Reuters tracer: Toward automated news production using large scale social media data. Paper presented at the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Boston, MA, USA, December 11–14; pp. 1483–93.

- Carlson, Matt. 2015. The robotic reporter: Automated journalism and the redefinition of labor, compositional forms, and journalistic authority. Digital Journalism 3: 416–31.

- Schapals, Aljosha Karim, and Colin Porlezza. 2020. Assistance or resistance? Evaluating the intersection of automated journalism and journalistic role conceptions. Media and Communication 8: 16–26.

- Jamil, Sadia. 2020. Artificial intelligence and journalistic practice: The crossroads of obstacles and opportunities for the Pakistani journalists. Journalism Practice, 1–23.

- Zhu, Yangyong, Ning Zhong, and Yun Xiong. 2009. Data explosion, data nature and dataology. In International Conference on Brain Informatics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 147–58.

- Aljazairi, Sena. 2016. Robot Journalism: Threat or an Opportunity. Master’s thesis, School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden. Available online: (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Chen, Sherry. Y., and Xiaohui Liu. 2004. The contribution of data mining to information science. Journal of Information Science 30: 550–58.

- Bramer, Max. 2007. Principles of Data Mining, 1st ed. London: Springer, vol. 180, p. 2.

- Veglis, Andreas, and Efthimis Kotenidis. 2020. Employing chatbots for data collection in participatory journalism and crisis situations. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies.

- Kitchin, Rob. 2014. Big Data, new epistemologies and paradigm shifts. Big Data & Society 1: 1–12.

- Latar, Noam Lemelshtrich. 2015. The robot journalist in the age of social physics: The end of human journalism? In The New World of Transitioned Media. Cham: Springer, pp. 65–80.

- Kennedy, Helen, and Giles Moss. 2015. Known or knowing publics? Social media data mining and the question of public agency. Big Data & Society 2.

- Hammond, Philip. 2017. From computer-assisted to data-driven: Journalism and Big Data. Journalism 18: 408–24.

- Veglis, Andreas, and Theodora A. Maniou. 2018. The mediated data model of communication flow: Big data and data journalism. KOME: An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry 6: 32–43.

- Gaskins, Benjamin, and Jennifer Jerit. 2012. Internet news: Is it a replacement for traditional media outlets? The International Journal of Press/Politics 17: 190–213.

- Orellana-Rodriguez, Claudia, and Mark T. Keane. 2018. Attention to news and its dissemination on Twitter: A survey. Computer Science Review 29: 74–94.

- Foster, Robin. 2012. News Plurality in a Digital World. Oxford: New Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Cádima, Francisco Rui. 2018. Journalism at the crossroads of the algorithmic turn. Media & Jornalismo 18: 171–85.

- Deuze, Mark. 2005. What is journalism? Professional identity and ideology of journalists reconsidered. Journalism 6: 442–64.

- Carlson, Matt. 2018. Automating judgment? Algorithmic judgment, news knowledge, and journalistic professionalism. New Media & Society 20: 1755–72.

- Lokot, Tetyana, and Nicholas Diakopoulos. 2016. News Bots: Automating news and information dissemination on Twitter. Digital Journalism 4: 682–99.

- Nechushtai, Efrat, and Seth C. Lewis. 2019. What kind of news gatekeepers do we want machines to be? Filter bubbles, fragmentation, and the normative dimensions of algorithmic recommendations. Computers in Human Behavior 90: 298–307.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas. 2015. Algorithmic accountability: Journalistic investigation of computational power structures. Digital Journalism 3: 398–415.

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas, and Michael Koliska. 2017. Algorithmic transparency in the news media. Digital Journalism 5: 809–28.

- Shao, Chengcheng, Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia, Onur Varol, Kai-Cheng Yang, Alessandro Flammini, and Filippo Menczer. 2017. The spread of fake news by social bots. arXiv arXiv:1707.07592.

- Shin, Jieun, and Thomas Valente. 2020. Algorithms and health misinformation: A case study of vaccine books on amazon. Journal of Health Communication 25: 394–401.

- Fernandez, M., and H. Alani. 2018. Online misinformation: Challenges and future directions. Paper presented at the Companion Web Conference 2018, Lyon, France, April 23–27; pp. 595–602.

- Bharat, Krishna, Tomonari Kamba, and Michael Albers. 1998. Personalized, interactive news on the web. Multimedia Systems 6: 349–58.

- Billsus, Daniel, and Michael J. Pazzani. 1999. A hybrid user model for news story classification. In Um99 User Modeling. Vienna: Springer, pp. 99–108.

- Li, Lei, Dingding Wang, Tao Li, Daniel Knox, and Balaji Padmanabhan. 2011. Scene: A scalable two-stage personalized news recommendation system. Paper presented at the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Beijing, China, July 25–29; pp. 125–34.

- Jokela, Sami, Marko Turpeinen, Teppo Kurki, Eerika Savia, and Reijo Sulonen. 2001. The role of structured content in a personalized news service. Paper presented at the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, January 6; pp. 1–10.

- Agarwal, Deepak, Bee-Chung Chen, Pradheep Elango, Nitin Motgi, Seung-Taek Park, Raghu Ramakrishnan, Scott Roy, and Joe Zachariah. 2008. Online models for content optimization. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vancouver: NeurIPS, pp. 17–24.

- Jones, Bronwyn, and Rhianne Jones. 2019. Public service chatbots: Automating conversation with BBC News. Digital Journalism 7: 1032–53.

- Das, Abhinandan S., Mayur Datar, Ashutosh Garg, and Shyam Rajaram. 2007. Google news personalization: Scalable online collaborative filtering. Paper presented at the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web, Banff, AB, Canada, May 8–12; pp. 271–80.

- Powers, Elia. 2017. My news feed is filtered? Awareness of news personalization among college students. Digital Journalism 5: 1315–35.

- Haim, Mario, Andreas Graefe, and Hans-Bernd Brosius. 2018. Burst of the filter bubble? Effects of personalization on the diversity of Google News. Digital Journalism 6: 330–43.

- Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. Echo chambers online?: Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 265–85.