You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

|

Health Care Sciences & Services

Pertussis is a highly contagious respiratory infection caused by Bordetella pertussis bacterium. The mainstay of treatment is macrolide antibiotics that reduce transmissibility, shorten the duration of symptoms and decrease mortality in infants.

- Bordetella pertussis

- pertussis

- whooping cough

- macrolides

- macrolide resistance

1. Introduction

Pertussis, or whooping cough, is a highly contagious respiratory infection caused by Bordetella pertussis, a small Gram-negative rod bacterium. Despite extensive vaccinations, whooping cough is resurging in many countries including USA, UK and China [1]. The disease can manifest as a severe life-threatening illness, especially in unvaccinated young infants. A cornerstone of the clinical management of infants with recent onset of pertussis infection is, in addition to supportive care, antibiotic management by macrolide antibiotics. Macrolide treatment might ameliorate the disease when started early after infection onset, before the appearance of paroxysmal cough [2].

Macrolides (erythromycin (ERY), clarithromycin (CHL) and azithromycin (AZT)] are the first line antimicrobials used to treat pertussis patients. Several studies have shown their efficacy in vitro, and in clinical settings for clearance of B. pertussis [3,4,5,6].

The first B. pertussis strain with decreased sensitivity to macrolide antibiotics was detected in Arizona, USA in 1994 [7]. Since then, macrolide resistant B. pertussis has been detected in several countries, although it is rare. However, macrolide resistant B. pertussis has been increasingly reported in China during past decade, raising the concern of its potential transmission to other regions and countries.

2. Pertussis Diagnostics

Pertussis diagnostics can be divided into three main approaches: (1) culture, (2) nucleic acid detection (PCR) and (3) serology. Patient age, vaccination history and onset of the symptoms should be considered when choosing the correct diagnostic method [8]. Culture can be performed up to 2 weeks after the symptoms have appeared, before the bacteria is cleared by the immune defence. Specimen from freshly obtained nasopharyngeal (NP) samples should be cultured on Regan-Lowe (RL, charcoal) or Bordet-Gengou (BG, blood) agar containing cephalexin. Suspected B. pertussis specific colonies are further cultured on RL/BG agar (without cephalexin), and identified with e.g., slide agglutination test with specific anti-B. pertussis and anti-B. parapertussis sera or MALDI-TOF [8,9,10]. Specific nucleic acid identification (targeting IS481/ptxp) with PCR requires only a small amount of DNA for detection and identification of the bacterium and is therefore far more sensitive than culture. Furthermore, it can be used even three to four weeks after the onset of symptoms. Therefore, PCR-based approaches are more widely used than culture, especially with infants and small children. For school children and adults, serology is commonly used as there is less interference in antibodies induced from previous vaccinations and the only symptom may have been a prolonged cough (>3–4 weeks, culture nor PCR can be used). Serological diagnosis should be made based on the measurement of serum IgG antibodies against pertussis toxin [11]. Furthermore, laboratory confirmation of B. pertussis from clinical samples is needed before antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) is performed.

3. Epidemiology

The first macrolide resistant B. pertussis strain was identified in a 2-month-old infant from Yuma, Arizona, US in 1994 [7]. The isolate was highly resistant to erythromycin with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) > 64 µg/mL. However, the origin of this isolate was not known. Breakpoints to detect antimicrobial resistance of clinical B. pertussis isolates were not standardized but the reported resistant strains had MICs of >256 µg/mL with erythromycin (ERY) and clarithromycin (CHL) by Etest method suggesting macrolide resistance. Concurrently, seven additional B. pertussis isolates from the same area were tested, but macrolide resistance was not detected in these cases. In a review of 47 B. pertussis isolates from children in Utah, US, in 1985–1997, one isolate from January 1997 was resistant against erythromycin [12].

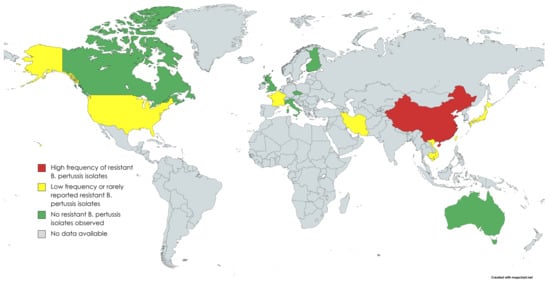

Since the first appearance of macrolide-resistant B. pertussis, macrolide susceptibility has been tested in thousands of cultured isolates all over the world (Table 1, Figure 1). In a study of 1030 isolates collected from various parts of the the US, five (0.5%) isolates were erythromycin resistant. Four out of five isolates were from Arizona (1994–1995) and one from Georgia (1995). All isolates initially showed the growth inhibition of B. pertussis by disc diffusion method, but after 5–7 days of incubation, novel bacterial colonies appeared on the plate inside the growth inhibition area, demonstrating heterogeneous phenotype [13]. In a review of 38 B. pertussis isolates from France in 2003, none of them were resistant to erythromycin [14]. However, nine years later in 2012, the first patient in Europe with macrolide-resistant B. pertussis was diagnosed in Lyon, France [15]. A three-week-old neonate with severe pertussis was treated repeatedly with macrolides before the detection of the resistant isolate. Of the three serial isolates from the patient, the first two were sensitive, but the third one turned to be resistant, suggesting that the B. pertussis isolate acquired the mutation leading to macrolide resistance during the macrolide treatment. Sporadic cases of macrolide-resistant B. pertussis isolates were also reported from Iran in 2009 [16].

Figure 1. Countries where B. pertussis antimicrobial susceptibility studies have been performed (created with MapChart).

In Asia, studies from Cambodia, Japan, Taiwan and Vietnam have found some macrolide-resistant B. pertussis isolates that seem to be related to resistant strains in mainland China [17,18,19]. In northern Vietnam, of NP swab samples from 184 patients with pertussis diagnosed during 2016–2020, 24 (13.0%) were found to be resistant. In Japan, the first isolation of a macrolide-resistant strain was from a 2-month-old baby in 2018. The MICs of the isolate showed >256 µg/mL for ERY and CHL and >32 µg/mL for AZT. The complete genome sequence of the macrolide resistant B. pertussis strain from Japan has been published [20]. It confirms that the isolate has a homogeneous A2047G mutation in each of the three copies of its 23S rRNA gene and that it belongs to the genotype that is common in Chinese macrolide resistant B. pertussis isolates. The issue of macrolide-resistant B. pertussis is greater and reported in more detail in China than in anywhere else in the world. The first macrolide-resistant isolates from Shandong Province in China were reported in 2011 in two asymptomatic pupils [21]. No macrolide resistance has been detected in historical isolates in China from 2008 or earlier [22,23]. More recent reports show very high prevalence of macrolide resistance among B. pertussis isolates in different parts of China (Table 1).

Table 1. Global frequencies of macrolide-resistant Bordetella pertussis.

| Country | Region/City | Year | Resistant Isolates Identified (Frequency %) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | New South Wales, Perth | 1971–2010 | 0/120 (0.0) | [24,25] |

| Cambodia | Whole country | 2017–2020 | 1/71 (1.4) | [19] |

| Canada | Ontario | 2011–2013 | 0/275 (0.0) | [26] |

| China | Xi’an | 2012–2020 | 274/299 (91.6) | [27,28,29,30,31] |

| Shandong | 2011 | 2/2 (100.0) | [21] | |

| Northern | 1970–2014 ** | 91/124 ** (91.9) | [22] | |

| Shanghai | 2016–2017 | 81/141 (57.5) | [32] | |

| Zhejiang | 2016–2020 | 271/381 (71.1) | [33,34,35] | |

| Beijing, Jinan, Nanjing, Shenzhen | 2014–2016 | 292/335 (87.2) | [36] | |

| Midwest | 2012–2015 | 163/167 (97.6) | [37] | |

| Whole country | 1950–2018 | 316/388 (81.4) | [23] | |

| Hunan | 2017–2018 | 27/55 (49.1) | [38] | |

| Shenzhen | 2015–2017 | 51/105 (48.6) | [39] | |

| Whole country | 2017–2019 | 265/311 (85.2) | [40] | |

| Czech republic | Whole country | 1967–2015 | 0/135 (0.0) | [41] |

| Finland | Whole country | 2006–2017 | 0/148 (0.0) | [42] |

| France | Bordeaux & Lyon | 2003 and 2012 | 1/41 (2.4) | [10,11] |

| Iran | Whole country | 2009–2010 | 2/11 (18.2) | [16,43] |

| Italy | Rome | 2012–2015 | 0/18 (0.0) | [44] |

| Japan | Whole country | 2017–2019 | 1/33 (3.0) | [17,19] |

| Taiwan | Whole country | 2003–2007 | 2/76 (2.6) | [19,23] |

| United Kingdom | Whole country | 2001–2009 | 0/582 (0.0) | [45] |

| United States | Colorado, Maryland, Oklahoma, Wisconsin | 1986 | 0/75 (0.0) | [46] |

| Arizona—Yuma County | 1994 | 1/1 (100.0) | [47] | |

| Utah | 1985–1997 | 1/47 (2.1) | [12] | |

| Northern California | 1998–1999 | 0/36 (0.0) | [48] | |

| Phoenix, Oakland *, San Diego | N/A *** | 1/48 (2.1) | [49] | |

| California, New York, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Illinois, Arizona, Georgia | 1994–2000 | 5/1030 **** (0.5) | [13] | |

| Minnesota | 1997–1999 | 1/8 (12.5) | [50] | |

| Vietnam | Hanoi, Ha Nam, Thai Binh | 2016–2020 | 24/184 (13.0) | [18,19] |

* Hill et al. included a control B. pertussis strain, resistant to macrolides. This strain has been isolated in Oakland but not officially published elsewhere. ** Divided into three time periods: 1970s, 2000–2008 and 2013–2014. All isolates (N = 25) collected in 1970–2008 were macrolide sensitive. *** N/A = Not available. **** Notified 5 to 7 days after incubation. Four from Arizona, one from Georgia.

Until recently, macrolide resistance in B. pertussis in China has been associated almost exclusively with the ptxP1 lineage of the bacterium [22,27,29,30,31,32,37]. However, a recent cross-sectional study describes two ptxP3 isolates from eastern China that had acquired the A2047G mutation in their 23S rRNA gene [40]. The ptxP3 lineage is currently the dominating B. pertussis circulating in most of the high-income countries that have switched to acellular pertussis vaccine in recent decades [51,52]. It has been hypothesized that the replacement of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine with co-purified acellular pertussis vaccine in the national immunization programme, the liberal use of macrolides in children with respiratory infections, and high population densities could have contributed to the effective spread of macrolide-resistant B. pertussis in China [53].

4. Mechanisms behind Macrolide Resistance in B. pertussis

Macrolide resistance can be caused by three distinct mechanisms. The most common mechanism, including for B. pertussis, is the A2047G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the 23S rRNA gene within the domain V [15,28,50]. This is equal to a SNP in position A2058G in E. coli and A2064G in M. pneumoniae [54,55]. The A2047G mutation affects the macrolide binding site in the 23S rRNA component of the 50S ribosomal subunit and prevents macrolides to inhibit the peptide elongation [50]. There are three copies of this gene in the B. pertussis genome. Bartkus et al. showed that the A2047G SNP can be found in one or more of the copies. They suggested that this mutation needs at least two copies for resistance [50]. However, many studies have shown that in most cases, all three copies are mutated among the macrolide-resistant B. pertussis strains [15,27,37].

The second possible cause is the acquisition of the ERY-resistant methylase (erm) gene, which leads to addition of methyl group in the 23S rRNA to block the ERY binding site [37,50]. However, B. pertussis do not possess this gene, which is also shown in a novel study in which 167 clinical isolates were screened to identify the possible inclusion of this gene. However, none of the strains carried such a gene [37]. So far, no studies have found this mechanism to be the cause of macrolide resistance in B. pertussis.

The third proposed mechanism is the expression of MexAB-OprM efflux pump (regulated by the mexAB-oprM operon), which helps the bacteria to regulate the uptake of macrolides. This mechanism excretes macrolide molecules out of the bacterial cell. The mechanism has been well-described and has been shown to cause resistance against many antimicrobial agents, including macrolides, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa [56]. Lately, Fong et al. described the expression of the mexAB-oprM operon within macrolide-resistant Bordetella parapertussis. Furthermore, they showed upregulation of the mexAB-oprM when B. parapertussis was grown in 256 mg/mL of ERY. As no other mechanism was found to cause the resistance, they speculated on the potential effect of this mechanism to cause the resistance. However, they also showed that this operon was not functional in B. pertussis due to deletions in mexA and oprM genes [57]. Whether there will be B. pertussis with functional mexAB-oprM operon remains to be seen.

There have only been two reports (Iran and China) where the A2047G SNP has not been the mechanism behind the macrolide resistance in B. pertussis [22,43]. However, these two studies did not perform erm gene or mexAB-oprM operon identification, and the reason for the resistance remains unknown. In the study by Mirzaei et al., the macrolide-resistant isolate was resistant to ERY/CHL but not to AZT [43]. Therefore, the presence of erm could be the cause of the resistance in these studies and would be the first one detected among macrolide-resistant B. pertussis.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antibiotics11111570

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!