| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KATIA CAILLIAU MAGGIO | + 5287 word(s) | 5287 | 2020-10-07 08:32:34 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3082 word(s) | 2205 | 2020-10-14 05:09:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

Organometallics, such as copper compounds, are cancer chemotherapeutics used alone or in combination with other drugs. A group of copper complexes exerts an effective inhibitory action on topoisomerases, which participate in the regulation of DNA topology. Copper complexes of topoisomerase inhibitors work by different molecular mechanisms that have repercussions on the cell cycle checkpoints and death effectors.

1. Introduction

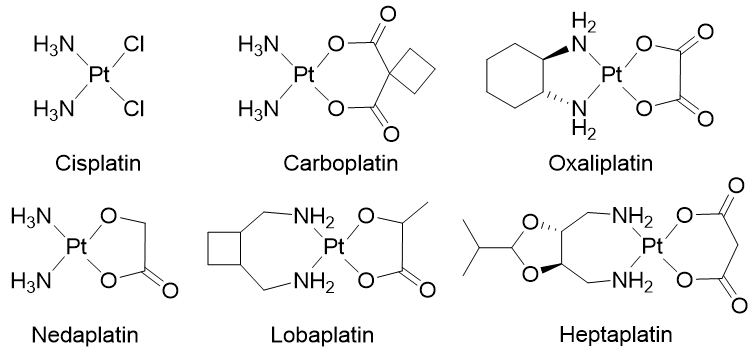

Chemotherapy is a systemic treatment proposed to patients suffering from cancer. It is often a complementary approach to surgery or radiotherapy. The discovery of platinum’s inhibitory effect on tumor cell growth in the 1960s [1] was a milestone for anticancer drug application in medicine [2]. Platinum (II) sets at the center of the squared planar structure of cisplatin and is coordinated with two chlorides and two ammonia molecules in a cis configuration. Cisplatin and its derivative drugs (carboplatin of second generation and oxaliplatin of third generation) are used worldwide in clinical applications and several other platinum analogs (lobaplatin, nedaplatin, and heptaplatin) are approved in several countries (Figure 1) [3][4]. However, serious side effects including toxicities on the kidney, heart, ear, and liver, decrease in immunity, hemorrhage, and gastrointestinal disorders limit the use of platinum derivatives [5][6][7]. The appearance of drug resistances, issuing from acquired or intrinsic multiple genetic and epigenetic changes, has also limited the clinical use of platinum-derived drugs [8]. Platinum-based treatment efficiency is challenged by cross-resistance and multiple changes including a decreased accumulation of the drug, a reduction in DNA–drug adducts, a modification in cell survival gene expression, an alteration of DNA damage repair mechanisms, modifications of transporters, protein trafficking, and altered cell metabolism [9][10][11][12][13][14].

Figure 1. Platinum (II) complexes.

To circumvent drug resistance, a possible approach consists of designing and developing new therapeutic metal-based anticancer drugs [15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. Several transition metals from the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12) and particularly essential trace metals [15][22][23], such as copper [24][25][26][27][28][29], are useful for the implementation of metal-based complexes in anticancer therapies. Copper plays central roles in various cellular processes being an essential micronutrient and an important cofactor for several metalloenzymes involved in mitochondrial metabolism (cytochrome c oxidase), or cellular radical detoxification against reactive oxygen species (ROS) (superoxide dismutase) [30]. Copper is essential for angiogenesis, proliferation, and migration of endothelial cells [31][32][33]. Elevated copper favors tumor growth and metastasis. It is detected in several brain [34], breast [35], colon, prostate [36], and lung [37] tumors and serves as an indicator of the course of the disease [38]. The differences in tumor cells’ responses to copper compared to normal cells laid the foundation of copper complexes’ (CuC) evolution as anticancer agents. Numerous developed CuC contain different sets of N, S, or O ligands and demonstrate high cytotoxicity and efficient antitumor activity [25]. Different mechanisms are involved in copper drugs’ anticancer effect. They act as chelators, and interact with and sequester endogenous copper, reducing its availability for tumor growth and angiogenesis [39]. On the contrary, ionophores trigger intracellular copper accumulation, cytotoxicity, and activate apoptosis inhibitor factor (XIAP) [24][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. Other CuC are proteasome inhibitors [47][48]. Several CuC are actually on clinical trials: a number of copper/disulfiram-based drug combinations for therapy and as diagnostic tools (metastatic breast cancer and germ cell tumor), several casiopeínas compounds and elesclomol (leukemia), and thiosemicarbazone-based copper complexes labeled with a radioactive isotope for positron emission tomography imaging of hypoxia (in head and neck cancers) [49].

The cisplatin DNA-targeting principle of action also conditioned the development of anticancer copper-based drugs [4][23][50]. Antitumor activities of copper-based drugs are based on the interactive properties of both copper and the ligand. Copper toxicity results from its redox capacities (Cu(I) and Cu(II) redox states’ interconversion in oxidation–reduction cycles), the property to displace other ions from the enzyme binding sites, a high DNA binding affinity, and the ability to promote DNA breaks [28][51]. In most cases, copper modifies the backbone of the complexed ligand and grants better DNA affinity, specificity, and stability [52]. Copper derivatives can interact with DNA without the formation of covalent adducts. The noncovalent interactions with DNA include binding along with the major or the minor DNA grooves, intercalation, or electrostatic binding. Some copper-based drugs generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) that overwhelm cellular antioxidant defenses to produce oxidative damages in the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and DNA [53]. An important class of CuC, actually on focus for chemotherapy, inhibits topoisomerases (Top) 1 and 2, resulting in severe DNA damages, cell cycle arrest, and death [40][54][55][56][57]. Chemotherapeutics that target Top as poisons convert a transient DNA-enzyme complex into lethal DNA breaks [58][59][60][61][62]. However, topoisomerase inhibitors’ activity and their multifaceted binding modes to DNA, the effects, and the modulations they produce on the control of cancer cell division necessitate better understanding to optimize their efficiency.

2. Copper Complexes as Topoisomerases Inhibitors

DNA topoisomerases have been molecular targets for anticancer agents since their discovery in 1971 [63]. Topoisomerases regulate DNA winding and play essential functions in DNA replication and transcription [59][64]. Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) creates transient single-DNA nicks, while topoisomerases 2 (Top2α and Top2β) produce transient double-stranded DNA breaks. Both nuclear Top1 and Top2 are important targets for cancer chemotherapy, and Top inhibitors are used in therapeutic protocols [65][66][67]. Top inhibitors are classified into two groups: poisons and catalytic inhibitors. Top poisons (or interfacial poisons) stabilize the reversible cleavage complex formed between Top and DNA and form a ternary complex. Top2 catalytic inhibitors can prevent DNA strands cleavage through inhibition of the ATPase activity (novobiocin, merbarone), by impeding ATP hydrolysis to block Top dissociation from the DNA (ICRF-193), or by DNA intercalation at the Top fixation site (aclarubicinet) see [68]. In all cases, inhibitors convert the indispensable nuclear Top enzyme into a killing tool.

Top inhibitors’ activity increases upon complexation with copper ion. Top1, Top2, or Top1/2 inhibitors synthesized in the form of copper complexes (CuC) are mostly mononuclear Cu(II) complexes associated with a variety of ligands (Table 1). Different strategies are currently proposed to design and develop Top inhibitory agents based on ligands’ properties [69]. If both Top1 and Top2 inhibitors CuC primarily target DNA by a direct interaction through intercalation or cleavage, their antiproliferative activity is reinforced by ROS production and other molecular targets (Table 1) [25][52].

Table 1. Copper complexes inhibitors of topoisomerases: targeted top isoforms, cancer cell lines responses, and molecular mechanisms are summarized. * Tests were realized in vitro with human Top1 or Top2α/β unless specified. IC50: half-maximal inhibitory concentration. EC50: half-maximal effective concentration. GI50: half-average of growth inhibition.

|

Ligand Class of Cu-C |

Compound Number |

Targeted Top(s) |

Inhibition of DNA Relaxation Total (µM) (minimal (µM)) |

Inhibition Mecanism |

Cancer Cell Lines |

IC50 (µM) |

Cell Cycle Arrest |

Cell Death Type |

Other Specificity |

Reference Number |

|

Oxindolimine |

1 |

Top1

|

50 (25) |

Fixation in the DNA |

Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Promonocytic U937 |

|

G2/M arrest |

Apoptosis |

ROS induction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Hydrazone with triphenylphosphonium |

2 |

Top1

|

40

|

DNA Binding |

Lung A549 |

4.2 ± 0.8 |

|

|

|

[74] |

|

Enzyme complex formation |

Prostatic PC-3 |

3.2 ± 0.2 |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Plumbagin |

3 |

Top1 |

1.56 |

DNA intercalation |

Breast MCF-7 |

3.2 ± 1.1 |

|

|

|

[75] |

|

|

|

|

Colon HCT116 |

5.9 ± 1.4 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Hepatoma BEL7404 |

12.9 ± 3.6 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Hepatoma HepG2 |

9.0 ± 0.7 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Kidney 786-O |

2.5 ± 0.9 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Lung NCI-H460 |

2.0 ± 1.2 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Nasopharyngeal cancer CNE2 |

11.8 ± 5.9 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Phenanthroline with amino acids |

4 |

Top1 |

50 |

DNA intercalation |

Nasopharyngeal cancer HK1 |

2.2 - 5.2 |

|

Apoptosis |

|

[76] |

|

|

(10) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Pyrophosphate |

5 |

Top1 |

500 |

DNA interaction |

Ovarian A2780/AD |

0.64 ± 0.12 |

|

|

|

[77] |

|

Heterobimetallic Cu(II)-Sn2(IV) phenanthroline

|

6 |

Top1 |

20 |

DNA intercalation |

Breast Zr-75–1 |

|

|

|

|

[78] |

|

|

|

cleavage |

Cervix SiHa |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Colon HCT15, SW620 |

< 10 (GI50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Kidney 786-O, A498 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Lung Hop-62, A569 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Pancreatic MIA PaCa-2 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y |

2 – 8 |

|

Apoptosis |

|

[79] |

||

|

Analogs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[80] |

|

Tridentate chiral Schiff base |

7, 8 |

Top1 |

25 |

DNA binding |

Hepatoma HuH7 |

25 |

|

|

ROS |

|

|

|

(15) |

major groove |

Hepatoma HepG2 |

6.2 ± 10 |

|

|

Cytokine TGFb |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

mRNA upregulation |

|

||

|

Salicylidene |

9 |

Top1 |

(E. coli)* |

DNA binding |

Prostatic PC-3 |

7.3 ± 0.2 |

|

|

antimetastasis |

[83] |

|

|

|

DNA cleavage |

Breast MCF7 |

51.1 ± 1.6 |

|

|

|

[84] |

||

|

|

|

|

Colon HT29 |

16.6 ± 0.6 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Hepatoma HepG2 |

2.3 ± 0.1 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Lung A549 |

16.8 ± 1.0 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Ovary A2780 |

14.6 ± 0.2 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Prostatic LNCaP |

25.4 ± 0.8 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Chalcone-derived Thiosemicarbazone |

10 |

Top1 |

3 |

DNA binding |

Breast MCF-7 |

0.16 ± 0.06 |

|

|

|

[85] |

|

|

(0.75) |

DNA cleavage |

Leukemia THP-1 |

0.20 ± 0.06 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Religation inhibition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Pyridyl-substituted tetrazolopyrimidie |

11 |

Top1 |

(Molecular docking) * |

DNA binding |

Cervix HeLa |

0.565 ± 0.01 |

|

Apoptosis |

CDK receptor |

[86] |

|

|

groove mode |

Colon HCT-15 |

0.358 |

|

|

binding |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Lung A549 |

0.733 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Tetrazolopyrimidine Diimine

|

|

Top1 |

102 ± 1.1 |

DNA binding |

Cervical HeLa |

0.620 ± 0.0013 |

|

Apoptosis |

vEGF receptor |

[87] |

|

|

|

groove mode |

Colon HCT-15 |

0.540 ± 0.00015 |

|

|

binding |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Lung A549 |

0.120 ± 0.002 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Piperazine |

12 |

Top1 |

12.5 |

DNA binding |

|

|

|

|

SOD mimic |

[88] |

|

|

(5) |

minor groove |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Elesclomol |

13 |

Top1 |

50 |

Poison |

Erythroleukemic K562 |

0.0075 |

|

Apoptosis |

Copper chelator |

[89] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Necrosis |

Not a substrat for |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oxidative stress |

ABC transporters |

|

||

|

Cu(SBCM)2 |

14 |

Top1 |

*(Molecular |

DNA intercalation |

Breast MCF7 |

27 |

G2/M arrest |

Apoptosis |

p53 increase |

[90] |

|

|

docking) |

DNA binding |

Breast MDA-MB-231 |

18.7 ±3.1 |

|

|

No ROS |

[91] |

||

|

TSC and TSC CuC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pyridine-TSC |

15 |

Top2α |

50 |

|

Breast MDA-MB-231 |

1.01 |

|

|

|

[98] |

|

(10) |

|

Breast MCF7 |

0.0558 |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

50 |

ATP hydrolysis inhibition |

|

|

|

|

|

[99] |

|||

|

Top2β |

(5) |

ATP hydrolysis inhibition |

|

|

|

|

|

[100] |

||

|

Piperazine-TSC |

16 |

Top2α |

0.9 ± 0.7 |

Potentially catalytic |

Breast MCF7 |

4.7 ± 0.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Breast SK-BR-3 |

1.3 ± 0.3 |

|

|

|

[99] |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

Thiazole-TSC |

17 |

Top2α |

4 |

|

Breast MDA-MB-231 |

1.41 (EC50) |

|

|

|

[103] |

|

|

(2) |

|

Breast MCF7 |

0.13 (EC50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

17–18 |

Top2α |

25 |

ATP hydrolysis inhibition |

Breast |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(10) |

+ Poison |

HCC 70, HCC 1395, |

1 to 20 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

HCC 1500, and HCC 1806 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Colon |

0.83 to 41.2 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Caco-2, HCT-116 and HT-29 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

L- and D-Proline-TSC |

19 |

Top2α |

300 |

|

Ovarian carcinoma CH1 |

113 ± 16 |

|

|

|

[106] |

|

Quinoline-TSC |

20 |

Top2α |

0.48 |

Potentially catalytic |

Lymphoma U937 |

0.48-16.2 |

|

|

|

[107] |

|

Naphthoquinone-TSC |

21 |

Top2α |

1 mM |

|

Breast MCF7 |

3.98 ± 1.01 |

|

No apoptosis |

|

[108] |

|

Bis-TSC |

22 |

Top2α |

100 |

Poison |

Breast MDA-MB-231 |

1.45 ± 0.07 |

G2/M arrest |

Apoptosis |

DNA synthesis |

[109] |

|

|

(5) |

|

Colon HCT116 |

1.23 ± 0.27 |

|

|

inhibition |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Keratinocyte HaCaT |

0.65 ± 0.07 |

|

|

No ROS |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Colon HCT116 |

Delayed mice xenograft |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Carbohydrazone |

23 |

Top2α |

250 |

DNA binding |

Breast MCF7 |

9.916 |

|

Apoptosis |

|

[110] |

|

|

(25) |

major groove |

Breast MDA-MB-231 |

7.557 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Breast HCC 1937 |

3.278 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Breast MX1 |

4.534 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Breast MDA-MB-436 |

5.249 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Breast MX-1 |

Reducted mice xenograft (83%) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Chromone |

24 |

Top2α |

25 |

DNA binding |

Breast MCF7 |

18.6 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

[111] |

|

|

(15) |

major groove |

Breast Zr-75-1 |

25.2 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Colon HT29 |

>80 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Cervix SiHa |

34.6 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Kidney A498 |

73.3 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Lung A549 |

31.7 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Ovary A2780 |

17.4 (GI 50) |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Quinolinone Shiff Base |

25 |

Top2α |

9 |

No intercalation |

Hepatic HepG2 |

17.9 ± 3.8 |

|

|

DNA synthesis |

[112] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

inhibition |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Slight substrate |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

for ABC transporter |

|

||

|

Bis-pyrazolyl Carboxylate |

26 |

Dual Top1/Top2 |

(Molecular docking) * |

ATP entry (potentially) |

Hepatic HepG2 |

3.3 ± 0.02 |

|

Apoptosis |

DNA replication |

[113] |

|

DNA religation inhibition (potentially) |

|

|

|

|

ROS |

|

2.1. CuC Top1 Inhibitors

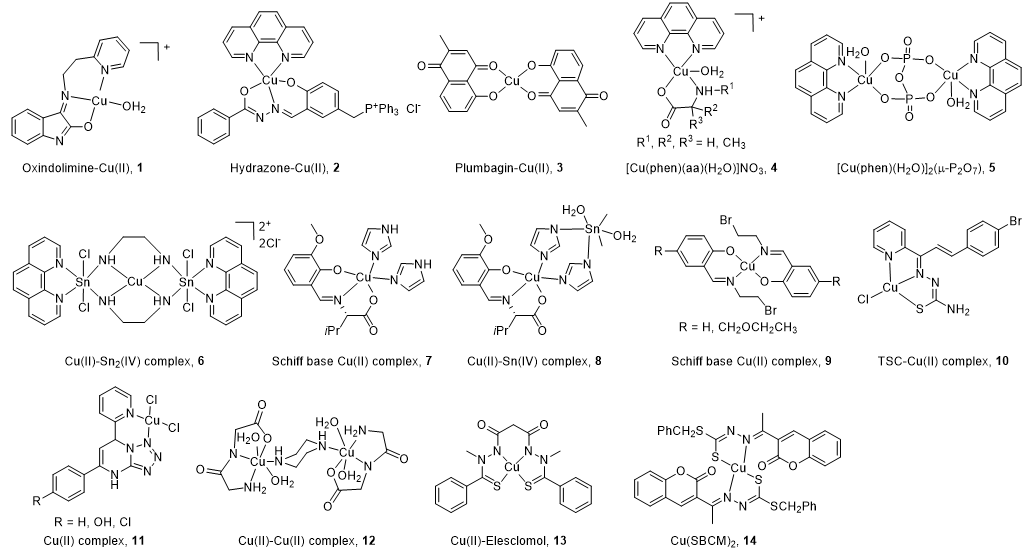

All the structures of CuC Top1 inhibitors are reported in Figure 2 and the main characteristics in Table 1. Oxindolimine-Cu(II) Top1 inhibitors such as 1 are planar copper compounds [70] that do not permit enzyme-DNA complex formation [71][72][73]. Besides, they produce ROS [70]. Cu(II) derivative complexes of the hydrazone ligand with triphenylphosphonium moiety 2 can bind DNA and the Top enzyme [74] Plumbagin-Cu(II) 3 selectively intercalates into DNA [75]. The latter compound [75] and the phenanthroline-Cu(II) complexes modulated by amino acids 4 [76] can induce cancer cell apoptosis via mitochondrial signaling. Copper pyrophosphate-bridged binuclear complex 5 interacts with DNA, and based on the redox chemistry of copper, induces significant oxidative stress in cancer cell lines [77].

Figure 2. Structure of Cu(II) complexes as Top1 inhibitors.

In the heterobimetallic Cu(II)-Sn2(IV) (copper/tin) complex 6, the planar phenanthroline heterocyclic ring approaches the Top−DNA complex Cu(II)-Sn2(IV) toward the DNA cleavage site and forms a stable complex with Top1 [78][79]. Other Cu(II)-Sn2(IV) analogs induce apoptosis [80]. Chiral monometallic or heterobimetallic complexes 7 and 8 with tridentate chiral Schiff base–ONO-ligand are DNA groove binders and produce ROS [81][82].

Salicylidene-Cu(II) derivative 9 of 2-[2-bromoethyliminomethyl] phenol [83][84] is a bifunctional drug that inhibits both cancer cell growth and metastasis.

Chalcone-derived thiosemicarbazone (TSC) Cu(II) complex 10 prevents the DNA cleavage step of the Top1 catalytic cycle and DNA relegation [85].

Tetrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-based Cu(II) complexes 11 have a square planar geometry, and despite their high capability to inhibit Top1, interact with CDK for 11 [86] and VEGF receptors for an analog of 11 [87]. Binuclear Cu(II) dipeptide piperazine-bridged complex 12 recognizes specific sequences in the DNA, oxidatively cleaves DNA, and displays superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity [88].

Derived from elesclomol (in clinical trials: phase 3 against melanoma and randomized phases 2 and 3 for the treatment of a variety of other cancers), the elesclomol-Cu(II) complex 13 inhibits Top1 and induces apoptosis in cancer cells [89].

As recently studied, Cu(II)(SBCM)2 14 derived from S-benzyldithiocarbazate and 3-acetylcoumarin intercalates into DNA, induces ROS production, and has an antiproliferative activity in breast cancer lines [90][91].

2.2. CuC Top2α Inhibitors

Due to its cell cycle phase dependence and its high expression in proliferating cells, the Top2α isoform is primarily targeted by copper complexes (CuC), whereas Top2β remains unchanged during the course of the cell cycle [66]. Another reason to limit the clinical application of Top2β inhibitors is the strong unwanted side effects produced (secondary leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and cardiac toxicity [92][93]).

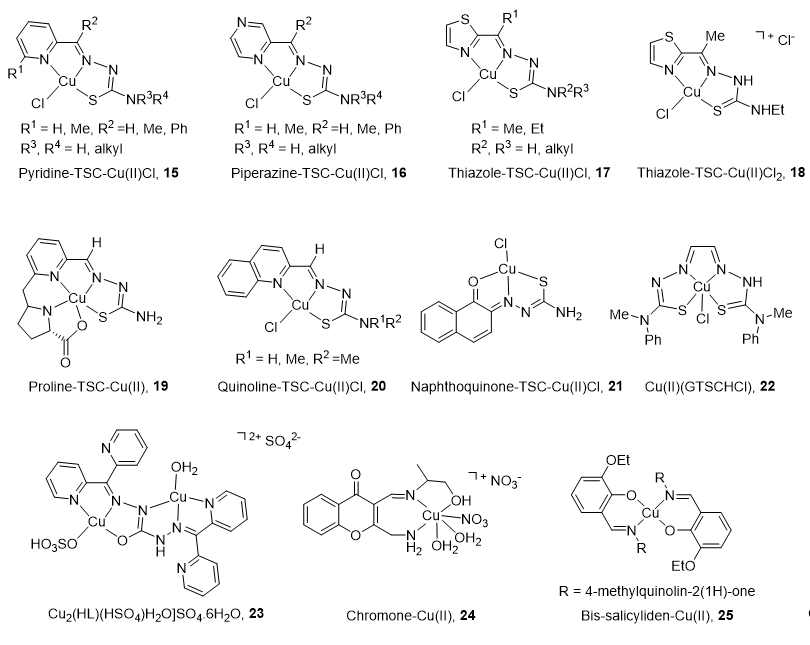

The main characteristics and structures of CuC Top2 inhibitors are reported in Figure 3 and Table 1. Several α-(N)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazone (TSC) CuC [94][95] present a greater inhibitory effect on Top2α than corresponding TSC ligands alone [96][97] due to a square planar structure around the Cu(II) ion. A specific subset of pyridine-TSC CuC 15 inhibits Top2α [98] acting as ATP hydrolysis inhibitors in a non-competitive mode [94][99][100]. Another pyridine-TSC CuC inhibits Top2β [100]. Molecular modeling supports the binding of the complexes near but outside the ATP binding pocket in communication with the DNA cleavage/ligation site of Top2. Piperazine-TSCs based CuC 16 inhibit Top2α [101][102] by a strong interaction with the ATP-binding pocket residues [99] without ROS production [102]. Thiazole-TSC CuC 17 and 18 are Top2α catalytic inhibitors [103][104] or poisons [105]. The highly water-soluble proline-TSC CuC series 19 inhibit Top2α and cell proliferation [106]. Quinoline-TSC CuC 20 interact with the DNA phosphate group preventing relegation. The presence of two methyl groups on the terminal nitrogen is responsible for high activity and confers a cationic nature responsible for easier passive access into the cell [107].

Figure 3. Structure of Cu(II) complexes as Top2 inhibitors.

Non-heterocycle naphthoquinone-TSC CuC 21 [108] and bis-TSC CuC 22 [109] are Top2α inhibitors acting as poisons [109]; they induce apoptosis in various human cancer cell lines and delay colorectal growth of carcinoma xenografts in mice [109]. Carbohydrazone CuC 23 [110] is a Top2α inhibitor that binds DNA, induces apoptosis, and reduces mice xenograft (83% after a treatment of 2 mg/kg). Chiral chromone Cu(II)/Zn(II) 24 [111] revealed catalytic inhibition of Top2α with DNA binding in the major groove. Quinolinone CuC 25 [112] inhibit Top2α and DNA synthesis without DNA intercalation and are only minimized PGP (P-glycoprotein efflux transporter) substrates.

2.3. CuC Dual Top1/Top2α Inhibitors

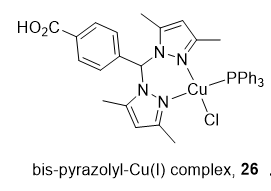

Heteroleptic Cu(I) complexes of the bis-pyrazolyl carboxylate ligand with auxiliary phosphine 26 (Figure 4) may inhibit Top1 by blocking the relegation step and inhibit Top2α by preventing ATP hydrolysis, as proposed by molecular docking analysis. They also perturb DNA replication, generate ROS, and induce apoptosis [113].

Figure 4. Structure of Cu(I) complex as a Top1/2α dual inhibitor.

References

- Rosenberg, ; VanCamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum compounds: A new class of potent antitumour agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386.

- Alderden, A.; Hall, M.D.; Hambley, T.W. The discovery and development of cisplatin. J. Chem. Educ. 2006, 83, 728–734.

- Dilruba, S.; Kalayda, G.V. Platinum-based drugs: Past, present and Cancer Chemother. Pharm. 2016, 77, 1103–1124.

- Bergamo, A.; Dyson, P.J.; Sava, G. The mechanism of tumour cell death by metal-based anticancer drugs is not only a matter of DNA Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 360, 17–33.

- Dasari, ; Tchounwou, P.B. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharm. 2014, 740, 364–378.

- Manohar, ; Leung, N. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A review of the literature. J. Nephrol. 2018, 31, 15–25.

- Herradón, ; González, C.; Uranga, J.A.; Abalo, R.; Martín, M.I.; López-Miranda, V. characterization of cardiovascular alterations induced by different chronic cisplatin treatments. Front. Pharm. 2017, 8, 196–211.

- Shen, W.; Pouliot, L.M.; Hall, M.D.; Gottesman, M.M. Cisplatin resistance: A cellular self-defense mechanism resulting from multiple epigenetic and genetic changes. Pharm. Rev. 2012, 64, 706–721.

- Chen, H.; Chang, J.Y. New insights into mechanisms of cisplatin resistance: From tumor cell to microenvironment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4136–4157.

- Obrist, ; Michels, J.; Durand, S.; Chery, A.; Pol, J.; Levesque, S.; Joseph, A.; Astesana, V.; Pietrocola, F.; Wu, G.S.; et al. Metabolic vulnerability of cisplatin-resistant cancers. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e98597.

- Amable, Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharm. Res. 2016, 106, 27–36.

- Galluzzi, ; Senovilla, L.; Vitale, I.; Michels, J.; Martins, I.; Kepp, O.; Castedo, M.; Kroemer, G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene 2012, 31, 1869–1883.

- Housman, ; Byler, S.; Heerboth, S.; Lapinska, K.; Longacre, M.; Snyder, N.; Sarkar, S. Drug resistance in cancer: An overview. Cancers 2014, 6, 1769–1792.

- Martinho, ; Santos, T.; Florindo, H.F.; Silva, L.C. Cisplatin-membrane interactions and their influence on platinum complexes activity and toxicity. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1898–1913.

- Zeng, ; Gupta, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, E.; Ji, L.; Chao, H.; Chen, Z.-S. The development of anticancer ruthenium(ii) complexes: From single molecule compounds to nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 5771–5804.

- Zhang, ; Sadler, P. J. Advances in the design of organometallic anticancer complexes. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 839, 5–14.

- Jaouen, ; Vessières, A.; Top, S. Ferrocifen type anti cancer drugs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8802–8817.

- Gianferrara, ; Bratsos, I.; Alessio, E. A categorization of metal anticancer compounds based on their mode of action. Dalton Trans. 2009, 37, 7588–7598.

- Hartinger, G.; Dyson, P.J. Bioorganometallic chemistry from teaching paradigms to medicinal applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 391–401.

- Wambang, ; Schifano-Faux, N.; Martoriati, A.; Henry, N.; Baldeyrou, B.; Bal-Mahieu, C.; Bousquet, T.; Pellegrini, S.; Meignan, S.; Cailliau, K.; et al. Synthesis, structure, and antiproliferative activity of ruthenium(ii) arene complexes of indenoisoquinoline derivatives. Organometallics 2016, 35, 2868–2872.

- Wambang, N.; Schifano-Faux, N.; Aillerie, A.; Baldeyrou, B.; Jacquet, C.; Bal-Mahieu, C.; Bousquet, T.; Pellegrini, S.; Ndifon, T.P.; Meignan, S.; Goossens, J.F.; Lansiaux, A.; Pelinski, L. Synthesis and biological activity of ferrocenyl indeno[1 ,2-c]isoquinolines as topoisomerase II Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 651–660.

- Komeda, ; Casini, A. Next-generation anticancer metallodrug. Cur. Top. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 219–235.

- Mejía, ; Ortega-Rosales, S.; Ruiz-Azuara, L. Mechanism of action of anticancer metallodrugs. In Biomedical Applications of Metals; Rai, M., Ingle, A., Medici, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10, pp. 213–234.

- Denoyer, ; Clatworthy, S.A.S.; Cater, M.A. Copper complexes in cancer therapy. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2018, 18, 469–506.

- Santini, ; Pellei, M.; Gandin, V.; Porchia, M.; Tisato, F.; Marzano, C. Advances in copper complexes as anticancer agents. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 815–862.

- Jungwirth, ; Kowol, C.R.; Keppler, B.K.; Hartinger, C.G.; Berger, W.; Heffeter, P. Anticancer activity of metal complexes: Involvement of redox processes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1085–1127.

- Tardito, ; Marchiò, L. Copper compounds in anticancer strategies. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1325–1348.

- Marzano, ; Pellei, M.; Tisato, F.; Santini, C. Copper complexes as anticancer agents. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 185–211.

- Kellett, ; Molphy, Z.; McKee, V.; Slator, C. Recent advances in anticancer copper compounds. In Metal-based Anticancer Agents; Vessieres, I.A., Meier-Menches, S.M., Casini, A., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry, RSC Metallobiology: London, UK 2019; Volume 14, pp. 91–119.

- Hordyjewska, ; Popiołek, L.; Kocot, J. The many ‘‘faces’’ of copper in medicine and treatment. Biometals 2014, 27, 611–621.

- Urso, ; Maffia, M. Behind the link between copper and angiogenesis: Established mechanisms and an overview on the role of vascular copper transport systems. J. Vasc. Res. 2015, 52, 172–196.

- Lowndes, A.; Harris, A.L. The role of copper in tumour angiogenesis. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2005, 10, 299–310.

- Hu, F. Copper stimulates proliferation of human endothelial cells under culture. J. Cell. Biochem. 1998, 69, 326–335.

- Yoshida, ; Ikeda, Y.; Nakazawa, S. Quantitative analysis of copper, zinc and copper/zinc ratio in selected human brain tumors. J. Neurooncol. 1993, 16, 109–115.

- Geraki, ; Farquharson, M.J.; Bradley, D.A. Concentrations of Fe, Cu and Zn in breast tissue: A synchrotron XRF study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2002, 47, 2327–2339.

- Nayak, B.; Bhat, V.R.; Upadhyay, D.; Udupa, S.L. Copper and ceruloplasmin status in serum of prostate and colon cancer patients. Indian J. Physiol Pharm. 2003, 47, 108–110.

- Díez, ; Arroyo, M.; Cerdàn, F.J.; Muñoz, M.; Martin, M.A.; Balibrea, J.L. Serum and tissue trace metal levels in lung cancer. Oncology 1989, 46, 230–234.

- Kaiafa, D.; Saouli, Z.; Diamantidis, M.D.; Kontoninas, Z.; Voulgaridou, V.; Raptaki, M.; Arampatzi, S.; Chatzidimitriou, M.; Perifanis, V. Copper levels in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 23, 738−741.

- Baldari, ; Di Rocco, G.; Toietta, G. Current biomedical use of copper chelation therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1069–1089.

- Denoyer, ; Masaldan, S.; La Fontaine, S.; Cater, M.A. Targeting copper in cancer therapy: ‘Copper That Cancer’. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1459–1476.

- Cater, M.A.; Pearson, H.B.; Wolyniec, K.; Klaver, P.; Bilandzic, M.; Paterson, B.M.; Bush, A.I.; Humbert, P.O.; La Fontaine, S.; Donnelly, P.S.; Haupt, Y. Increasing intracellular bioavailable copper selectively targets prostate cancer ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 1621–1631.

- Cater, A.; Haupt, Y. Clioquinol induces cytoplasmic clearance of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP): Therapeutic indication for prostate cancer. Biochem. J. 2011, 436, 481–491.

- Cheriyan, T.; Wang, Y.; Muthu, M.; Jamal, S.; Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Polin, L.A.; Tarca, A.L.; Pass, H.I.; Dou, Q.P.; et al. Disulfiram suppresses growth of the malignant pleural mesothelioma cells in part by inducing apoptosis. Plos ONE 2014, 9, e93711.

- Duan, ; Shen, H.; Zhao, G.; Yang, R.; Cai, X.; Zhang, L.; Jin, C.; Huang, Y. Inhibitory effect of Disulfiram/copper complex on non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 1010–1016.

- Jivan, R.; Damelin, L.H.; Birkhead, M.; Rousseau, A.L.; Veale, R.B.; Mavri-Damelin, D. Disulfiram/copper-disulfiram damages multiple protein degradation and turnover pathways and cytotoxicity is enhanced by metformin in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 2334–2343.

- Safi, R.; Nelson, E.R.; Chitneni, S.K.; Franz, K.J.; George, D.J.; Zalutsky, M.R.; McDonnell, D.P. Copper signaling axis as a target for prostate cancer Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 5819–5831.

- Wang, ; Jiao, P.; Qi, M.; Frezza, M.; Dou, Q.P.; Yan, B. Turning tumor-promoting copper into an anti-cancer weapon via high-throughput chemistry. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 2685–2698.

- Zhang, ; Wang, H.; Yan, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C. Novel copper complexes as potential proteasome inhibitors for cancer treatment. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 15, 3–11.

- Krasnovskaya, ; Naumov, A.; Guk, D.; Gorelkin, P.; Erofeev, A.; Beloglazkina, E.; Majouga, A. Copper Coordination Compounds as Biologically Active Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3965–4002.

- Brissos, F.; Caubet, A.; Gamez, P. Possible DNA-interacting pathways for metal-based compounds exemplified with copper coordination compounds. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 16, 2633–2645.

- Kagawa, F.; Geierstanger, B.H.; Wang, A.H.J.; Ho, P.S. Covalent modification of guanine bases in double-stranded DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 20175–20184.

- Ceramella, J.; Mariconda, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Saturnino, C.; Barbarossa, A.; Caruso, A.; Rosano, C.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Longo, P. From coins to cancer therapy: Gold, silver and copper complexes targeting human Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 126905–126916.

- Shobha Devi, ; Thulasiram, B.; Aerva, R.R.; Nagababu, P. Recent advances in copper intercalators as anticancer agents. J. Fluoresc. 2018, 28, 1195–1205.

- Liang, ; Wu, Q.; Luan, S.; Yin, Z.; He, C.; Yin, L.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, L.; Song, X.; et al. A comprehensive review of topoisomerase inhibitors as anticancer agents in the past decade. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 171, 129–168.

- Cuya, M.; Bjornsti, M.A.; van Waardenburg, R.C.A.M. DNA topoisomerase-targeting chemotherapeutics: what’s new? Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2017, 80, 1–14.

- Thomas, ; Pommier, Y. Targeting topoisomerase I in the era of precision medicine. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 6581–6589.

- Pommier, Drugging topoisomerases: Lessons and challenges. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 82–95.

- Bjornsti, M.A.; Kaufmann, S.H. (2019). Topoisomerases and cancer chemotherapy: Recent advances and unanswered F1000 Res. 2019, 8, doi:10.12688/f1000research.20201.1

- Pommier, ; Sun, Y.; Huang, S.N.; Nitiss, J.L. Roles of eukaryotic topoisomerases in transcription, replication and genomic stability. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 17, 703–721.

- Pommier, Y.; Leo, E.; Zhang, H.; Marchand, C. DNA topoisomerases and their poisoning by anticancer and antibacterial Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 421–433.

- Hevener, ; Verstak, T.A.; Lutat, K.E.; Riggsbee, D.L.; Mooney, J.W. Recent developments in topoisomerase-targeted cancer chemotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2018, 8, 844–861.

- Xu, ; Her, C. Inhibition of Topoisomerase (DNA) I (TOP1): DNA damage repair and anticancer therapy. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 1652–1670.

- Wang, C. Interaction between DNA and an Escherichia coli protein omega. J. Mol. Biol. 1971, 55, 523–533.

- Madabhushi, The roles of DNA topoisomerase IIβ in transcription. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1917–1932.

- Sakasai, ; Iwabuchi, K. The distinctive cellular responses to DNA strand breaks caused by a DNA topoisomerase I poison in conjunction with DNA replication and RNA transcription. Genes Genet. Syst. 2016, 90, 187–194.

- Lee, J.H.; Berger, J.M. Cell cycle-dependent control and roles of DNA topoisomerase Genes 2019, 10, 859–877.

- Li, ; Liu, Y. Topoisomerase I in human disease pathogenesis and treatments. Genom. Proteom. Bioinfo. 2016, 14, 166–171.

- Larsen, K.; Escargueil, A.E.; Skladanowski, A. Catalytic topoisomerase II inhibitors in cancer therapy. Pharm. 2003, 99, 167–181.

- Hu, W.; Huang, X.S.; Wu, J.F.; Yang, L.; Zheng, Y.T.; Shen, Y.M.; Li, Z.Y.; Li, X. Discovery of novel topoisomerase II inhibitors by medicinal chemistry J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 8947–8980.

- Castelli, ; Goncalves, M.B.; Katkar, P.; Stuchi, G.C.; Couto, R.A.A.; Petrilli, H.M.; da Costa Ferreira, A.M. Comparative studies of oxindolimine-metal complexes as inhibitors of human DNA topoisomerase IB. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 186, 85–94.

- Katkar, P.; Coletta, A.; Castelli, S.; Sabino, G.L.; Alves Couto, R.A.; da Costa Ferreira, A.M.; Desideri, A. Effect of oxindolimine copper(ii) and zinc(ii) complexes on human topoisomerase I activity. Metallomics 2014, 6, 117–125.

- Cerchiaro, G.; Aquilano, K.; Filomeni, G.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Ferreira, A.M. Isatin-Schiff base copper(II) complexes and their influence on cellular J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005, 99, 1433–1440.

- Filomeni, G.; Cerchiaro, G.; Da Costa Ferreira, A.M.; De Martino, A.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Pro-apoptotic activity of novel Isatin-Schiff base copper(II) complexes depends on oxidative stress induction and organelle-selective J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 12010–12021.

- Chew, T.; Lo, K.M.; Lee, S.K.; Heng, M.P.; Teoh, W.Y.; Sim, K.S.; Tan, K.W. Copper complexes with phosphonium containing hydrazone ligand: Topoisomerase inhibition and cytotoxicity study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 397–407.

- Chen, F.; Tan, M.X.; Liu, L.M.; Liu, Y.C.; Wang, H.S.; Yang, B.; Peng, Y.; Liu, H.G.; Liang, H.; Orvig, C. Cytotoxicity of the traditional chinese medicine (tcm) plumbagin in its copper chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2009, 48, 10824–10833.

- Seng, H.L.; Wang, W.S.; Kong, S.M.; Alan Ong, H.K.; Win,YF; Raja Abd Rahman, R.N.Z.; Chikira, M.; Leong, W.K.; Ahmad, M.; Khoo, A.S.B.; Ng, C.H. Biological and cytoselective anticancer properties of copper(II)-polypyridyl complexes modulated by auxiliary methylated glycine BioMetals 2012, 25, 1061–1081.

- Ikotun, F.; Higbee, E.M.; Ouellette, W.; Doyle, R.P. Pyrophosphate-bridged complexes with picomolar toxicity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 1254–1264.

- Tabassum, ; Afzal, M.; Arjmand, F. Synthesis of heterobimetallic complexes: In vitro DNA binding, cleavage and antimicrobial studies. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2012, 114, 108–118.

- Chauhan, ; Banerjee, K.; Arjmand, F. DNA binding studies of novel copper(ii) complexes containing l-tryptophan as chiral auxiliary: in vitro antitumor activity of cu−sn2 complex in human neuroblastoma cells. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 3072–3082.

- Afzal, ; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Usman, M.; Tabassum, S. Carbohydrate-based heteronuclear complexes as topoisomerase Iα inhibitor: Approach toward anticancer chemotherapeutics. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 1494–1510.

- Tabassum, ; Ahmad, A.; Khan, R.A.; Hussain, Z.; Srivastav, S.; Srikrishna, S.; Arjmand, F. Chiral heterobimetallic complexes targeting human DNA-topoisomerase Iα. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 16749–16761.

- Tabassum, ; Asim, A.; Khan, R.A.; Arjmand, F.; Rajakumar, D.; Balaji, P.; Akbarsha, A.M. A multifunctional molecular entity CuII–SnIV heterobimetallic complex as a potential cancer chemotherapeutic agent: DNA binding/cleavage, SOD mimetic, topoisomerase Ia inhibitory and in vitrocytotoxic activities. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 47439–47450.

- Lee, K.; Tan, K.W.; Ng, S.W. Zinc, copper and nickel derivatives of 2-[2-bromoethyliminomethyl]phenol as topoisomerase inhibitors exhibiting anti-proliferative and antimetastatic properties. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 60280–60292.

- Lee, K.; Tan, K.W.; Ng, S.W. Topoisomerase I inhibition and DNA cleavage by zinc, copper, and nickel derivatives of 2-[2-bromoethyliminomethyl]-4-[ethoxymethyl]phenol complexes exhibiting anti-proliferation and anti-metastasis activity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 159, 14–21.

- Vutey, ; Castelli, S.; D’Annessa, I.; Sâmia, L.B.; Souza-Fagundes, E.M.; Beraldo, H.; Desideri, A. Human topoisomerase IB is a target of a thiosemicarbazone copper(II) complex. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 606, 34–40.

- Haleel, K.; Mahendiran, D.; Rafi, U.M.; Veena, V.; Shobana, S.; Rahiman, A.K. Tetrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine-based metal(II) complexes as therapeutic agents: DNA interaction, targeting topoisomerase I and cyclin-dependent kinase studies. Inorg. Nano. Met. Chem. 2019, 48, 569–582.

- Haleel, A.K.; Mahendiran, D.; Veena, V.; Sakthivel, N.; Rahiman, A.K. Antioxidant, DNA interaction, VEGFR2 kinase, topoisomerase I and in vitro cytotoxic activities of heteroleptic copper(II) complexes of tetrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines and Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 68, 366–382.

- Tabassum, ; Al-Asbahy, W.M.; Afzal, M.; Arjmand, F.; Bagchi, V. Molecular drug design, synthesis and structure elucidation of a new specific target peptide based metallo drug for cancer chemotherapy as topoisomerase I inhibitor. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 4955–4964.

- Hasinoff, B.; Wu, X.; Yadav, A.A.; Patel, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.S.; Chen, Z.S.; Yalowich, J.C. Cellular mechanisms of the cytotoxicity of the anticancer drug elesclomol and its complex with Cu(II). Biochem. Pharm. 2015, 93, 266–276.

- Foo, B.; Ng, L.S.; Lim, J.H.; Tan, P.X.; Lor, Y.Z.; Loo, J.S.; Low, M.L.; Chan, L.C.; Beh, C.Y.; Leong, S.W.; et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by copper complex Cu(SBCM)2 towards oestrogen-receptor positive MCF-7 breast cancer cells. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18359–18370.

- Foo, J.B.; Low, M.L.L.; Lim, J.H.; Lor, Y.Z.; Abidin, R.Z.; Dam, V.E.; Rahman, N.A.; Beh, C.Y.; Chan, L.C.; How, C.W.; Tor, C.W.; et al. Copper complex derived fromS-benzyldithiocarbazate and 3-acetylcoumarin induced apoptosis in breast cancer Biometals 2018, 4, 505–515.

- Yeh, T.H.; Ewer, M.; Moslehi, J.; Dlugosz-Danecka, M.; Banchs, J.; Chang, H.M.; Minotti, G. Mechanisms and clinical course of cardiovascular toxicity of cancer treatment I. Oncology. Semin. Oncol. 2019, 46, 397–402.

- Pendleton, ; Lindsey, R.H., Jr, Felix, C.A.; Grimwade, D.; Osheroff, N. Topoisomerase II and leukemia. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1310, 98–110.

- West, X.; Thientanavanich, I.; Liberta, A.E. Copper(II) complexes of 6-methyl-2-acetylpyridine N(4)-substituted thiosemicarbazones. Trans. Met. Chem. 1995, 20, 303–308.

- Miller, C.; Bastow, K.F.; Stineman, C.N.; Vance, J.R.; Song, S.C.; West, D.X.; Hall, I.H. The Cytotoxicity of 2-Formyl and 2-Acetyl-(6-picolyl)-4 N-Substituted Thiosemicarbazones and Their Copper(II) Complexes. Arch. Pharm. Pharm. Med. Chem. 1998, 331, 121–127.

- Khan, ; Rahmad, R.; Joshi, S.; Khan, A.R. Anticancer potential of metal thiosemicarbazone complexes: A review. Der Chem. Sin. 2015, 6, 1–11.

- Huang, ; Chen, Q.; Xin, K.; Meng, L.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; et al. A series of α-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones inhibit topoisomerase IIα catalytic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3048–3064.

- Conner, D.; Medawala, W.; Stephens, M.T.; Morris, W.H.; Deweese, J.E.; Kent, P.L.; Rice, J.J.; Jiang, X.; Lisic, E.C. Cu(II) benzoylpyridine thiosemicarbazone complexes: Inhibition of human topoisomerase IIα and activity against breast cancer cells. Open J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 6, 146–154.

- Wilson, T.; Jiang, X.; McGill, B.C.; Lisic, E.C.; Deweese, J.E. Examination of the impact of copper(ii) α-(n)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazone complexes on dna topoisomerase IIα. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 649–658.

- Keck, J.M.; Conner, J.D.; Wilson, J.T.; Jiang, X.; Lisic, E.C.; Deweese, J.E. Clarifying the mechanism of copper(II) α-(N)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazone complexes on DNA topoisomerase IIα and IIβ. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 2135–2143.

- Miller, C.; Stineman, C.N.; Vance, J.R.; West, D.X. Multiple Mechanisms for Cytotoxicity Induced by Copper(II) Complexes of 2-Acetylpyrazine-N-substituted Thiosemicarbazones. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 1999, 13, 9–19.

- Zeglis, M.; Divilov, V.; Lewis, J.S. Role of metalation in the topoisomerase IIα inhibition and antiproliferation activity of a series of α-heterocyclic-N4-substituted thiosemicarbazones and their Cu(II) complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 2391–2398.

- Lisic, E.C.; Rand, V.G.; Ngo, L.; Kent, P.; Rice, J.; Gerlach, D.; Papish, E.T.; Jiang, X. Cu(II) propionyl-thiazole thiosemicarbazone complexes: Crystal structure, inhibition of human topoisomerase IIα, and activity against breast cancer Open J. Med. Chem. 2018, 8, 30–46.

- Morris, H.; Ngo, L.; Wilson, J.T.; Medawala, W.; Brown, A.R.; Conner, J.D.; Fabunmi, F.; Cashman, D.J.; Lisic, E.; Yu, T.; et al. Structural and metal ion effects on human topoisomerase IIα inhibition by α-(N)-heterocyclic thiosemicarbazones. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 90–99.

- Sandhaus, ; Taylor, R.; Edwards, T.; Huddleston, A.; Wooten, Y.; Venkatraman, R.; Weber, R.T.; González-Sarrías, A.; Martin, P.M.; Cagle, P.; et al. A novel copper(II) complex identified as a potent drug against colorectal and breast cancer cells and as a poison inhibitor for human topoisomerase IIα. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2016, 64, 45–49.

- Bacher, F.; Enyedy, É.; Nagy, N.V.; Rockenbauer, A.; Bognár, G.M.; Trondl, R.; Novak, M.S.; Klapproth, E.; Kiss, T.; Arion, V.B. Copper(II) complexes with highly water-soluble L- and D-proline-thiosemicarbazone conjugates as potential inhibitors of Topoisomerase IIα. Chem. 2013, 52, 8895–8908.

- Bisceglie, F.; Musiari, A.; Pinelli, S.; Alinovi ,, R.; Menozzi, I.; Polverini ,, E.; Tarasconi, P.; Tavone ,, M.; Pelosi, G. Quinoline-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones and their Cu(II) and Ni(II) complexes as topoisomerase IIa J. Inorg. Biochem. 2015, 152, 10–19.

- Chen, ; Huang, Y.W.; Liu, G.; Afrasiabi, Z.; Sinn, E.; Padhye, S.; Ma, Y. The cytotoxicity and mechanisms of 1,2-naphthoquinone thiosemicarbazone and its metal derivatives against MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. . 2004, 197, 40–48.

- Palanimuthu, ; Shinde, S.V.; Somasundaram, K.; Samuelson, A.G. In vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of copper bis(thiosemicarbazone) complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 722–734.

- Nair, R.S.; Potti, M.E.; Thankappan, R.; Chandrika, S.K.; Kurup, M.R.; Srinivas, P. Molecular trail for the anticancer behavior of a novel copper carbohydrazone complex in BRCA1 mutated breast Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 1501–1514.

- Arjmand, ; Jamsheera, A.; Afzal, M.; Tabassum, S. Enantiomeric specificity of biologically significant Cu(II) and Zn(II) chromone complexes towards DNA. Chirality 2012, 24, 977–986.

- Duff, ; Thangella, V.R.; Creaven, B.S.; Walsh, M.; Egan, D.A. Anti-cancer activity and mutagenic potential of novel copper(II) quinolinone Schiff base complexes in hepatocarcinoma cells. Eur. J. Pharm. 2012, 689, 45–55.

- Khan, R.A.; Usman, M.; Dhivya, R.; Balaji, P.; Alsalme, A.; AlLohedan, H.; Arjmand, F.; AlFarhan, K.; Akbarsha, M.A.; Marchetti, F.; et al. Heteroleptic copper(I) complexes of “scorpionate” bis-pyrazolyl carboxylate ligand with auxiliary phosphine as potential anticancer agents: An insight into cytotoxic mode. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45229–45246.