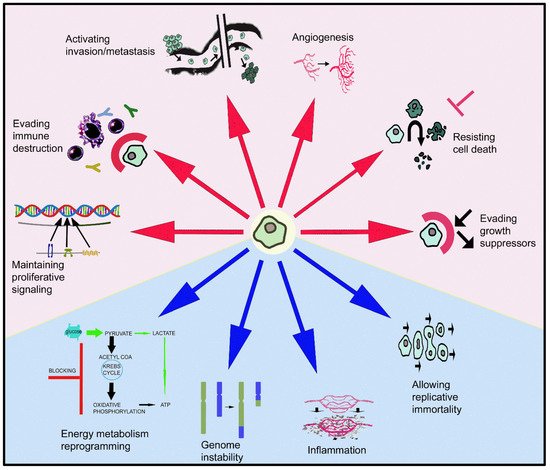

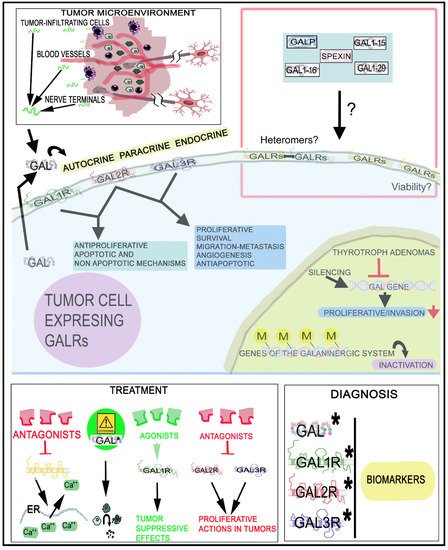

Peptidergic systems play an important role in cancer progression. The galaninergic system (the peptide galanin and its receptors: galanin 1, 2 and 3) is involved in tumorigenesis, the invasion and migration of tumor cells and angiogenesis and it has been correlated with tumor stage/subtypes, metastasis and recurrence rate in many types of cancer. Galanin exerts a dual action in tumor cells: a proliferative or an antiproliferative effect depending on the galanin receptor involved in these mechanisms. Galanin receptors could be used in certain tumors as therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers for treatment, prognosis and surgical outcome.

- galanin

- galanin receptor

- galanin receptor antagonist

- galanin receptor agonist

1. Introduction

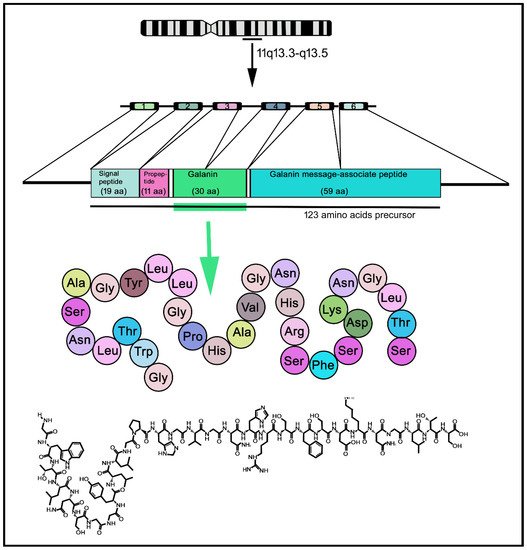

2. The Galaninergic System: Galanin and Its Receptors

3. The Galaninergic System and Cancer

3.1. Galanin and Neuroendocrine Tumors

| Cancer | Actions/Presence | References |

|---|---|---|

| Corticotroph adenoma Human |

- High GAL expression (RIA) | [102] |

| - GAL in 84% of tumors (IH) | [103] | |

| - GAL expression: smaller adenomas and better prognosis (IH) | [105] | |

| - GAL release and responded to corticotropin-releasing factor | [135] | |

| Ganglioneuroma Human |

- No correlation between prognosis/tumor markers and GAL level (RIA) | [136] |

| - GAL1R/GAL3R immunoreactivity decrease (IH) | [137] | |

| Insulinoma Rat Rin14B cell line |

- GAL1R expression (Northern blot, in situ hybridization) | [32] |

| Insulinoma Rat RINm5F cell line |

- GAL moderately suppressed insulin accumulation, but did not affect cell proliferation | [138] |

| - Pancreatic beta-cells: GAL inhibited adenylate cyclase activity and insulin secretion | [53] | |

| Insulinoma Mouse |

- Beta TC-1 cells: GAL, released from sympathetic nerve terminals, inhibited pro-insulin gene expression stimulated by glucagon-like peptide-I (Northern blot) | [139] |

| Neuroblastic tumors Human |

- GAL mRNA, GAL immunoreactivity and GAL binding sites expression (IH, in situ hybridization) | [137] |

| - Low level of GAL binding sites correlated with survival; GAL/GALR expression related to tumor differentiation stage (RIA, IH, in situ hybridization) | [136,137] | |

| Neuroblastoma Human |

- No correlation between prognosis/tumor markers and GAL concentration | [136] |

| - GAL expression; GAL2R mRNA was less common than GAL1R mRNA (IH, in situ hybridization) | [104] | |

| - GAL1R/GAL3R highly expressed; GAL promoted tumor growth (IH, in situ hybridization) | [137] | |

| Neuroblastoma Human IMR32 cell line |

- Dense core secretory vesicles: coexistence of GAL and beta-amyloid (IH) | [140] |

| Neuroblastoma Human SH-SY5Y cell line |

- GAL2R mediated apoptosis. GAL antiproliferative potency: 100-fold higher in SY5Y/GAL2R cells than in SY5Y/GAL1R cells | [12] |

| - GAL2R transfection: cell proliferation was blocked and caspase-dependent apoptotic mechanisms induced | [12] | |

| Neuroblastoma Rat B104 cell line |

- GAL, GAL2R and GAL3R mRNAs were detected, but not GAL1R mRNA (reverse transcription-PCR) | [141] |

| - GAL promoted cell proliferation | ||

| Paraganglioma Human |

- GAL expression (IH) | [108,112,142] |

| Paraganglioma Human carotid body |

- GAL was detected in 18% of tumors (IH) | [108] |

| Paraganglioma Human jugulo tympanic |

- GAL was detected in 40% of tumors (IH) | [108] |

| Phaeochromocytoma Human |

- High GAL2R mRNA expression (Western blot) | [143] |

| - Higher GAL concentration than in normal adrenal glands (RIA) | [144] | |

| Phaeochromocytoma Rat PC12 cell line |

- GAL inhibited cell proliferation and GAL1R, GAL2R and GAL3R mRNA expression, but not GAL mRNA (reverse transcription-PCR) | [141] |

| Pituitary adenoma Human |

- GAL/GALR expression correlated with tumor stage (IH) | [101] |

| Pituitary adenoma Human |

- High GAL3R levels found in some patients who relapsed shortly after surgical intervention (q-PCR) | [145] |

| Pituitary adenoma Rat |

- GAL promoted pituitary cell proliferation and tumor development | [38] |

| Pituitary adenoma Rat MtTW-10 cell line |

- Estradiol increased GAL mRNA level | [146] |

| Prolactinoma Rat |

- GAL concentration increased and GAL promoted tumor development | [147,148] |

| - Levonorgestrel decreased GAL mRNA expression and GAL-expressing cells (IH, in situ hybridization) | [149] | |

| Small-cell lung cancer Human H345, H510 cell lines |

- GAL, via GAL2R, mediated cell proliferation | [88,150] |

| Small-cell lung cancer Human H69, H510 cell lines |

- GAL, via GAL2R, activated G proteins and promoted cell proliferation | [88] |

| - GAL increased the levels of inositol phosphate and intracellular Ca2+ and promoted cell growth | [151] | |

| Small-cell lung cancer Human H345, H510 cell lines |

- Ca2+-mobilizing peptides (e.g., GAL) promoted cell growth. Broad spectrum antagonists directed against multiple Ca2+-mobilizing receptors inhibited cell growth | [150,152] |

| Small-cell lung cancer Human H69, H345, H510 cell lines |

- GAL, via the p42MAPK pathway, promoted cell growth. Protein kinase C inhibitors blocked cell growth induced by GAL | [153,154] |

| Small-cell lung cancer Human SBC-3A cell line, mouse SBC-3A tumor |

- SBC-3A cells secreted the pre-pro-GAL precursor which was extracellular processed to GAL1-20 by plasmin | [155,156] |

| Somatotroph adenoma Human |

- Low GAL level (RIA) | [102] |

| - GAL increased circulating growth hormone level and growth hormone-producing tumors expressed GAL (IH) | [157] | |

| - GAL blocked growth hormone release | [158] | |

| Somatotroph adenoma Rat GH1 cell line |

- GAL inhibited growth hormone release | [159] |

| Somatotroph adenoma Mouse |

- GAL mRNA level and peptide concentration increased | [147] |

| - GAL secretion increased | [160] | |

| Thyrotroph adenoma Rat |

- GAL gene expression blocked | [147] |

| Thyrotroph adenoma Mouse |

- GAL synthesis inhibited | [160] |

3.2. Galanin and Gastric Cancer

| Actions/Presence | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer | ||

| Human | - Fibers containing GAL: increased in longitudinal muscle layer, lamina muscularis mucosae and neoplastic proliferation vicinity (IH) | [175] |

| - Myenteric plexus: neurons showed a high expression of caspases 3/8 and low GAL expression (IH) | [175] | |

| - GAL/GAL1R level reduced | [176] | |

| - GAL2R/GAL3R level unchanged (RT-PCR) | [176] | |

| - Lower level of GAL in pre-operative samples (and plasma) when compared with that found in post-operative samples or in healthy donors. Gastric cancer tissues: GAL/GAL1R level was lower compared with that found in adjacent regions GAL2R/GAL3R: no change (Western blot; RT-PCR; ELISA) | [176] | |

| - GAL low level: used as biomarker. GAL protein/mRNA level related to tumor size, tumor node metastasis stage and lymph node metastasis | [176] | |

| Human Gastric cancer cell lines |

- GAL expression decreased: restored with a demethylating agent. GAL hypermethylation: impaired GAL tumor suppressor action. GAL downregulation: due to epigenetic inactivation (Q-MSP, Western blot) | [177] |

| - GAL: decreased cell proliferation | [178] | |

| Rats | - GAL blocked gastric carcinogenesis by inhibiting antral epithelial cell proliferation | [13] |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | ||

| Human | - GAL/GAL1R silencing: apoptosis in drug-sensitive/resistant cell lines and enhanced the effects mediated by chemotherapy. GAL mRNA: overexpressed. High GAL level: related to poor disease-free survival of early-stage CRC patients (IH, ELISA, RT-PCR, Western blot) | [7,106,117,121] |

| - Enteric nervous system: number of neurons containing GAL increased in regions located close to the tumor (IH) (IH, RT-PCR, ELISA) | [8] | |

| - CRC patients: more GAL-immunoreactive neurons in comparison to healthy samples (IH, ELISA) | [121] | |

| - GAL in the vicinity of cancer cell invasion (IH, ELISA) | [121] | |

| - Blood samples: increased GAL concentration. High GAL level: cancer cells. Lowest GAL level: muscular layer placed distant from tumors. GAL: CRC tumor biomarker (ELISA, IH) | [179] | |

| - GAL mRNA level: related to adenocarcinoma size/stage. Correlation between higher GAL expression and shorter disease-free survival (RT-PCR) | [106,117] | |

| - CRC cells showed a high GAL expression: more malignant and involved in tumor recurrence. High GAL expression: spread of cancer stem cells (metastasis) (RT-PCR) | [180] | |

| - High GAL expression: associated with poor prognosis (stage II) and tumor recurrence. GAL expression: related to CRC aggressive behavior (RT-PCR) | [180] | |

| Human (tissue and cell lines) | - CRC cells/tissues: higher GAL levels than non-tumor cells/tissues | [106,117,179,180] |

| - CRC tissue: increased GAL gene/protein expression. CRC cell lines: GAL/GAL1R silencing promoted apoptosis. GAL1R silencing promoted FLIPL down-regulation (IH, ELISA, RT-PCR) | [106,117,121] | |

| Human HCT116 cell line |

- Cells overexpressing GAL2R were more chemosensitive to bevacizumab than control cells | [181] |

| Rat | - GAL decreased the incidence of colon tumors | [182] |

3.3. Galanin and Colorectal Cancer

3.4. Galanin and Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma

| Actions/Presence | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Human | - High GAL level (RT-PCR) | [120] |

| - GAL1R gene promoter: frequently methylated (Q-MSP) | [191] | |

| - Methylation status of some peptide-encoding genes, including GAL, is related with survival and recurrence. Methylation changes: possible molecular marker for HNSCC risk/prognosis (Q-MSP) | [192] | |

| - GAL/GALR epigenetic variants: markers for prognosis prediction (Q-MSP) | [193,194] | |

| - Poor survival: associated with methylation of GAL/GAL1R genes. Hypermethylation: inactivation of GAL/GAL1R/GAL2R genes (Q-MSP) | [195] | |

| Human Cell lines |

- Apoptosis: mediated by GAL2R but not by GAL1R. GAL1R/GAL2R: tumor suppressors in a p53-independent manner | [11] |

| - GAL2R transfection into HNSCC cells: cell proliferation inhibited. GAL2R re-expression: blocked cell proliferation (showing mutant p53) | [113,196,197] | |

| - GAL1R/GAL2R negative HNSCC cells: GAL1R re-expression suppressed tumor cell proliferation via ERK1/2-mediated actions on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and cyclin D1 | [113,197] | |

| - GAL/GAL1R blocked HNSCC and oral tumor cell proliferation by cell-cycle arrest (RT-PCR, ELISA, Q-MSP) | [123,177,196,198] | |

| - GAL1R blocked tumor cell proliferation through the activation of ERK1/2 | [196] | |

| - GAL2R promoted an antitumor effect by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptotic mechanisms (caspase 3-dependent) | [197] | |

| - GAL2R suppressed HNSCC cell viability. HEp-2 cells: GAL2R mediated apoptotic mechanisms (caspase-independent) by downregulating ERK1/2 and inducing Bim | [199] | |

| Human Cell lines, tumor samples |

- GAL2R overexpression: favored survival/proliferation by activating PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK-dependent pathways. Ras-related protein 1 (Rap1): involved in HNSCC progression. | [122] |

| - GAL/GAL1R: tumor suppressor. GAL1R absent in some cell lines (Q-MSP, RT-PCR) | [177,178,198] | |

| - GAL1R promoter: widely hypermethylated and related to reduced GAL1R expression. GAL1R/GAL2R hypermethylation: associated with higher recurrence rate and reduced disease-free survival (RT-PCR, Q-MSP) | [191,194,198,200] | |

| - GAL1R methylation status: potential biomarker for predicting clinical outcomes. Methylation: related to carcinogenesis and decreased GAL1R expression (RT-PCR, Q-MSP) | [193,194,198] | |

| Human (cell lines) Mouse |

- GAL (released from nerves) activated GAL2R expressed in tumor cells inducing NFATC2-mediated transcription of cyclooxygenase-2 and GAL. GAL released from tumor cells promoted neuritogenesis, favoring perineural invasion | [84] |

| Mouse | - GAL2R promoted tumor angiogenesis through the p38-MAPK-mediated inhibition of tristetraprolin (TTP), leading to an enhanced secretion of cytokines. GAL2R activated Ras-related protein 1b (Rap1B) favoring a p38-mediated inactivation of TTP, which acted as a destabilize cytokine transcript | [201] |

3.5. Galanin and Glioma

| Actions/Presence | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Human | - GAL/GAL3R expression: no correlation with oligodendroglial, astrocytic and mixed neural–glial tumors | [30] |

| - High-grade glioma (WHO grade IV): related to GAL3R expression | [30] | |

| - Endothelial/immune cells: GAL3R expression. Around blood vessels: GAL1R/GAL2R not observed (IH) | [30] | |

| - GAL1R, followed by GAL3R; GAL2R absent (astrocytic/oligodendroglia tumors) (IH, autoradiography, reverse transcription-PCR) | [30,118] | |

| - Glioma-associated macrophages: GAL3R expression (quantitative PCR) | [59,204] | |

| - No correlation between proliferative activity and GAL/GAL binding levels (IH, autoradiography, reverse transcription-PCR) | [118] | |

| - Cerebrospinal fluid (glioblastoma): reduced GAL level | [203] | |

| Human Mice |

- GAL blocked, via GAL1R, the proliferation of glioma cells and tumor growth. These effects were mediated through ERK1/2 signal activation. No cytotoxic/apoptotic effect was observed | [205] |

3.6. Galanin and Other Cancers

| Actions/Presence | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer Human |

- GAL/pre-pro-GAL mRNA level expression. GALN gene: unlike candidate oncogene (Northern blot) | [101,206] |

| Carcinoma (cardiac, esophageal) Human |

- Fibers containing GAL contacted closely with cancer cells (IH) | [207] |

| Endometrial cancer Human |

- GAL1R DNA methylation indicated malignancy (q-PCR) | [208] |

| Bladder cancer Human |

- GAL1R gene methylation involved in prognosis | [209] |

| Salivary duct carcinoma Human |

- GAL1R/GAL2R: therapeutic targets/prognostic factors. GAL1R/GAL2R methylation rates correlated with overall survival decrease (IH, Q-MSP) | [210] |

| Melanoma Human |

- GAL/GAL1R expression (IH) | [101,119] |

| Pancreas Human |

- GAL promoted SW1990 cell proliferation | [211] |

| Pancreas Rat |

- GAL blocked carcinogenesis and decreased norepinephrine level (IH, HPLC) | [212] |

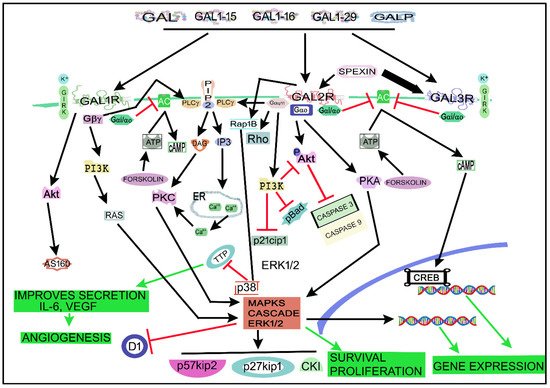

4. The Galaninergic System and Cancer: Signaling Pathways

5. Therapeutic Strategies

6. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers14153755