The Kübler-Ross model, or the Five Stages of Grief, postulates a series of emotions experienced by terminally ill patients prior to death, or people who have lost a loved one, wherein the five stages are: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Although commonly referenced in popular media, the existence of these stages has not been empirically demonstrated and the model is not considered helpful in explaining the grieving process. It is considered to be of historical value but outdated in scientific terms and in clinical practice. The model was first introduced by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in her 1969 book On Death and Dying, and was inspired by her work with terminally ill patients. Motivated by the lack of instruction in medical schools on the subject of death and dying, Kübler-Ross examined death and those faced with it at the University of Chicago's medical school. Kübler-Ross's project evolved into a series of seminars which, along with patient interviews and previous research, became the foundation for her book. Although Kübler-Ross is commonly credited with creating stage models, earlier bereavement theorists and clinicians such as Erich Lindemann, Collin Murray Parkes, and John Bowlby used similar models of stages of phases as early as the 1940s. Later in her life, Kübler-Ross noted that the stages are not a linear and predictable progression and that she regretted writing them in a way that was misunderstood. "Kübler-Ross originally saw these stages as reflecting how people cope with illness and dying," observed grief researcher Kenneth J. Doka, "not as reflections of how people grieve."

- model

- terminally ill

- historical value

1. Stages of Grief

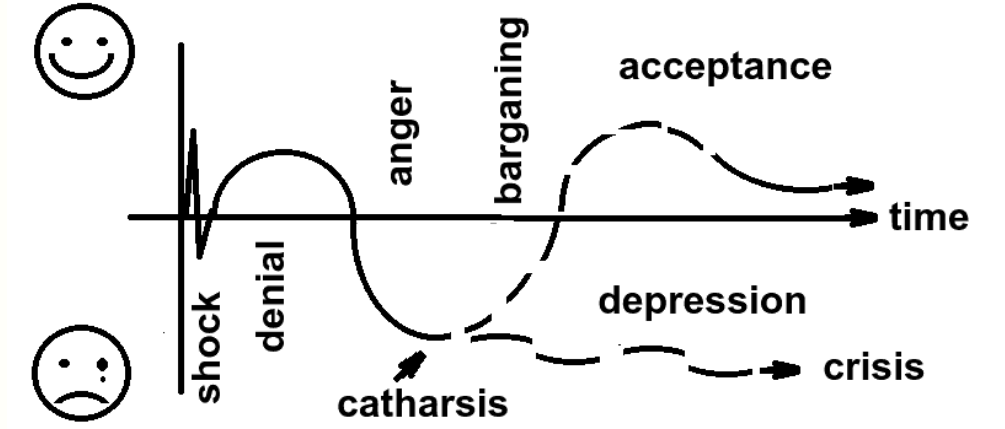

Kübler-Ross originally developed stages to describe the process patients with terminal illness go through as they come to terms with their own deaths; it was later applied to grieving friends and family as well, who seemed to undergo a similar process.[1] The stages, popularly known by the acronym DABDA, include:[2]

- Denial – The first reaction is denial. In this stage, individuals believe the diagnosis is somehow mistaken, and cling to a false, preferable reality.

- Anger – When the individual recognizes that denial cannot continue, they become frustrated, especially at proximate individuals. Certain psychological responses of a person undergoing this phase would be: "Why me? It's not fair!"; "How can this happen to me?"; "Who is to blame?"; "Why would this happen?".

- Bargaining – The third stage involves the hope that the individual can avoid a cause of grief. Usually, the negotiation for an extended life is made in exchange for a reformed lifestyle. People facing less serious trauma can bargain or seek compromise. Examples include the terminally ill person who "negotiates with God" to attend a daughter's wedding, an attempt to bargain for more time to live in exchange for a reformed lifestyle or a phrase such as "If I could trade their life for mine".

- Depression – "I'm so sad, why bother with anything?"; "I'm going to die soon, so what's the point?"; "I miss my loved one; why go on?"

During the fourth stage, the individual despairs at the recognition of their mortality. In this state, the individual may become silent, refuse visitors and spend much of the time mournful and sullen. - Acceptance – "It's going to be okay."; "I can't fight it; I may as well prepare for it."

In this last stage, individuals embrace mortality or inevitable future, or that of a loved one, or other tragic event. People dying may precede the survivors in this state, which typically comes with a calm, retrospective view for the individual, and a stable condition of emotions.

In a book co-authored with David Kessler and published posthumously, Kübler-Ross expanded her model to include any form of personal loss, such as the death of a loved one, the loss of a job or income, major rejection, the end of a relationship or divorce, drug addiction, incarceration, the onset of a disease or an infertility diagnosis, and even minor losses, such as a loss of insurance coverage.[3] Kessler has also proposed "Meaning" as a sixth stage of grief.[4]

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Kessler applied the five stages to our responses to the virus, saying: “It’s not a map but it provides some scaffolding for this unknown world.”

“There's denial, which we saw a lot of early on: This virus won't affect us. There's anger: You're making me stay home and taking away my activities. There's bargaining: Okay, if I social distance for two weeks everything will be better, right? There's sadness: I don't know when this will end. And finally there's acceptance. This is happening; I have to figure out how to proceed. Acceptance, as you might imagine, is where the power lies. We find control in acceptance. I can wash my hands. I can keep a safe distance. I can learn how to work virtually."[5]

2. Criticism

Criticisms of this five-stage model of grief center mainly on a lack of empirical research and empirical evidence supporting the stages as described by Kübler-Ross and, to the contrary, empirical support for other modes of the expression of grief. Moreover, Kübler-Ross' model is the product of a particular culture at a particular time and might not be applicable to people of other cultures. These points have been made by many experts,[6] including Professor Robert J. Kastenbaum (1932–2013) who was a recognized expert in gerontology, aging, and death. In his writings, Kastenbaum raised the following points:[7][8]

- The existence of these stages as such has not been demonstrated.

- No evidence has been presented that people actually do move from Stage 1 through Stage 5.

- The limitations of the method have not been acknowledged.

- The line is blurred between description and prescription.

- The resources, pressures, and characteristics of the immediate environment, which can make a tremendous difference, are not taken into account.

A widely cited 2003 study of bereaved individuals conducted by Maciejewski and colleagues at Yale University obtained some findings consistent with a five-stage hypothesis but others inconsistent with it. Several letters were also published in the same journal criticizing this research and arguing against the stage idea.[9] It was pointed out, for example, that instead of "acceptance" being the final stage of grieving, the data actually showed it was the most frequently endorsed item at the first and every other time point measured;[10] that cultural and geographical bias within the sample population was not controlled for;[11] and that out of the total number of participants originally recruited for the study, nearly 40% were excluded from the analysis who did not fit the stage model.[12] In subsequent work, Prigerson & Maciejewski focused on acceptance (emotional and cognitive) and backed away from stages, writing that their earlier results "might more accurately be described as 'states' of grief."[13]

George Bonanno, Professor of Clinical Psychology at Columbia University, in his book The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After a Loss,[14] summarizes peer-reviewed research based on thousands of subjects over two decades and concludes that a natural psychological resilience is a principal component of grief[15] and that there are no stages of grief to pass. Bonanno's work has also demonstrated that absence of grief or trauma symptoms is a healthy outcome.[16][17]

Among social scientists, another criticism is a lack of theoretical underpinning.[6] [18] Because the stages arose from anecdotes and not underlying theoretical principles it contains conceptual confusion. For example, some stages represent emotions while other represent cognitive processes. Also, there is no rationale for arbitrary dividing lines between states. On the other hand, there are other theoretically based, scientific perspectives that better represent the course of grief and bereavement such as: trajectories approach, cognitive stress theory, meaning making approach, psychosocial transition model, two-track model, dual process model, and the task model.[19]

Misapplication can be harmful if it leads bereaved persons to feel that they are not coping appropriately or it can result in ineffective support by members of their social network and/or health care professionals.[6][12] The stages were originally meant to be descriptive but over time became prescriptive. Some caregivers dealt with clients who were distressed that they did not experience the stages in "the right order" or failed to experience one or more of the stages of grief.

Criticism and lack of support in peer-reviewed research or objective clinical observation by many practitioners in the field has led to the labels of myth and fallacy in the notion that there are stages of grief.[17][18][20][21] Nevertheless, the model's use has persisted in popular news and entertainment media.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Philosophy:K%C3%BCbler-Ross_model

References

- Feldman, David B (7 July 2017). "Why the Five Stages of Grief Are Wrong". https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/supersurvivors/201707/why-the-five-stages-grief-are-wrong.

- A Topical Approach to Life-Span Development. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2007. ISBN 978-0-07-338264-7.

- Kübler-Ross, Elisabeth; Kessler, David (2014). On grief & grieving : finding the meaning of grief through the five stages of loss. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9781476775555. OCLC 863077888. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/863077888

- Kessler, David (5 November 2019). Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief. ISBN 9781501192739. https://books.google.com/books?id=H920DwAAQBAJ.

- Berinato, Scott. "That Discomfort You’re Feeling Is Grief". https://hbr.org/2020/03/that-discomfort-youre-feeling-is-grief.

- "Cautioning Health-Care Professionals". Omega 74 (4): 455–473. March 2017. doi:10.1177/0030222817691870. PMID 28355991. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5375020

- Kastenbaum, Robert (1998). Death, Society, and Human Experience (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Corr, Charles A.; Doka, Kenneth J.; Kastenbaum, Robert (1999). "Dying and Its Interpreters: A Review of Selected Literature and Some Comments on the State of the Field.". OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying 39 (4): 239–259. doi:10.2190/3KGF-52BV-QTNT-UBMX. https://dx.doi.org/10.2190%2F3KGF-52BV-QTNT-UBMX

- "An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief". JAMA 297 (7): 716–23. February 2007. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.716. PMID 17312291. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.297.7.716

- "The stage theory of grief". JAMA 297 (24): 2693; author reply 2693-4. June 2007. doi:10.1001/jama.297.24.2693-a. PMID 17595267. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.297.24.2693-a

- "The stage theory of grief". JAMA 297 (24): 2692–3; author reply 2693-4. June 2007. doi:10.1001/jama.297.24.2692-b. PMID 17595265. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.297.24.2692-b

- "The stage theory of grief". JAMA 297 (24): 2692; author reply 2693-4. June 2007. doi:10.1001/jama.297.24.2692-a. PMID 17595266. https://dx.doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.297.24.2692-a

- "Grief and acceptance as opposite sides of the same coin: setting a research agenda to study peaceful acceptance of loss". The British Journal of Psychiatry 193 (6): 435–7. December 2008. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053157. PMID 19043142. https://dx.doi.org/10.1192%2Fbjp.bp.108.053157

- Bonanno, George (2009). The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us about Life After Loss. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01360-9. https://archive.org/details/othersideofsadne00bona.

- "Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events?". The American Psychologist 59 (1): 20–8. January 2004. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. PMID 14736317. http://rcin.org.pl/Content/60213.

- "The neuroscience of true grit". Scientific American 304 (3): 28–33. March 2011. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0311-28. PMID 21438486. Bibcode: 2011SciAm.304c..28S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fscientificamerican0311-28

- Konigsberg, Ruth Davis (January 29, 2011). "New Ways to Think About Grief". http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2042372-2,00.html.

- "The 'five stages' in coping with dying and bereavement: strengths, weaknesses and some alternatives". Mortality 24 (4): 405–417. 23 October 2018. doi:10.1080/13576275.2018.1527826. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F13576275.2018.1527826

- "Models of coping with bereavement: A review". Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press. 2001. pp. 375–403. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-18149-000.

- Shermer, Michael (1 November 2008). "Five Fallacies of Grief: Debunking Psychological Stages". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/five-fallacies-of-grief/.

- "The myths of coping with loss". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57 (3): 349–57. June 1989. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.57.3.349. PMID 2661609. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0022-006x.57.3.349