| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Raffaele Ornello | + 2012 word(s) | 2012 | 2021-06-01 09:51:26 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | + 278 word(s) | 2290 | 2021-08-23 04:42:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

Increased susceptibility to migraine during menstruation and in perimenopause is probably due to fluctuations in estrogen levels; rapid falls in estrogen levels are deemed responsible for an increased susceptibility to migraine. Menstrual migraine is characterized by long, severe, and poorly treatable headaches, for which the use of long-acting triptans and/or combined treatment with triptans and common analgesics is advisable. Short-term prophylaxis with triptans and/or estrogen treatment is another viable option in women with regular menstrual cycles or treated with combined hormonal contraceptives; conventional prevention may also be considered depending on the attack-related disability and the presence of attacks unrelated to menstruation. In women with perimenopausal migraine, hormonal treatments should aim at avoiding estrogen fluctuations.

1. Pathogenesis of hormone-related migraine

Migraine is a common headache disorder affecting 14% of people worldwide [1]. Migraine commonly affects young people and especially women; indeed, the prevalence of migraine is three to four times higher in women compared with men [1][2][3]. Different mechanisms might explain the female predominance of migraine, including the migraine-enhancing role of female sex hormones and a higher genetic heritability in women compared with men [4]. Of note, migraine prevalence is the same in women and in men during childhood, while a higher prevalence of migraine in women than in men is found only after puberty, when women start menstruating [5]. According to the so-called “estrogen withdrawal hypothesis”, the cycles of rise and fall in estrogen levels typical of the female fertile period are deemed responsible for an increased susceptibility to migraine in women [6]. Estrogen levels undergo a sudden fall during the days immediately preceding menstruation [7][8]. Hence, the highest susceptibility to migraine is in the perimenstrual period. The years immediately preceding and following the menopause also pose women at an increased risk of having severe migraine [9] due to the rapid fluctuations in estrogen levels that accompany this phase of the female reproductive cycle.

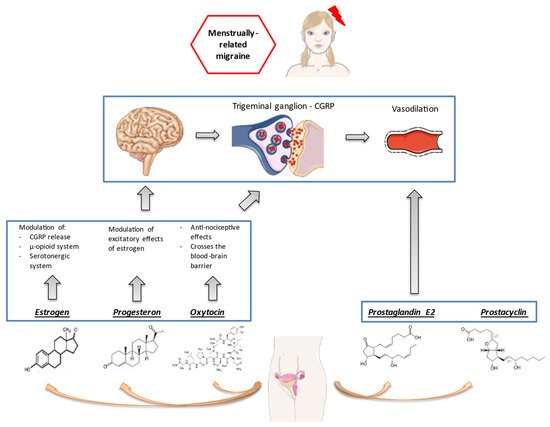

Sex hormones influence nociceptive processing, acting on both central and peripheral pathways [10]. Animal studies have found a broad localization of estrogen receptors in brain structures involved in migraine generation, including the trigeminal ganglion [11] and pain-processing structures within the brain [12]. At a central level, estrogens can activate the endogenous opioid system that controls pain sensations [13] and modulate the levels of oxytocin, a neurohormone released by the hypothalamus, which can exert an anti-migraine effect [14]. Notably, both estrogens [15] and oxytocin [16] might act on the trigeminal ganglion and modulate the release of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), which is implied in the generation of migraine pain. Progestins might also attenuate pain responses via conversion to the neurosteroid allopregnanolone, as suggested by animal evidence [17]. Taken all together, female sex hormones influence the susceptibility to migraine, acting through a complex interplay of central and peripheral pathways (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Female sex hormones and pathogenesis of menstrual migraine. From: J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2263.

2. Burden of Menstrual and Perimenopausal Migraine

The influence of female hormonal fluctuations on migraine is so remarkable that menstrual migraine (MM) is recognized by the current international classification as a distinct headache disorder [18]. In detail, pure menstrual migraine occurs exclusively on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles and at no other times of the cycle, while menstrual-related migraine occurs on day 1 ± 2 of menstruation in at least two out of three menstrual cycles, and additionally at other times of the cycle [18]. Differently from MM, perimenopausal migraine is not recognized as an independent clinical entity.

MM affects 3% of young women [19], with a peak of 22% in women aged 30–34 years [20]. According to several studies, migraine attacks occurring during the perimenstrual period are longer, more severe, have more associated symptoms, and are less responsive to acute medication compared with non-menstrual migraine attacks [21][22][23][24]. Menstruation is a poorly controllable hormonal trigger which exposes women to anticipatory anxiety of headaches, so-called “cephalalgiaphobia” [25]; this fear of headache could lead, in turn, to increased consumption of painkillers [26].

The reported prevalence of migraine during the menopause is 10–29% [9]. The years immediately preceding and following the menopause are characterized by an increased susceptibility to migraine [27][28] due to the frequent rise and fall of estrogen levels before reaching stable low levels years after the menopause [9]. After natural menopause, migraine usually improves [28][29], while women undergoing surgical menopause have a high risk of migraine worsening, possibly due to a sudden fall in estrogen levels [30][31]. The proportion of women reporting postmenopausal migraine worsening is particularly high in headache clinics, possibly due to selection bias [9][32].

3. Acute Treatment of Menstrual Migraine

3.1. Triptans

Randomized controlled trials and open-label studies have established the efficacy of sumatriptan [33][34][35], frovatriptan [36], naratriptan [37], zolmitriptan [38], and almotriptan [39] for the acute treatment of MM. All triptans were more effective than placebo in relieving pain during the first 2–4 h; however, most triptans were not superior over placebo in preventing migraine recurrence within 24 h from taking the drug [33][34]. Frovatriptan had better performances over the other triptans [40][41][42], possibly due to its longer half-life; hence, it could be advisable for use in MM, whose attacks are usually longer compared with those in the intermenstrual period [4].

3.2. Common Analgesics

The use of common analgesics in MM is justified by the increased release of prostaglandins during the perimenstrual period, which leads not only to perimenstrual pain, but also to an increased proneness to migraine [1][2][3]. Mefenamic acid, an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis, effectively treated MM in an early trial [43]. The commonly used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase enzymes [44] and can therefore be used in the acute treatment of MM, especially in women with dysmenorrhea.

3.3. General Considerations

It is important that drugs are taken soon after the beginning of pain, when it is still mild, to maximize their efficacy [35]. Not only the type of drugs, but also their mode of administration can influence their effectiveness in the acute management of MM; as MM is associated with an increased occurrence of gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, using non-oral formulations can contribute to increasing the effectiveness of acute treatments. Triptans and common analgesics act on different pathways; therefore, combining triptans with analgesics is an alternative approach to effectively treat MM. The available trials confirmed the efficacy of sumatriptan plus naproxen [45][46][47][48] and of frovatriptan plus dexketoprofen [49]. Common analgesics can also be used as a rescue treatment if triptans fail.

4. Prevention of Menstrual Migraine

The available migraine preventive agents are also effective on MM [4][50]. However, migraine tends to have a menstrual-related pattern even under effective prevention, with more frequent episodes in the perimenstrual than in the non-menstrual period [51][52]. This means that conventional preventatives cannot counterbalance the hormonal trigger. For this reason, specific hormonal strategies may be needed if a woman continues to consistently experience disabling menstrual attacks despite effective ongoing prevention for non-menstrual attacks.

Preventive treatment is started when migraine significantly interferes with the patient’s life [53]. In the case of MM, and mostly pure menstrual migraine, the impairment in quality of life can be severe, although only during a few days each month. Hence, common migraine preventatives, which are prescribed for daily use, might not have a net benefit. It is useful to plan MM-specific strategies for prevention, especially in women with pure MM. Such strategies include short-term prevention and hormonal manipulation.

4.1. Short-Term Prevention with Triptans or NSAIDs

Short-term prevention of MM is particularly useful in women taking oral contraceptives or with very regular menstrual cycles, in whom the period of maximum susceptibility to migraine is easily predictable. It can also be applied as an integration to standard prophylaxis in women with menstrual-related migraine not adequately controlled by standard prevention. This kind of treatment focuses on decreasing the burden of migraine during the days of highest susceptibility, while avoiding continuous prophylaxis and its potential adverse events. When considering a short-term prophylaxis, it should be kept in mind that natural menstrual cycles are subject to huge variations [54]. The available trials have assessed the efficacy of common analgesics, including naproxen [5] and nimesulide [6], and several triptans, including frovatriptan [7][8][9], naratriptan [10][11], and zolmitriptan [12] (Table 1); all those drugs were taken for 5 to 14 days around the start of menstruation. The trials’ results are largely positive, with the highest quality of evidence available for frovatriptan and naratriptan [13]. However, the daily use of triptans for the short-term prevention of MM has the drawback of possible ineffectiveness in women with irregular duration of menstrual cycles. Besides, the daily use of triptans can expose women to medication overuse [14]. It might be advisable to prescribe triptans as short-term prevention only to women with very regular menstrual cycles or under combined hormonal treatments and pure MM to maximize efficacy while minimizing the risk of medication overuse.

Table 1. Summary of drugs for the short-term prophylaxis of menstrual migraine. RCT indicates randomized controlled trial.

| Drug | Available Studies | Treatment Protocol | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSAIDs | |||

| Naproxen | 1 RCT [64] | 500 mg twice daily for 14 days for 3 cycles | Significant reduction in number, duration, and severity of attacks compared with placebo only during the 2nd and 3rd cycle |

| Nimesulide | 1 RCT [65] | 100 mg thrice daily for 10 days for 3 cycles | Significant reduction in pain intensity and duration compared with placebo during all the cycles |

| Triptans | |||

| Frovatriptan | 2 RCTs, 1 open-label extension [66,67,68] | 2.5 mg daily or twice daily for 6 days | Significant reduction in headache days, headache intensity, headache duration, and use of rescue medication; twice daily formulation better than daily formulation |

| Naratriptan | 1 RCT [70] | 1 mg or 2.5 mg twice daily for 5 days for 3 cycles | Significant reduction in headache days, headache intensity, headache duration, and use of rescue medication; significant improvement in quality of life; 2.5 mg dose better than 1 mg dose |

| Zolmitriptan | 1 RCT [71] | 2.5 mg twice or thrice daily for 7 days for 3 cycles | Significant reduction in headache days, pain recurrence, and rescue medication with both doses |

| Hormone supplementation | |||

| Percutaneous estradiol | 3 RCTs [75,76,77] | 7–10 days for 2–3 cycles | Significant reduction in headache days and acute medication use, only during the treatment, with subsequent rebound headache; good tolerability profile |

| Transdermal 17 β-estradiol | 1 RCTs [78] | 6 days for 3 cycles | Estradiol effective only if synchronized with menstruation |

| Conjugated equine estrogens | 1 Open-label [74] | 7 days (hormone-free interval of a combined contraceptive) for 2 cycles | At least 50% reduction in monthly headache days in all treated women; improvement in menstrual symptoms |

4.2. Hormonal Prevention

Hormonal manipulation strategies are an alternative option for the management of MM based on the estrogen withdrawal hypothesis. These strategies aim at preventing MM by reducing or suppressing the fall in estrogen levels that precedes menstruation. This goal can be achieved by short-term hormonal supplementation or by the continuous use of exogenous hormones in fixed doses, without hormone-free intervals. It should be kept in mind that the intermittent formulations of oral combined hormonal contraceptives usually exacerbate migraine as they lead to higher fluctuations in estrogen levels compared with natural menstrual cycles [55][56].

Short-term estrogen supplementation can be done with estrogen gel [57][58][59] or patches [60][61]. An open-label study suggested the efficacy of an oral contraceptive containing 20 μg ethinyl estradiol on days 1 to 21, supplemented with 0.9 mg conjugated equine estrogens on days 22 to 28, for the prevention of MM [56]. An alternative strategy to prevent MM in women seeking contraception is to use specific formulations of low-dose estrogens and/or progestins, such as estradiol valerate plus dienogest [62]. Continuous administration of estrogen, without [63] or with a reduced time hormone-free interval [64], or the use of non-oral formulations, such as the vaginal ring [65], also showed efficacy in decreasing the burden of MM.

An alternative modality of hormonal treatment for MM is the use of phytoestrogen [66][67]. Using phytoestrogens instead of the usual estrogen formulations could also mitigate the vascular risk associated with combined hormonal contraception [68], which is an important concern in women with migraine [69].

Hormonal treatments differentially affect migraine with and without aura, as migraine without aura tends to follow a menstrual-related pattern more frequently than migraine with aura [70][71]. It is likely that women with migraine with aura undergo migraine exacerbations if exposed to combined hormonal contraceptives and mostly those with high estrogen doses. Besides, women with migraine with aura have a highly increased vascular risk, which could be further increased by using combined hormonal contraceptives [72]. Therefore, the use of exogenous estrogens should be best avoided in women reporting auras.

4.3. Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Non-pharmacological treatments can be useful in women with MM who refuse or have contraindications to hormonal or other pharmacological treatments; in addition, they can be used as adjunctive short-term treatments. There is evidence of efficacy for magnesium [73], vitamin E [74], and vitex agnus-castus [15]. Notably, magnesium is also useful for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome [16]. Transcranial direct current stimulation also showed effectiveness in MM [17]; however, this technique is of limited availability.

5. Treatment of Perimenopausal Migraine

5.1 Hormonal Treatments

Hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) is usually prescribed to reduce the vasomotor symptoms associated with the menopausal transition [75][76]. However, HRT can worsen migraine [32][77][78]. To limit migraine worsening after the menopause, different strategies are viable based on the estrogen withdrawal hypothesis, including the continuous rather than intermittent administration of combined hormonal treatments [79], the intrauterine or transdermal rather than oral administration of estrogen [80], and the administration of non-estrogen compounds such as tibolone [81]. An alternative strategy could be the use of phytoestrogens such as soy isoflavones, which can control menopausal symptoms [82] together with hormone-related migraine. The types and doses of estrogens and progestins in HRT can also have a different impact on migraine. As high-estrogen states can increase the susceptibility to migraine with aura [71], the use of the lowest possible doses of estrogens can contribute to avoiding the exacerbation of migraine during the menopausal transition [83]. Referring to progestins, the use of products without androgenic properties or natural progesterone [84] or non-oral routes of administration [85] might be beneficial to migraine [86].

5.2 Non-hormonal Treatments

When considering hormonal treatments for postmenopausal women, the possible benefits should be compared with the risk of cerebrovascular events, which is increased both by migraine itself and by estrogens [72][87][88], even at the lowest doses [69]. Antidepressants such as escitalopram or venlafaxine can be used to control both vasomotor symptoms and migraine in postmenopausal women in whom HRT is contraindicated [89][90]. Among non-pharmacologic treatments, vitamin E, acupuncture, and physical exercise have modest evidence of effect on both vasomotor symptoms and migraine [91].

References

- Durham, P.L.; Vause, C.V.; Derosier, F.; McDonald, S.; Cady, R.; Martin, V. Changes in salivary prostaglandin levels during menstrual migraine with associated dysmenorrhea. Headache 2010, 50, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannix, L.K. Menstrual-Related Pain Conditions: Dysmenorrhea and Migraine. J. Women’s Health 2008, 17, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, M.; Wienecke, T.; Olesen, J.; Ashina, M. Prostaglandin E(2) induces immediate migraine-like attack in migraine patients without aura. Cephalalgia 2012, 32, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allais, G.; Del Rio, M.S.; Diener, H.-C.; Benedetto, C.; Pfeil, J.; Schäuble, B.; von Oene, J. Perimenstrual migraines and their response to preventive therapy with topiramate. Cephalalgia 2010, 31, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sances, G.; Martignoni, E.; Fioroni, L.; Blandini, F.; Facchinetti, F.; Nappi, G. Naproxen sodium in menstrual migraine prophylaxis: A double-blind placebo controlled study. Headache 1990, 30, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacovazzo, M.; Gallo, M.F.; Guidi, V.; Rico, R.; Scaricabarozzi, I. Nimesulide in the Treatment of Menstrual Migraine. Drugs 1993, 46 (Suppl. 1), 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandes, J.L.; Poole, A.; Kallela, M.; Schreiber, C.P.; MacGregor, E.A.; Silberstein, S.D.; Tobin, J.; Shaw, R. Short-term frovatriptan for the prevention of difficult-to-treat menstrual migraine attacks. Cephalalgia 2009, 29, 1133–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, E.A.; Brandes, J.L.; Silberstein, S.; Jeka, S.; Czapinski, P.; Shaw, B.; Pawsey, S. Safety and Tolerability of Short-Term Preventive Frovatriptan: A Combined Analysis. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2009, 49, 1298–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silberstein, S.D.; Elkind, A.H.; Schreiber, C.; Keywood, C. A randomized trial of frovatriptan for the intermittent prevention of menstrual migraine. Neurology 2004, 63, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, L.K.; Savani, N.; Landy, S.; Valade, M.; Shackelford, S.; Ames, M.H.; Jones, M.W. Efficacy and Tolerability of Naratriptan for Short-Term Prevention of Menstrually Related Migraine: Data from Two Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Studies. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2007, 47, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, L.; Mannix, L.K.; Landy, S.; Silberstein, S.; Lipton, R.B.; Putnam, D.G.; Watson, C.; Jöbsis, M.; Batenhorst, A.; O’Quinn, S. Naratriptan as short-term prophylaxis of menstrually associated migraine: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2001, 41, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, M.M.; Hee, A.; Emeribe, U.; Silberstein, S. Oral zolmitriptan in the short-term prevention of menstrual migraine: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. CNS Drugs 2008, 22, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetvik, K.G.; MacGregor, E.A. Menstrual migraine: A distinct disorder needing greater recognition. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberstein, S.; Patel, S. Menstrual migraine: An updated review on hormonal causes, prophylaxis and treatment. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014, 15, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosini, A.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Coppola, G.; Pierelli, F. Use of Vitex agnus-castus in migrainous women with premenstrual syndrome: An open-label clinical observation. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2012, 113, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allais, G.; Gabellari, I.C.; Burzio, C.; Rolando, S.; De Lorenzo, C.; Mana, O.; Benedetto, C. Premenstrual syndrome and migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 33 (Suppl. 1), 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickmann, F.; Stephani, C.; Czesnik, D.; Klinker, F.; Timäus, C.; Chaieb, L.; Paulus, W.; Antal, A. Prophylactic treatment in menstrual migraine: A proof-of-concept study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 354, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]