In most cases, HEAs contain numerous components. Therefore, the equilibrium phase diagrams for such complicated systems must be constructed in 5–6 or more dimensions. Due to this trouble, we are forced to use a simplified approach. Fortunately, the most important features of GB wetting phase transitions [

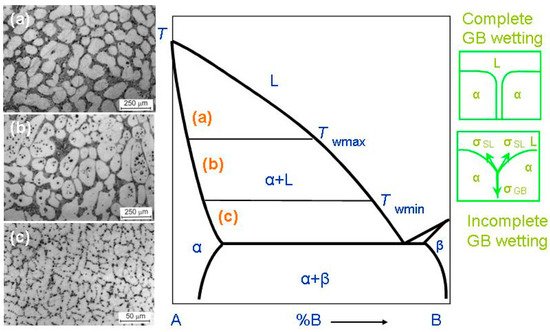

49] can be described using the simple two-dimensional phase diagram for binary alloys like that shown in

Figure 2. Bold lines in this scheme (e.g., solidus, liquidus, solvus, and eutectic lines) depict the bulk phase transitions. The thin lines (like tie-lines at

Twmin and

Twmax) depict the GB phase transformations. When the solidification of HEAs starts, the composition of an alloy can be found in the phase diagram in the liquid area L. Afterwards, by cooling, it crosses the liquidus line and moves into the two-phase area L + α. In this L + α area the melt is in equilibrium with solid solution α. The solid solution α is based on component A. By following cooling, the amount of solid solution α in this L + α mixture increases and the portion of melt L decreases. The composition of remaining melt L follows the liquidus line. Thus, the melt becomes more and more enriched by component B. Similarly, the composition of solidifying phase α changes along the solidus line. If the concentration of component B in α-phase is low, the solidification finishes at the solidus line. Afterwards, the solidified alloy has only phase, namely the solid solution α. However, the portions of α-phase solidified at the end of the process are enriched by the component B. If we discuss the multicomponent HEAs instead of this simple example of binary alloy, the GB wetting transitions would be more complicated. This is because, for example, an HEA with five components is described by the 5D phase diagram. Therefore, when the liquid alloy L with five components starts to crystallize, it can intersect with not only one binary-phase region, α + L, such as in

Figure 2, but numerous multiphase areas. Only afterwards can HEA be completely solid and contain only one α-phase. These multiphase regions can contain more than one liquid phase and one solid phase.

When a polycrystal crosses the α + L area of the phase diagram, it contains, first, the interphase boundaries (IBs) between liquid phase, L, and solid phase, α-phase. It also contains the α/α grain boundaries (GBs). The melt, L, contacts the solid phase, α, in the triple junctions (TJs) between GBs and, respectively, two solid/liquid IBs, (see green schemes on the right-hand side of

Figure 2). The GB has the energy σ

GB and each solid/liquid IB has energy 2σ

SL. If σ

GB < 2σ

SL, (see lower scheme in right-hand side of

Figure 2), the GB has a non-zero contact angle, θ > 0, with the melt. The GB wetting in this case is partial (or incomplete). The micrograph (

c) on the left-hand side of the phase diagram shows an example of how the microstructure of the two-phase α + L polycrystal of the Al–Mg alloy can appear below

Twmin. This sample contains only (Al)/(Al) GBs partially wetted by the Mg-rich melt. If the energy of two solid/liquid IBs, 2σ

SL, is lower than the GB energy, σ

GB > 2σ

SL (see upper scheme in

Figure 2), then the contact angle becomes equal to zero, θ = 0. In this case, the thick melted layer should separate the solid α-grains, and the GB wetting is complete. The transition between complete and partial GB wetting is described for numerous binary alloys. In these alloys the θ value decreases with growing temperature and becomes zero at a certain temperature,

Tw (called the temperature of GB wetting phase transition) [

50,

51,

52]. Above

Tw, the GB is completely wetted. The GB wetting phase-transition is in principle two-dimensional one. Nevertheless, it can be of first or second order, similar to phase transformations in the bulk [

53,

54,

55]. In the case of a first-order GB wetting transition, the first temperature derivative of θ, dθ/d

T, has a discontinuity at

Tw. The dθ/d

T suddenly descends at

Tw from a certain finite value to zero [

50,

53,

54]. In case of the continuous (second-order) wetting transition in GBs, the dθ/d

T value continuously changes with growing

T and smoothly reaches zero dθ/d

T = 0 at

Tw [

54,

55]. One must take into consideration that the σ

GB value can strongly depend both on the grain boundary misorientation angle, χ, and on the grain boundary inclination angle, ψ [

56]. The dependences of GB energy on χ and ψ, σ

GB(χ) and σ

GB (ψ), possess the sharp cusps at certain χ and ψ values [

57]. These special misorientation and inclination angles, χ and ψ, are determined by the coincidence site lattices. Due to this fact, the σ

GB can vary in a rather broad interval of values. Obviously, the lower σ

GB, the higher GB contact with the liquid phase would be at θ. This means that contact angles in a polycrystal can vary in a very broad interval. Moreover, these contact angles for different GBs should decrease with growing temperature with a different rate. Also, the low-angle GBs have lower σ

GB than high-angle GBs, and, therefore, the higher

Tw values [

58]. Actually, the low-angle GBs are not continuous two-dimensional (2D) defects, but consist of arrows of 1D defects, namely dislocations. The GB triple junctions are also 1D defects, and for them, it is lower than for high-angle GBs [

59]. Due to these reasons, the spectrum of

Tw temperatures in a polycrystal can be quite broad.

Such microstructures of two-phase polycrystals can be seen in

Figure 2 (micrographs in the left-hand side). These are the microstructures of the binary Al–Mg alloys. As a result, a conventional phase diagram for 3D-phases gets the additional tie-lines at

Twmin and

Twmax for 2D GB wetting transformations. At

T >

Twmax all GBs in a polycrystal are fully wetted and contain, therefore, the melted layer between solid grains. The micrograph (a) on the left-hand side of the phase diagram shows an example of how the microstructure of the two-phase α + L polycrystal of the Al–Mg alloy can appear above

Twmax. The micrograph (a) is reprinted with permission from ref. [

60]. In this sample, all (Al)/(Al) GBs are completely wetted by the Mg-rich melt. The liquid phase surrounded all solid (Al) grains. The

Twmax tie-line describes the GB wetting transformation for GBs with the lowest σ

GB in a polycrystal. By cooling, the first partially wetted GBs appear below

Twmax. Between

Twmax and

Twmin, the amount of completely wetted GBs decreases with decreasing

T. The micrograph (b) on the left-hand side of the phase diagram shows an example of how the microstructure of the two-phase α + L polycrystal of the Al–Mg alloy can appear between

Twmin and

Twmax. The micrograph (b) is reprinted with permission from ref. [

60]. In this sample, some (Al)/(Al) GBs are completely wetted by the Mg-rich melt and other (Al)/(Al) GBs are partially wetted by the liquid phase. At

Twmin, the completely wetted GBs disappear. The

Twmin tie-line describes the GBs with the highest energy σ

GB. Below

Twmin there are no completely wetted GBs in an alloy, and the polycrystal has only partially wetted GB with θ > 0. The respective example of the Al–Mg alloy is shown in the micrograph (c) on the left-hand side of the phase diagram.