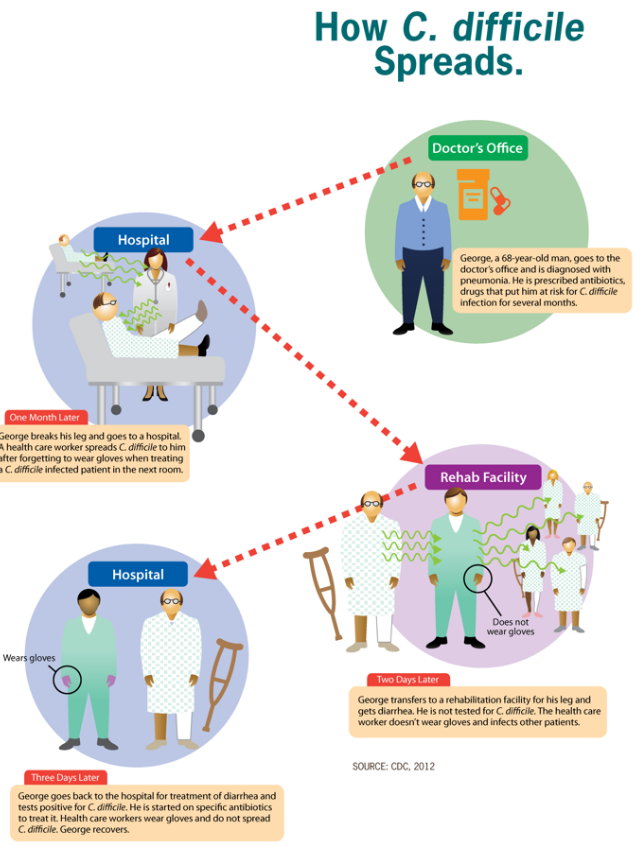

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI or C-dif) is a symptomatic infection due to the spore-forming bacterium, Clostridium difficile. Symptoms include watery diarrhea, fever, nausea, and abdominal pain. It makes up about 20% of cases of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Complications may include pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, perforation of the colon, and sepsis. Clostridium difficile infection is spread by bacterial spores found within feces. Surfaces may become contaminated with the spores with further spread occurring via the hands of healthcare workers. Risk factors for infection include antibiotic or proton pump inhibitors use, hospitalization, other health problems, and older age. Diagnosis is by stool culture or testing for the bacteria's DNA or toxins. If a person tests positive but has no symptoms, the condition is known as C. difficile colonization rather than an infection. Prevention is by hand washing, terminal room cleaning in hospital, and limiting antibiotic use. Discontinuation of antibiotics may result in resolution of symptoms within three days in about 20% of those infected. Often the antibiotics metronidazole, vancomycin or fidaxomicin will cure the infection. Retesting after treatment, as long as the symptoms have resolved, is not recommended, as the person may remain colonized. Recurrences have been reported in up to 25% of people. Some tentative evidence indicates fecal microbiota transplantation and probiotics may decrease the risk of recurrence. C. difficile infections occur in all areas of the world. About 453,000 cases occurred in the United States in 2011, resulting in 29,000 deaths. Rates of disease globally have increased between 2001 and 2016. Women are more often affected than men. The bacterium was discovered in 1935 and found to be disease-causing in 1978. In the United States, health–care associated infections increase the cost of care by US$1.5 billion each year.

- fecal microbiota

- metronidazole

- difficile

1. Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of CDI range from mild diarrhea to severe life-threatening inflammation of the colon.[1]

In adults, a clinical prediction rule found the best signs to be significant diarrhea ("new onset of more than three partially formed or watery stools per 24-hour period"), recent antibiotic exposure, abdominal pain, fever (up to 40.5 °C or 105 °F), and a distinctive foul odor to the stool resembling horse manure.[2] In a population of hospitalized patients, prior antibiotic treatment plus diarrhea or abdominal pain had a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 45%.[3] In this study with a prevalence of positive cytotoxin assays of 14%, the positive predictive value was 18% and the negative predictive value was 94%.

In children, the most prevalent symptom of a CDI is watery diarrhea with at least three bowel movements a day for two or more days, which may be accompanied by fever, loss of appetite, nausea, and/or abdominal pain.[4] Those with a severe infection also may develop serious inflammation of the colon and have little or no diarrhea.

2. Cause

Infection with C. difficile bacteria are responsible for C. difficile diarrhea.

2.1. C. difficile

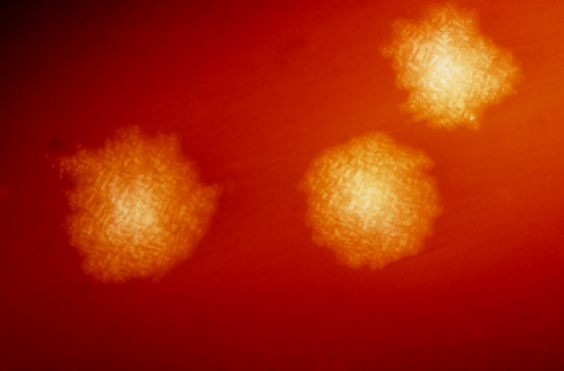

Clostridia are anaerobic motile bacteria, ubiquitous in nature, and especially prevalent in soil. Under the microscope, they appear as long, irregular (often drumstick- or spindle-shaped) cells with a bulge at their terminal ends. Under Gram staining, C. difficile cells are Gram-positive and show optimum growth on blood agar at human body temperatures in the absence of oxygen. When stressed, the bacteria produce spores that are able to tolerate extreme conditions that the active bacteria cannot tolerate.[5]

C. difficile may become established in the human colon; it is present in 2–5% of the adult population.[5]

Pathogenic C. difficile strains produce multiple toxins.[6] The most well-characterized are enterotoxin (Clostridium difficile toxin A) and cytotoxin (Clostridium difficile toxin B), both of which may produce diarrhea and inflammation in infected patients, although their relative contributions have been debated.[5] Toxins A and B are glucosyltransferases that target and inactivate the Rho family of GTPases. Toxin B (cytotoxin) induces actin depolymerization by a mechanism correlated with a decrease in the ADP-ribosylation of the low molecular mass GTP-binding Rho proteins.[7] Another toxin, binary toxin, also has been described, but its role in disease is not fully understood.[8]

Antibiotic treatment of CDIs may be difficult, due both to antibiotic resistance and physiological factors of the bacteria (spore formation, protective effects of the pseudomembrane).[5] The emergence of a new and highly toxic strain of C. difficile that is resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, said to be causing geographically dispersed outbreaks in North America, was reported in 2005.[9] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta warned of the emergence of an epidemic strain with increased virulence, antibiotic resistance, or both.[10]

C. difficile is transmitted from person to person by the fecal-oral route. The organism forms heat-resistant spores that are not killed by alcohol-based hand cleansers or routine surface cleaning. Thus, these spores survive in clinical environments for long periods. Because of this, the bacteria may be cultured from almost any surface. Once spores are ingested, their acid-resistance allows them to pass through the stomach unscathed. Upon exposure to bile acids, they germinate and multiply into vegetative cells in the colon.

In 2005, molecular analysis led to the identification of the C. difficile strain type characterized as group BI by restriction endonuclease analysis, as North American pulse-field-type NAP1 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and as ribotype 027; the differing terminology reflects the predominant techniques used for epidemiological typing. This strain is referred to as C. difficile BI/NAP1/027.[11]

2.2. Risk Factors

Antibiotics

C. difficile colitis is associated most strongly with the use of these antibiotics: fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and clindamycin.[12]

Some research suggests the routine use of antibiotics in the raising of livestock is contributing to outbreaks of bacterial infections such as C. difficile.[13]

Healthcare environment

People are most often infected in hospitals, nursing homes,[14] or other medical institutions, although infection outside medical settings is increasing. Individuals can develop the infection if they touch objects or surfaces that are contaminated with feces and then touch their mouth or mucous membranes. Healthcare workers could possibly spread the bacteria to patients or contaminate surfaces through hand contact.[15] The rate of C. difficile acquisition is estimated to be 13% in patients with hospital stays of up to two weeks, and 50% with stays longer than four weeks.[16]

Long-term hospitalization or residence in a nursing home within the previous year are independent risk factors for increased colonization.[17]

Acid suppression medication

Increasing rates of community-acquired CDI are associated with the use of medication to suppress gastric acid production: H2-receptor antagonists increased the risk 1.5-fold, and proton pump inhibitors by 1.7 with once-daily use and 2.4 with more than once-daily use.[18][19]

Elemental diet

As a result of suppression of healthy bacteria, via a loss of bacterial food source, prolonged use of an elemental diet elevates the risk of developing C. difficile infection.[20]

3. Pathophysiology

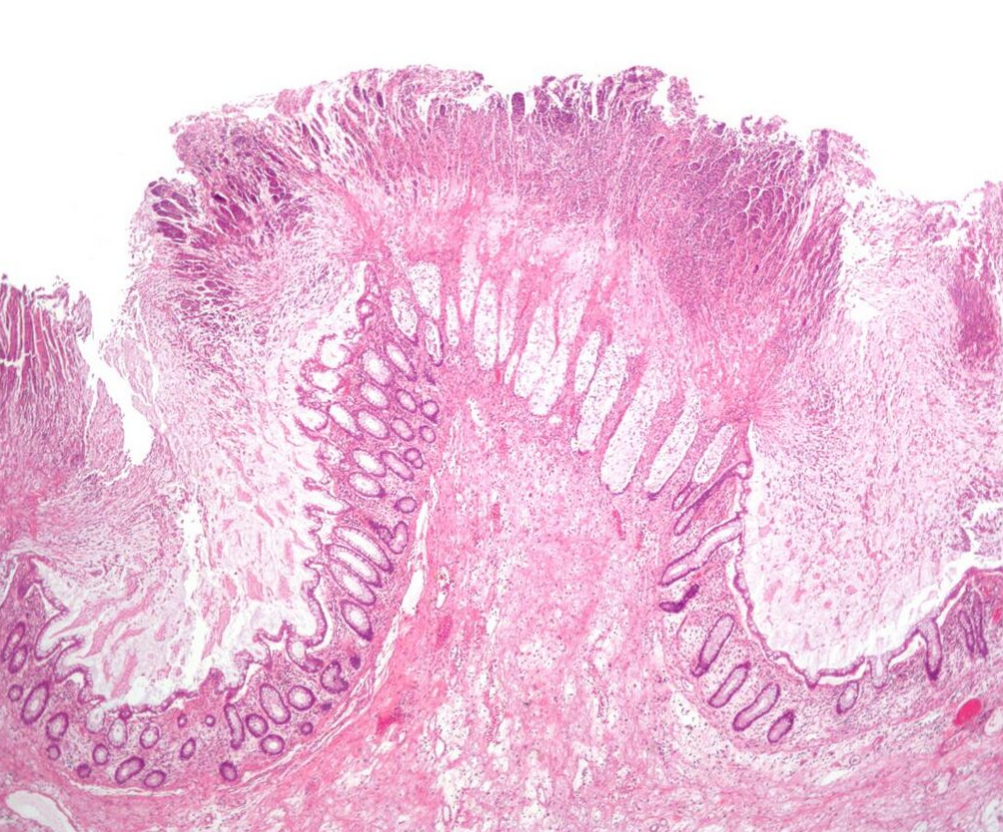

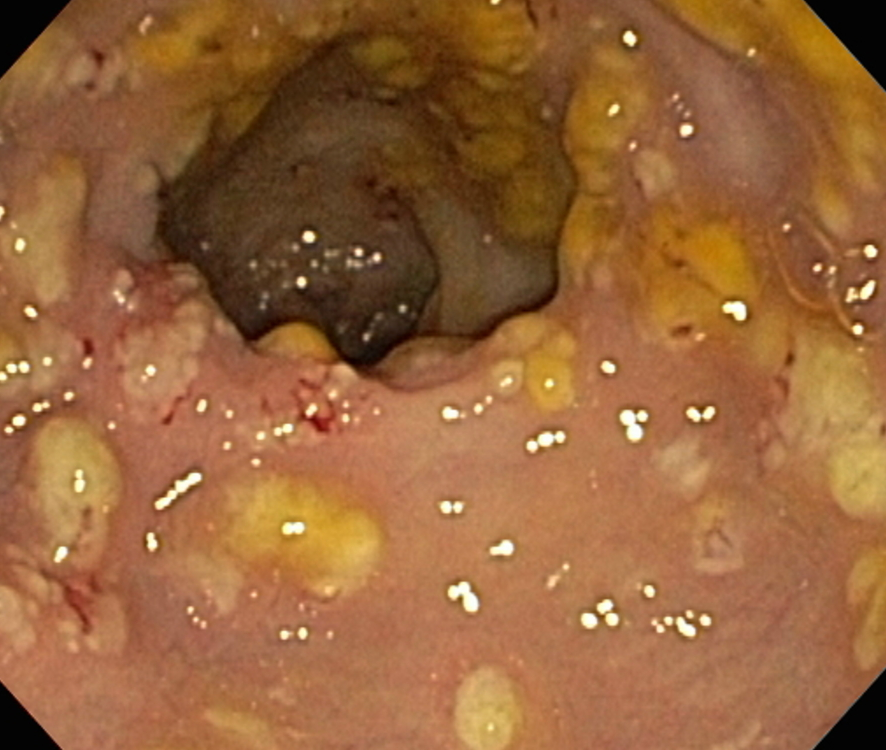

The use of systemic antibiotics, including any penicillin-based antibiotic such as ampicillin, cephalosporins, and clindamycin, causes the normal microbiota of the bowel to be altered. In particular, when the antibiotic kills off other competing bacteria in the intestine, any bacteria remaining will have less competition for space and nutrients. The net effect is to permit more extensive growth than normal of certain bacteria. C. difficile is one such type of bacterium. In addition to proliferating in the bowel, C. difficile also produces toxins. Without either toxin A or toxin B, C. difficile may colonize the gut, but is unlikely to cause pseudomembranous colitis.[21] The colitis associated with severe infection is part of an inflammatory reaction, with the "pseudomembrane" formed by a viscous collection of inflammatory cells, fibrin, and necrotic cells.[5]

4. Diagnosis

Prior to the advent of tests to detect C. difficile toxins, the diagnosis most often was made by colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. The appearance of "pseudomembranes" on the mucosa of the colon or rectum is highly suggestive, but not diagnostic of the condition.[22] The pseudomembranes are composed of an exudate made of inflammatory debris, white blood cells. Although colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are still employed, now stool testing for the presence of C. difficile toxins is frequently the first-line diagnostic approach. Usually, only two toxins are tested for—toxin A and toxin B—but the organism produces several others. This test is not 100% accurate, with a considerable false-negative rate even with repeat testing.

4.1. Cytotoxicity Assay

C. difficile toxins have a cytopathic effect in cell culture, and neutralization of any effect observed with specific antisera is the practical gold standard for studies investigating new CDI diagnostic techniques.[5] Toxigenic culture, in which organisms are cultured on selective media and tested for toxin production, remains the gold standard and is the most sensitive and specific test, although it is slow and labor-intensive.[23]

4.2. Toxin ELISA

Assessment of the A and B toxins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for toxin A or B (or both) has a sensitivity of 63–99% and a specificity of 93–100%.

Previously, experts recommended sending as many as three stool samples to rule out disease if initial tests are negative, but evidence suggests repeated testing during the same episode of diarrhea is of limited value and should be discouraged.[24] C. difficile toxin should clear from the stool of previously infected patients if treatment is effective. Many hospitals only test for the prevalent toxin A. Strains that express only the B toxin are now present in many hospitals, however, so testing for both toxins should occur.[25][26] Not testing for both may contribute to a delay in obtaining laboratory results, which is often the cause of prolonged illness and poor outcomes.

4.3. Other Stool Tests

Stool leukocyte measurements and stool lactoferrin levels also have been proposed as diagnostic tests, but may have limited diagnostic accuracy.[27]

4.4. PCR

Testing of stool samples by real-time polymerase chain reaction is able to detect C. difficile about 93% of the time and when positive is incorrectly positive about 3% of the time.[28] This is more accurate than cytotoxigenic culture or cell cytotoxicity assay.[28] Other benefits are that the result can be achieved within three hours.[28] Drawbacks include a higher cost and the fact that the test only looks for the gene for the toxin and not the toxin itself.[28] The later means that if the test is used without confirmation, overdiagnosis may occur.[28] Repeat testing may be misleading, and testing specimens more than once every seven days in people without new symptoms is highly unlikely to yield useful information.[29]

5. Prevention

Self containment by housing people in private rooms is important to prevent the spread of C. difficile between patients.[30] Contact precautions are an important part of preventing the spread of C. difficile. C. difficile does not often occur in people who are not taking antibiotics so limiting use of antibiotics decreases the risk.[31]

5.1. Antibiotics

The most effective method for preventing CDI is proper antimicrobial prescribing. In the hospital setting, where CDI is most common, nearly all patients who develop CDI are exposed to antimicrobials. Although proper antimicrobial prescribing is highly recommended, about 50% of antimicrobial use is considered inappropriate. This is consistent whether in the hospital, clinic, community, or academic setting. A decrease in CDI by limiting antibiotics or by limiting unnecessary antimicrobial prescriptions in general, both in an outbreak and nonoutbreak setting has been demonstrated to be most strongly associated with reduced CDI. Further, reactions to medication may be severe: CDI infections were the most common contributor to adverse drug events seen in U.S. hospitals in 2011.[32] In some regions of the UK, reduced used of fluoroquinolone antibiotics seems to lead to reduced rates of CDI.[33]

5.2. Probiotics

Some evidence indicates probiotics may be useful to prevent infection and recurrence.[34][35] Treatment with Saccharomyces boulardii in those who are not immunocompromised with C. difficile also may be useful.[36][37] Initially, in 2010, the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommended against their use due to the risk of complications.[34][36] Subsequent reviews, however, did not find an increase in adverse effects with treatment,[35] and overall treatment appears safe.[38]

5.3. Infection Control

Rigorous infection protocols are required to minimize this risk of transmission.[39] Infection control measures, such as wearing gloves and noncritical medical devices used for a single person with CDI, are effective at prevention.[40] This works by limiting the spread of C. difficile in the hospital setting. In addition, washing with soap and water will eliminate the spores from contaminated hands, but alcohol-based hand rubs are ineffective.[41] These precautions should remain in place among those in hospital for at least 2 days after the diarrhea has stopped.[42]

Bleach wipes containing 0.55% sodium hypochlorite have been shown to kill the spores and prevent transmission between patients.[43] Installing lidded toilets and closing the lid prior to flushing also reduces the risk of contamination.[44]

Those who have CDIs should be in rooms with other people with CDIs or by themselves when in hospital.[40]

Common hospital disinfectants are ineffective against C. difficile spores, and may promote spore formation, but disinfectants containing a 10:1 ratio of water to bleach effectively kill the spores.[45] Hydrogen peroxide vapor (HPV) systems used to sterilize a patient room after discharge have been shown to reduce infection rates and to reduce risk of infection to subsequent patients. The incidence of CDI was reduced by 53%[46] or 42%[47] through use of HPV. Ultraviolet cleaning devices and housekeeping staff especially dedicated to disinfecting the rooms of patients infected with C. difficile after discharge may be effective.[48]

6. Treatment

Carrying C. difficile without symptoms is common. Treatment in those without symptoms is controversial. In general, mild cases do not require specific treatment.[5][49] Oral rehydration therapy is useful in treating dehydration associated with the diarrhea.

6.1. Medications

Several different antibiotics are used for C. difficile, with the available agents being more or less equally effective.[50]

- Vancomycin or fidaxomicin are the typically recommended for mild, moderate, and severe infections.[51] They are also the first-line treatment for pregnant women, especially since metronidazole may cause birth defects.[52] Typical vancomycin is taken four times a day by mouth for 10 days.[52] It may also be given rectally if the person develops an ileus.[51]

- Fidaxomicin has been found to be as effective as vancomycin in those with mild to moderate disease, and may be better in those with severe disease.[49][53] It is tolerated as well as vancomycin,[54] and may have a lower risk of recurrence.[50] It may be used in those who have recurrent infections and have not responded to other antibiotics.[53]

- Metronidazole is an alternative treatment for non severe C. difficile infections.[51] It may also be used intravenously together with vancomycin in those with very severe disease.[51]

Medications used to slow or stop diarrhea, such as loperamide, have been thought to have the potential to worsen C. difficile disease, so are not generally recommended.[55] Evidence to support worse outcomes with use however is poor.[56] Cholestyramine, an ion exchange resin, is effective in binding both toxin A and B, slowing bowel motility, and helping prevent dehydration.[57] Cholestyramine is recommended with vancomycin. A last-resort treatment in those who are immunosuppressed is intravenous immunoglobulin.[57]

6.2. Probiotics

Evidence to support the use of probiotics in the treatment of active disease is insufficient.[36][58] Thus in this situation, they are recommended neither as an add-on to standard therapy nor for use alone.[59]

6.3. Stool Transplant

Fecal bacteriotherapy, also known as a stool transplant, is roughly 85% to 90% effective in those for whom antibiotics have not worked.[60][61] It involves infusion of the microbiota acquired from the feces of a healthy donor to reverse the bacterial imbalance responsible for the recurring nature of the infection.[62] The procedure replenishes the normal colonic microbiota that had been wiped out by antibiotics, and re-establishes resistance to colonization by Clostridium difficile.[63] Side effects, at least initially, are few.[61]

Some evidence looks hopeful that fecal transplant can be delivered in the form of a pill.[64] They are available in the United States, but are not FDA-approved as of 2015.[65]

6.4. Surgery

In those with severe C. difficile colitis, colectomy may improve the outcomes.[66] Specific criteria may be used to determine who will benefit most from surgery.[67]

7. Prognosis

After a first treatment with metronidazole or vancomycin, C. difficile recurs in about 20% of people. This increases to 40% and 60% with subsequent recurrences.[68]

8. Epidemiology

C. difficile diarrhea is estimated to occur in eight of 100,000 people each year.[69] Among those who are admitted to hospital, it occurs in between four and eight people per 1,000.[69] In 2011, it resulted in about half a million infections and 29,000 deaths in the United States.[70]

Due in part to the emergence of a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain, C. difficile-related deaths increased 400% between 2000 and 2007 in the United States.[71] According to the CDC, "C. difficile has become the most common microbial cause of healthcare-associated infections in U.S. hospitals and costs up to $4.8 billion each year in excess health care costs for acute care facilities alone."[72]

9. History

Initially named Bacillus difficilis by Hall and O'Toole in 1935 because it was resistant to early attempts at isolation and grew very slowly in culture, it was renamed in 1970.[68][73]

Pseudomembranous colitis first was described as a complication of C. difficile infection in 1978,[74] when a toxin was isolated from patients suffering from pseudomembranous colitis and Koch's postulates were met.

9.1. Notable Outbreaks

- On 4 June 2003, two outbreaks of a highly virulent strain of this bacterium were reported in Montreal, Quebec, and Calgary, Alberta. Sources put the death count to as low as 36 and as high as 89, with around 1,400 cases in 2003 and within the first few months of 2004. CDIs continued to be a problem in the Quebec healthcare system in late 2004. As of March 2005, it had spread into the Toronto area, hospitalizing 10 people. One died while the others were being discharged.

- A similar outbreak took place at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in the United Kingdom between 2003 and 2005. The local epidemiology of C. difficile may offer clues on how its spread may relate to the time a patient spends in hospital and/or a rehabilitation center. It also samples the ability of institutions to detect increased rates, and their capacity to respond with more aggressive hand-washing campaigns, quarantine methods, and the availability of yogurt containing live cultures to patients at risk for infection.

- Both the Canadian and English outbreaks possibly were related to the seemingly more virulent strain NAP1/027 of the bacterium. Known as Quebec strain, it has been implicated in an epidemic at two Dutch hospitals (Harderwijk and Amersfoort, both 2005). A theory for explaining the increased virulence of 027 is that it is a hyperproducer of both toxins A and B and that certain antibiotics may stimulate the bacteria to hyperproduce.

- On 1 October 2006, C. difficile was said to have killed at least 49 people at hospitals in Leicester, England , over eight months, according to a National Health Service investigation. Another 29 similar cases were investigated by coroners.[75] A UK Department of Health memo leaked shortly afterward revealed significant concern in government about the bacterium, described as being "endemic throughout the health service"[76]

- On 27 October 2006, nine deaths were attributed to the bacterium in Quebec.[77]

- On 18 November 2006, the bacterium was reported to have been responsible for 12 deaths in Quebec. This 12th reported death was only two days after the St. Hyacinthe's Honoré Mercier announced the outbreak was under control. Thirty-one patients were diagnosed with CDIs. Cleaning crews took measures in an attempt to clear the outbreak.[78]

- C. difficile was mentioned on 6,480 death certificates in 2006 in UK.[79]

- On 27 February 2007, a new outbreak was identified at Trillium Health Centre in Mississauga, Ontario, where 14 people were diagnosed with CDIs. The bacteria were of the same strain as the one in Quebec. Officials have not been able to determine whether C. difficile was responsible for deaths of four patients over the prior two months.[80]

- Between February and June 2007, three patients at Loughlinstown Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, were found by the coroner to have died as a result of C. difficile infection. In an inquest, the Coroner's Court found the hospital had no designated infection control team or consultant microbiologist on staff.[81]

- Between June 2007 and August 2008, Northern Health and Social Care Trust Northern Ireland, Antrim Area, Braid Valley, Mid Ulster Hospitals were the subject of inquiry. During the inquiry, expert reviewers concluded that C. difficile was implicated in 31 of these deaths, as the underlying cause in 15, and as a contributory cause in 16. During that time, the review also noted 375 instances of CDIs in patients.[82]

- In October 2007, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust was heavily criticized by the Healthcare Commission regarding its handling of a major outbreak of C. difficile in its hospitals in Kent from April 2004 to September 2006. In its report, the Commission estimated approximately 90 patients "definitely or probably" died as a result of the infection.[83][84]

- In November 2007, the 027 strain spread into several hospitals in southern Finland, with 10 deaths out of 115 infected patients reported on 2007-12-14.[85]

- In November 2009, four deaths at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Ireland have possible links to CDI. A further 12 patients tested positive for infection, and another 20 showed signs of infection.[86]

- From February 2009 to February 2010, 199 patients at Herlev hospital in Denmark were suspected of being infected with the 027 strain. In the first half of 2009, 29 died in hospitals in Copenhagen after they were infected with the bacterium.[87]

- In May 2010, a total of 138 patients at four different hospitals in Denmark were infected with the 027 strain [88] plus there were some isolated occurrences at other hospitals.[89]

- In May 2010, 14 fatalities were related to the bacterium in the Australian state of Victoria. Two years later, the same strain of the bacterium was detected in New Zealand.[90]

- On 28 May 2011, an outbreak in Ontario had been reported, with 26 fatalities as of 24 July 2011.[91]

- In 2012/2013, a total of 27 people at one hospital in the south of Sweden (Ystad) were infected with 10 deaths. Five died of the strain 017.[92]

10. Pronunciation

The anglicized pronunciation /klɒsˈtrɪdiəm dɪˈfɪsɪliː/ is common, though a restored pronunciation /dɪˈfɪkɪleɪ/ is also used. The classical Latin pronunciation is reconstructed as [klōsˈtrɪdiũ dɪfˈfɪkɪlɛ]. Difficile commonly is mispronounced /diːfiˈsiːl/, as though it were French. The word is from the Greek kloster (κλωστήρ), "spindle",[93] and Latin difficile, "difficult, obstinate".[94]

11. Research

- Efforts to generate a vaccine are ongoing as of 2015, with promising initial results.[95][96]

- CDA-1 and CDB-1 (also known as MDX-066/MDX-1388 and MBL-CDA1/MBL-CDB1) is an investigational, monoclonal antibody combination co-developed by Medarex and Massachusetts Biologic Laboratories (MBL) to target and neutralize C. difficile toxins A and B, for the treatment of CDI. Merck & Co., Inc. gained worldwide rights to develop and commercialize CDA-1 and CDB-1 through an exclusive license agreement signed in April 2009. It is intended as an add-on therapy to one of the existing antibiotics to treat CDI.[97][98][99]

- Nitazoxanide is a synthetic nitrothiazolyl-salicylamide derivative indicated as an antiprotozoal agent (FDA-approved for the treatment of infectious diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia) and also is currently being studied in C. difficile infections vs. vancomycin.[100]

- Rifaximin,[100] is a clinical-stage semisynthetic, rifamycin-based, nonsystemic antibiotic for CDI. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of infectious diarrhea and is being developed by Salix Pharmaceuticals.

- Other drugs for the treatment of CDI are under development and include rifalazil,[100] tigecycline,[100] ramoplanin,[100] ridinilazole, and SQ641.[101]

- Research has studied whether the vermiform appendix has any importance in, C. difficile. The appendix is thought to have a function of housing good gut flora. In a study conducted in 2011, it was shown that when C. difficile bacteria were introduced into the gut, the appendix housed cells that increased the antibody response of the body. The B cells of the appendix migrate, mature, and increase the production of toxin A-specific IgA and IgG antibodies, leading to an increased probability of good gut flora surviving against the C. difficile bacteria.[102]

- Taking non-toxic types of C. difficile after an infection has promising results with respect to preventing future infections.[103]

- Bezlotoxumab, a human monoclonal antibody, was approved for the treatment of C. difficile by the FDA in 2016. It is given by injection. The medication hopefully will become available in the first quarter of 2017.[104]

- A study in 2017 linked severe disease to trehalose in the diet.[105]

12. Other Animals

- Colitis-X (in horses)

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Medicine:Clostridium_difficile_infection

References

- "Inpatient diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile infection". Clinical Medicine 12 (6): 583–588. 2012. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.12-6-583. https://dx.doi.org/10.7861%2Fclinmedicine.12-6-583

- Bomers, Marije (April 2015). "Rapid, Accurate, and On-Site Detection of C. difficile in Stool Samples". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 110 (4): 588–594. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.90. PMID 25823766. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fajg.2015.90

- "Clinical prediction rules to optimize cytotoxin testing for Clostridium difficile in hospitalized patients with diarrhea". The American Journal of Medicine 100 (5): 487–95. May 1996. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(95)00016-X. PMID 8644759. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0002-9343%2895%2900016-X

- "Clostridium difficile: A Cause of Diarrhea in Children". JAMA Pediatrics 167 (6): 592. June 2013. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2551. PMID 23733223. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160130103201/http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1695335.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 322–4. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- Di Bella, Stefano; Ascenzi, Paolo; Siarakas, Steven; Petrosillo, Nicola; di Masi, Alessandra (2016-01-01). "Clostridium difficile Toxins A and B: Insights into Pathogenic Properties and Extraintestinal Effects". Toxins 8 (5): 134. doi:10.3390/toxins8050134. ISSN 2072-6651. PMID 27153087. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4885049

- "The low molecular mass GTP-binding protein Rh is affected by toxin a from Clostridium difficile". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 95 (3): 1026–31. 1995. doi:10.1172/JCI117747. PMID 7883950. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=441436

- "Binary Bacterial Toxins: Biochemistry, Biology, and Applications of Common Clostridium and Bacillus Proteins". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews : MMBR 68 (3): 373–402, table of contents. 2004. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.3.373-402.2004. PMID 15353562. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=515256

- "A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality". The New England Journal of Medicine 353 (23): 2442–9. December 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051639. PMID 16322602. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMoa051639

- McDonald LC (August 2005). "Clostridium difficile: responding to a new threat from an old enemy". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 26 (8): 672–5. doi:10.1086/502600. PMID 16156321. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110604191632/http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/infDis/Cdiff_ICHE08_05.pdf.

- "Clostridium difficile infection: New developments in epidemiology and pathogenesis". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 7 (7): 526–36. July 2009. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2164. PMID 19528959. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnrmicro2164

- Luciano, JA; Zuckerbraun, BS (December 2014). "Clostridium difficile infection: prevention, treatment, and surgical management". The Surgical clinics of North America 94 (6): 1335–49. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2014.08.006. PMID 25440127. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.suc.2014.08.006

- "Scientists probe whether C. difficile is linked to eating meat". CBC News. 2006-10-04. Archived from the original on 24 October 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20061024034645/http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2006/10/04/cdifficile-meat.html.

- Dumyati, Ghinwa; Stone, Nimalie D.; Nace, David A.; Crnich, Christopher J.; Jump, Robin L. P. (2017). "Challenges and Strategies for Prevention of Multidrug-Resistant Organism Transmission in Nursing Homes". Current Infectious Disease Reports 19 (4). doi:10.1007/s11908-017-0576-7. ISSN 1523-3847. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11908-017-0576-7

- "Clostridium difficile Infection Information for Patients | HAI | CDC" (in en-us). Archived from the original on 30 March 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170330023956/https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/Cdiff-patient.html. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- "Acquisition of Clostridium difficile by hospitalized patients: evidence for colonized new admissions as a source of infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 166 (3): 561–7. September 1992. doi:10.1093/infdis/166.3.561. PMID 1323621. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Finfdis%2F166.3.561

- Halsey J (2008). "Current and future treatment modalities for Clostridium difficile-associated disease". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 65 (8): 705–15. doi:10.2146/ajhp070077. PMID 18387898. https://dx.doi.org/10.2146%2Fajhp070077

- "Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection". Archives of Internal Medicine 170 (9): 784–90. May 2010. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.89. PMID 20458086. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Farchinternmed.2010.89

- "Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10 (3): 225–33. March 2012. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.030. PMID 22019794. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cgh.2011.09.030

- "Tube feeding, the microbiota, and Clostridium difficile infection". World J. Gastroenterol. 16 (2): 139–42. January 2010. PMID 20066732. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2806551

- Sarah A. Kuehne; Stephen T. Cartman; John T. Heap; Michelle L. Kelly; Alan Cockayne; Nigel P. Minton (2010). "The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection". Nature 467 (7316): 711–3. doi:10.1038/nature09397. PMID 20844489. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature09397

- "Surgical Pathology Criteria: Pseudomembranous Colitis". Archived from the original on 3 September 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140903205050/http://surgpathcriteria.stanford.edu/gi/pseudomembranous-colitis/differentialdiagnosis.html.

- Manual of Clinical Microbiology (8th ed.). Washington DC: ASM Press. 2003. ISBN 1-55581-255-4.

- "Repeat Stool Testing to Diagnose Clostridium difficile Infection Using Enzyme Immunoassay Does Not Increase Diagnostic Yield". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 9 (8): 665–669.e1. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.04.030. PMID 21635969. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cgh.2011.04.030

- Anna Salleh (2009-03-02). "Researchers knock down gastro bug myths". ABC Science Online. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090303090746/http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/03/02/2504466.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- "Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile". Nature 458 (7242): 1176–9. 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07822. PMID 19252482. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2679968

- "Clostridium difficile toxin and faecal lactoferrin assays in adult patients". Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur 2 (15): 1827–30. 2000. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01343-5. PMID 11165926. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1286-4579%2800%2901343-5

- Chen, S; Gu, H; Sun, C; Wang, H; Wang, J (June 2017). "Rapid detection of Clostridium difficile toxins and laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infections.". Infection 45 (3): 255–262. doi:10.1007/s15010-016-0940-9. PMID 27601055. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs15010-016-0940-9

- JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Oct. 2010, p. 3738–3741

- "FAQs (frequently asked questions) "Clostridium Difficile"". Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161207162256/http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/cdiff/Cdiff_tagged.pdf.

- "Clostridium difficile Infection Information for Patients | HAI | CDC". Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161216143416/https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/cdiff/cdiff-patient.html. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Origin of Adverse Drug Events in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #158. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. July 2013. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160407104449/http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb158.jsp. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- Curbing Antibiotics Tied to Britain's Drop in C. diff. Jan 2017 http://www.medpagetoday.com/gastroenterology/generalgastroenterology/62719

- "Fighting fire with fire: is it time to use probiotics to manage pathogenic bacterial diseases?". Current Gastroenterology Reports 14 (4): 343–8. August 2012. doi:10.1007/s11894-012-0274-4. PMID 22763792. http://www.springerlink.com/content/l6616838648v1907/.

- "Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis.". Annals of Internal Medicine 157 (12): 878–88. 18 December 2012. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00563. PMID 23362517. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326%2F0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00563

- "Probiotics in Clostridium difficile Infection". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 45 (Suppl): S154–8. November 2011. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822ec787. PMID 21992956. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5322762

- McFarland LV (April 2006). "Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic associated diarrhea and the treatment of Clostridium difficile disease". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 101 (4): 812–22. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00465.x. PMID 16635227. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1572-0241.2006.00465.x

- "Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 5: CD006095. 31 May 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub3. PMID 23728658. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD006095.pub3

- Mayo Clinic C. diff prevention http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/c-difficile/DS00736/DSECTION=prevention

- "Strategies to Prevent Clostridium difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update.". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 35 (6): 628–45. Jun 2014. doi:10.1086/676023. PMID 24799639. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F676023

- Roehr B (21 September 2007). "Alcohol Rub, Antiseptic Wipes Inferior at Removing Clostridium difficile". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20131030025331/http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/563232.

- Banach, David B.; Bearman, Gonzalo; Barnden, Marsha; Hanrahan, Jennifer A.; Leekha, Surbhi; Morgan, Daniel J.; Murthy, Rekha; Munoz-Price, L. Silvia et al. (11 January 2018). "Duration of Contact Precautions for Acute-Care Settings". Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 39: 1–18. doi:10.1017/ice.2017.245. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2Fice.2017.245

- "Host S-nitrosylation inhibits clostridial small molecule–activated glucosylating toxins". Nature Medicine 17 (9): 1136–41. 2011. doi:10.1038/nm.2405. PMID 21857653. Lay summary – ScienceDaily (21 August 2011). http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3277400

- Laidman J (29 December 2011). "Flush With Germs: Lidless Toilets Spread C. difficile". Medscape. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160420144825/http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/756189.

- "Cleaning agents 'make bug strong'". BBC News Online. 2006-04-03. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20061108192447/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/4871840.stm. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- Boyce et al. 2008

- Manian et al. 2010

- "Performance Feedback, Ultraviolet Cleaning Device, and Dedicated Housekeeping Team Significantly Improve Room Cleaning, Reduce Potential for Spread of Common, Dangerous Infection". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2014-01-15. https://innovations.ahrq.gov/profiles/performance-feedback-ultraviolet-cleaning-device-and-dedicated-housekeeping-team. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- Nelson, RL; Suda, KJ; Evans, CT (3 March 2017). "Antibiotic treatment for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea in adults.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD004610. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004610.pub5. PMID 28257555. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD004610.pub5

- "Comparative effectiveness of Clostridium difficile treatments: a systematic review". Annals of Internal Medicine 155 (12): 839–47. 20 December 2011. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00007. PMID 22184691. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326%2F0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00007

- McDonald, LC; Gerding, DN; Johnson, S; Bakken, JS; Carroll, KC; Coffin, SE; Dubberke, ER; Garey, KW et al. (19 March 2018). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA).". Clinical Infectious Diseases 66 (7): 987–994. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy149. PMID 29562266. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fcid%2Fciy149

- Surawicz, Christina M; Brandt, Lawrence J; Binion, David G; Ananthakrishnan, Ashwin N; Curry, Scott R; Gilligan, Peter H; McFarland, Lynne V; Mellow, Mark et al. (26 February 2013). "Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infections". The American Journal of Gastroenterology 108 (4): 478–498. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.4. PMID 23439232. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fajg.2013.4

- "Fidaxomicin: a novel macrocyclic antibiotic for the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection.". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 69 (11): 933–43. 1 June 2012. doi:10.2146/ajhp110371. PMID 22610025. https://dx.doi.org/10.2146%2Fajhp110371

- Cornely OA (December 2012). "Current and emerging management options for Clostridium difficile infection: what is the role of fidaxomicin?". Clinical Microbiology and Infection 18 Suppl 6: 28–35. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12012. PMID 23121552. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2F1469-0691.12012

- Cunha, Burke A. (2013). Antibiotic Essentials 2013 (12 ed.). p. 133. ISBN 978-1-284-03678-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=3sL3RlLMKtEC&pg=PT133.

- Koo, HL; Koo, DC; Musher, DM; DuPont, HL (1 March 2009). "Antimotility agents for the treatment of Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis.". Clinical Infectious Diseases 48 (5): 598–605. doi:10.1086/596711. PMID 19191646. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F596711

- Stroehlein JR (2004). "Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infection". Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology 7 (3): 235–9. doi:10.1007/s11938-004-0044-y. PMID 15149585. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11938-004-0044-y

- "Clostridium difficile: controversies and approaches to management". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 22 (6): 517–24. December 2009. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833229ce. PMID 19738464. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FQCO.0b013e32833229ce

- Pillai A, Nelson R (23 January 2008). Pillai, Anjana. ed. "Probiotics for treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated colitis in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004611. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004611.pub2. PMID 18254055. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F14651858.CD004611.pub2

- "Fecal Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection in Older Adults: A Review.". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 61 (8): 1394–8. August 2013. doi:10.1111/jgs.12378. PMID 23869970. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fjgs.12378

- Drekonja, D; Reich, J; Gezahegn, S; Greer, N; Shaukat, A; MacDonald, R; Rutks, I; Wilt, TJ (5 May 2015). "Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine 162 (9): 630–8. doi:10.7326/m14-2693. PMID 25938992. https://dx.doi.org/10.7326%2Fm14-2693

- "Duodenal Infusion of Donor Feces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile". The New England Journal of Medicine 368 (5): 407–15. January 2013. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. PMID 23323867. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMoa1205037

- Jop De Vrieze (30 August 2011). "The Promise of Poop". Science 341: 954–957. doi:10.1126/science.341.6149.954. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.341.6149.954

- Keller, JJ; Kuijper, EJ (2015). "Treatment of recurrent and severe Clostridium difficile infection". Annual Review of Medicine 66: 373–86. doi:10.1146/annurev-med-070813-114317. PMID 25587656. https://dx.doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev-med-070813-114317

- Smith, Peter Andrey (10 November 2015). "Fecal Transplants Made (Somewhat) More Palatable". The New York Times: p. D5. Archived from the original on 13 November 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20151113030546/http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/10/health/fecal-transplants-made-somewhat-more-palatable.html?ref=health. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- "Systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes following emergency surgery for Clostridium difficile colitis". The British Journal of Surgery 99 (11): 1501–13. November 2012. doi:10.1002/bjs.8868. PMID 22972525. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fbjs.8868

- "Emergency colectomy for fulminant Clostridium difficile colitis: Striking the right balance". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 46 (10): 1222–7. October 2011. doi:10.3109/00365521.2011.605469. PMID 21843039. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109%2F00365521.2011.605469

- "Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever". The New England Journal of Medicine 359 (18): 1932–40. October 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0707500. PMID 18971494. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMra0707500

- others], editor-in-chief, Frank J. Domino ; associate editors, Robert A. Baldor (2014). The 5-minute clinical consult 2014 (22nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-4511-8850-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=2C2MAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA258.

- Lessa, Fernanda C.; Mu, Yi; Bamberg, Wendy M.; Beldavs, Zintars G.; Dumyati, Ghinwa K.; Dunn, John R.; Farley, Monica M.; Holzbauer, Stacy M. et al. (26 February 2015). "Burden of Infection in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine 372 (9): 825–834. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1408913. PMID 25714160. https://dx.doi.org/10.1056%2FNEJMoa1408913

- "Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141117113220/http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf#page=51. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "Hospital Acquired Infections Are a Serious Risk - Consumer Reports". Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161210183700/http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/health/hospital-acquired-infections/index.htm.

- "Intestinal flora in newborn infants with a description of a new pathogenic anaerobe, Bacillus difficilis". American Journal of Diseases of Children 49 (2): 390–402. 1935. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1935.01970020105010. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120405152215/http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/summary/49/2/390.

- "Clostridium difficile and the aetiology of pseudomembranous colitis". Lancet 311 (8073): 1063–6. May 1978. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90912-1. PMID 77366. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0140-6736%2878%2990912-1

- "Trust confirms 49 superbug deaths". BBC News Online. 2006-10-01. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070322074234/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/leicestershire/5396800.stm.

- Hawkes, Nigel (2007-01-11). "Leaked memo reveals that targets to beat MRSA will not be met" (snippet). The Times (London). http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/article1894685.ece. Retrieved 2007-01-11. (Subscription content?)

- "C. difficile blamed for 9 death in hospital near Montreal". Canoe.ca. 27 October 2006. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. https://archive.is/20120708084747/http://cnews.canoe.ca/CNEWS/Canada/2006/10/27/2145519.html. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- "12th person dies of C. difficile at Quebec hospital". CBC News. 18 November 2006. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20071021130323/http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2006/11/18/difficile-outbreak.html.

- Hospitals struck by new killer bug An article by Manchester free newspaper 'Metro', 7 May 2008 http://www.metro.co.uk/news/article.html?in_article_id=146311&in_page_id=34

- "C. difficile outbreak linked to fatal strain" . CTV News. 28 February 2007. http://toronto.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20070228/cdifficile_mississauga_outbreak_070228/20070228/

- "Superbug in hospitals linked to four deaths". Irish Independent. 10 October 2007. http://www.independent.ie/national-news/superbug-in-hospitals-linked-to-four-deaths-1139062.html.

- "Welcome to the Public Inquiry into the Outbreak of Clostridium difficile in Northern Trust Hospitals" http://www.cdiffinquiry.org/index.htm

- Healthcare watchdog finds significant failings in infection control at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust, United Kingdom: Healthcare Commission, 11 October 2007, archived from the original on 21 December 2007, https://web.archive.org/web/20071221000642/http://www.healthcarecommission.org.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases.cfm?cit_id=5875&FAArea1=customWidgets.content_view_1&usecache=false

- Smith, Rebecca; Rayner, Gordon; Adams, Stephen (11 October 2007). "Health Secretary intervenes in superbug row". Daily Telegraph (London). Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080420232805/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/main.jhtml?xml=%2Fnews%2F2007%2F10%2F11%2Fncdiff611.xml.

- Ärhäkkä suolistobakteeri on tappanut jo kymmenen potilasta – HS.fi – Kotimaa http://www.hs.fi/kotimaa/artikkeli/%C3%84rh%C3%A4kk%C3%A4+suolistobakteeri+on+tappanut+jo+kymmenen+potilasta/1135232592793

- "Possible C Diff link to Drogheda deaths". RTÉ News. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121023214832/http://www.rte.ie/news/2009/1110/health.html.

- 199 hit by the killer diarrhea at Herlev Hospital , BT 3 March 2010 http://www.bt.dk/sygdomme/199-ramt-af-draeber-diarre-paa-herlev-sygehus

- (Herlev, Amager, Gentofte and Hvidovre)

- Four hospitals affected by the dangerous bacterium , TV2 News 7 May 2010 http://nyhederne.tv2.dk/article/30384149/

- "Deadly superbug reaches NZ". 3 News NZ. 30 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140415074534/http://www.3news.co.nz/Deadly-superbug-reaches-NZ/tabid/423/articleID/274618/Default.aspx.

- "C. difficile linked to 26th death in Ontario". CBC News. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110724230856/http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/story/2011/07/24/tor-c-difficile-death-stcatharines623.html. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "10 punkter för att förhindra smittspridning i Region Skåne" (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 5 March 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150305042943/http://www.skane.se/sv/Webbplatser/Lasarettet_i_Ystad/Om_Lasarettet_i_Ystad/Nyheter/Nyheter/10-punkter-for-att-forhindra-smittspridning-i-Region-Skane/.

- Liddell-Scott. "κλωστήρ". Greek-English Lexicon (Oxford){{inconsistent citations}}

- Cawley, Kevin. "Difficilis". Latin Dictionary and Grammar Aid (University of Notre Dame). http://www.archives.nd.edu/cgi-bin/lookup.pl?stem=Difficilis&ending=. Retrieved 2013-03-16{{inconsistent citations}}

- Lessa, FC; Gould, CV; McDonald, LC (August 2012). "Current status of Clostridium difficile infection epidemiology". Clinical Infectious Diseases 55 Suppl 2: S65-70. doi:10.1093/cid/cis319. PMID 22752867. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3388017

- Ghose, C; Kelly, CP (March 2015). "The prospect for vaccines to prevent Clostridium difficile infection.". Infectious disease clinics of North America 29 (1): 145–62. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2014.11.013. PMID 25677708. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.idc.2014.11.013

- Campus, University of Massachusetts Worcester. "op-line data from randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled Phase 2 clinical trial indicate statistically significant reduction in recurrences of CDAD". Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20101227152634/http://umassmed.edu/Content.aspx?id=62670. Retrieved 2011-08-16

- CenterWatch. "Clostridium Difficile-Associated Diarrhea". Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110929154200/http://www.centerwatch.com/clinical-trials/results/new-therapies/nmt-details.aspx?CatID=554. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- Business, Highbeam. "MDX 066, MDX 1388 Medarex, University of Massachusetts Medical School clinical data (phase II)(diarrhea)". Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121014202844/http://business.highbeam.com/436989/article-1G1-193894218/mdx-066-mdx-1388-medarex-university-massachusetts-medical. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

- "Clostridium difficile infection: update on emerging antibiotic treatment options and antibiotic resistance". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy 8 (5): 555–64. May 2010. doi:10.1586/eri.10.28. PMID 20455684. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3138198

- Moore, John H.; van Opstal, Edward; Kolling, Glynis L.; Shin, Jae Hyun; Bogatcheva, Elena; Nikonenko, Boris; Einck, Leo; Phipps, Andrew J. et al. (2016-05-01). "Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection using SQ641, a capuramycin analogue, increases post-treatment survival and improves clinical measures of disease in a murine model". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 71 (5): 1300–1306. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv479. ISSN 1460-2091. PMID 26832756. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4830414

- Barlow, Andrew; Muhleman, Mitchel; Gielecki, Jerzy; Matusz, Petru; Tubbs, R. Shane; Loukas, Marios (2013). "The Vermiform Appendix: A Review". Clinical Anatomy 26 (7): 833–842. doi:10.1002/ca.22269. PMID 23716128. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ca.22269.

- Gerding, Dale N.; Meyer, Thomas; Lee, Christine; Cohen, Stuart H.; Murthy, Uma K.; Poirier, Andre; Van Schooneveld, Trevor C.; Pardi, Darrell S. et al. (5 May 2015). "Administration of Spores of Nontoxigenic Strain M3 for Prevention of Recurrent Infection". JAMA 313 (17): 1719. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3725. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.2015.3725

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161103220437/http://www.mercknewsroom.com/news-release/corporate-news/fda-approves-mercks-zinplava-bezlotoxumab-reduce-recurrence-clostridium-. Retrieved 2016-11-01. , FDA Approves Merck’s ZINPLAVA™ (bezlotoxumab) to Reduce Recurrence of Clostridium difficile Infection (CDI) in Adult Patients Receiving Antibacterial Drug Treatment for CDI Who Are at High Risk of CDI Recurrence

- Collins, J (2018). "Dietary trehalose enhances virulence of epidemic Clostridium difficile". Nature 553: 291–294. doi:10.1038/nature25178. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature25178.