Electron cloud densitometry is an interdisciplinary technology that uses the principles of quantum mechanics by the electron beam shifting effect. The effect is that the electron beam passing through the electron cloud, in accordance with the general principle of superposition of the system, changes its intensity in proportion to the probability density of the electron cloud. It gives direct visualization of the individual shapes of atoms, molecules and chemical bonds.

- quantum mechanics

- direct visualization

- densitometry

1. History

1.1. Philosophical Atomism

The idea that matter is made up of discrete units is a very old. Democritus (c.460–c.370 BC) called these units atoms. He taught that atoms were infinite in number, uncreated, and eternal, and that the qualities of an object result from the kind of atoms that compose it. [1][2][3]

1.2. Quantum Physical Models of Atoms

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed that all moving particles—particularly subatomic particles such as electrons—exhibit a degree of wave-like behavior. Erwin Schrödinger, fascinated by this idea, explored whether or not the movement of an electron in an atom could be better explained as a wave rather than as a particle. Schrödinger's equation, published in 1926,[4] describes an electron as a wave function instead of as a point particle. This approach elegantly predicted many of the spectral phenomena that Bohr's model failed to explain. One of its critics, Max Born, proposed instead that Schrödinger's wave function did not describe the physical extent of an electron (like a charge distribution in classical electromagnetism), but rather gave the probability that an electron would, when measured, be found at a particular point.[5] This reconciled the ideas of wave-like and particle-like electrons: the behavior of an electron, or of any other subatomic entity, has both wave-like and particle-like aspects.[6] The precise mathematical statement of the position-momentum uncertainty principle is due to Earle Hesse Kennard, Wolfgang Pauli, and Hermann Weyl.[7][8]) This invalidated Bohr's model, with its neat, clearly defined circular orbits. The modern model of the atom describes the positions of electrons in an atom in terms of probabilities. An electron can potentially be found at any distance from the nucleus, but, depending on its energy level and angular momentum, exists more frequently in certain regions around the nucleus than others; this pattern is referred to as its atomic orbital. [9] The shapes of atomic orbitals are found by solving the Schrödinger equation; however, analytic solutions of the Schrödinger equation are known for very few relatively simple model Hamiltonians including the hydrogen atom. Even the helium atom—which contains just two electrons—has defied all attempts at a fully analytic treatment.

1.3. Attempts to Visualize the Shapes of Atoms

The plum pudding model is first model of an atom shape. This model is proposed by J. J. Thomson in 1904.[12], soon after the discovery of the electron. In 1911, Ernest Rutherford, an experiment with scattering alpha particles showed that a positively charged substance is concentrated in the nucleus, which is at least 3,000 times smaller than the size of an atom. Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg and others led to the full development of quantum mechanics in the mid-1920s, which showed the rotational motion of light electrons around a heavy nucleus. Electrons fill the entire volume of the atom. In this regard, Richard Feynman[13]proposed to consider an atom in the form of a cloud, whose electron cloud density is proportional to the probability density for observing the electron. Thus “picture” of an atom is a nucleus surrounded by an “electron cloud”.

2. Electron Cloud Density of Atoms, Molecules and Chemical Bonds

In its efforts to learn as much as possible about nature, modern physics has found that electron clouds can be “known” with certainty. Direct visualization of individual electron cloud was obtained in 2018 Olexandr P. Kucherov a physicist from Ukraine .[17] Direct visualization of small objects studied by chemistry is made possible by the discovery of the electron beam shifting in accordance with the electron cloud density. Accordance with this effect, an atom begins to illuminate, depicting its own form! A quantum mechanical theory of the effect is given. As a result, it was possible to trace a chemical reaction with a change in the chemical bonds, geometry molecules, and distances between atoms.

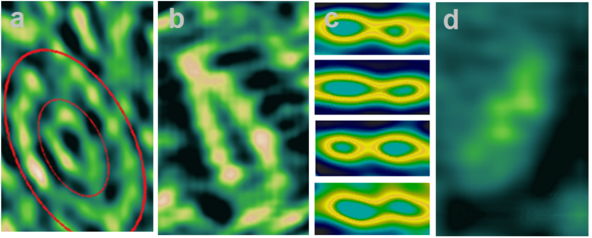

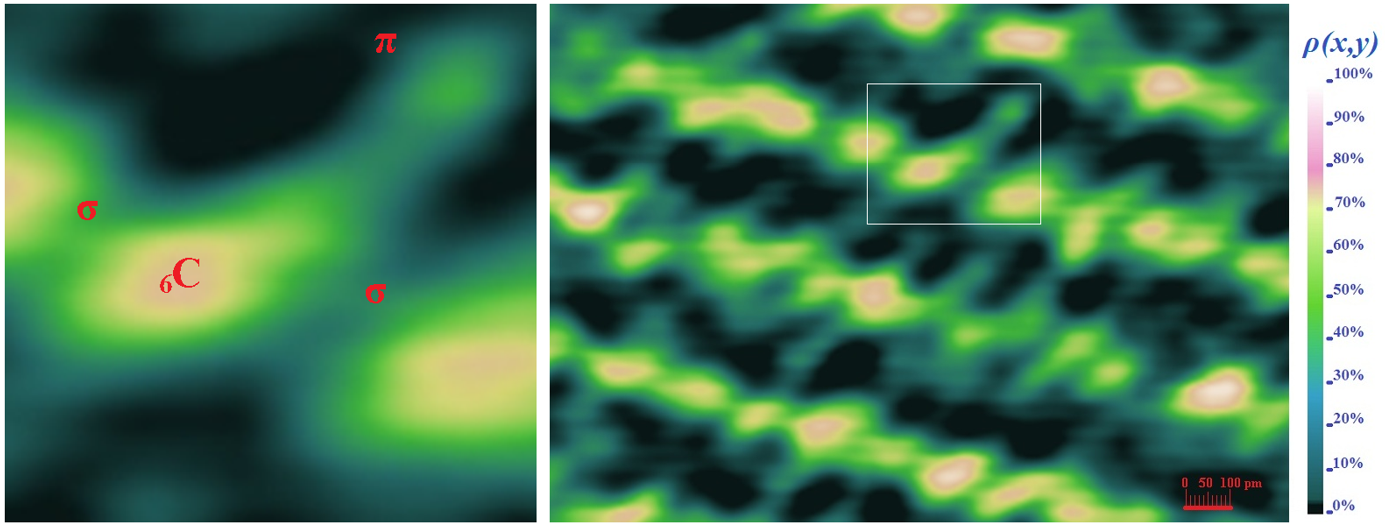

3. Electron Cloud Density of an Individual Carbon Atom

Electron cloud densitometry was used to visualize crystalline graphite along with internal orbitals and valence electrons. Photo on the left shows how six electrons form a complex shape of a carbon atom 6C. Tow core electrons create pink sphere in the center. One valence electron forms weak π bond (blue) and three valence electrons form strong σ bonds sp² orbital hybrids left, right (green) and behind from the center of the carbon atom. The color scale of the electron cloud density ρ(x,y) is given as a percentage. A space around the atom is mostly black because there is zero density of the electron cloud.

Photo on the right shows crystalline carbon where the atoms (pink spheres) are arranged in layers that are connected by strong σ bonds sp² orbital hybrids (green), while the weak π bonds (blue) extend between the layers.

4. Quantum Mechanics Theory of the Electron Beam Shifting Effect

In the mathematically rigorous formulation of quantum mechanics, the state of a quantum mechanical system is a wave function Ψ. The wave function Ψ12(q1,q2) with coordinates q1,q2, describes the state of a composite systems consisting of en electron cloud of the testing sample Ψ1(q1) and plane wave of the electron beam which propagates along the axis z:

Ψ2(z) = √j exp (ikz) ,

where j – electron beam density; k - constant for a plane wave. Respectively, the screen of the electron densitometer is in the plane x,y.

According to quantum superposition, the wave function of the composite systems is the product of these two wave functions:

Ψ12(q1,q2) = Ψ1(q1) √j exp (ikz).

The probability ρ (x, y) to find an electron at the point x,y of the densitometer screen is the integral over all the coordinates of the plane wave and the coordinate z of the wave function of the electrons of the atom:

ρ (x, y) = ʃ Ψ12(q1,q2) Ψ*12(q1,q2) dq1dz.

The integral over the coordinates dq1 of a plane wave is equal to j, the square of the modulus. Under the integral remains the density of the electron cloud:

ρ(x, y) = jnʃρ(x,y,z) dz,

where ρ (x, y, z) is the probability of finding an electron in the volume dx, dy, dz of an atom which satisfies the normalization condition:

1 = ʃʃʃρ(x,y,z) dx, dy, dz.

Note that the normalization condition must be satisfied for each of the n electrons in the atom. Finally, the relationship between the intensity of the electron beam and the density of the electron cloud at the point x, y takes the form:

I (x, y) = jnρ(x,y),

where n is the number of electrons in the atom.[18]

As a result, the intensity of the electron beam passing through the electron cloud of the testing sample at the point x, y is directly proportional to the density of the electron cloud in the column at that point. It is the essence of the electron beam shifting effect.

The expression was obtained in general on the basis of quantum mechanics. The integral of the wave functions found from the Schrödinger equation and the superposition principle was taken.

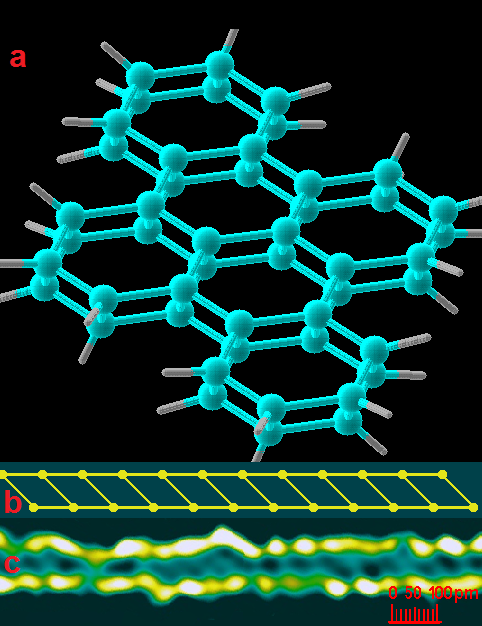

5. Application

Electron cloud densitometry makes it possible to study in some detail the mutual arrangement of atoms in a molecule and the shape of chemical bonds, as well as to follow the ways in which chemical reactions take place. As a result of the use of electron cloud densitometry, Rudenite was found, which is a superdense allotropic form carbon with a two-layer diamond-like structure[15] whose existence was later confirmed by an independent group of scientists.[19] Subsequently, by electron cloud densitometry, this substance was synthesized in an amount sufficient for laboratory studies[18]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Physics:Electron_cloud_densitometry

References

- Kenny, Anthony (2004). Ancient Philosophy. A New History of Western Philosophy. 1. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–28. ISBN 0-19-875273-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=cpYUDAAAQBAJ&q=Democritus.

- Pyle, Andrew (2010). "Atoms and Atomism". in Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W.; Settis, Salvatore. The Classical Tradition. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-0-674-03572-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=LbqF8z2bq3sC&q=Atoms.

- Cohen, Henri; Lefebvre, Claire, eds (2017). Handbook of Categorization in Cognitive Science (Second ed.). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-08-101107-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=zIrCDQAAQBAJ&q=Leucippus+Democritus+atom&pg=PA427.

- Schrödinger, Erwin (1926). "Quantisation as an Eigenvalue Problem". Annalen der Physik 81 (18): 109–139. doi:10.1002/andp.19263861802. Bibcode: 1926AnP...386..109S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fandp.19263861802

- Mahanti, Subodh. "Max Born: Founder of Lattice Dynamics". http://www.vigyanprasar.gov.in/scientists/MBorn.htm.

- Greiner, Walter (4 October 2000). "Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction". ISBN 9783540674580. https://books.google.com/books?id=7qCMUfwoQcAC&q=wave-particle+all-particles&pg=PA29.

- Busch, Paul; Lahti, Pekka; Werner, Reinhard F. (17 October 2013). "Proof of Heisenberg's Error-Disturbance Relation" (in en). Physical Review Letters 111 (16): 160405. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.160405. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 24182239. Bibcode: 2013PhRvL.111p0405B. https://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.111.160405

- Appleby, David Marcus (6 May 2016). "Quantum Errors and Disturbances: Response to Busch, Lahti and Werner" (in en). Entropy 18 (5): 174. doi:10.3390/e18050174. Bibcode: 2016Entrp..18..174A. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fe18050174

- Milton Orchin; Roger Macomber; Allan Pinhas; R. Wilson. "The Vocabulary and Concepts of Organic Chemistry, Second Edition". http://media.wiley.com/product_data/excerpt/81/04716802/0471680281.pdf.

- Tipler, P. A.; Mosca, G. (2008). Physics for Scientists and Engineers – with Modern Physics (6th ed.). Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-8964-2.

- Heitler, W.; London, F. (1927). "Wechselwirkung neutraler Atome und homoopolare Bindung nach der Quantenmechanik". Zeitschrift für Physik 44 (6–7): 455–472. doi:10.1007/bf01397394. Bibcode: 1927ZPhy...44..455H. English translation in Hettema, H. (2000). Quantum Chemistry: Classic Scientific Papers. World Scientific. pp. 140. ISBN 978-981-02-2771-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=qsidHRJmUoIC. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- "Plum Pudding Model". Universe Today. 27 August 2009. http://www.universetoday.com/38326/plum-pudding-model/.

- Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew (2006). The Feynman Lectures on Physics -The Definitive Edition, Vol 1 lect 6. Pearson PLC, Addison Wesley. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8053-9046-9.

- Kucherov, O. P.; Lavrovsky, S.E. (2017). "Electron Trajectory Shifting Effect". Abstract Book. International Research and Practice Conference: NANOTECNOLOGY AND NANO-MATERIALSE (NANO-2017): 491. http://www.iop.kiev.ua/~nano2017/files/abstracts/Kucherov.pdf.

- Rud, Alexander D.; Kornienko, Nikolay E.; Kirian, Inna M.; Kirichenko, Alexey N; Kucherov, O. P. (2018). "Local heteroallotropic structures of carbon". Materials Today: Proceedings 5 (12): 26089–26095. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2018.08.035. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.matpr.2018.08.035

- Kucherov, O. P. (2021). "Direct Visualization of Covalent Chemical Bonds in Crystalline Silicon". American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) 10 (6): 54–58.

- Patent UA115602 – The method for obtaining an image with a sub-diffraction resolution and an opto-electronic system for its implementation https://uapatents.com/?search=115602&type=number

- Kucherov, O. P.; Rud, A.D. (2018). "Direct visualization of individual molecules in molecular crystals by electron cloud densitometry". Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals 674 (1): 40–47. doi:10.1080/15421406.2019.1578510. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F15421406.2019.1578510

- Gao, Yang; Cao, Tengfei; Cellini, Filippo; Berger, Claire; de Heer, Walter A.; Tosatti, Erio; Riedo, Elisa; Bongiorno, Angelo (2018). "Ultrahard carbon film from epitaxial two-layer graphene". Nature Nanotechnology 13 (2): 133–138. doi:10.1038/s41565-017-0023-9. PMID 29255290. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fs41565-017-0023-9