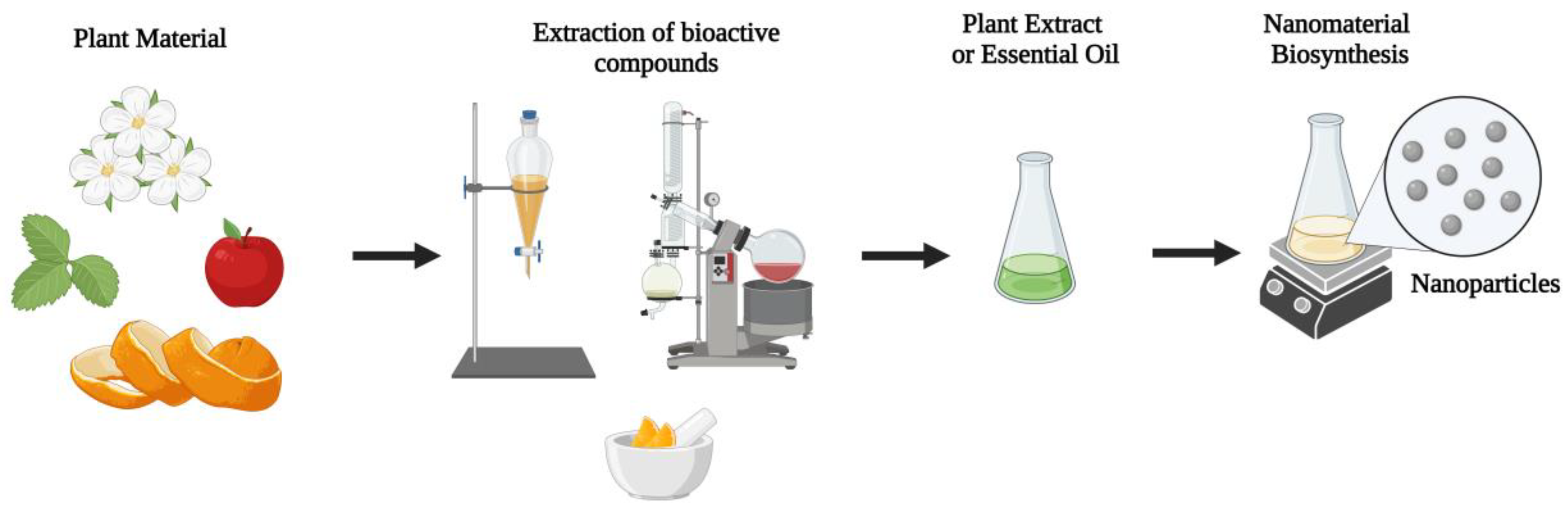

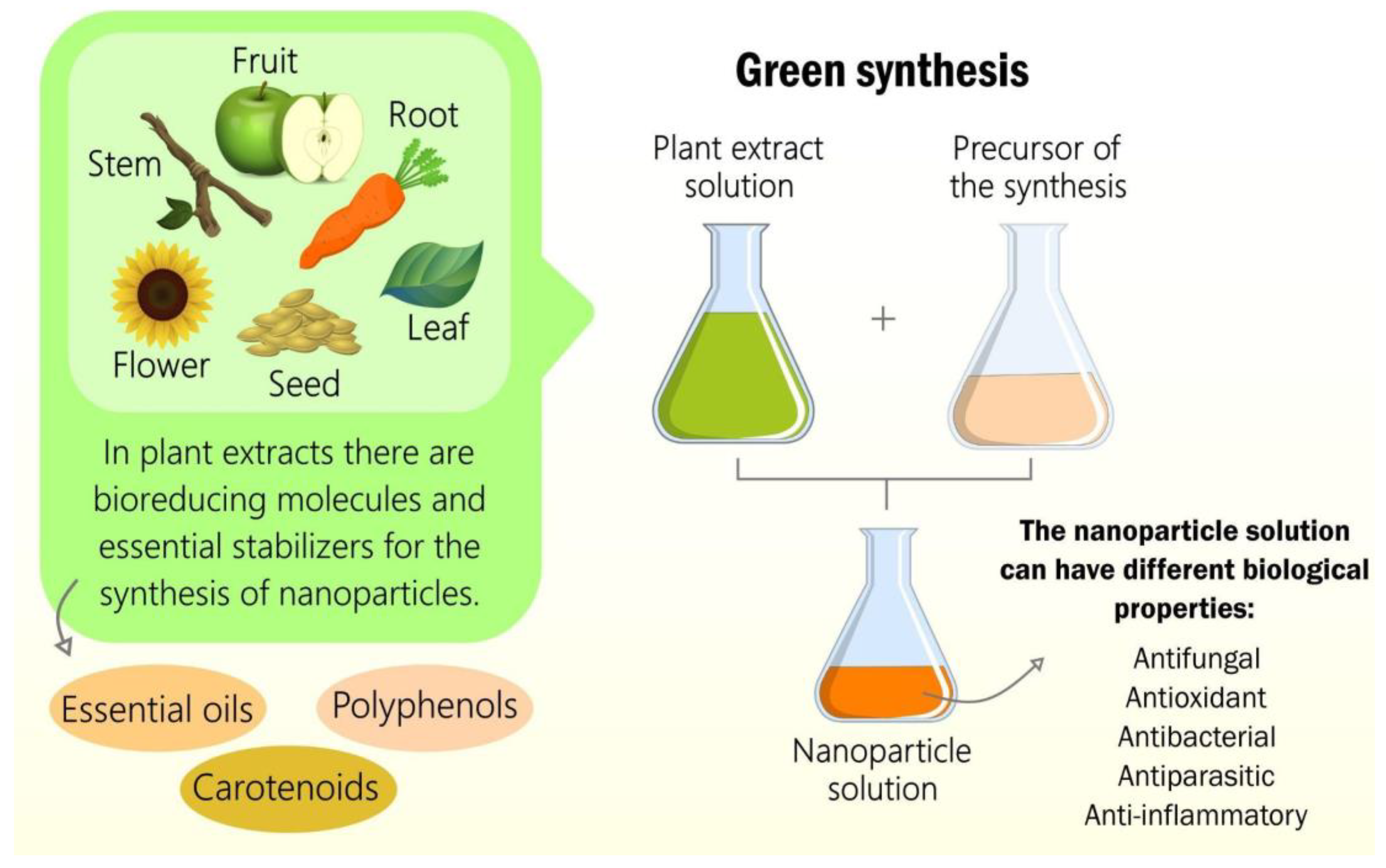

Plant extracts and essential oils have a wide variety of molecules with potential application in different fields such as medicine, the food industry, and cosmetics. Furthermore, these plant derivatives are widely interested in human and animal health, including potent antitumor, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and bactericidal activity. Given this diversity, different methodologies were needed to optimize the extraction, purification, and characterization of each class of biomolecules. In addition, these plant products can still be used in the synthesis of nanomaterials to reduce the undesirable effects of conventional synthesis routes based on hazardous/toxic chemical reagents and associate the properties of nanomaterials with those present in extracts and essential oils.

- plant extracts

- essential oils

- green synthesis

1. Introduction

2. Plant-Based Antibacterial Green Nanomaterials

| Nanomaterials | Plant-Based Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles | Antibacterial Properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs | Acacia lignin | Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus circulam, and Ralstonia eutropha. | [56] |

| AgNPs | Dodonaea viscosa | Antibacterial activity against Streptococcus pyogene. | [57] |

| AgNPs | Euterpe oleracea | Antibacterial dressings against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. | [58] |

| AgNPs | Pedalium murex | Antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Micrococcus flavus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pheumoniae, and Bacillus pumilus. | [59] |

| AgNPs | Beta vulgaris | Antibacterial textiles against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Escherichia coli. | [60] |

| AuNPs | Pistacia atlantica | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [52] |

| AuNPs | Amorphophallus paeoniifolius | Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii, Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, and Staphylococcus aureus. | [61] |

| AuNPs | Jatropha integerrima Jacq. | Antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and klebsiella pneumoniae. | [62] |

| AuNPs | Citrus maxima | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli. | [63] |

| Al2O3NPs | Prunus xyedonesis | Antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [64] |

| Al2O3NPs | Cymbopogan citratus | Antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [65] |

| MgONPs | Sargassum wightii | Antibacterial activity against Streptococcus pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Aeromonas baumannii. | [66] |

| MgONPs | Annona squamosa | Antibacterial activity against Pactobacterium carotovorume. | [67] |

| MgONPs | Rhododendron arboreum | Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Spectrococous mutans, and Proteus vulgaris. | [68] |

| MgONPs | Saussurea costus | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [53] |

| ZnONPs | Pongamia pinnata | Antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [69] |

| ZnONPs | Ailanthus altissima | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. | [70] |

| ZnONPs | Medicago sativa L. | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus epidermidis, Lactococcus lactis, and Lactobacillus casei. | [55] |

| TiO2NPs | Psidium guajava | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. | [71] |

| TiO2NPs | Mentha arvensis | Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, and Staphylococcus aureus. | [72] |

| TiO2NPs | Trigonella foenum-graecum | Antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Bacillus subtilis, and Yersinia enterocolitica. | [73] |

| TiO2NPs | Azadirachta indica | Antibacterial activity against Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli. | [74] |

| TiO2NPs | Hypsizygus ulmarius | Antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacillus cereus. | [75] |

| TiO2NPs | Pristine pomegranate peel extract | Bacterial disinfection against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [76] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules28073060

References

- Süntar, I. Importance of ethnopharmacological studies in drug discovery: Role of medicinal plants. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1199–1209.

- Alasmari, A. Phytomedicinal Potential Characterization of Medical Plants (Rumex nervosus and Dodonaea viscose). J. Biochem. Technol. 2020, 11, 113–121.

- Horstmanshoff, M. Ancient medicine between hope and fear: Medicament, magic and poison in the Roman Empire. Eur. Rev. 1999, 7, 37–51.

- Sargin, S.A. Potential anti-influenza effective plants used in Turkish folk medicine: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113319.

- Mahady, G.B. Medicinal Plants for the Prevention and Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2005, 11, 2405–2427.

- Stéphane, F.F.Y.; Jules, B.K.J.; Batiha, G.E.-S.; Ali, I.; Bruno, L.N. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Medicinal Plants and Herbs. Nat. Med. Plants 2022.

- Hao, D.C.; Gu, X.J.; Xiao, P.G. Medicinal Plants: Chemistry, Biology and Omics; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015.

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of Terpenes and Recent Advances in Plant Protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5710.

- Naboulsi, I.; Aboulmouhajir, A.; Kouisni, L.; Bekkaoui, F.; Yasri, A. Plants extracts and secondary metabolites, their extraction methods and use in agriculture for controlling crop stresses and improving productivity: A review. Acad. J. Med. Plants 2018, 6, 223–240.

- Eddin, L.; Jha, N.; Meeran, M.; Kesari, K.; Beiram, R.; Ojha, S. Neuroprotective Potential of Limonene and Limonene Containing Natural Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4535.

- Vieira, A.; Beserra, F.; Souza, M.; Totti, B.; Rozza, A. Limonene: Aroma of innovation in health and disease. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 283, 97–106.

- Exposito, O.; Bonfill, M.; Moyano, E.; Onrubia, M.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J. Biotechnological Production of Taxol and Related Taxoids: Current State and Prospects. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 9, 109–121.

- Kamatou, G.P.; Vermaak, I.; Viljoen, A.M.; Lawrence, B.M. Menthol: A simple monoterpene with remarkable biological properties. Phytochemistry 2013, 96, 15–25.

- Kurek, J. Alkaloids—Their Importance in Nature and Human Life; Intechopen: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/66742 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Bhambhani, S.; Kondhare, K.; Giri, A. Diversity in Chemical Structures and Biological Properties of Plant Alkaloids. Molecules 2021, 26, 3374.

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant Flavonoids: Chemical Characteristics and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377.

- Brodowska, K.; Brodowska, K.M. Natural Flavonoids: Classification, Potential Role, and Application of Flavonoid Analogues. Eur. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 7, 108–123.

- Afify, A.E.-M.M.R.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; El-Salam, S.M.A.; Omran, A.A. Biochemical changes in phenols, flavonoids, tannins, vitamin E, β–carotene and antioxidant activity during soaking of three white sorghum varieties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 203–209.

- Serrano, J.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Dauer, A.; Aura, A.-M.; Saura-Calixto, F. Tannins: Current knowledge of food sources, intake, bioavailability and biological effects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, S310–S329.

- Alcantara, R.G.L.; Joaquim, R.H.V.T.; Sampaio, S.F. Plantas Medicinais: O Conhecimento e Uso Popular. Rev. APS—Atenção Primária Saúde 2015, 18, 1–13.

- Fitzgerald, M.; Heinrich, M.; Booker, A. Medicinal Plant Analysis: A Historical and Regional Discussion of Emergent Complex Techniques. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1480.

- Barbosa, F.E.S.; Guimarães, M.B.L.; Dos Santos, C.R.; Bezerra, A.F.B.; Tesser, C.D.; De Sousa, I.M.C. Oferta de Práticas Integrativas e Complementares em Saúde na Estratégia Saúde da Família no Brasil. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36, e00208818.

- Filho, S.A.; Backx, B.P. Nanotecnologia e seus impactos na sociedade. Rev. Tecnol. Soc. 2020, 16, 1–15.

- Backx, B.P. Green Nanotechnology: Only the Final Product That Matters? Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 36, 3507–3509.

- Raja, R.K.; Hazir, S.; Balasubramani, G.; Sivaprakash, G.; Obeth, E.S.J.; Boobalan, T.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Raj, R.H.K.; Arun, A. Green Nanotechnology for the Environment. In Handbook of Microbial Nanotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022.

- Srivastava, S.; Bhargava, A. Tools and Techniques Used in Nanobiotechnology. In Green Nanoparticles: The Future of Nanobiotechnology; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 29–55.

- Backx, B.P.; dos Santos, M.S.; dos Santos, O.A.; Filho, S.A. The Role of Biosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles in Antimicrobial Mechanisms. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 762–772.

- Ocsoy, I.; Tasdemir, D.; Mazicioglu, S.; Tan, W. Nanotechnology in Plants. In Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer International Publishing AG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 164.

- Nasrollahzadeh, M.; Sajadi, S.M.; Sajjadi, M.; Issaabadi, Z. Chapter 1: An Introduction to Nanotechnology. In An Introduction to Green Nanotechnology; Interface Science and Technology; Nasrollahzadeh, M., Sajadi, S.M., Sajjadi, M., Issaabadi, Z., Atarod, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 28, pp. 113–143. ISBN 978-0-12-813586-0.

- Ali, S.; Shafique, O.; Mahmood, T.; Hanif, M.A.; Ahmed, I.; Khan, B.A. A Review about Perspectives of Nanotechnology in Agriculture. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 31, 116–121.

- Hischier, R.; Walser, T. Life cycle assessment of engineered nanomaterials: State of the art and strategies to overcome existing gaps. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 425, 271–282.

- Salieri, B.; Turner, D.A.; Nowack, B.; Hischier, R. Life Cycle Assessment of Manufactured Nanomaterials: Where Are We? NanoImpact 2018, 10, 108–120.

- Dos Santos, M.S.; Backx, B.P. Fatores que influenciam a estabilidade das nanopartículas de prata dispersas em própolis. Acta Apic. Bras. 2020, 8, e7805.

- Behzad, F.; Naghib, S.M.; Kouhbanani, M.A.J.; Tabatabaei, S.N.; Zare, Y.; Rhee, K.Y. An overview of the plant-mediated green synthesis of noble metal nanoparticles for antibacterial applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 94, 92–104.

- Parveen, K.; Banse, V.; Ledwani, L. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Their advantages and disadvantages. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing LLC: Melville, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 1724, p. 020048.

- Jadoun, S.; Arif, R.; Jangid, N.K.; Meena, R.K. Green synthesis of nanoparticles using plant extracts: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 355–374.

- Mubayi, A.; Chatterji, S.; Rai, P.K.; Watal, G. Evidence Based Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2012, 3, 519–525.

- Dos Santos, M.S.; Filho, S.A.; Backx, B.P. Bionanotechnology in Agriculture: A One Health Approach. Life 2023, 13, 509.

- Dos Santos, M.S.; Dos Santos, O.A.L.; Filho, S.A.; Santana, J.C.D.S.; De Souza, F.M.; Backx, B.P. Can Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles be Efficient all Year Long? Nanomater. Chem. Technol. 2019, 1, 32–36.

- Gour, A.; Jain, N.K. Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 844–851.

- Sant’Anna-Santos, B.; Da Silva, L.C.; Azevedo, A.A.; Aguiar, R. Effects of simulated acid rain on leaf anatomy and micromorphology of Genipa americana L. (Rubiaceae). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2006, 49, 313–321.

- Piccolella, S.; Crescente, G.; Pacifico, F.; Pacifico, S. Wild Aromatic Plants Bioactivity: A Function of Their (Poly)Phenol Sea-sonality? A Case Study from Mediterranean Area. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 785–799.

- Almeida, C.D.L.; Xavier, R.M.; Borghi, A.A.; dos Santos, V.F.; Sawaya, A.C.H.F. Effect of seasonality and growth conditions on the content of coumarin, chlorogenic acid and dicaffeoylquinic acids in Mikania laevigata Schultz and Mikania glomerata Sprengel (Asteraceae) by UHPLC–MS/MS. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2017, 418, 162–172.

- Heffernan, N.; Smyth, T.; FitzGerald, R.J.; Vila-Soler, A.; Mendiola, J.A.; Ibáñez, E.; Brunton, N. Comparison of extraction methods for selected carotenoids from macroalgae and the assessment of their seasonal/spatial variation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 221–228.

- Choi, S.; Johnston, M.; Wang, G.-S.; Huang, C. A seasonal observation on the distribution of engineered nanoparticles in municipal wastewater treatment systems exemplified by TiO2 and ZnO. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 1321–1329.

- Bouarab-Chibane, L.; Forquet, V.; Lantéri, P.; Clément, Y.; Léonard-Akkari, L.; Oulahal, N.; Degraeve, P.; Bordes, C. Antibacterial Properties of Polyphenols: Characterization and QSAR (Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship) Models. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 829.

- Nascimento, G.G.F.; Locatelli, J.; Freitas, P.C.; Silva, G.L. Antibacterial activity of plant extracts and phytochemicals on antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2000, 31, 247–256.

- Al-Rifai, A.; Aqel, A.; Al-Warhi, T.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Al-Othman, Z.A.; Badjah-Hadj-Ahmed, A.Y. Antibacterial, Antioxidant Activity of Ethanolic Plant Extracts of Some Convolvulus Species and Their DART-ToF-MS Profiling. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–9.

- Chingwaru, C.; Bagar, T.; Chingwaru, W. Aqueous extracts of Flacourtia indica, Swartzia madagascariensis and Ximenia caffra are strong antibacterial agents against Shigella spp., Salmonella typhi and Escherichia coli O157. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 128, 119–127.

- Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M.; Nowak, A.; Czyzowska, A. Plant extracts rich in polyphenols: Antibacterial agents and natural preservatives for meat and meat products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 149–178.

- de Carvalho, J.J.V.; Boaventura, F.G.; Silva, A.D.C.R.D.; Ximenes, R.L.; Rodrigues, L.K.C.; Nunes, D.A.D.A.; de Souza, V.K.G. Bactérias multirresistentes e seus impactos na saúde pública: Uma responsabilidade social. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e58810616303.

- Hamelian, M.; Hemmati, S.; Varmira, K.; Veisi, H. Green synthesis, antibacterial, antioxidant and cytotoxic effect of gold nanoparticles using Pistacia Atlantica extract. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 93, 21–30.

- Amina, M.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Alarfaj, N.A.; El-Tohamy, M.F.; Oraby, H.F.; Al Hamoud, G.A.; Bukhari, S.I.; Moubayed, N.M.S. Biogenic green synthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Saussurea costus biomasses for a comprehensive detection of their antimicrobial, cytotoxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells and photocatalysis potentials. PloS ONE 2020, 15, e0237567.

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Huang, D.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.; Sun, D.; Huang, J.; Li, Q. Plant-mediated synthesis of size-controllable Ni nanoparticles with alfalfa extract. Mater. Lett. 2014, 122, 166–169.

- Król, A.; Railean-Plugaru, V.; Pomastowski, P.; Buszewski, B. Phytochemical investigation of Medicago sativa L. extract and its potential as a safe source for the synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles: The proposed mechanism of formation and antimicrobial activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 31, 170–180.

- Aadil, K.R.; Pandey, N.; Mussatto, S.I.; Jha, H. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using acacia lignin, their cytotoxicity, catalytic, metal ion sensing capability and antibacterial activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103296.

- Anandan, M.; Poorani, G.; Boomi, P.; Varunkumar, K.; Anand, K.; Chuturgoon, A.A.; Saravanan, M.; Prabu, H.G. Green synthesis of anisotropic silver nanoparticles from the aqueous leaf extract of Dodonaea viscosa with their antibacterial and anticancer activities. Process. Biochem. 2019, 80, 80–88.

- Santana, J.; Antunes, S.; Bonelli, R.; Backx, B. Development of Antimicrobial Dressings by the Action of Silver Nanoparticles Based on Green Nanotechnology. Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 2023, 12, 35.

- Anandalakshmi, K.; Venugobal, J.; Ramasamy, V. Characterization of silver nanoparticles by green synthesis method using Pedalium murex leaf extract and their antibacterial activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2016, 6, 399–408.

- dos Santos, O.A.L.; de Araujo, I.; da Silva, F.D.; Sales, M.N.; Christoffolete, M.A.; Backx, B.P. Surface modification of textiles by green nanotechnology against pathogenic microorganisms. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100206.

- Nayem, S.M.A.; Sultana, N.; Haque, M.; Miah, B.; Hasan, M.; Islam, T.; Awal, A.; Uddin, J.; Aziz, M.; Ahammad, A. Green synthesis of gold and silver nanoparticles by using Amorphophallus paeoniifolius tuber extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 4773.

- Suriyakala, G.; Sathiyaraj, S.; Babujanarthanam, R.; Alarjani, K.M.; Hussein, D.S.; Rasheed, R.A.; Kanimozhi, K. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Jatropha integerrima Jacq. Flower extract and their antibacterial activity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101830.

- Yuan, C.; Huo, C.; Gui, B.; Cao, W. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Citrus maxima peel extract and their catalytic/antibacterial activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 523–530.

- Ghotekar, S. Plant extract mediated biosynthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles- a review on plant parts involved, characterization and applications. Nanochem. Res. 2019, 4, 163–169.

- Ansari, M.A.; Khan, H.M.; Alzohairy, M.A.; Jalal, M.; Ali, S.G.; Pal, R.; Musarrat, J. Green synthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles and their bactericidal potential against clinical isolates of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 153–164.

- Pugazhendhi, A.; Prabhu, R.; Muruganantham, K.; Shanmuganathan, R.; Natarajan, S. Anticancer, antimicrobial and photocatalytic activities of green synthesized magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgONPs) using aqueous extract of Sargassum wightii. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2018, 190, 86–97.

- Sharma, S.K.; Khan, A.U.; Khan, M.; Gupta, M.; Gehlot, A.; Park, S.; Alam, M. Biosynthesis of MgO nanoparticles using Annona squamosa seeds and its catalytic activity and antibacterial screening. Micro Nano Lett. 2020, 15, 30–34.

- Singh, A.; Joshi, N.C.; Ramola, M. Magnesium oxide Nanoparticles (MgONPs): Green Synthesis, Characterizations and Antimicrobial activity. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2019, 12, 4644.

- Ghosh, M.; Nallal, V.U.; Prabha, K.; Muthupandi, S.; Razia, M. Synergistic antibacterial potential of plant-based Zinc oxide Nanoparticles in combination with antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 49, 2632–2635.

- Awwad, A.M.A. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) Using Ailanthus Altissima Fruit Extracts and Antibacterial Activity. Chem. Int. 2020, 6, 151–159.

- Santhoshkumar, T.; Rahuman, A.A.; Jayaseelan, C.; Rajakumar, G.; Marimuthu, S.; Kirthi, A.V.; Velayutham, K.; Thomas, J.; Venkatesan, J.; Kim, S.-K. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Psidium guajava extract and its antibacterial and antioxidant properties. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2014, 7, 968–976.

- Ahmad, W.; Jaiswal, K.K.; Soni, S. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by using Mentha arvensis leaves extract and its antimicrobial properties. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 2020, 50, 1032–1038.

- Subhapriya, S.; Gomathipriya, P. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles by Trigonella foenum-graecum extract and its antimicrobial properties. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 116, 215–220.

- Thakur, B.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, D. Green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and evaluation of their antibacterial activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 124, 223–227.

- Manimaran, K.; Loganathan, S.; Prakash, D.G.; Natarajan, D. Antibacterial and anticancer potential of mycosynthesized titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles using Hypsizygus ulmarius. Biomass-Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 1–9.

- AbuDalo, M.; Jaradat, A.; Albiss, B.; Al-Rawashdeh, N.A. Green synthesis of TiO2 NPs/pristine pomegranate peel extract nanocomposite and its antimicrobial activity for water disinfection. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103370.

- Shaikh, S.; Nazam, N.; Rizvi, S.M.D.; Ahmad, K.; Baig, M.H.; Lee, E.J.; Choi, I. Mechanistic Insights into the Antimicrobial Actions of Metallic Nanoparticles and Their Implications for Multidrug Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2468.

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Bharath, L.V.; Geetha, R. Broad Spectrum Antibacterial Silver Nanoparticle Green Synthesis: Characteriza-tion, and Mechanism of Action. In Green Synthesis, Characterization and Applications of Nanoparticles; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018.

- Moghadam, N.C.Z.; Jasim, S.A.; Ameen, F.; Alotaibi, D.H.; Nobre, M.A.L.; Sellami, H.; Khatami, M. Nickel oxide nanoparticles synthesis using plant extract and evaluation of their antibacterial effects on Streptococcus mutans. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1201–1210.

- Ahmad, A.; Wei, Y.; Syed, F.; Tahir, K.; Rehman, A.U.; Khan, A.; Ullah, S.; Yuan, Q. The effects of bacteria-nanoparticles interface on the antibacterial activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 102, 133–142.

- Das, B.; Dash, S.K.; Mandal, D.; Ghosh, T.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Tripathy, S.; Das, S.; Dey, S.K.; Das, D.; Roy, S. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles destroy multidrug resistant bacteria via reactive oxygen species mediated membrane damage. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 862–876.

- Akintelu, S.A.; Folorunso, A.S.; Folorunso, F.A.; Oyebamiji, A.K. Green synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles for biomedical application and environmental remediation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04508.

- Álvarez-Chimal, R.; García-Pérez, V.I.; Álvarez-Pérez, M.A.; Arenas-Alatorre, J. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using a Dysphania ambrosioides extract. Structural characterization and antibacterial properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111540.

- Ahmad, B.; Chang, L.; Satti, U.Q.; Rehman, S.U.; Arshad, H.; Mustafa, G.; Shaukat, U.; Wang, F.; Tong, C. Phyto-Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Using Various Plant Extracts. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 779.

- Gupta, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Li, C.-H.; Hussain, I.; Rotello, V.M. Combatting antibiotic-resistant bacteria using nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 415–427.