Anthocyanins are secondary metabolites and distributed in flowers, fruits and vegetables. They provide various colours such as red, pink, blue and purple. To date, more than 700 anthocyanins have been identified in nature. These anthocyanins have been associated with many health benefits through different mechanisms. Some of the therapeutic potentials of anthocyanins and their mechanisms of action are highlighted.

- anthocyanins

- oxidative stress

- gut microbiota

- inflammation

1. Mechanisms of Action of Anthocyanins in Disease

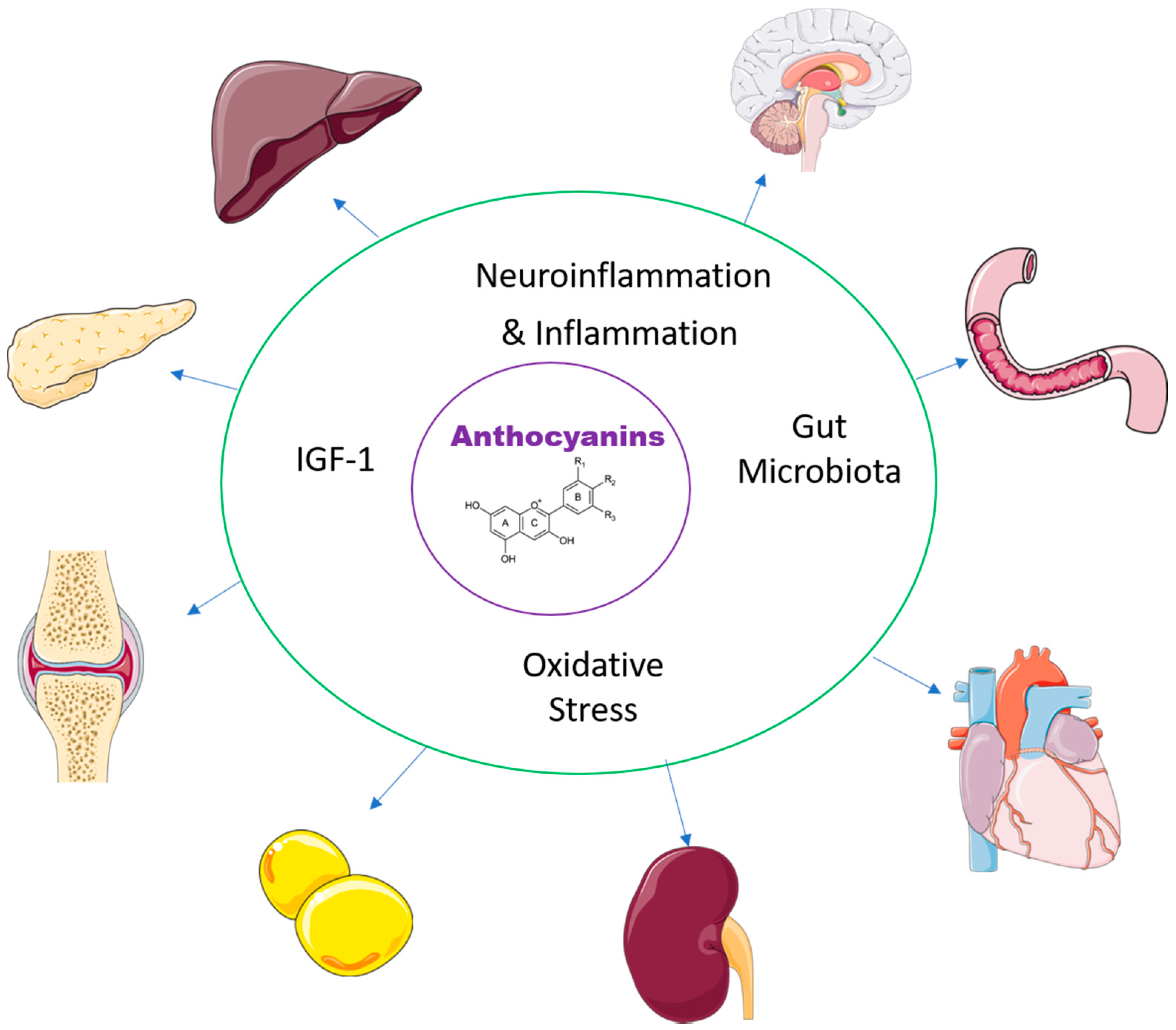

Functional foods containing anthocyanins have been studied for health benefits but most of these studies have been in cells or animal models of human disease, rather than in human clinical trials. In this section, the recent literature has been reviewed to summarise the potential mechanisms of anthocyanins in chronic diseases such as changes in the gut microbiota, decreased oxidative stress, decreased inflammation and increasing insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) (Figure 1). The multiple changes in chronic disease states and the interactions between these mechanisms indicate that it is unlikely that any one mechanism is responsible for therapeutic responses in any particular disease state. However, an improved understanding of these mechanisms may allow more logical therapeutic choices to be made.

Figure 1. Effects of anthocyanins in the major organs.

1.1. Gut Microbiota

After ingestion, functional foods first interact with the microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract, collectively known as the gut microbiota. This complex micro-ecosystem is essential for many functions including digestion, regulation of the immune system and stabilising the intestinal barrier. Nutrients change the microbiota and intestinal barrier function, for example by the synthesis of folate to increase methylation and so change gastrointestinal function by epigenetic modifications [106]. Further, the gut microbiota may metabolise the functional foods. These microbial metabolites may produce physiological responses in the intestine and after absorption and distribution in the body. However, the metabolites may also lead to the development of chronic low-grade inflammation both in the intestine and throughout the body [107]. The bacterial metabolites that influence the immune signalling pathways include short-chain fatty acids, indole and indole acid derivatives, choline, bile acids, N-acyl amides, vitamins and polyamines [108]. Under physiological conditions when the inflammatory processes have achieved their aims, the resolution of inflammation is mediated by pro-resolving lipid mediators produced in damaged tissues, giving a further potential intervention to reduce inflammation through activating these pro-resolving pathways [109]. Changes in the gut microbiota have been suggested as being responsible for a wide range of diseases such as gastrointestinal diseases including inflammatory bowel disease [110], neurological disorders [111] including schizophrenia [112] and Parkinson’s disease [113], metabolic syndrome [114], cardiovascular disease [115], chronic kidney disease [116] and type 2 diabetes [117], providing a potential target for the management of these diseases.

Anthocyanins can be absorbed in the stomach by specific transporters such as sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter 1, metabolised by the gut microbiota in the colon and modified by phase I and II metabolic enzymes in liver cells followed by enterohepatic circulation before distribution of anthocyanins and derivatives and accumulation in tissues [118]. These metabolites could independently alter organ structure and function in chronic disease states; for example, a major metabolite of anthocyanins, protocatechuic acid, has demonstrated antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties [119]. Concentrations in studies with isolated cells were usually around 10–100 μM while daily doses in rodents were around 10–100 mg/kg. Pharmacokinetic studies in humans after an oral dose of 500 mg cyanidin 3-glucoside show that serum concentrations of protocatechuic acid and its metabolites peaked at around 0.1 μM but were present in the circulation for longer and at higher concentrations than the parent anthocyanin [120]. In addition, protocatechuic acid may decrease cognitive and behavioural impairment, neuroinflammation and excessive production of reactive oxygen species [121].

Anthocyanins also act as prebiotics to modify the microbiota, in particular enhancing Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp. [122]. Both effects potentially lead to cardioprotective and neuroprotective responses and decreased bone loss in the ageing population [123]. Regulation of the gut microbiota by polyphenols, including anthocyanins, may reduce kidney injury to treat pre-existing chronic kidney disease [124]. Anthocyanins such as cyanidin 3-glucoside may be potential prebiotics, as purified cyanidin 3-glucoside (7.2 mg/kg/day) and anthocyanin-containing Saskatoon berry (8.0 mg/kg/day) administration for 11 weeks reduced high-fat high-sucrose diet-induced changes in the gut microbiota in mice [125].

1.2. Oxidative Stress

Low concentrations of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, nitric oxide and peroxynitrate are important in the defence against pathogenic microorganisms. Higher concentrations cause cellular damage leading to cell death by actions on DNA, proteins and lipids, a condition known as oxidative/nitrative stress. Oxidative stress is a key activator of disease onset and progression, overlapping with inflammation, providing the rationale for the effectiveness of anthocyanins in obesity, cardiovascular and neurological diseases [126].

Mitochondria are the major source of intracellular ROS as leakage of electrons through the respiratory chain. Accumulation of ROS in mitochondria disrupts normal function leading to depolarisation of the mitochondrial membrane. In high-energy-consuming cells such as cardiomyocytes, impaired mitochondrial activity will interfere with glucose and fatty acid metabolism leading to cardiomyopathy. Anthocyanins and their metabolite, protocatechuic acid, could decrease mitochondrial ROS concentrations and so reduce damage [127]. Further, some anthocyanins including cyanidin 3-glucoside may form an additional transport chain in damaged mitochondria as electron acceptors at Complex I to reduce cytochrome C and increase ATP production [128].

An additional target to reduce oxidative stress is DNA methylation as it is important in the long-term regulation of gene expression. Plant-derived antioxidants such as anthocyanins may be involved in epigenetic mechanisms to reverse aberrant methylation and oxidative stress without changing the underlying gene sequences [129]. These diseases occur through the regulation of epigenetic enzymes and chromatin remodelling complexes. Potential therapeutic targets include diseases that are increased in patients with metabolic syndrome, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease [129].

Further, mitochondrial DNA may be displaced from cells by cell-death-triggering stressors into extracellular compartments. This defective mitochondrial quality control may increase low-grade chronic inflammation by NLRP3 and other pathways [130]. This could provide pathways for compounds such as anthocyanins to improve mitochondrial function and decrease inflammation.

1.3. Inflammation

Low-grade chronic inflammation underlies many chronic systemic diseases, especially age-related decline and metabolic disorders [131,132,133,134,135,136]. In obesity, it is characterised by the secretion of a complex range of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines from expanding adipocytes in visceral adipose tissue known as adipokines that initiate and sustain the inflammation [137]. These adipokines impact remote organ function to produce the complications of cardiometabolic disease [138].

The bacteria in the gut microbiota regulate the permeability of the intestines with some species promoting a “leaky gut”. This allows microbial metabolites and components of the bacteria, such as lipopolysaccharides, to enter the circulation and start an inflammatory reaction by the release of cytokines. Further, gut microbiota allow the conversion of complex carbohydrates, not digested by the host, to short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate which are absorbed and may be anti-inflammatory [139]. As increased inflammation is associated with many diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, inflammatory bowel disease and cancer, understanding the role of the gut microbiota in these diseases is important.

In obesity, increased inflammatory responses occur with pro-inflammatory macrophages accumulating in adipose tissue, possibly with hypoxia as the initiating event leading to greater expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α and increased inflammatory responses in the liver, pancreatic islets and gastrointestinal tract [140]. Adipose tissue inflammation decreases remote organ function, considered causative for the complications of obesity [138]. The role of the hypothalamus in the regulation of energy homeostasis is well-known. The inflammatory activation of glial cells in the hypothalamus leads to changes in feeding habits, thermogenesis and adipokine signalling, leading to metabolic disorders [141]. Further, maternal obesity and inflammation may lead to metabolic reprogramming in the foetus, which could influence both childhood and adult body weight and composition, thus increasing the risk of transgenerational transmission of obesity [142].

The anti-inflammatory responses to anthocyanins have been shown in many in vivo and in vitro systems; further, anthocyanins regulate pro-inflammatory markers in both healthy and chronic disease states [143]. There are many mechanisms for the anti-inflammatory effects of anthocyanins that could be applicable in chronic inflammatory diseases, including inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory factors, reducing TLR4 expression, inhibition of the NF-κB and MAPK signalling pathways, and reducing the production of NO, ROS and prostaglandin E2 [144].

Reducing inflammation in the brain may play a role in anthocyanin-induced changes in chronic disease. Prolonged neuroinflammation damages brain function, possibly causing and accelerating long-term neurodegenerative diseases including dementia [145]. The gut-microbiota-brain axis allowing bidirectional communication is important in maintaining the homeostasis of the central nervous system as well as the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, much recent research has focused on the relationships between gut microbiota and neurological disorders such as schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and ischaemic stroke, which involve the death of vulnerable populations of neurons [146]. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota has been associated with the progression of both systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation [147]. Mediators of neuroinflammation include microglia, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes as well as damaged and dysfunctional mitochondria [148].

Anthocyanins and their metabolites produce neuroprotective activities by decreasing neuroinflammation, preventing excitotoxicity, preventing aggregation of proteins, activating pro-survival pathways while inhibiting pro-apoptotic pathways and improving axonal health [149,150]. The wide range of potential mechanisms to overcome neurotoxicity with anthocyanins such as cyanidin glucoside includes suppression of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation, amelioration of cellular degeneration, activation of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor signalling and restoration of Ca2+ and Zn2+ homeostasis [151]. Blueberry extract (150 mg/kg/day) containing anthocyanins promoted neuronal autophagy to decrease neuronal damage in transgenic APP/PS1 mice with mutations associated with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Further, protocatechuic acid may be the major metabolite producing neuroprotection [152]. Possible changes in amino acid metabolism have been suggested as the mechanism of improved attention, feelings of alertness and mental fatigue after 3 months’ treatment with tart cherries containing anthocyanins and other polyphenols in middle-aged adults [153]. These changes could be beneficial if they can be translated to patients with neurological or neurodegenerative diseases.

However, most studies have been performed in cell culture or in pre-clinical animal models. Thus, the roles of anthocyanins and their metabolites in existing neurodegenerative diseases in humans where significant neuronal loss has already occurred are uncertain but possible. Targeting neuroinflammation with anthocyanins is therefore a promising strategy in the treatment of neurological disease [150] although the translation of results from animal models to patients with neurological disease requires further research. Further, direct pharmacological actions in the brain of orally administered anthocyanins require that anthocyanins pass through the blood–brain barrier, yet the permeability of anthocyanins has been shown to be low [154]. This suggests that the major reason for decreased neurotoxicity with anthocyanins could be that changes in gut microbiota lead to decreased neuroinflammation.

1.4. IGF-1

The neuropeptide IGF-1 has important roles in the development and maturation of the brain [155]. Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP), a neuropeptide formed from the N-terminal tripeptide fragment of IGF-1, activates and normalises IGF-1 essential for body growth, neurological function and lifespan [156,157]. However, IGF-1 may play opposing roles in the ageing brain, where chronic neurodegenerative, cardiovascular and metabolic diseases are more likely to have a pathological effect [158]. The study of the interactions of IGF-1 and anthocyanins is relatively recent but it is providing a potential mechanism for their therapeutic benefits.

The interaction of cGP with bound/free IGF-1 may mediate the therapeutic benefits of anthocyanins in reducing blood pressure and improving cognitive health [159]. cGP has a higher binding affinity to the IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) than IGF-1 itself, thereby increasing the free concentrations of active IGF-1 in the plasma. IGF-1 reduced hypertension in pre-clinical models of hypertension [160]. This could account for the normalisation of blood pressure in obese adults with mild hypertension [161].

Decreased peripheral and cerebrospinal fluid IGF-1 concentrations could be a potential marker for the cognitive decline and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. In the brain of Alzheimer’s disease patients, bioavailable IGF-1 deficiency was shown with increases in bound IGFBP-3 and bound cGP [162]. As IGF-1 is involved in synaptogenesis, increased bioavailable IGF-1/cGP could improve brain function in Alzheimer’s disease. Consumption of blackcurrant supplement containing 35% anthocyanins at a dose of ~600 mg daily increased cGP concentrations in both the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in humans, showing that the lipophilic nature of cGP enabled rapid transfer across the blood–brain barrier [163]. This could support the hypothesis that anthocyanins are effective both in reducing blood pressure and improving brain function by increasing IGF-1 and cGP in the brain. The mechanisms through which dietary anthocyanins increase cGP in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid are currently under investigation. One study showed that blackcurrant juice contained both anthocyanins and cGP [163].

2. Therapeutic Actions of Anthocyanins in Chronic Diseases

2.1. Delaying Cognitive Decline

2.2. Modulating Neurodegenerative and Neurological Diseases

2.3. Protecting the Liver

2.4. Protecting the Heart and Blood Vessels

2.5. Maintaining Glucose Homeostasis

2.6. Protecting the Kidneys

2.7. Decreasing Obesity

2.8. Increasing Bone Repair

2.9. Protecting and Repairing the Gastrointestinal Tract

2.10. Moderating Physiological Changes in Exercise

2.11. Protection against Cancer

2.12. Moderating Ageing

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14102161

References

- Tangestani Fard, M.; Stough, C. A review and hypothesized model of the mechanisms that underpin the relationship between inflammation and cognition in the elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 56.

- Yeh, T.S.; Yuan, C.; Ascherio, A.; Rosner, B.A.; Willett, W.C.; Blacker, D. Long-term dietary flavonoid intake and subjective cognitive decline in US men and women. Neurology 2021, 97, e1041–e1056.

- McNamara, R.K.; Kalt, W.; Shidler, M.D.; McDonald, J.; Summer, S.S.; Stein, A.L.; Stover, A.N.; Krikorian, R. Cognitive response to fish oil, blueberry, and combined supplementation in older adults with subjective cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 64, 147–156.

- Boespflug, E.L.; Eliassen, J.C.; Dudley, J.A.; Shidler, M.D.; Kalt, W.; Summer, S.S.; Stein, A.L.; Stover, A.N.; Krikorian, R. Enhanced neural activation with blueberry supplementation in mild cognitive impairment. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 297–305.

- Kent, K.; Charlton, K.; Roodenrys, S.; Batterham, M.; Potter, J.; Traynor, V.; Gilbert, H.; Morgan, O.; Richards, R. Consumption of anthocyanin-rich cherry juice for 12 weeks improves memory and cognition in older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 333–341.

- Miller, K.; Feucht, W.; Schmid, M. Bioactive compounds of strawberry and blueberry and their potential health effects based on human intervention studies: A brief overview. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1510.

- Marques, C.; Fernandes, I.; Meireles, M.; Faria, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Mateus, N.; Calhau, C. Gut microbiota modulation accounts for the neuroprotective properties of anthocyanins. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11341.

- Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, F.; Tong, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; He, H.; Xu, R.; Ma, Y.; Huang, C. Neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins and its major component cyanidin-3-O-glucoside (C3G) in the central nervous system: An outlined review. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 858, 172500.

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303.

- Talebi, S.; Ghoreishy, S.M.; Jayedi, A.; Travica, N.; Mohammadi, H. Dietary antioxidants and risk of Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 2022.

- Winter, A.N.; Bickford, P.C. Anthocyanins and their metabolites as therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 333.

- Castilla-Cortázar, I.; Aguirre, G.A.; Femat-Roldán, G.; Martín-Estal, I.; Espinosa, L. Is insulin-like growth factor-1 involved in Parkinson’s disease development? J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 70.

- Fan, D.; Alamri, Y.; Liu, K.; MacAskill, M.; Harris, P.; Brimble, M.; Dalrymple-Alford, J.; Prickett, T.; Menzies, O.; Laurenson, A.; et al. Supplementation of blackcurrant anthocyanins increased cyclic glycine-proline in the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson patients: Potential treatment to improve insulin-like growth factor-1 function. Nutrients 2018, 10, 714.

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: Where do we go from here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157–172.

- Khan, M.S.; Ikram, M.; Park, J.S.; Park, T.J.; Kim, M.O. Gut microbiota, its role in induction of alzheimer’s disease pathology, and possible therapeutic interventions: Special focus on anthocyanins. Cells 2020, 9, 853.

- Shukla, P.K.; Delotterie, D.F.; Xiao, J.; Pierre, J.F.; Rao, R.; McDonald, M.P.; Khan, M.M. Alterations in the gut-microbial-inflammasome-brain axis in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cells 2021, 10, 779.

- Shen, H.; Guan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, C.; Tan, Z.; Zhai, L.; Hao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Han, C. New mechanism of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: The activation of NLRP3 inflammasome mediated by gut microbiota. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 109884.

- Wang, X.; Sun, G.; Feng, T.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, T.; Xie, Z.; Chu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. Sodium oligomannate therapeutically remodels gut microbiota and suppresses gut bacterial amino acids-shaped neuroinflammation to inhibit Alzheimer’s disease progression. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 787–803.

- Xiao, S.; Chan, P.; Wang, T.; Hong, Z.; Wang, S.; Kuang, W.; He, J.; Pan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ji, Y.; et al. A 36-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3 clinical trial of sodium oligomannate for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s dementia. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 62.

- Henriques, J.F.; Serra, D.; Dinis, T.C.P.; Almeida, L.M. The anti-neuroinflammatory role of anthocyanins and their metabolites for the prevention and treatment of brain disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8653.

- Agarwal, P.; Holland, T.M.; Wang, Y.; Bennett, D.A.; Morris, M.C. Association of strawberries and anthocyanidin intake with Alzheimer’s dementia risk. Nutrients 2019, 11, 3060.

- van Es, M.A.; Hardiman, O.; Chio, A.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Pasterkamp, R.J.; Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2084–2098.

- Koza, L.A.; Winter, A.N.; Holsopple, J.; Baybayon-Grandgeorge, A.N.; Pena, C.; Olson, J.R.; Mazzarino, R.C.; Patterson, D.; Linseman, D.A. Protocatechuic acid extends survival, improves motor function, diminishes gliosis, and sustains neuromuscular junctions in the hSOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1824.

- Cásedas, G.; Les, F.; López, V. Anthocyanins: Plant pigments, food ingredients or therapeutic agents for the CNS? A mini-review focused on clinical trials. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 1790–1798.

- Losso, J.N.; Finley, J.W.; Karki, N.; Liu, A.G.; Prudente, A.; Tipton, R.; Yu, Y.; Greenway, F.L. Pilot study of the tart cherry juice for the treatment of insomnia and investigation of mechanisms. Am. J. Ther. 2018, 25, e194–e201.

- Enjoji, M.; Kohjima, M.; Nakamuta, M. Lipid metabolism and the liver. In The Liver in Systemic Diseases; Ohira, H., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 105–122.

- Chang, J.-J.; Hsu, M.-J.; Huang, H.-P.; Chung, D.-J.; Chang, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-J. Mulberry anthocyanins inhibit oleic acid induced lipid accumulation by reduction of lipogenesis and promotion of hepatic lipid clearance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 6069–6076.

- Long, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Delphinidin-3-sambubioside from Hibiscus sabdariffa. L attenuates hyperlipidemia in high fat diet-induced obese rats and oleic acid-induced steatosis in HepG2 cells. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 3837–3849.

- Powell, E.E.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Rinella, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2212–2224.

- Mehmood, A.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Pan, F.; Hao, S.; Zhang, H.; Iftikhar, A.; Usman, M. Dietary anthocyanins as potential natural modulators for the prevention and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A comprehensive review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110180.

- Zhang, P.W.; Chen, F.X.; Li, D.; Ling, W.H.; Guo, H.H. A CONSORT-compliant, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of purified anthocyanin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine 2015, 94, e758.

- Zhou, F.; She, W.; He, L.; Zhu, J.; Gu, L. The effect of anthocyanins supplementation on liver enzymes among patients with metabolic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 53–61.

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237.

- Kimble, R.; Keane, K.M.; Lodge, J.K.; Howatson, G. Dietary intake of anthocyanins and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3032–3043.

- Xu, L.; Tian, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y. Anthocyanins, anthocyanin-rich berries, and cardiovascular risks: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 randomized controlled trials and 15 prospective cohort studies. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 747884.

- Sandoval-Ramírez, B.A.; Catalán, Ú.; Llauradó, E.; Valls, R.M.; Salamanca, P.; Rubió, L.; Yuste, S.; Solà, R. The health benefits of anthocyanins: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and controlled clinical trials. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1515–1530.

- Bhaswant, M.; Brown, L.; Mathai, M.L. Queen Garnet plum juice and raspberry cordial in mildly hypertensive obese or overweight subjects: A randomized, double-blind study. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 119–126.

- Shan, X.; Lv, Z.Y.; Yin, M.J.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q.N. The protective effect of cyanidin-3-glucoside on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8880141.

- Bäck, M.; Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Tabas, I.; Öörni, K.; Kovanen, P.T. Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: Mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 389–406.

- Garcia, C.; Blesso, C.N. Antioxidant properties of anthocyanins and their mechanism of action in atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 152–166.

- Amin, H.P.; Czank, C.; Raheem, S.; Zhang, Q.; Botting, N.P.; Cassidy, A.; Kay, C.D. Anthocyanins and their physiologically relevant metabolites alter the expression of IL-6 and VCAM-1 in CD40L and oxidized LDL challenged vascular endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1095–1106.

- Aboonabi, A.; Singh, I.; Rose’ Meyer, R. Cytoprotective effects of berry anthocyanins against induced oxidative stress and inflammation in primary human diabetic aortic endothelial cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 317, 108940.

- Duan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, R.; Wang, D.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Suppression of apoptosis in vascular endothelial cell, the promising way for natural medicines to treat atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 168, 105599.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside attenuates endothelial cell dysfunction by modulating miR-204-5p/SIRT1-mediated inflammation and apoptosis. Biofactors 2020, 46, 803–812.

- Festa, J.; Da Boit, M.; Hussain, A.; Singh, H. Potential benefits of berry anthocyanins on vascular function. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2100170.

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent research on the health benefits of blueberries and their anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236.

- do Rosario, V.A.; Chang, C.; Spencer, J.; Alahakone, T.; Roodenrys, S.; Francois, M.; Weston-Green, K.; Hölzel, N.; Nichols, D.S.; Kent, K.; et al. Anthocyanins attenuate vascular and inflammatory responses to a high fat high energy meal challenge in overweight older adults: A cross-over, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 879–889.

- Santhakumar, A.B.; Kundur, A.R.; Fanning, K.; Netzel, M.; Stanley, R.; Singh, I. Consumption of anthocyanin-rich Queen Garnet plum juice reduces platelet activation related thrombogenesis in healthy volunteers. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 11–22.

- Tinajero, M.G.; Malik, V.S. An update on the epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: A global perspective. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 50, 337–355.

- Bellary, S.; Kyrou, I.; Brown, J.E.; Bailey, C.J. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in older adults: Clinical considerations and management. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 534–548.

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Buckley, J.; Cicek, M.; Gregg, E.W. The changing nature of mortality and morbidity in patients with diabetes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 50, 357–368.

- Nauck, M.A.; Wefers, J.; Meier, J.J. Treatment of type 2 diabetes: Challenges, hopes, and anticipated successes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 525–544.

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: Results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039.

- Da Porto, A.; Cavarape, A.; Colussi, G.; Casarsa, V.; Catena, C.; Sechi, L.A. Polyphenols rich diets and risk of type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1445.

- Cao, H.; Ou, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Szkudelski, T.; Delmas, D.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J. Dietary polyphenols and type 2 diabetes: Human study and clinical trial. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3371–3379.

- Kim, Y.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Polyphenols and glycemic control. Nutrients 2016, 8, 17.

- Hanhineva, K.; Törrönen, R.; Bondia-Pons, I.; Pekkinen, J.; Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, H.; Poutanen, K. Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1365–1402.

- Putta, S.; Yarla, N.S.; Kumar, K.E.; Lakkappa, D.B.; Kamal, M.A.; Scotti, L.; Scotti, M.T.; Ashraf, G.M.; Rao, B.S.B.; Kumari, S.D.; et al. Preventive and therapeutic potentials of anthocyanins in diabetes and associated complications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5347–5371.

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhou, Q. Targets and mechanisms of dietary anthocyanins to combat hyperglycemia and hyperuricemia: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1119–1143.

- Yan, F.; Dai, G.; Zheng, X. Mulberry anthocyanin extract ameliorates insulin resistance by regulating PI3K/AKT pathway in HepG2 cells and db/db mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 36, 68–80.

- Tian, J.-L.; Si, X.; Shu, C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Tan, H.; Zang, Z.-H.; Zhang, W.-J.; Xie, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, B. Synergistic effects of combined anthocyanin and metformin treatment for hyperglycemia in vitro and in vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1182–1195.

- Morissette, A.; Kropp, C.; Songpadith, J.P.; Junges Moreira, R.; Costa, J.; Mariné-Casadó, R.; Pilon, G.; Varin, T.V.; Dudonné, S.; Boutekrabt, L.; et al. Blueberry proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins improve metabolic health through a gut microbiota-dependent mechanism in diet-induced obese mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E965–E980.

- Huda, M.N.; Kim, M.; Bennett, B.J. Modulating the microbiota as a therapeutic intervention for type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 632335.

- Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Ling, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Ma, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, J. Effect of anthocyanins supplementation on serum IGFBP-4 fragments and glycemic control in patients with fasting hyperglycemia: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 3395–3404.

- Solverson, P. Anthocyanin bioactivity in obesity and diabetes: The essential role of glucose transporters in the gut and periphery. Cells 2020, 9, 2515.

- Cremonini, E.; Daveri, E.; Mastaloudis, A.; Oteiza, P.I. (–)-Epicatechin and anthocyanins modulate GLP-1 metabolism: Evidence from C57BL/6J mice and GLUTag cells. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1497–1506.

- Lv, J.C.; Zhang, L.X. Prevalence and disease burden of chronic kidney disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1165, 3–15.

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2021, 398, 786–802.

- Hobby, G.P.; Karaduta, O.; Dusio, G.F.; Singh, M.; Zybailov, B.L.; Arthur, J.M. Chronic kidney disease and the gut microbiome. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2019, 316, F1211–F1217.

- Stavropoulou, E.; Kantartzi, K.; Tsigalou, C.; Aftzoglou, K.; Voidarou, C.; Konstantinidis, T.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Thodis, E.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Microbiome, immunosenescence, and chronic kidney disease. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 661203.

- Usuda, H.; Okamoto, T.; Wada, K. Leaky gut: Effect of dietary fiber and fats on microbiome and intestinal barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7613.

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Ławiński, J.; Olszewski, R.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. The impact of CKD on uremic toxins and gut microbiota. Toxins 2021, 13, 252.

- Afsar, B.; Afsar, R.E.; Ertuglu, L.A.; Covic, A.; Kanbay, M. Nutrition, immunology, and kidney: Looking beyond the horizons. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 69–81.

- Bao, N.; Chen, F.; Dai, D. The regulation of host intestinal microbiota by polyphenols in the development and prevention of chronic kidney disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2981.

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298.

- Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, C.; Sun, J.; Tian, L.; Chen, W.; Bai, W. The target cells of anthocyanins in metabolic syndrome. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 921–946.

- Park, S.; Choi, M.; Lee, M. Effects of anthocyanin supplementation on reduction of obesity criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2121.

- Jung, A.J.; Sharma, A.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.J. Efficacy of black rice extract on obesity in obese postmenopausal women: A 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled preliminary clinical trial. Menopause 2021, 28, 1391–1399.

- Gomes, J.V.P.; Rigolon, T.C.B.; Souza, M.; Alvarez-Leite, J.I.; Lucia, C.M.D.; Martino, H.S.D.; Rosa, C.O.B. Antiobesity effects of anthocyanins on mitochondrial biogenesis, inflammation, and oxidative stress: A systematic review. Nutrition 2019, 66, 192–202.

- Pérez-Torres, I.; Castrejón-Téllez, V.; Soto, M.E.; Rubio-Ruiz, M.E.; Manzano-Pech, L.; Guarner-Lans, V. Oxidative stress, plant natural antioxidants, and obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1786.

- Jayarathne, S.; Stull, A.J.; Park, O.H.; Kim, J.H.; Thompson, L.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Protective effects of anthocyanins in obesity-associated inflammation and changes in gut microbiome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900149.

- Canfora, E.E.; Meex, R.C.R.; Venema, K.; Blaak, E.E. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 261–273.

- Lee, Y.-M.; Yoon, Y.; Yoon, H.; Park, H.-M.; Song, S.; Yeum, K.-J. Dietary anthocyanins against obesity and inflammation. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1089.

- Tucakovic, L.; Colson, N.; Santhakumar, A.B.; Kundur, A.R.; Shuttleworth, M.; Singh, I. The effects of anthocyanins on body weight and expression of adipocyte’s hormones: Leptin and adiponectin. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 45, 173–180.

- Abramoff, B.; Caldera, F.E. Osteoarthritis: Pathology, diagnosis, and treatment options. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 104, 293–311.

- Li, H.; Xiao, Z.; Quarles, L.D.; Li, W. Osteoporosis: Mechanism, molecular target and current status on drug development. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 1489–1507.

- Basu, A.; Schell, J.; Scofield, R.H. Dietary fruits and arthritis. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 70–77.

- Jiang, C.; Sun, Z.M.; Hu, J.N.; Jin, Y.; Guo, Q.; Xu, J.J.; Chen, Z.X.; Jiang, R.H.; Wu, Y.S. Cyanidin ameliorates the progression of osteoarthritis via the Sirt6/NF-κB axis in vitro and in vivo. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 5873–5885.

- Chuntakaruk, H.; Kongtawelert, P.; Pothacharoen, P. Chondroprotective effects of purple corn anthocyanins on advanced glycation end products induction through suppression of NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1895.

- John, O.D.; Mouatt, P.; Prasadam, I.; Xiao, Y.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. The edible native Australian fruit, Davidson’s plum (Davidsonia pruriens), reduces symptoms in rats with diet-induced metabolic syndrome. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 204–215.

- Mao, W.; Huang, G.; Chen, H.; Xu, L.; Qin, S.; Li, A. Research progress of the role of anthocyanins on bone regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 773660.

- Ren, Z.; Raut, N.A.; Lawal, T.O.; Patel, S.R.; Lee, S.M.; Mahady, G.B. Peonidin-3-O-glucoside and cyanidin increase osteoblast differentiation and reduce RANKL-induced bone resorption in transgenic medaka. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 6255–6269.

- Raut, N.; Wicks, S.M.; Lawal, T.O.; Mahady, G.B. Epigenetic regulation of bone remodeling by natural compounds. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 147, 104350.

- Hao, X.; Shang, X.; Liu, J.; Chi, R.; Zhang, J.; Xu, T. The gut microbiota in osteoarthritis: Where do we stand and what can we do? Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 42.

- Guan, Z.; Jia, J.; Zhang, C.; Sun, T.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, W.; Leng, H.; Song, C. Gut microbiome dysbiosis alleviates the progression of osteoarthritis in mice. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 3159–3174.

- Li, S.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, F.; Yang, H.; Shi, Q.; Meng, B. Gut microbiome and osteoporosis: A review. Bone Joint. Res. 2020, 9, 524–530.

- Kaplan, G.G.; Windsor, J.W. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 56–66.

- Aldars-García, L.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J.P. Systematic review: The gut microbiome and its potential clinical application in inflammatory bowel disease. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 977.

- Deleu, S.; Machiels, K.; Raes, J.; Verbeke, K.; Vermeire, S. Short chain fatty acids and its producing organisms: An overlooked therapy for IBD? eBioMedicine 2021, 66, 103293.

- Li, S.; Wu, B.; Fu, W.; Reddivari, L. The anti-inflammatory effects of dietary anthocyanins against ulcerative colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2588.

- Cheng, Z.; Si, X.; Tan, H.; Zang, Z.; Tian, J.; Shu, C.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Meng, X.; et al. Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside and its phenolic metabolites ameliorate intestinal diseases via modulating intestinal mucosal immune system: Potential mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021.

- Goodman, C.; Lyon, K.N.; Scotto, A.; Smith, C.; Sebrell, T.A.; Gentry, A.B.; Bala, G.; Stoner, G.D.; Bimczok, D. A high-throughput metabolic microarray assay reveals antibacterial effects of black and red raspberries and blackberries against Helicobacter pylori infection. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 845.

- Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.H.; Park, M.; Woo, H.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Tharmalingam, N.; Seo, W.D.; Kim, J.B. Regulatory effects of black rice extract on Helicobacter pylori infection-induced apoptosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700586.

- Fagundes, F.L.; Pereira, Q.C.; Zarricueta, M.L.; Dos Santos, R.C. Malvidin protects against and repairs peptic ulcers in mice by alleviating oxidative stress and inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3312.

- Ghattamaneni, N.K.R.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. Cyanidin 3-glucoside from Queen Garnet plums and purple carrots attenuates DSS-induced inflammatory bowel disease in rats. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 194–203.

- Ghattamaneni, N.K.R.; Panchal, S.K.; Brown, L. An improved rat model for chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 149–155.

- Copetti, C.L.K.; Diefenthaeler, F.; Hansen, F.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Di Pietro, P.F. Fruit-derived anthocyanins: Effects on cycling-induced responses and cycling performance. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 387.

- Kimble, R.; Jones, K.; Howatson, G. The effect of dietary anthocyanins on biochemical, physiological, and subjective exercise recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021.

- Bars-Cortina, D.; Sakhawat, A.; Piñol-Felis, C.; Motilva, M.J. Chemopreventive effects of anthocyanins on colorectal and breast cancer: A review. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 241–258.

- Shi, N.; Chen, X.; Chen, T. Anthocyanins in colorectal cancer prevention review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1600.

- Chen, J.; Xu, B.; Sun, J.; Jiang, X.; Bai, W. Anthocyanin supplement as a dietary strategy in cancer prevention and management: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021.

- Medic, N.; Tramer, F.; Passamonti, S. Anthocyanins in colorectal cancer prevention. A systematic review of the literature in search of molecular oncotargets. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 675.

- Lin, B.-W.; Gong, C.-C.; Song, H.-F.; Cui, Y.-Y. Effects of anthocyanins on the prevention and treatment of cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1226–1243.

- Hair, R.; Sakaki, J.R.; Chun, O.K. Anthocyanins, microbiome and health benefits in aging. Molecules 2021, 26, 537.

- Nomi, Y.; Iwasaki-Kurashige, K.; Matsumoto, H. Therapeutic effects of anthocyanins for vision and eye health. Molecules 2019, 24, 3311.

- Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Alawadh, S.H.; Bouazzaoui, A.; Alhowail, A.H.; Mohammed, H.A. Anthocyanins rich pomegranate cream as a topical formulation with anti-aging activity. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2021, 32, 983–990.