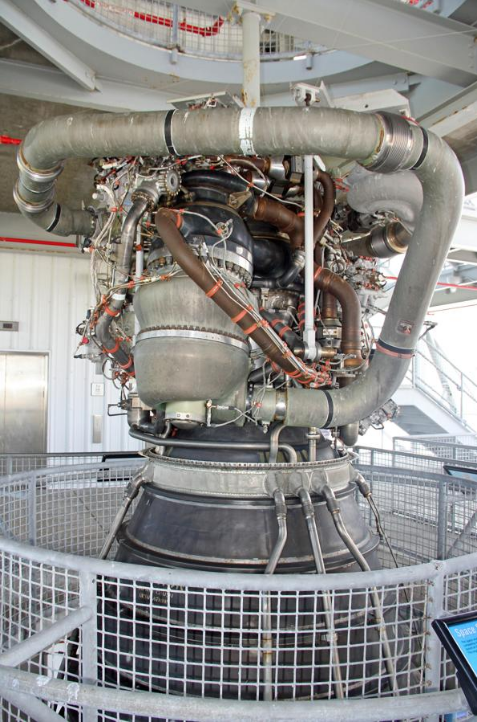

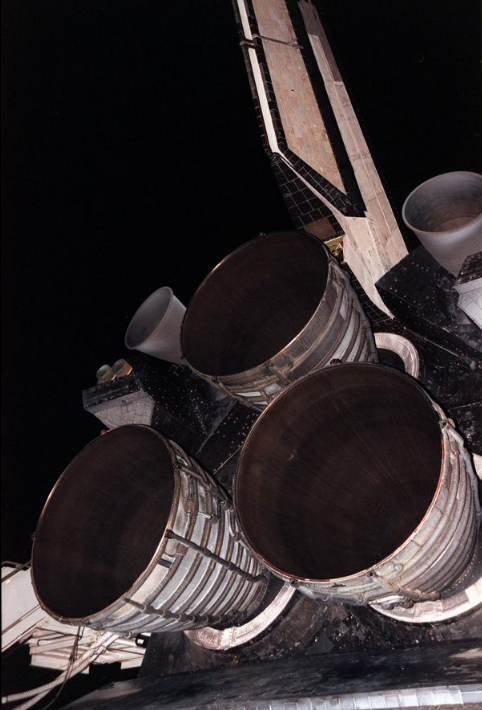

The Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-25, otherwise known as the Space Shuttle main engine (SSME), is a liquid-fuel cryogenic rocket engine that was used on NASA's Space Shuttle and is planned to be used on its successor, the Space Launch System. Designed and manufactured in the United States by Rocketdyne (later known as Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne and Aerojet Rocketdyne), the RS-25 burns cryogenic liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants, with each engine producing 1,859 kN (418,000 lbf) of thrust at liftoff. Although the RS-25 can trace its heritage back to the 1960s, concerted development of the engine began in the 1970s, with the first flight, STS-1, occurring on April 12, 1981. The RS-25 has undergone several upgrades over its operational history to improve the engine's reliability, safety, and maintenance load. Subsequently, the RS-25D is the most efficient liquid fuel rocket engine currently in use. The engine produces a specific impulse (Isp) of 452 seconds (4.43 km/s) in a vacuum, or 366 seconds (3.59 km/s) at sea level, has a mass of approximately 3.5 tonnes (7,700 pounds), and is capable of throttling between 67% and 109% of its rated power level in one-percent increments. The RS-25 operates at temperatures ranging from −253 °C (−423 °F) to 3300 °C (6000 °F). The Space Shuttle used a cluster of three RS-25 engines mounted in the stern structure of the orbiter, with fuel being drawn from the external tank. The engines were used for propulsion during the entirety of the spacecraft's ascent, with additional thrust being provided by two solid rocket boosters and the orbiter's two AJ-10 orbital maneuvering system engines. Following each flight, the RS-25 engines were removed from the orbiter, inspected, and refurbished before being reused on another mission.

- solid rocket

- specific impulse

- liquid hydrogen

1. Components

The RS-25 engine consists of various pumps, valves, and other components which work in concert to produce thrust. Fuel (liquid hydrogen) and oxidizer (liquid oxygen) from the Space Shuttle's external tank entered the orbiter at the umbilical disconnect valves and from there flowed through the orbiter's main propulsion system (MPS) feed lines; whereas in the Space Launch System (SLS), fuel and oxidizer from the rocket's core stage will flow directly into the MPS lines. Once in the MPS lines, the fuel and oxidizer each branch out into separate paths to each engine (three on the Space Shuttle, four on the SLS). In each branch, prevalves then allow the propellants to enter the engine.[1][2]

Once in the engine, the propellants flow through low-pressure fuel and oxidizer turbopumps (LPFTP and LPOTP), and from there into high-pressure turbopumps (HPFTP and HPOTP). From these HPTPs the propellants take different routes through the engine. The oxidizer is split into four separate paths: to the oxidizer heat exchanger, which then splits into the oxidizer tank pressurization and pogo suppression systems; to the low pressure oxidizer turbopump (LPOTP); to the high pressure oxidizer preburner, from which it is split into the HPFTP turbine and HPOTP before being reunited in the hot gas manifold and sent on to the main combustion chamber (MCC); or directly into the main combustion chamber (MCC) injectors.

Meanwhile, fuel flows through the main fuel valve into regenerative cooling systems for the nozzle and MCC, or through the chamber coolant valve. Fuel passing through the MCC cooling system then passes back through the LPFTP turbine before being routed either to the fuel tank pressurization system or to the hot gas manifold cooling system (from where it passes into the MCC). Fuel in the nozzle cooling and chamber coolant valve systems is then sent via pre-burners into the HPFTP turbine and HPOTP before being reunited again in the hot gas manifold, from where it passes into the MCC injectors. Once in the injectors, the propellants are mixed and injected into the main combustion chamber where they are ignited. The burning propellant mixture is then ejected through the throat and bell of the engine's nozzle, the pressure of which creates the thrust.[1]

1.1. Turbopumps

Oxidizer system

The low-pressure oxidizer turbopump (LPOTP) is an axial-flow pump which operates at approximately 5,150 rpm driven by a six-stage turbine powered by high-pressure liquid oxygen from the high-pressure oxidizer turbopump (HPOTP). It boosts the liquid oxygen's pressure from 0.7 to 2.9 MPa (100 to 420 psi), with the flow from the LPOTP then being supplied to the HPOTP. During engine operation, the pressure boost permits the high-pressure oxidizer turbine to operate at high speeds without cavitating. The LPOTP, which measures approximately 450 by 450 mm (18 by 18 in), is connected to the vehicle propellant ducting and supported in a fixed position by being mounted on the launch vehicle's structure.[1]

The HPOTP consists of two single-stage centrifugal pumps (a main pump and a preburner pump) mounted on a common shaft and driven by a two-stage, hot-gas turbine. The main pump boosts the liquid oxygen's pressure from 2.9 to 30 MPa (420 to 4,350 psi) while operating at approximately 28,120 rpm, giving a power output of 23,260 hp (17.34 MW). The HPOTP discharge flow splits into several paths, one of which drives the LPOTP turbine. Another path is to, and through, the main oxidizer valve and enters the main combustion chamber. Another small flow path is tapped off and sent to the oxidizer heat exchanger. The liquid oxygen flows through an anti-flood valve that prevents it from entering the heat exchanger until sufficient heat is present for the heat exchanger to utilize the heat contained in the gases discharged from the HPOTP turbine, converting the liquid oxygen to gas. The gas is sent to a manifold and then routed to pressurize the liquid oxygen tank. Another path enters the HPOTP second-stage preburner pump to boost the liquid oxygen's pressure from 30 to 51 MPa (4,300 psia to 7,400 psia). It passes through the oxidizer preburner oxidizer valve into the oxidizer preburner, and through the fuel preburner oxidizer valve into the fuel preburner. The HPOTP measures approximately 600 by 900 mm (24 by 35 in). It is attached by flanges to the hot-gas manifold.[1]

The HPOTP turbine and HPOTP pumps are mounted on a common shaft. Mixing of the fuel-rich hot gases in the turbine section and the liquid oxygen in the main pump can create a hazard and, to prevent this, the two sections are separated by a cavity that is continuously purged by the engine's helium supply during engine operation. Two seals minimize leakage into the cavity; one seal is located between the turbine section and the cavity, while the other is between the pump section and cavity. Loss of helium pressure in this cavity results in automatic engine shutdown.[1]

Fuel system

The low-pressure fuel turbopump (LPFTP) is an axial-flow pump driven by a two-stage turbine powered by gaseous hydrogen. It boosts the pressure of the liquid hydrogen from 30 to 276 psia (0.2 to 1.9 MPa) and supplies it to the high-pressure fuel turbopump (HPFTP). During engine operation, the pressure boost provided by the LPFTP permits the HPFTP to operate at high speeds without cavitating. The LPFTP operates at around 16,185 rpm, and is approximately 450 by 600 mm (18 by 24 in) in size. It is connected to the vehicle propellant ducting and is supported in a fixed position by being mounted to the launch vehicle's structure.[1]

The HPFTP is a three-stage centrifugal pump driven by a two-stage hot-gas turbine. It boosts the pressure of the liquid hydrogen from 1.9 to 45 MPa (276 to 6,515 psia), and operates at approximately 35,360 rpm with a power of 71,140 hp. The discharge flow from the turbopump is routed to, and through, the main valve and is then split into three flow paths. One path is through the jacket of the main combustion chamber, where the hydrogen is used to cool the chamber walls. It is then routed from the main combustion chamber to the LPFTP, where it is used to drive the LPFTP turbine. A small portion of the flow from the LPFTP is then directed to a common manifold from all three engines to form a single path to the liquid hydrogen tank to maintain pressurization. The remaining hydrogen passes between the inner and outer walls of the hot-gas manifold to cool it and is then discharged into the main combustion chamber. A second hydrogen flow path from the main fuel valve is through the engine nozzle (to cool the nozzle). It then joins the third flow path from the chamber coolant valve. This combined flow is then directed to the fuel and oxidizer preburners. The HPFTP is approximately 550 by 1,100 mm (22 by 43 in) in size and is attached to the hot-gas manifold by flanges.[1]

1.2. Powerhead

Preburners

The oxidizer and fuel preburners are welded to the hot-gas manifold. The fuel and oxidizer enter the preburners and are mixed so that efficient combustion can occur. The augmented spark igniter is a small combination chamber located in the center of the injector of each preburner. The two dual-redundant spark igniters, which are activated by the engine controller, are used during the engine start sequence to initiate combustion in each preburner. They are turned off after approximately three seconds because the combustion process is then self-sustaining. The preburners produce the fuel-rich hot gases that pass through the turbines to generate the power needed to operate the high-pressure turbopumps. The oxidizer preburner's outflow drives a turbine that is connected to the HPOTP and to the oxidizer preburner pump. The fuel preburner's outflow drives a turbine that is connected to the HPFTP.[1]

The speed of the HPOTP and HPFTP turbines depends on the position of the corresponding oxidizer and fuel preburner oxidizer valves. These valves are positioned by the engine controller, which uses them to throttle the flow of liquid oxygen to the preburners and, thus, control engine thrust. The oxidizer and fuel preburner oxidizer valves increase or decrease the liquid oxygen flow, thus increasing or decreasing preburner chamber pressure, HPOTP and HPFTP turbine speed, and liquid oxygen and gaseous hydrogen flow into the main combustion chamber, which increases or decreases engine thrust. The oxidizer and fuel preburner valves operate together to throttle the engine and maintain a constant 6.03:1 propellant mixture ratio.[4]

The main oxidizer and main fuel valves control the flow of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen into the engine and are controlled by each engine controller. When an engine is operating, the main valves are fully open.[1]

Main combustion chamber

Each engine main combustion chamber (MCC) receives fuel-rich hot gas from a hot-gas manifold cooling circuit. The gaseous hydrogen and liquid oxygen enter the chamber at the injector, which mixes the propellants. A small augmented-spark igniter-chamber is located in the center of the injector, and this dual-redundant igniter is used during the engine start sequence to initiate combustion. The igniters are turned off after approximately three seconds because the combustion process is self-sustaining. The main injector and dome assembly are welded to the hot-gas manifold, and the MCC is also bolted to the hot-gas manifold.[1] The MCC comprises a structural shell made of Inconel 718 which is lined with a copper-silver-zirconium alloy called NARloy-Z, developed specifically for the RS-25 in the 1970s. Around 390 channels are machined into the liner wall to carry liquid hydrogen through the liner to provide MCC cooling, as the temperature in the combustion chamber reaches 3300 °C (6000 °F) during flight – higher than the boiling point of iron.[5][6]

1.3. Nozzle

The engine's nozzle is 121 in (3.1 m) long with a diameter of 10.3 in (0.26 m) at its throat and 90.7 in (2.30 m) at its exit.[7] The nozzle is a bell-shaped extension bolted to the main combustion chamber, referred to as a de Laval nozzle. The RS-25 nozzle has an unusually large expansion ratio (about 77.5:1) for the chamber pressure.[8] At sea level, a nozzle of this ratio would normally undergo flow separation of the jet from the nozzle, which would cause control difficulties and could even mechanically damage the vehicle. However, to aid the engine's operation Rocketdyne engineers varied the angle of the nozzle walls from the theoretical optimum for thrust, reducing it near the exit. This raises the pressure just around the rim to an absolute pressure between 4.6 and 5.7 psi (32 and 39 kPa), and prevents flow separation. The inner part of the flow is at much lower pressure, around 2 psi (14 kPa) or less.[9] The inner surface of each nozzle is cooled by liquid hydrogen flowing through brazed stainless steel tube wall coolant passages. On the Space Shuttle, a support ring welded to the forward end of the nozzle is the engine attach point to the orbiter-supplied heat shield. Thermal protection is necessary because of the exposure portions of the nozzles experience during the launch, ascent, on-orbit and entry phases of a mission. The insulation consists of four layers of metallic batting covered with a metallic foil and screening.[1]

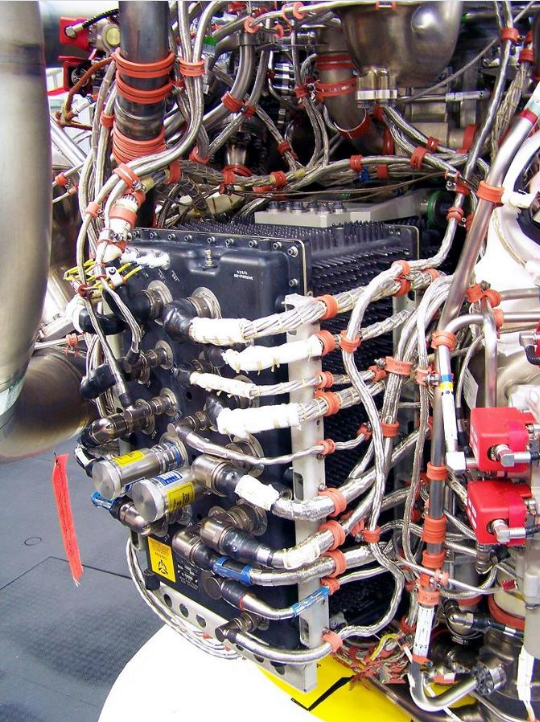

1.4. Controller

Each engine is equipped with a main engine controller (MEC), an integrated computer which controls all of the engine's functions (through the use of valves) and monitors its performance. Built by Honeywell Aerospace, each MEC originally comprised two redundant Honeywell HDC-601 computers,[10] later upgraded to a system composed of two doubly redundant Motorola 68000 (M68000) processors (for a total of four M68000s per controller).[11] Having the controller installed on the engine itself greatly simplifies the wiring between the engine and the launch vehicle, because all the sensors and actuators are connected directly to only the controller, each MEC then being connected to the orbiter's general purpose computers (GPCs) or the SLS's avionics suite via its own engine interface unit (EIU).[12] Using a dedicated system also simplifies the software and thus improves its reliability.

Two independent dual-CPU computers, A and B, form the controller; giving redundancy to the system. The failure of controller system A automatically leads to a switch-over to controller system B without impeding operational capabilities; the subsequent failure of controller system B would provide a graceful shutdown of the engine. Within each system (A and B), the two M68000s operate in "lock-step", thereby enabling each system to detect failures by comparing the signal levels on the buses of the two M68000 processors within that system. If differences are encountered between the two buses, then an interrupt is generated and control turned over to the other system. Because of subtle differences between M68000s from Motorola and the second source manufacturer TRW, each system uses M68000s from the same manufacturer (for instance system A would have two Motorola CPUs while system B would have two CPUs manufactured by TRW). Memory for block I controllers was of the plated-wire type, which functions in a manner similar to magnetic core memory and retains data even after power is turned off.[13] Block II controllers used conventional CMOS static RAM.[11]

The controllers were designed to be tough enough to survive the forces of launch, and proved to be extremely resilient to damage. During the investigation of the Challenger accident the two MECs (from engines 2020 and 2021), recovered from the seafloor, were delivered to Honeywell Aerospace for examination and analysis. One controller was broken open on one side, and both were severely corroded and damaged by marine life. Both units were disassembled and the memory units flushed with deionized water. After they were dried and vacuum baked, data from these units was retrieved for forensic examination.[14]

Main valves

To control the engine's output, the MEC operates five hydraulically actuated propellant valves on each engine; the oxidizer preburner oxidizer, fuel preburner oxidizer, main oxidizer, main fuel, and chamber coolant valves. In an emergency, the valves can be fully closed by using the engine's helium supply system as a backup actuation system.[1]

In the Space Shuttle the main oxidizer and fuel bleed valves were used after shutdown to dump any residual propellant, with residual liquid oxygen venting through the engine and residual liquid hydrogen venting through the liquid hydrogen fill and drain valves. After the dump was completed, the valves closed and remained closed for the remainder of the mission.[1]

A coolant control valve is mounted on the combustion chamber coolant bypass duct of each engine. The engine controller regulates the amount of gaseous hydrogen allowed to bypass the nozzle coolant loop, thus controlling its temperature. The chamber coolant valve is 100% open before engine start. During engine operation, it is 100% open for throttle settings of 100 to 109% for maximum cooling. For throttle settings between 65 and 100%, its position ranged from 66.4 to 100% open for reduced cooling.[1]

1.5. Gimbal

Each engine is installed with a gimbal bearing, a universal ball and socket joint which is bolted to the launch vehicle by its upper flange and to the engine by its lower flange. It represents the thrust interface between the engine and the launch vehicle, supporting 7,480 lb (3,390 kg) of engine weight and withstanding over 500,000 lb (230,000 kg) of thrust. As well as providing a means to attach the engine to the launch vehicle, the gimbal bearing allows the engine to be pivoted (or "gimballed") around two axes of freedom with a range of ±10.5°.[15] This motion allows the engine's thrust vector to be altered, thus steering the vehicle into the correct orientation. The bearing assembly is approximately 290 by 360 mm (11 by 14 in), has a mass of 105 lb (48 kg), and is made of titanium alloy.[3]

The low-pressure oxygen and low-pressure fuel turbopumps were mounted 180° apart on the orbiter's aft fuselage thrust structure. The lines from the low-pressure turbopumps to the high-pressure turbopumps contain flexible bellows that enable the low-pressure turbopumps to remain stationary while the rest of the engine is gimbaled for thrust vector control, and also to prevent damage to the pumps when loads were applied to them. The liquid-hydrogen line from the LPFTP to the HPFTP is insulated to prevent the formation of liquid air.[1]

1.6. Helium System

In addition to fuel and oxidizer systems, the launch vehicle's main propulsion system is also equipped with a helium system consisting of ten storage tanks in addition to various regulators, check valves, distribution lines, and control valves. The system is used in-flight to purge the engine and provides pressure for actuating engine valves within the propellant management system and during emergency shutdowns. During entry, on the Space Shuttle, any remaining helium was used to purge the engines during reentry and for repressurization.[1]

2. History

2.1. Development

The history of the RS-25 traces back to the 1960s when NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and Rocketdyne were conducting a series of studies on high-pressure engines, developed from the successful J-2 engine used on the S-II and S-IVB upper stages of the Saturn V rocket during the Apollo program. The studies were conducted under a program to upgrade the Saturn V engines, which produced a design for a 350,000 lbf upper-stage engine known as the HG-3.[16] As funding levels for Apollo wound down the HG-3 was cancelled as well as the upgraded F-1 engines already being tested.[17] It was the design for the HG-3 that would form the basis for the RS-25.[18]

Meanwhile, in 1967, the US Air Force funded a study into advanced rocket propulsion systems for use during Project Isinglass, with Rocketdyne asked to investigate aerospike engines and Pratt & Whitney (P&W) to research more efficient conventional de Laval nozzle-type engines. At the conclusion of the study, P&W put forward a proposal for a 250,000 lbf engine called the XLR-129, which used a two-position expanding nozzle to provide increased efficiency over a wide range of altitudes.[19][20]

In January 1969 NASA awarded contracts to General Dynamics, Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, and North American Rockwell to initiate early development of the Space Shuttle.[21] As part of these 'Phase A' studies, the involved companies selected an upgraded version of the XLR-129, developing 415,000 lbf, as the baseline engine for their designs.[19] This design can be found on many of the planned Shuttle versions right up to the final decision. However since NASA was interested in pushing the state of the art in every way they decided to select a much more advanced design in order to "force an advancement of rocket engine technology".[8][19] They called for a new design based on a high-pressure combustion chamber running around 3000 psi, which increases the performance of the engine.

Development began in 1970, when NASA released a request for proposal for 'Phase B' main engine concept studies, requiring development of a throttleable, staged combustion, de Laval-type engine.[8][19] The request was based on the then-current design of the Space Shuttle which featured two reusable stages, the orbiter and a manned fly-back booster, and required one engine which would be able to power both vehicles via two different nozzles (12 booster engines with 550,000 lbf sea level thrust each and 3 orbiter engines with 632,000 lbf vacuum thrust each).[8] Rocketdyne, P&W and Aerojet General were selected to receive funding although, given P&W's already-advanced development (demonstrating a working 350,000 lbf concept engine during the year) and Aerojet General's prior experience in developing the 1,500,000 lbf M-1 engine, Rocketdyne was forced to put a large amount of private money into the design process to allow the company to catch up to its competitors.[19]

By the time the contract was awarded, budgetary pressures meant that the shuttle's design had changed to its final orbiter, external tank and two boosters configuration, and so the engine was only required to power the orbiter during ascent.[8] During the year-long 'Phase B' study period, Rocketdyne was able to make use of their experience developing the HG-3 engine to design their SSME proposal, producing a prototype by January 1971. The engine made use of a new Rocketdyne-developed copper-zirconium alloy (called NARloy-Z), and was tested on February 12, 1971, producing a chamber pressure of 3172 psi. The three participating companies submitted their engine development bids in April 1971, with Rocketdyne being awarded the contract on July 13, 1971—although work did not begin on engine development until March 31, 1972, due to a legal challenge from P&W.[8][19]

Following the awarding of the contract, a preliminary design review was carried out in September 1972, followed by a critical design review in September 1976 after which the engine's design was set and construction of the first set of flight-capable engines began. Final review of all the Space Shuttle's components, including the engines, was conducted in 1979. The design reviews operated in parallel with several test milestones, initial tests consisting of individual engine components which identified shortcomings with various areas of the design, including the HPFTP, HPOTP, valves, nozzle and fuel preburners. The individual engine component tests were followed by the first test of a complete engine (0002) on March 16, 1977. NASA specified that, prior to the Shuttle's first flight, the engines must have undergone at least 65,000 seconds of testing, a milestone that was reached on March 23, 1980, with the engine having undergone 110,253 seconds of testing by the time of STS-1 both on test stands at Stennis Space Center and installed on the Main Propulsion Test Article (MPTA). The first set of engines (2005, 2006 and 2007) were delivered to Kennedy Space Center in 1979 and installed on Columbia, before being removed in 1980 for further testing and reinstalled on the orbiter. The engines, which were of the first manned orbital flight (FMOF) configuration and certified for operation at 100% rated power level (RPL), were operated in a twenty-second flight readiness firing on February 20, 1981, and, after inspection, declared ready for flight.[8]

2.2. Space Shuttle Program

Each Space Shuttle had three RS-25 engines, installed in the aft structure of the Space Shuttle orbiter in the Orbiter Processing Facility prior to the orbiter being transferred to the Vehicle Assembly Building. If necessary the engines could be changed on the pad. The engines, drawing propellant from the Space Shuttle external tank (ET) via the orbiter's main propulsion system (MPS), were ignited at T−6.6 seconds prior to liftoff (with each ignition staggered by 120 ms[22]), which allowed their performance to be checked prior to ignition of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), which committed the shuttle to the launch.[23] At launch, the engines would be operating at 100% RPL, throttling up to 104.5% immediately following liftoff. The engines would maintain this power level until around T+40 seconds, where they would be throttled back to around 70% to reduce aerodynamic loads on the shuttle stack as it passed through the region of maximum dynamic pressure, or max Q.[19][22][24] The engines would then be throttled back up until around T+8 minutes, at which point they would be gradually throttled back down to 67% to prevent the stack exceeding 3 g of acceleration as it became progressively lighter due to propellant consumption. The engines were then shut down, a procedure known as main engine cutoff (MECO), at around T+8.5 minutes.[19]

After each flight the engines would be removed from the orbiter and transferred to the Space Shuttle Main Engine Processing Facility (SSMEPF), where they would be inspected and refurbished in preparation for reuse on a subsequent flight.[25] A total of 46 reusable RS-25 engines, each costing around US$40 million, were flown during the Space Shuttle program, with each new or overhauled engine entering the flight inventory requiring flight qualification on one of the test stands at Stennis Space Center prior to flight.[22][26][27]

Upgrades

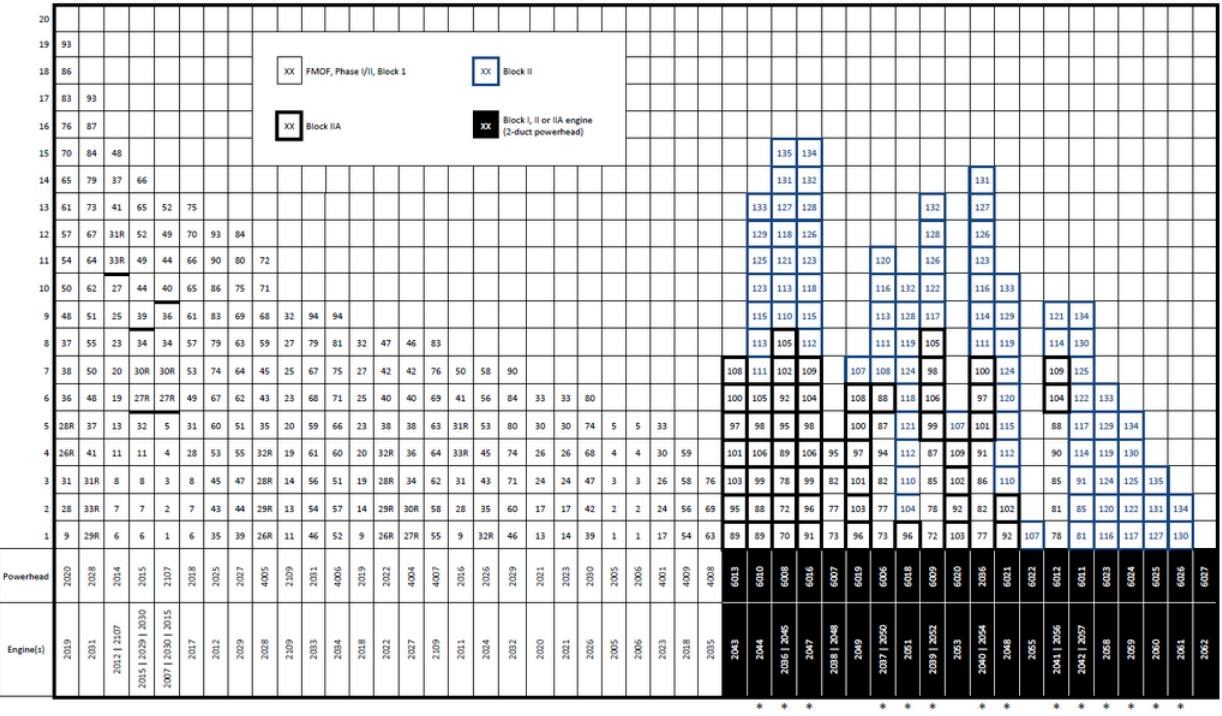

Over the course of the Space Shuttle program, the RS-25 went through a series of upgrades, including combustion chamber changes, improved welds and turbopump changes in an effort to improve the engine's performance and reliability and so reduce the amount of maintenance required after use. As a result, several versions of the RS-25 were used during the program:[6][19][21][22][28][29][30][31][32]

- FMOF (first manned orbital flight) – Certified for 100% rated power level (RPL). Used for the orbital flight test missions STS-1—STS-5 (engines 2005, 2006 and 2007).

- Phase I – Used for missions STS-6—STS-51-L, the Phase I engine offered increased service life and was certified for 104% RPL.

- Phase II (RS-25A) – First flown on STS-26, the Phase II engine offered a number of safety upgrades and was certified for 104% RPL & 109% full power level (FPL) in the event of a contingency.

- Block I (RS-25B) – First flown on STS-70, the Block I engines offered improved turbopumps featuring ceramic bearings, half as many rotating parts and a new casting process reducing the number of welds. Block I improvements also included a new, two-duct powerhead (rather than the original design, which featured three ducts connected to the HPFTP and two to the HPOTP), which helped improve hot gas flow, and an improved engine heat exchanger.

- Block IA (RS-25B) – First flown on STS-73, the Block IA engine offered main injector improvements.

- Block IIA (RS-25C) – First flown on STS-89, the Block IIA engine was an interim model used whilst certain components of the Block II engine completed development. Changes included a new large throat main combustion chamber (which had originally been recommended by Rocketdyne in 1980), improved low pressure turbopumps and certification for 104.5% RPL to compensate for a 2 seconds (0.020 km/s) reduction in specific impulse (original plans called for the engine to be certified to 106% for heavy International Space Station payloads, but this was not required and would have reduced engine service life). A slightly modified version first flew on STS-96.

- Block II (RS-25D) – First flown on STS-104, the Block II upgrade included all of the Block IIA improvements plus a new high pressure fuel turbopump. This model was ground-tested to 111% FPL in the event of a contingency abort, and certified for 109% FPL for use during an intact abort.

Engine throttle/output

The most obvious effects of the upgrades the RS-25 received through the Space Shuttle program were the improvements in engine throttle. Whilst the FMOF engine had a maximum output of 100% RPL, Block II engines could throttle as high as 109% or 111% in an emergency, with usual flight performance being 104.5%. These increases in throttle level made a significant difference to the thrust produced by the engine:[3][22]

| Sea level | Vacuum | |

|---|---|---|

| 100% thrust | 1,670 kN (380,000 lbf) | 2,090 kN (470,000 lbf) |

| 104.5% thrust | 1,750 kN (390,000 lbf) | 2,170 kN (490,000 lbf) |

| 109% thrust | 1,860 kN (420,000 lbf) | 2,280 kN (510,000 lbf) |

Specifying power levels over 100% may seem nonsensical, but there was a logic behind it. The 100% level does not mean the maximum physical power level attainable, rather it was a specification decided on during engine development—the expected rated power level. When later studies indicated the engine could operate safely at levels above 100%, these higher levels became standard. Maintaining the original relationship of power level to physical thrust helps reduce confusion, as it created an unvarying fixed relationship so that test data (or operational data from past or future missions) can be easily compared. If the power level was increased, and that new value was said to be 100%, then all previous data and documentation would either require changing, or cross-checking against what physical thrust corresponded to 100% power level on that date.[8] Engine power level affects engine reliability, with studies indicating the probability of an engine failure increasing rapidly with power levels over 104.5%, which was why power levels above 104.5% were retained for contingency use only.[28]

Incidents

During the course of the Space Shuttle program, a total of 46 RS-25 engines were used (with one extra RS-25D being built but never used). During the 135 missions, for a total of 405 individual engine-missions,[26] Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne reports a 99.95% reliability rate, with the only in-flight SSME failure occurring during Space Shuttle Challenger's STS-51-F mission.[4] The engines, however, did suffer from a number of pad failures (redundant set launch sequencer aborts, or RSLSs) and other issues during the course of the program:

- STS-41-D Discovery – No. 3 engine caused an RSLS shutdown at T−4 seconds due to loss of redundant control on main engine valve, stack rolled back and engine replaced.[33]

- STS-51-F Challenger – No. 2 engine caused an RSLS shutdown at T−3 seconds due to a coolant valve malfunction.[34][35]

- STS-51-F Challenger – No. 1 engine (2023) shutdown at T+5:43 due to faulty temperature sensors, leading to an abort to orbit (although the mission objectives and length were not compromised by the ATO).[22][35]

- STS-55 Columbia – No. 3 engine caused an RSLS shutdown at T−3 seconds due to a leak in its liquid-oxygen preburner check valve.[36]

- STS-51 Discovery – No. 2 engine caused an RSLS shut down at T−3 seconds due to a faulty hydrogen fuel sensor.[37]

- STS-68 Endeavour – No. 3 engine (2032) caused an RSLS shutdown at T−1.9 seconds when a temperature sensor in its HPOTP exceeded its redline.[38]

- STS-93 Columbia – At T+5 seconds, an electrical short disabled one primary and one secondary controller on two of the three engines. In addition, a 0.1-inch diameter, 1-inch long gold-plated pin, used to plug an oxidizer post orifice, came loose inside an engine's main injector and impacted the engine nozzle inner surface, rupturing three hydrogen cooling lines. The resulting three breaches caused a leak resulting in a premature engine shutdown due to increased propellant consumption.[39]

2.3. After Shuttle

Constellation

During the period preceding final Space Shuttle retirement, various plans for the remaining engines were proposed, ranging from them all being kept by NASA, to them all being given away (or sold for US$400,000–800,000 each) to various institutions such as museums and universities.[40] This policy followed changes to the planned configurations of the Constellation program's Ares V cargo-launch vehicle and Ares I crew-launch vehicle rockets, which had been planned to use the RS-25 in their first and second stages respectively.[41] Whilst these configurations had initially seemed worthwhile, as they would use then-current technology following the shuttle's retirement in 2010, the plan had several drawbacks:[41]

- The engines would not be reusable, as they would be permanently attached to the discarded stages.

- Each engine would have to undergo a test firing prior to installation and launch, with refurbishment required following the test.

- It would be expensive, time-consuming, and weight-intensive to convert the ground-started RS-25D to an air-started version for the Ares I second stage.

Following several design changes to the Ares I and Ares V rockets, the RS-25 was to be replaced with a single J-2X engine for the Ares I second stage and six modified RS-68 engines (which was based on both the SSME and Apollo-era J-2 engine) on the Ares V core stage; this meant that the RS-25 would be retired along with the space shuttle fleet.[41] In 2010, however, NASA was directed to halt the Constellation program, and with it development of the Ares I and Ares V, instead focusing on building a new heavy lift launcher.[42]

Space Launch System

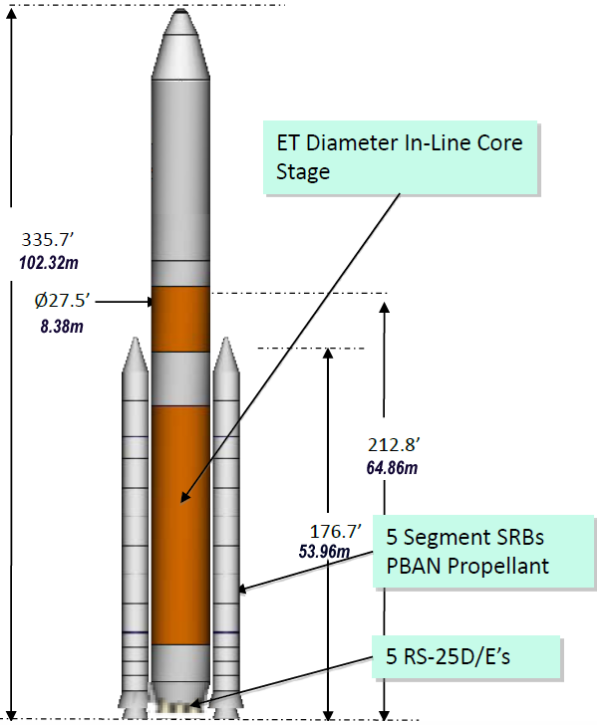

Following the retirement of the Space Shuttle, NASA announced on September 14, 2011, that it would be developing a new launch vehicle, known as the Space Launch System (SLS), to replace the shuttle fleet.[43] The design for the SLS features the RS-25 on its core stage, with different versions of the rocket being installed with between three and five engines.[44][45] The initial flights of the new launch vehicle will make use of flown Block II RS-25D engines, with NASA keeping the remaining such engines in a "purged safe" environment at Stennis Space Center, "along with all of the ground systems required to maintain them."[46][47] In addition to the RS-25Ds, the SLS program will make use of the Main Propulsion Systems from the three remaining orbiters for testing purposes (having been removed as part of the orbiters' decommissioning), with the first two launches (SLS-1 and SLS-2) possibly making use of the MPS hardware from Space Shuttles Atlantis and Endeavour in their core stages.[45][47][48] The SLS's propellants will be supplied to the engines from the rocket's core stage, which will consist of a modified Space Shuttle external tank with the MPS plumbing and engines at its aft, and an interstage structure at the top.[2] Once the remaining RS-25Ds are used up, they are to be replaced with a cheaper, expendable version, currently designated the RS-25E.[2] This engine may be based on one or both of two single-use variants which were studied in 2005, the RS-25E (referred to as the 'Minimal Change Expendable SSME') and the even more simplified RS-25F (referred to as the 'Low Cost Manufacture Expendable SSME'), both of which were under consideration in 2011.[30][49]

XS-1

- On May 24, 2017, DARPA announced that they had selected The Boeing Company to complete design work on the XS-1 program. The technology demonstrator is planned to use an Aerojet Rocketdyne AR-22 engine. The AR-22 is a version of the SSME, with parts sourced from Aerojet Rocketdyne and NASA inventories from early versions of the SSME.[50][51]

- 2015 tests

A test series was planned to determine RS-25 engine performance with: the new engine controller unit; lower liquid oxygen temperatures; greater inlet pressure due to the taller SLS core stage liquid oxygen tank and higher vehicle acceleration; and, more nozzle heating due to the four-engine configuration and its position in-plane with the SLS booster exhaust nozzles. New ablative insulation and heaters were to be tested during the series.[52]

- 9 January

- 28 May

- 11 June - 500 seconds

- 17 July - 535 seconds

- 13 August

- 27 August

Following these series of tests, four more engines are planned to enter a new test cycle.[53]

- 2017 tests

A new series of tests designed to evaluate performance in SLS use cases was initiated in 2017.[54]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Space_Shuttle_main_engine

References

- "Main Propulsion System (MPS)" (PDF). Shuttle Press Kit.com. Boeing, NASA & United Space Alliance. October 6, 1998. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. https://web.archive.org/web/20120204133938/http://www.shuttlepresskit.com/scom/216.pdf. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- Chris Bergin (September 14, 2011). "SLS finally announced by NASA – Forward path taking shape". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2011/09/sls-finally-announced-nasa-forward-path/. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- "Space Shuttle Main Engine Orientation" (PDF). Boeing/Rocketdyne. June 1998. http://www.lpre.de/p_and_w/SSME/SSME_PRESENTATION.pdf. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- null

- "NASA Relies on Copper for Shuttle Engine". Discover Copper Online. Copper Development Association. 1992. http://www.copper.org/publications/newsletters/cutopics/Ct73/shuttle_engine.html. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- Steve Roy (August 2000). "Space Shuttle Main Engine Enhancements". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/news/background/facts/ssme.html. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- null

- Robert E. Biggs (May 1992). "Space Shuttle Main Engine: The First Ten Years". in Stephen E. Doyle. History of Liquid Rocket Engine Development in the United States 1955–1980. AAS History Series. American Astronautical Society. pp. 69–122. ISBN 978-0-87703-350-9. http://www.enginehistory.org/ssme.shtml. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- "Nozzle Design". March 16, 2009. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111002122814/http://www.k-makris.gr/RocketTechnology/Nozzle_Design/nozzle_design.htm. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- "Computers in the Space Shuttle Avionics System". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. NASA. July 15, 2005. https://history.nasa.gov/computers/Ch4-7.html. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- "The future of the shuttle's computers". NASA. July 15, 2005. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/computers/Ch4-8.html. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- "Space Shuttle Main Engine Controllers". NASA. April 4, 2004. http://spaceflight.nasa.gov/shuttle/reference/shutref/orbiter/prop/controllers.html. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- RM Mattox & JB White (November 1981). "Space Shuttle Main Engine Controller" (PDF). NASA. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19820003911_1982003911.pdf. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- "The Cause of the Accident". Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident. NASA. June 6, 1986. https://history.nasa.gov/rogersrep/v1ch4.htm. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- Jim Dumoulin (August 31, 2000). "Main Propulsion System". NASA. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/technology/sts-newsref/sts-mps.html. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Mark Wade. "HG-3". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111115163306/http://www.astronautix.com/engines/hg3.htm. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- NON (January 15, 1970). "F-1A Task Assignment Program". http://archive.org/details/nasa_techdoc_19740077747.

- "MSFC Propulsion Center of Excellence is Built on Solid Foundation". NASA. 1995. http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/saturn_apollo/propulsion_center.html. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- David Baker (April 2011). NASA Space Shuttle. Owners' Workshop Manuals. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-866-6.

- Dwayne Day (April 12, 2010). "A bat outta Hell: the ISINGLASS Mach 22 follow-on to OXCART". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1602/1. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- Fred H. Jue. "Space Shuttle Main Engine: 30 Years of Innovation". Boeing. http://history.msfc.nasa.gov/shuttle/documents/space_shuttle_main_engine_30_years_innovation.pdf. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Wayne Hale & various (January 17, 2012). "An SSME-related request". NASASpaceflight.com. http://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=27783. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- "Countdown 101". NASA. September 17, 2009. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/launch/countdown101.html. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- The level of throttle was initially set to 65%, but, following review of early flight performance, this was increased to a minimum of 67% to reduce fatigue on the MPS. The throttle level was dynamically calculated based on initial launch performance, generally being reduced to a level around 70%.

- John Shannon (June 17, 2009). "Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle" (PDF). http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/361842main_15%20-%20Augustine%20Sidemount%20Final.pdf.

- null

- Chris Bergin (December 3, 2007). "Constellation transition – phased retirement plan for the SSME set". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2007/12/constellation-transition-phased-retirement-plan-for-the-ssme-set/. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "Report of the SSME Assessment Team" (PDF). NASA. January 1993. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19930012456_1993012456.pdf. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- F. Jue and F. Kuck (July 2002). "Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) Options for the Future Shuttle" (DOC). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. http://www.pwrengineering.com/dataresources/SpaceShuttleMainEngine(SSME)OptionsForTheFutureShuttle.doc. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- Ryan Crierie (November 13, 2011). "Reference Spacecraft Engines". http://www.alternatewars.com/BBOW/Space/Reference_Spacecraft_Engines.htm. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- "The Roar of Innovation". NASA. November 6, 2002. https://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2002/06nov_ssme.htm. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- "MSFC and Exploration: Our Path Forward" (PPT). NASA. September 2005. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/ppt/134663main_6976_coalition_MSFC_ESAS_Rollout-092205.ppt.

- Mike Mullane (February 3, 2007). Riding Rockets: The Outrageous Tales of a Space Shuttle Astronaut. Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-7682-5.

- Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001). "51-F". NASA. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-f/mission-51-f.html. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Ben Evans (2007). Space Shuttle Challenger: Ten Journeys into the Unknown. Warwickshire, United Kingdom: Springer-Praxis. ISBN 978-0-387-46355-1.

- Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001). "STS-55". NASA. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/sts-55/mission-sts-55.html. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001). "STS-51". NASA. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/sts-51/mission-sts-51.html. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Jim Dumoulin (June 29, 2001). "STS-68". NASA. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/sts-68/mission-sts-68.html. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Ben Evans (August 30, 2005). Space Shuttle Columbia: Her Missions and Crews. Springer Praxis. ISBN 978-0-387-21517-4.

- Dunn, Marcia (January 15, 2010). "Recession Special: NASA Cuts Space Shuttle Price". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. https://web.archive.org/web/20100118122624/http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/wireStory?id=9574776.

- D Harris & C Bergin (December 26, 2008). "Return to SSME – Ares V undergoes evaluation into potential switch". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2008/12/ssme-ares-v-undergoes-evaluation-potential-switch/. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- "Obama signs Nasa up to new future". BBC News. October 11, 2010. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11518049.

- "NASA Announces Design For New Deep Space Exploration System". NASA. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110921160158/http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2011/sep/HQ_11-301_SLS_Decision.html. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- Chris Bergin (October 4, 2011). "SLS trades lean towards opening with four RS-25s on the core stage". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2011/10/sls-trades-opening-four-rs-25s-core-stage/. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- Chris Bergin (January 13, 2012). "SSME family prepare for SLS core stage role following Shuttle success". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/01/ssme-family-sls-core-stage-role-shuttle-success/. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- Carreau, Mark (March 29, 2011). "NASA Will Retain Block II SSMEs". Aviation Week. http://www.aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_channel.jsp?channel=space&id=news/asd/2011/03/29/08.xml&headline=NASA%20Will%20Retain%20Block%20II%20SSMEs. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

- Chris Bergin (January 22, 2012). "Engineers begin removing orbiter MPS components for donation to SLS". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2012/01/engineers-removing-orbiter-mps-components-donation-sls/. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- Chris Bergin (September 20, 2011). "PRCB managers recommend Atlantis and Endeavour become SLS donors". NASASpaceflight.com. http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2011/09/prcb-recommend-atlantis-endeavour-become-sls-donors/. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- P. McConnaughey (February 2011). "NASA Technology Area 1: Launch Propulsion Systems". NASA. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20110009917_2011009273.pdf. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "DARPA Picks Design for Next-Generation Spaceplane" (in en-US). https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2017-05-24.

- "Aerojet Rocketdyne Selected As Main Propulsion Provider for Boeing and DARPA Experimental Spaceplane | Aerojet Rocketdyne" (in en). http://www.rocket.com/article/aerojet-rocketdyne-selected-main-propulsion-provider-boeing-and-darpa-experimental.

- RS-25 Engine Fires Up for Third Test in Series, Kim Henry, Marshall Space Flight Center, in SpaceDaily.com, 17 June 2015, accessed 18 June 2015 http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/RS_25_Engine_Fires_Up_for_Third_Test_in_Series_999.html

- "Pedal to the Metal – RS-25 Engine Revs Up Again". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/exploration/systems/sls/multimedia/pedal-to-the-metal-rs-25-engine-revs-up-again.html.

- "NASA Stennis RS-25 landing page". NASA Stennis. https://www.nasa.gov/centers/stennis/rs-25/index.html. Retrieved 14 October 2017.