Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) continues to represent a significant health care burden and its incidence is steadily increasing worldwide. Constantly evolving therapeutic options and the rarity of randomized controlled trial data to drive clinical guidelines impose challenges on physicians caring for patients with PE. PE response teams have been developed and recommended to help address these issues by facilitating a consensus among local experts while advocating the management of acute PE according to each individual patient profile.

- pulmonary embolism

- clinical pharmacology

- medicine

1. Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) represents a significant health care burden worldwide. Despite significant advances in risk stratification and management options, PE-related morbidity and mortality remain high. Ever-expanding options for catheter-based therapy and a paucity of randomized controlled trial data to inform clinical guidelines impose additional challenges on frontline clinicians caring for patients with PE. For the past decade, PE response teams have been endorsed to help address these issues by facilitating consensus among local experts while also tailoring the management of acute PE to the individual patient.

2. The Theory behind Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams

The concept of a PE response team stems from the implementation of the “heart team” approach to managing patients with urgent cardiovascular disorders such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and acute aortic syndromes [1][2]. The heart team approach plays a key role in optimizing patient selection for different treatment options, procedural performance, and follow-up care, while promoting shared decision-making [3]. Although the impact of the heart team on PE-related clinical outcomes has not been well-established yet, there are key theoretical advantages, including gathering input from a variety of clinicians, improving timeliness and coordination of care, increasing access to advanced therapies when appropriate, and presenting learning opportunities to trainees on the team [2]. Similar to multidisciplinary stroke teams, heart teams are now endorsed by guidelines that recommend their development across hospitals [1].

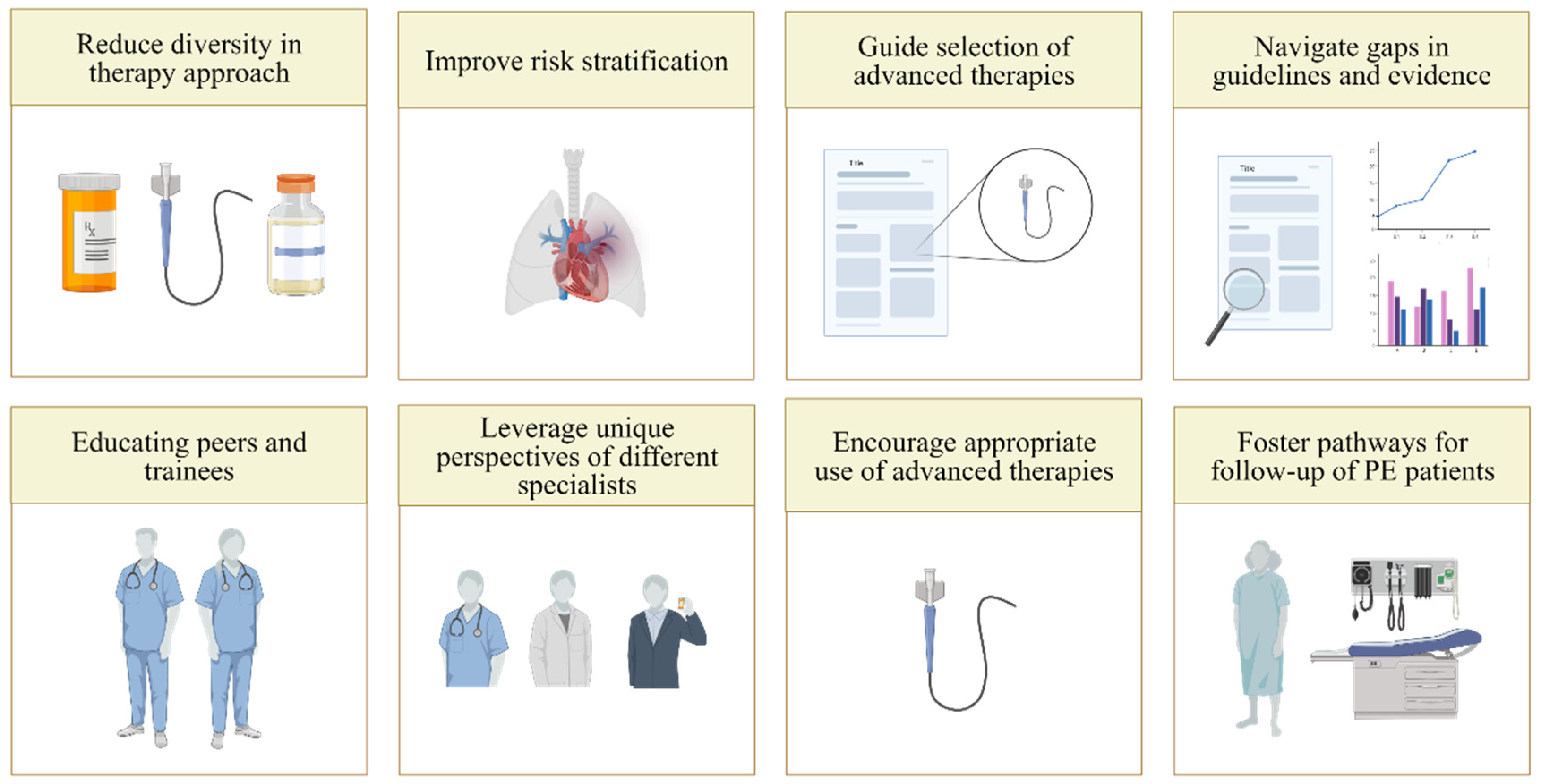

In the acute management of PE, PE response teams leverage the richness of the variety of clinicians that participate in PE diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment (Figure 1). Risk stratification, as discussed above, is a crucial but nuanced step in decision-making regarding reperfusion vs. anticoagulation alone and the type of reperfusion [1]. Navigating an increasing menu of available treatment options, especially catheter-based techniques, requires an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of each modality, as well as the individual goals of reperfusion for the specific patient, such as improving hemodynamics or gas exchange. For the long-term management of patients with acute PE, implementing these teams can help initiate appropriate follow-up so that post-discharge screening for post-PE syndrome and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension are not missed. They can also set the basis for determining the duration of anticoagulation as well as for identifying a potential underlying cause of the PE, such as thrombophilia or cancer.

Figure 1. The rationale for pulmonary embolism response teams.

3. Implementation

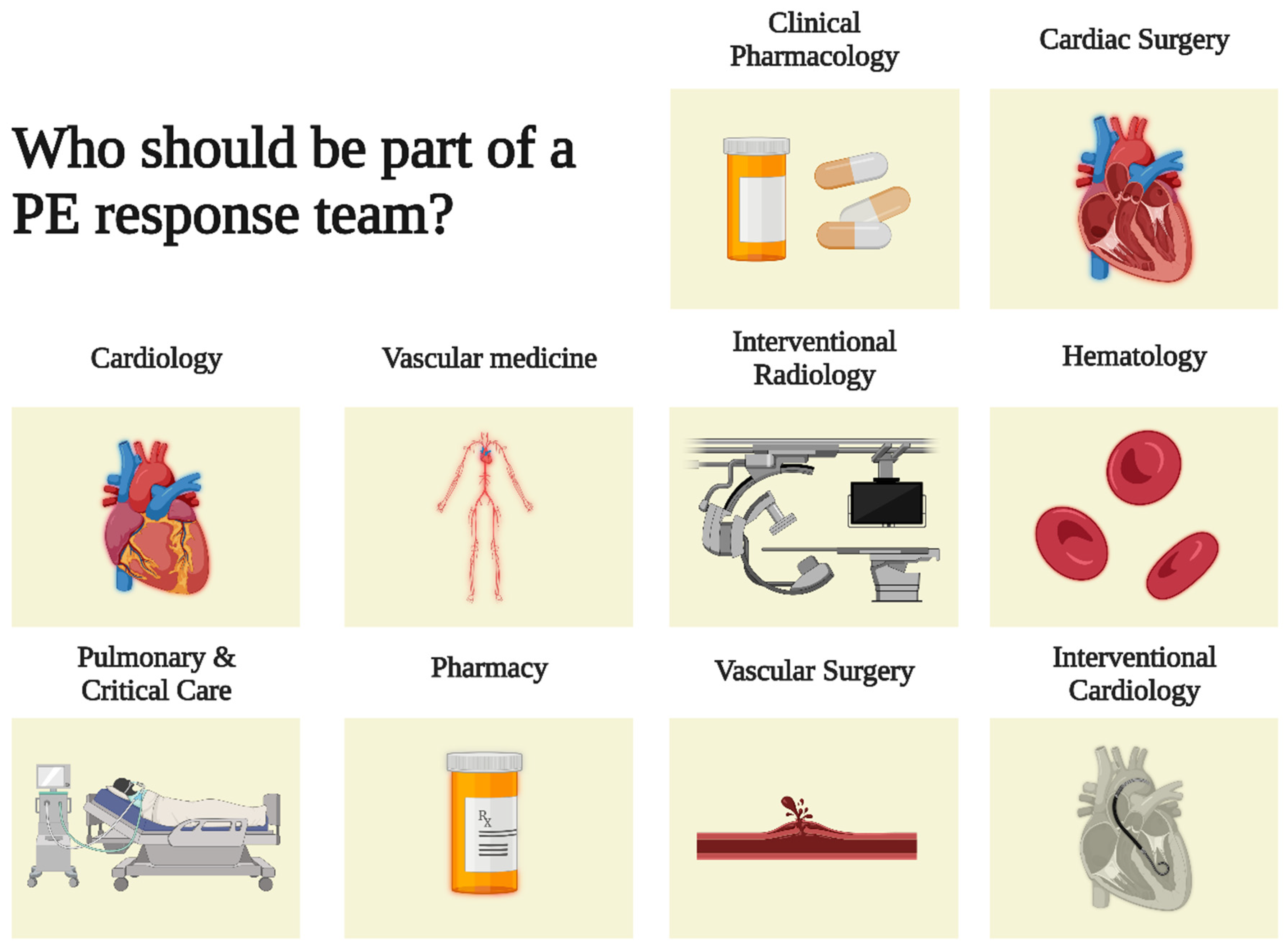

Who Should Be Part of a Pulmonary Embolism Response Team?

Various clinicians take a primary role in the care of PE in different hospitals [4]. They act and interact at different stages in the approach to patients with PE: the initial presentation, hospital management, and post-discharge follow-up. The optimal structure of a PE rapid response team remains unknown and may vary widely across institutions [5][6]. PE rapid response teams may include specialists from emergency medicine, critical care medicine, vascular medicine, cardiology, hematology, pulmonary medicine, radiology, interventional radiology, cardiac surgery, clinical pharmacology and pharmacy (Figure 2). Although PE may also be diagnosed in the inpatient setting, the initial steps in acute PE care, which involve diagnosis and risk stratification, are most often carried out in the emergency department setting [4]. After the diagnosis of PE and the assessment of imaging evidence of RV dysfunction by the emergency medicine team and radiology, the focus moves to therapeutic options for PE. Cardiology, vascular medicine, pulmonary medicine, interventional specialists, and cardiac surgery assess whether reperfusion, such as fibrinolytic treatment, catheter-based intervention, or surgery, is indicated. Endovascular interventions, such as mechanical thrombectomy and USAT, are typically provided by interventional radiology, interventional angiology, or interventional cardiology. If surgical embolectomy is warranted, it is performed by cardiac surgery. Clinical pharmacists and clinical pharmacology also play a key role in ensuring appropriate fibrinolytic dosing to optimize their efficacy and safety. Finally, patients diagnosed with PE will require long-term follow-up with either hematology, pulmonology, cardiology, or vascular medicine [7].

Figure 2. The rationale for a PE response team. PE = pulmonary embolism.

The first challenge in establishing a PE response team is the identification of a group of physicians committed to treating PE and comfortable with a shared decision-making model [8]. Because not every hospital has the same breadth of expertise, tailoring the team’s structure based on the institution’s needs and available resources is essential. Large academic hospitals may opt to include physicians-in-training, such as residents or fellows, to serve as first responders. In contrast, smaller hospitals must rely on their attending physicians and advanced practice providers for this responsibility [8]. When it comes to the appropriate team size, the number of individuals included in PE teams varies across institutions [6]. Small groups may have better team efficiency but at the expense of limiting the involvement of other interested stakeholders. On the contrary, a large group may have restricted efficiency but benefit from multidisciplinary breadth [9].

4. Structure of Pulmonary Embolism Response Team

4.1. How

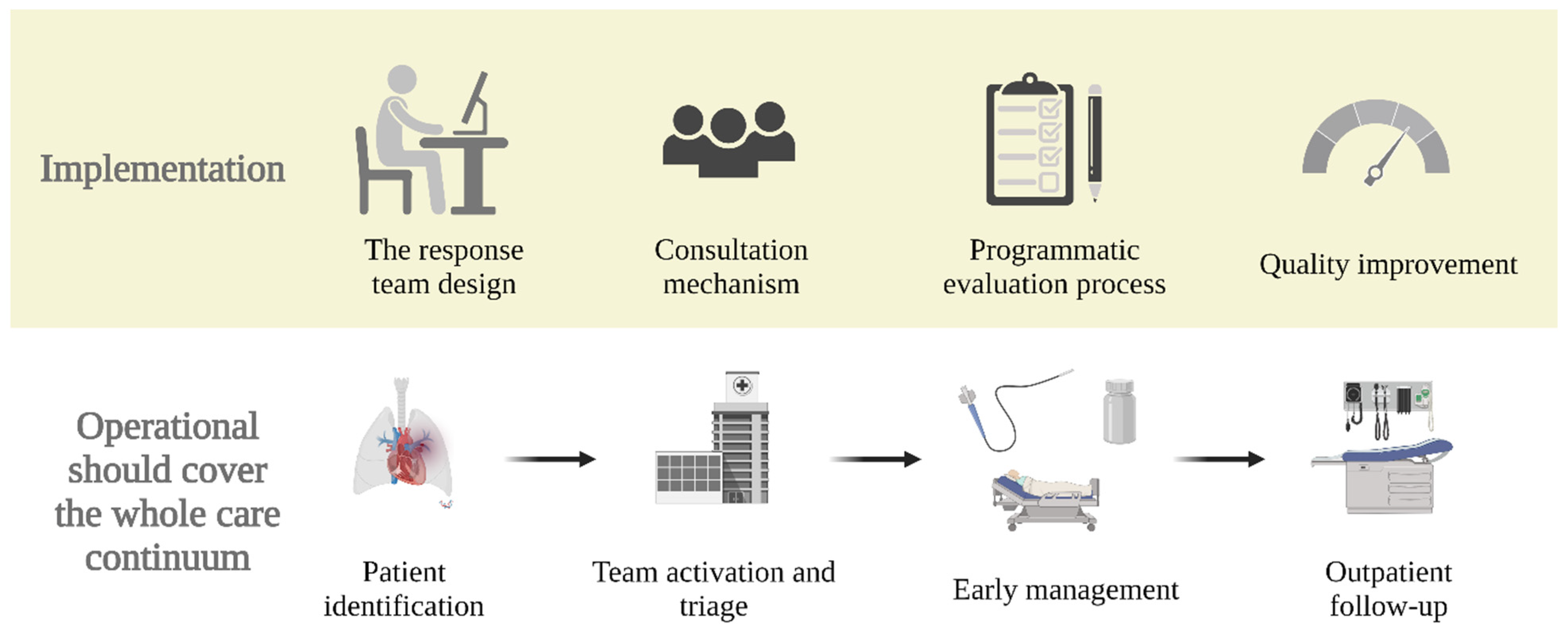

The implementation of a PE response team requires commitment of resources and personnel to establish: (1) a tailored response team design; (2) the consultation mechanism; (3) the rollout; (4) a programmatic evaluation process; and (5) mechanisms for quality improvement (Figure 3). First, in the planning and design stage, institutions need to gain support from healthcare stakeholders, identify and assemble team members, and develop protocols and algorithms to help facilitate the rapid response team operation [2]. Second, before implementation, institutions that wish to start such a team should educate all departments associated with PE care on the PE response team process, such as when and how to activate [8]. Third, institutions should iteratively assess their interdisciplinary teams’ impact, which can be conducted by reviewing cases for educational purposes and/or evaluating outcomes for quality improvement [2]. Fourth, since robust evidence assessing the outcome of this approach is lacking, institutions should also use these assessments to contribute to closing the gap in PE care research. One such strategy for improving evidence gaps in the literature is the establishment of registries and clinical trials focused on the impact of response teams [2][8]. Participation in organizations such as the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Consortium can assist hospitals who are trying to implement such teams (https://pertconsortium.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2022)). Standardized approaches or algorithms can be integrated into a PE response team to reduce some of the heterogeneity between teams while still allowing for individualized care. For example, PE response teams could integrate the European Society of Cardiology 2019 guidelines for patient and PE classification without hindering the ability of the PE response team to tailor the management as it sees fit.

Figure 3. Structure and development of a PE response team. PE = pulmonary embolism.

4.2. When and What

Operationalizing a PE response team should span the whole continuum of care, starting from patient identification, team activation, triage, early management, and outpatient follow-up. First, to minimize the number of unnecessary activations, institutions should establish a guideline for what kind of presentation should trigger the activation of the PE response team [10]. When a patient requiring consultation is identified, the PE response team is activated in real-time via a paging system [11]. Then, the patient will be rapidly evaluated, triaged, and risk stratified by a PE response team member. Subsequently, the team holds a teleconference or video conference to decide the optimal therapeutic approach according to guidelines and expert consensus. PE response teams can also assist in in-hospital follow-up; some patients may not improve or worsen initially and may require reassessment for potential advanced therapy later in the course of their admission. Lastly, patients are arranged to have a follow-up in an outpatient clinic post-discharge to ensure optimal management across the continuum of care. Patients who develop persistent PE dyspnea or functional limitation after acute PE can be more easily identified with such close follow-up. Often, the same specialists and experts would be consulted when there are concerns for post-PE syndrome or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension [12].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11206129

References

- Dudzinski, D.M.; Piazza, G. Multidisciplinary Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams. Circulation 2016, 133, 98–103.

- Kolte, D.; Parikh, S.A.; Piazza, G.; Shishehbor, M.H.; Beckman, J.A.; White, C.J.; Jaff, M.R.; Iribarne, A.; Nguyen, T.C.; Froehlich, J.B.; et al. Vascular Teams in Peripheral Vascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2477–2486.

- Holmes, D.R.; Rich, J.B.; Zoghbi, W.A.; Mack, M.J. The Heart Team of Cardiovascular Care. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 903–907.

- Rosovsky, R.; Zhao, K.; Sista, A.; Rivera-Lebron, B.; Kabrhel, C. Pulmonary embolism response teams: Purpose, evidence for efficacy, and future research directions. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 3, 315–330.

- Barnes, G.; Giri, J.; Courtney, D.M.; Naydenov, S.; Wood, T.; Rosovsky, R.; Rosenfield, K.; Kabrhel, C. Nuts and bolts of running a pulmonary embolism response team: Results from an organizational survey of the National PERT™ Consortium members. Hosp. Pract. 2017, 45, 76–80.

- Barnes, G.D.; Kabrhel, C.; Courtney, D.M.; Naydenov, S.; Wood, T.; Rosovsky, R.; Rosenfield, K.; Giri, J.; Balan, P.; Barnes, G.; et al. Diversity in the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team Model: An Organizational Survey of the National PERT Consortium Members. Chest 2016, 150, 1414–1417.

- Rosovsky, R.; Borges, J.; Kabrhel, C.; Rosenfield, K. Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: Inpatient Structure, Outpatient Follow-up, and Is It the Current Standard of Care? Clin. Chest Med. 2018, 39, 621–630.

- Channick, R.N. The Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: Why and How? Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 42, 212–217.

- Galmer, A.; Weinberg, I.; Giri, J.; Jaff, M.; Weinberg, M. The Role of the Pulmonary Embolism Response Team: How to Build One, Who to Include, Scenarios, Organization, and Algorithms. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 20, 216–223.

- Mortensen, C.S.; Kramer, A.; Schultz, J.G.; Giordano, N.; Zheng, H.; Andersen, A.; Nielsen-Kudsk, J.E.; Kabrhel, C. Predicting factors for pulmonary embolism response team activation in a general pulmonary embolism population. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2021, 53, 506–513.

- Root, C.; Dudzinski, D.; Zakhary, B.; Friedman, O.; Sista, A.; Horowitz, J. Multidisciplinary approach to the management of pulmonary embolism patients: The pulmonary embolism response team (PERT). J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2018, 11, 187–195.

- Rivera-Lebron, B.N.; Rali, P.M.; Tapson, V.F. The PERT Concept: A Step-by-Step Approach to Managing Pulmonary Embolism. Chest 2020, 159, 347–355.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!