Systemic endemic mycoses are a group of dimorphic fungi prevalent in specific geographical locations. Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides spp., Blastomyces dermatitidis, Cryptococcosis gattii, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis are the primary pulmonary fungal pathogens of otherwise healthy people. Acute or chronic fungal infections may manifest as solitary or multiple lung nodules or masses. The most frequent pathogens are histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, and blastomycosis. The nodules have a nonspecific appearance, may be ill or well-defined, have regular or spiculated borders, and may also demonstrate cavitation or ground glass halo.

1. Introduction

Fungi may have a widespread or endemic geographic distribution. Immunocompromised patients are most affected by ubiquitous fungi, such as

Aspergillus,

Candida,

Mucor,

Cryptococcoci neoformans, and

Pneumocystis jiroveci. Immunocompetent individuals or those with chronic conditions may be susceptible to endemic mycoses. Overall, patients with reduced immunity are more vulnerable to complications and disseminated disease from endemic and ubiquitous fungal infections. Additionally, endemic mycoses can be divided into two groups, such as implantation or subcutaneous mycoses in which the pathogen generally infects transcutaneous wounds and systemic mycoses in which the respiratory tract is the primary route of transmission into the human host, i.e., aerogenic and dust inhalation (construction, farming, landscaping, excavation) [

1,

2]. Systemic endemic mycoses are a group of dimorphic fungi prevalent in specific geographical locations.

Histoplasma capsulatum,

Coccidioides spp.,

Blastomyces dermatitidis,

Cryptococcosis gattii, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis are the primary pulmonary fungal pathogens of otherwise healthy people.

Histoplasma capsulatum is found worldwide, but particularly in North, Central, and South America. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis or valley fever is caused by the dimorphic fungi

C. immitis and

C. posadasii. It is endemic in the southwestern parts of the USA (California, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Nevada) and parts of Central and South America (Brazil, Argentina, Mexico). Blastomycosis is mainly reported in North America and Africa. Cryptococcosis (

C. gattii) is endemic in the Pacific Northwest, Central and South America, Asia, and India. Paracoccidioidomycosis (

P. brasiliensis) is endemic in Latin America, particularly Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and Argentina [

3,

4,

5]. Additionally, talaromycosis and emergomycosis are two other important endemic systemic mycoses; however, they are more frequently reported as opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients, particularly in advanced HIV disease. Talaromycosis, caused by

Talaromyces marneffei, is endemic to north-eastern India, southeast Asia, and southern China. Emergomycosis are endemic to Africa (

Emergomyces pasteurianus,

Es africanus), Europe (

Es pasteurianus,

Es europaeus), North America (

Es canadensis), and Asia (

Es pasteurianus,

Es orientalis) [

6,

7].

The majority of infected people remain asymptomatic or develop self-limiting respiratory symptoms (up to 6 weeks). The clinical presentation of these granulomatous diseases can vary from asymptomatic to disseminated infection and depends on the amount of environmental exposure, virulent strain, host’s immune status, and extremes of age. Symptoms are often subacute but may have an acute presentation. Cough, fever, chills, anorexia, weight loss, fatigue, headache, and chest pain are all possible clinical symptoms. Patients may also manifest dermatological symptoms, such as erythema nodosum or multiforme, and rheumatological manifestations. The severe disease form may spread hematogenously to bones, skin, joints, and central nervous system [

1,

4].

The diagnosis of systemic endemic mycosis is challenging and frequently misinterpreted for other diseases (e.g., bacterial or viral pneumonia, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, lung cancer, metastases). Both clinicians and radiologists may be unfamiliar with the disease manifestations, especially those from non-endemic areas. Familiarization with these diseases by health professionals is of crucial importance as they are becoming increasingly relevant worldwide due to traveling and immigration [

4,

8].

2. Imaging Findings

2.1. Lung Nodule or Mass

Acute or chronic fungal infections may manifest as solitary or multiple lung nodules or masses. The most frequent pathogens are histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis,

cryptococcosis, and blastomycosis [

4]. The nodules have a nonspecific appearance, may be ill or well-defined, have regular or spiculated borders, and may also demonstrate cavitation or ground glass halo

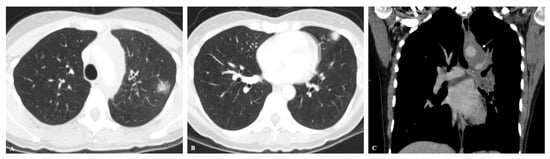

(Figure 1). Additionally, a presenting dominant nodule or mass may be associated with other satellite nodules or bronchovascular beading [

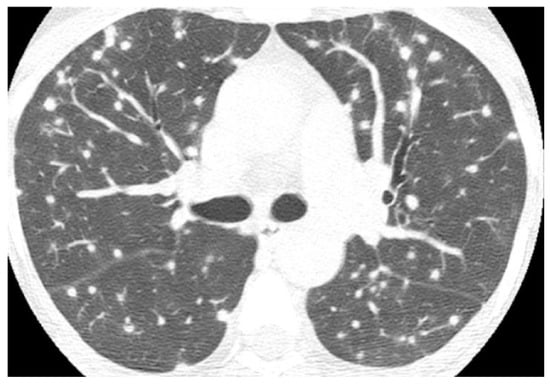

9]. Three-in-bud opacities are less common but may be seen in cases of bronchiolitis. More severe infections may present with multiple solid or cavitary nodules with a tendency toward confluence (

Figure 2) [

4,

10]. In histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, and coccidioidomycosis, the size of the nodules frequently ranges from less than 10 to 30 mm and they have a lower lobe predominance. The nodules in histoplasmosis and cryptococcosis are also predominantly peripherally located (

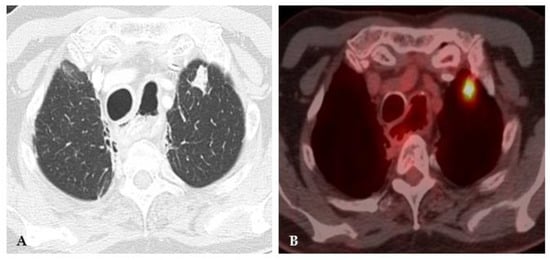

Figure 3) [

4,

5,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Lung masses are the second most common finding in blastomycosis (after lobar and segmental consolidation), and they may measure up to 10 cm in diameter [

4,

14]. Pulmonary granulomata resulting from histoplasmosis may continue to enlarge over time (average of 1.7 mm per year) due to proliferation of fibrosis at the periphery of the nodule, secondary to an abnormal host response [

9].

Figure 1. (A,B) Axial CT images showing peripherally located solid nodules with ground-glass halo in the upper left lobe, in a patient with acute histoplasmosis infection. (C) Coronal CT image depicts left mediastinal and hilar enlarged lymph nodes (arrow).

Figure 2. Axial CT image in a patient with histoplasmosis shows numerous bilateral and randomly distributed solid nodules, some of them with peripheral ground-glass halos.

Figure 3. Cryptococcosis in a 63-year-old man with clinical history of colon cancer, heavy smoking and cough for 3 months. (A) Axial and sagittal (B) images show an irregular solid mass in the right upper lobe adjacent to the pleura and ground-glass halo.

Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies are typically visualized in histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis, which may be bulky, especially in the latter [

4]. In acute infection, Fluorine 18 (18F)–fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT shows avid uptake in both the pulmonary infection and lymph nodes but with a greater degree of pulmonary uptake. During the subacute phase of infection, the pulmonary nodules or masses demonstrate a decrease in FDG activity more quickly than the adenopathy (

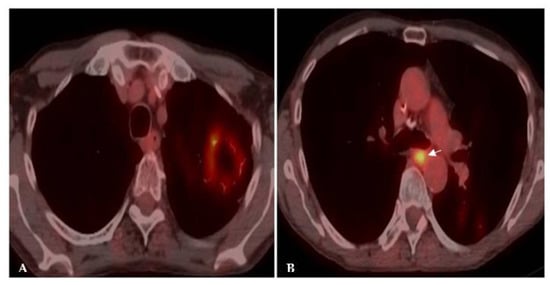

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). This is the opposite of lung cancer in which the malignancy usually retains higher FDG avidity. This finding, also known as the flip-flop fungus sign, discloses the benign granulomatous disease nature, particularly associated with histoplasmosis [

15]. As the infection heals, the infected mediastinal lymph nodes and pulmonary granulomata can calcify, showing central (target) or diffuse calcification, a typical finding in histoplasmosis [

4,

8,

9]. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pulmonary calcified nodules are not typical findings in coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis and blastomycosis [

12,

13,

14].

Figure 4. Acute histoplasmosis infection. (A) Axial CT image depicts a left upper lobe nodule. (B) FDG PET/CT shows avid uptake in the pulmonary infection.

Figure 5. Chronic histoplasmosis infection. FDG PET/CT images show higher FDG activity in a mediastinal draining lymph node (arrow) in (B) than in the left upper lobe cavitary mass (A). The flip-flop fungus sign discloses the benign granulomatous nature of the disease.

Although nodules or masses can predominate on imaging findings, mixed patterns and additional findings are frequently visualized: consolidations, ground-glass opacities, bronchovascular and septal thickening, and airway disease. Pleural effusions are not a common finding but may be present. More rarely, other pulmonary complications, such as pneumothorax, bronchopleural fistula, and lung abscess, can be found [

4,

5,

8,

11].

The main concern in differential diagnosis is the exclusion of malignancy (primary lung cancer and metastases). Other differentials include tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacteria, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and further infectious fungi, such as semi-invasive or invasive aspergillosis, mucormycosis, and candidiasis, especially in immunocompromised patients [

4,

8,

11,

16].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof8111132