Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

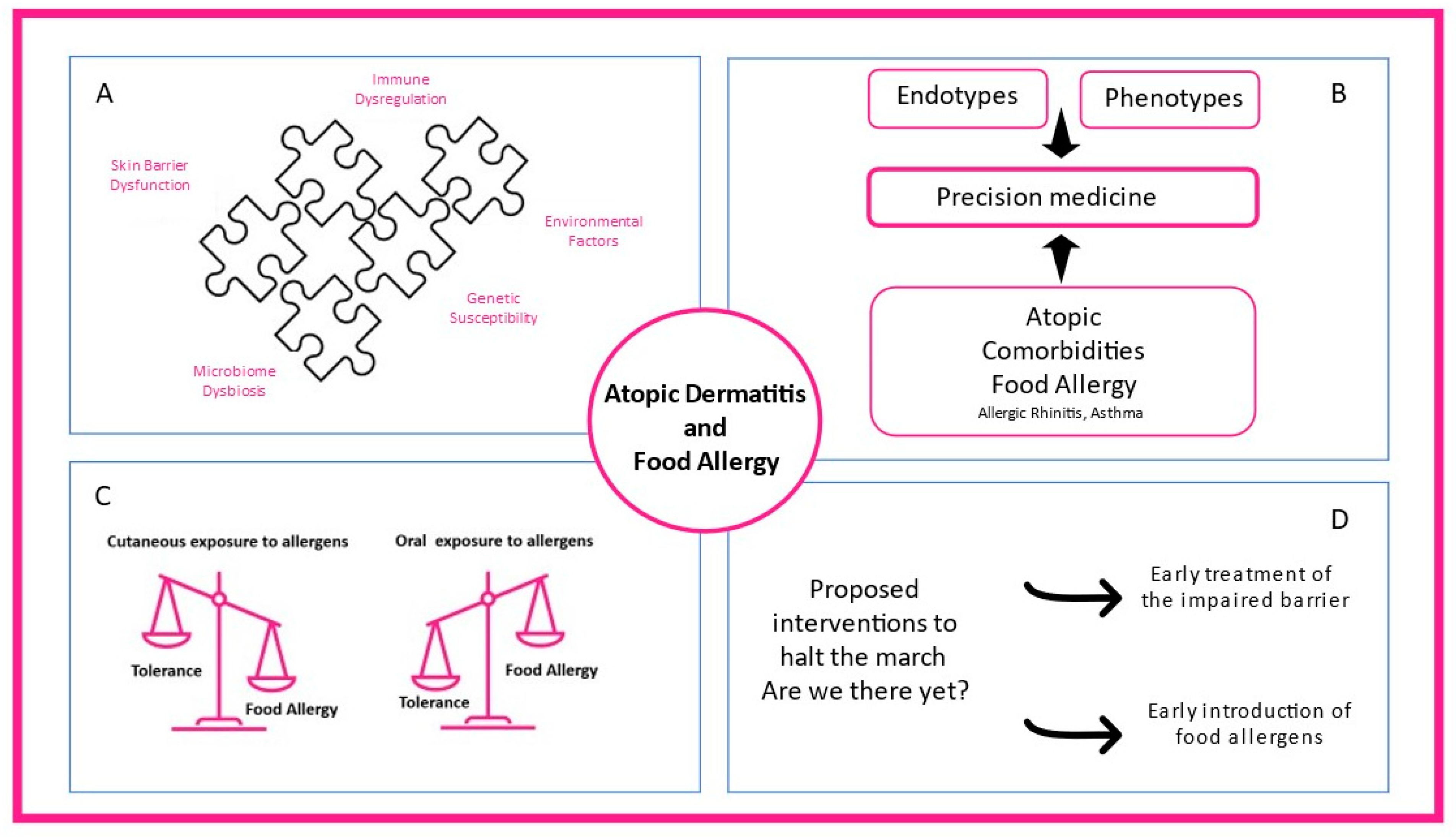

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder characterized by intense pruritus, eczematous lesions, and relapsing course. It presents with great clinical heterogeneity, while underlying pathogenetic mechanisms involve a complex interplay between a dysfunctional skin barrier, immune dysregulation, microbiome dysbiosis, genetic and environmental factors. All these interactions are shaping the landscape of AD endotypes and phenotypes. In the “era of allergy epidemic”, the role of food allergy (FA) in the prevention and management of AD is a recently explored area.

- atopic dermatitis

- food allergy

- food sensitization

1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder affecting more than 230 million people worldwide [1][2]. With an increasing global prevalence, up to 20% of children and 10% of adults in high-income countries suffer from AD [3][4][5], while AD’s morbidity burden designates the disease as the skin disorder with the highest impact on quality of life in terms of disability-adjusted years [6].

AD presents with great heterogeneity in terms of severity, clinical features, and course, with a complex underlying pathophysiology [5], which involves an interplay between the dysfunctional skin barrier, immune dysregulation—starting with a core T helper 2 (TH2) response accompanied by IgE sensitization to environmental allergens and progressing with a widening of the adaptive immunity with TH1, TH17, and TH22 responses—and skin microbiome dysbiosis [7][8]. In addition, genetic susceptibility, along with filaggrin gene’s mutations being the central but not the only recognized genetic disorder, and environmental factors such as ultraviolet radiation, air pollution, water hardness, household hygiene, and climate change contribute to the multidimensional model of atopic dermatitis [9].

As allergic diseases have reached epidemic proportions, with the first epidemic wave of respiratory allergy increasing about 50 years ago, we are now riding a second epidemic wave of “food allergy” [10][11]. In respect to the TH2 endotype, atopic dermatitis has been proposed as the first “step” in a long although debatable pathway known as the “atopic march”, with food allergy, allergic rhinitis, and asthma presenting either concomitantly or at a later stage [12].

Food allergy (FA) is defined as a food hypersensitivity reaction mediated by immunologic mechanisms, while the term IgE-mediated food allergy is used when the role of IgE is underlined [13]. Food sensitization refers to the production of food-allergen-specific IgE but is not synonymous with food allergy, as individuals can produce specific IgEs to foods without presenting symptoms upon exposure. Hence, sensitization is prerequisite but not synonymous with food allergy [14]. Food allergen sensitization can be identified by skin prick testing or in vitro immunoassays for specific IgE to whole-allergens extracts or allergens components (pure allergen proteins) [15][16]. Not only IgE-mediated food allergy but also other endotypes of food allergy (either non-IgE-mediated or mixed) have been implicated either in the exacerbations or in the morbidity of AD complexing even more the landscape of atopic dermatitis–food allergy interaction [17][18] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The complex interplay between atopic dermatitis and food allergy. (A) Skin barrier dysfunction, microbiome dysbiosis, immune dysregulation, environmental factors, and genetic susceptibility contribute to atopic dermatitis heterogeneity. (B) Different endotypes, phenotypes, and atopic comorbidities present in clinical practice shaping precision medicine interventions. (C) While oral exposure to food allergens through the gastrointestinal tract promotes food tolerance, cutaneous allergen exposure can lead to food allergy. (D) Early treatment of the impaired skin barrier and early introduction of food-specific food allergens in high-risk infants are proposed mechanisms to prevent atopic dermatitis and food allergy.

2. Association between Food Sensitization and Food Allergy with Atopic Dermatitis

2.1. Transepidermal Water Loss and Skin Barrier Impairment

A close relationship between atopic dermatitis, food sensitization, and food allergy, especially in childhood, is well-established. Epidermal barrier dysfunction and transepidermal water loss (TEWL) constitute a cornerstone in atopic dermatitis pathophysiology and precedes both the occurrence of atopic dermatitis and food allergy [19][20][21]. Kelleher et al. found that increased TEWL at two days after birth was associated with increased risk of development of AD at one year of age [20]. A constantly growing body of evidence supports that food allergy follows atopic dermatitis diagnosis and leads to the reasonable conclusion that AD is involved in the causal pathway towards food allergy [19][22][23]. Although less commonly, food allergy might precede AD onset in a small number of children [24]. In the Isle of Wight cohort, filaggrin loss-of-function mutations were associated with food sensitization in the early years and food allergy later in childhood, suggesting that skin barrier function per se is important in the development and persistence of food allergy [25].

2.2. Food Sensitization and Food Allergy among Patients with AD

Numerous studies support that more severe phenotypes of AD are associated with more frequent diagnosis of food allergy, ranging between 33% to 39%, with occasional studies reporting higher rates up to 80% [26][27][28][29], while food allergy prevalence in the general population is estimated about 0.1–6% [30]. Hence, atopic dermatitis is proposed as a major risk factor for food sensitization and IgE-mediated food allergy [22][31]. Population-based studies have shown that the likelihood of food sensitization is up to six times higher at 3 months of age in patients with AD compared to healthy controls [22]. When including patients with established AD, the prevalence of food sensitization is up to 66%, while proven food allergy by oral food challenges is up to 81% [22]. The Danish Allergy Research cohort (DARC) showed that up to 53% of children with AD, aged 6 months to 6 years, were sensitized to food allergens, while food allergy was confirmed in 15% of them [19]. In the Health Nut study, a large population-based Australian study (n = 4453), infants with AD were 6 times more likely to have egg allergy (95% CI 4.6, 7.4) and 11 times more likely to have peanut allergy (95% CI 6.6, 18.6) by 12 months than infants without AD at 12 months of age [32]. Although previous studies suggested that the presence of AD, particularly in its more severe form, is associated with a prolonged course of milk and egg allergy [33][34], recent data were not confirmatory [35]. Such discrepancies might be attributed to different study designs and populations with different disease severity.

2.3. Conclusions

Although AD is proposed as a major risk factor for food sensitization and food allergy, its occurrence depends on both severity and chronicity of AD. Rates of food sensitization are high in patients with AD, but frequency of IgE-mediated food allergy confirmed by oral food challenges varies, with more severe AD linked more frequently with food allergy.

3. Patterns of Clinical Reactivity to Foods in Children with AD

There are three patterns of clinical reactivity to foods in children with AD: (a) immediate-type reactions (IgE-mediated within the first 2 h of consumption), (b) delayed exacerbation of AD (non-IgE-mediated), and (c) mixed reactions with a combination of IgE- and non-IgE-mediated clinical features.

3.1. Immediate-Type Reactions (IgE-Mediated)

Immediate-type reactions manifest with either cutaneous symptoms (urticaria, angioedema, flushing) or, in the context of anaphylactic reactions, also including symptoms from the respiratory tract and/or gastrointestinal and/or cardiovascular symptoms (tachycardia, arrhythmias, hypotension, cardiac arrest) [36]. These reactions usually occur within the first 2 h of consumption, ranging from mild single-organ reactions to severe, life-threatening anaphylaxis [36][37].

3.2. Delayed Exacerbation of AD (Non-IgE-Mediated)

Delayed, non-IgE-mediated reactions usually occur 6–48 h after consumption of the implicated food allergens, in most cases, as atopic dermatitis flare up [38]. The pattern of delayed exacerbation of AD is not clearly defined in adult-onset AD. Manam et al. reported that challenge-proven food allergy in adults with AD is uncommon despite higher rates of food sensitization compared to healthy controls. Half of patients with confirmed delayed food allergy by food challenge reported significant decrease of AD exacerbations after strict elimination diet of the offending foods [36].

3.3. Mixed Reactions

Up to 40% of children experience more complex symptoms combining IgE-mediated symptoms and AD exacerbation [39]. In a study of 64 children with AD who underwent 106 double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges to hen’s egg, milk, wheat, or soy, a mixed reaction was observed in 45%, while 12% had only a delayed reaction [40]. However, in the Danish Allergy Research cohort (DARC) study, 95% of the patients during the double-blind placebo-controlled challenges developed the immediate-type reaction [41]. Conclusively, the frequency and pattern of clinical reactivity varies among patients with AD.

4. Diagnosis and Management of Food Sensitization and Food Allergy in Patients with AD

4.1. Sensitization to Food Allergens in AD Patients

In clinical practice, the identification of IgE sensitization can sometimes complicate the management of AD. Food sensitization and food allergy are not synonymous, and thus, not all sensitized patients will react upon exposure to certain food allergens [26]. Knowing the high asymptomatic food allergen sensitization rates in patients with AD and that AD is predominantly a TH2-cell-mediated disease, with IgE being more a “bystander” than an actual driver in the disease, management of food sensitization and allergy in AD patients can be challenging.

In case of patients with AD and a compatible history of IgE-mediated food allergy, in vivo and/or in vivo allergy diagnostic procedures should be conducted. According to international guidelines, food-specific skin tests or sIgEs should be considered in all children below 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD, especially those unresponsive to topical treatment [42]. In the light of Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study results, new addendums were made in the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) published consensus in regard to peanut allergy: (a) In infants with severe AD and/or egg allergy, measurement of peanut IgE level and/or SPT should be conducted before introduction into the diet; (b) infants with mild-to-moderate AD should not be tested for peanut sensitization, and peanut should be introduced in diet approximately at six months of age; and (c) infants without AD should be free in introduction of peanut and other foods according to the wish of the family [42][43].

4.2. The Role of Skin Prick Tests, Atopy Patch Tests, In Vitro Measurement of Specific IgE, and Measurement of Food Allergens Components in the Diagnosis of Food Allergy

The negative predictive value of SPTs to foods in patients with AD is 90–95%, while the positive predictive value is less than 50%, suggesting that these tests are of high value in excluding food allergy [44][45]. Moreover, atopy patch testing (APT) to food allergens has been studied to evaluate non immediate eczematous exacerbations in children with AD. Although promising, they are not standardized yet and are not suggested in routine diagnosis of food allergy in patients with AD [46][47]. More recently, specific IgE levels and the pattern of reactivity to food components have been proposed to distinguish AD food allergic from tolerant subjects. Seventy-eight children with moderate-to-severe AD were assessed due to a history of clinical reactivity to milk, egg, peanut, wheat, and soy, showing that 91% percent of them were sensitized, while 51% reported allergy to at least one of these five food allergens. The IgE levels corresponding to each of these foods as well as the levels of specific components (Bos d8: milk casein, major allergen in cow’s milk; Gal d1: ovomucoid major allergen in Hen’s egg; and Ara h2: 2S albumin, major peanut allergen) were significantly higher in the moderate-to-severe AD allergic group [48].

4.3. The Role of Elimination and Reintroduction of Certain Foods in Diagnosis of Food Allergy

In case of exacerbation of AD due to a potential food allergen, in the absence of an IgE-mediated reaction, an elimination diet is still recommended by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology recent guidelines [49]. Due to a potential placebo effect, which may accompany the elimination, a reintroduction after a short period of time in which an improvement is observed is suggested in order to confirm the diagnosis, and then, a strict elimination diet could follow as long as skin moisturizing is ensured as the first step of standard of care [39].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11144232

References

- Hay, R.J.; Johns, N.E.; Williams, H.C.; Bolliger, I.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Margolis, D.J.; Marks, R.; Naldi, L.; Weinstock, M.A.; Wulf, S.K.; et al. The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1527–1534.

- Bieber, T. Atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1483–1494.

- Odhiambo, J.A.; Williams, H.C.; Clayton, T.O.; Robertson, C.F.; Asher, M.I. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 1251–1258.e23.

- Silverberg, J.I.; Hanifin, J.M. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: A US population–based study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 1132–1138.

- Langan, S.M.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020, 396, 345–360.

- Laughter, M.; Maymone, M.; Mashayekhi, S.; Arents, B.; Karimkhani, C.; Langan, S.; Dellavalle, R.; Flohr, C. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 184, 304–309.

- Narla, S.; Silverberg, J.I. The Role of Environmental Exposures in Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 74.

- Ständer, S. Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1136–1143.

- Weidinger, S.; Beck, L.A.; Bieber, T.; Kabashima, K.; Irvine, A.D. Atopic dermatitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 1.

- Pawankar, R.; Baena-Cagnani, C.E.; Bousquet, J.; Canonica, G.W.; Cruz, A.A.; Kaliner, M.A.; Lanier, B.Q.; Henley, K. State of world allergy report 2008: Allergy and chronic respiratory diseases. World Allergy Organ J. 2008, 1 (Suppl. 6), S4–S17.

- Prescott, S.; Allen, K.J. Food allergy: Riding the second wave of the allergy epidemic. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2011, 22, 155–160.

- Hill, D.A.; Spergel, J.M. The atopic march: Critical evidence and clinical relevance. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 120, 131–137.

- Johansson, S.G.; Hourihane, J.O.; Bousquet, J.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; Dreborg, S.; Haahtela, T.; Kowalski, M.L.; Mygind, N.; Ring, J.; van Cauwenberge, P.; et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001, 56, 813–824.

- Akdis, C.A.; Agache, I.; Allergy, E.A.; Immunology, C. Global Atlas of Allergy; European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: Florence, Italy, 2014.

- Matricardi, P.M.; Kleine-Tebbe, J.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Valenta, R.; Hilger, C.; Hofmaier, S.; Aalberse, R.C.; Agache, I.; Asero, R.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; et al. EAACI Molecular Allergology User’s Guide. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27 (Suppl. 23), 1–250.

- Sur, L.M.; Armat, I.; Duca, E.; Sur, G.; Lupan, I.; Sur, D.; Samasca, G.; Lazea, C.; Lazar, C. Food Allergy a Constant Concern to the Medical World and Healthcare Providers: Practical Aspects. Life 2021, 11, 1204.

- Meyer, R.; Fox, A.T.; Lozinsky, A.C.; Michaelis, L.J.; Shah, N. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal allergies-Do they have a place in a new model of the Allergic March. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2018, 30, 149–158.

- Anvari, S.; Miller, J.; Yeh, C.Y.; Davis, C.M. IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 57, 244–260.

- Eller, E.; Kjaer, H.F.; Høst, A.; Andersen, K.E.; Bindslev-Jensen, C. Food allergy and food sensitization in early childhood: Results from the DARC cohort. Allergy 2009, 64, 1023–1029.

- Kelleher, M.; Dunn-Galvin, A.; Hourihane, J.O.; Murray, D.; Campbell, L.E.; McLean, W.I.; Irvine, A.D. RETRACTED: Skin barrier dysfunction measured by transepidermal water loss at 2 days and 2 months predates and predicts atopic dermatitis at 1 year. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 930–935.e1.

- Tham, E.H.; Rajakulendran, M.; Lee, B.W.; Van Bever, H.P.S. Epicutaneous sensitization to food allergens in atopic dermatitis: What do we know? Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2020, 31, 7–18.

- Tsakok, T.; Marrs, T.; Mohsin, M.; Baron, S.; du Toit, G.; Till, S.; Flohr, C. Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 1071–1078.

- Rustad, A.M.; Nickles, M.A.; Bilimoria, S.N.; Lio, P.A. The Role of Diet Modification in Atopic Dermatitis: Navigating the Complexity. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 23, 27–36.

- Renz, H.; Allen, K.J.; Sicherer, S.H.; Sampson, H.A.; Lack, G.; Beyer, K.; Oettgen, H.C. Food allergy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 17098.

- Venkataraman, D.; Soto-Ramírez, N.; Kurukulaaratchy, R.J.; Holloway, J.W.; Karmaus, W.; Ewart, S.L.; Arshad, S.H.; Erlewyn-Lajeunesse, M. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with food allergy in childhood and adolescence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 876–882.e4.

- Eigenmann, P.A.; Calza, A.-M. Diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy among Swiss children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2000, 11, 95–100.

- Eigenmann, P.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Borkowski, T.A.; Cohen, B.A.; Sampson, H.A. Prevalence of IgE-Mediated Food Allergy Among Children with Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatrics 1998, 101, e8.

- Burks, A.; James, J.M.; Hiegel, A.; Wilson, G.; Wheeler, J.; Jones, S.M.; Zuerlein, N. Atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity reactions. J. Pediatrics 1998, 132, 132–136.

- Niggemann, B.; Sielaff, B.; Beyer, K.; Binder, C.; Wahn, U. Outcome of double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge tests in 107 children with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1999, 29, 91–96.

- Nwaru, B.I.; Hickstein, L.; Panesar, S.S.; Roberts, G.; Muraro, A.; Sheikh, A.; The EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2014, 69, 992–1007.

- Hill, D.J.; Hosking, C.S.; De Benedictis, F.M.; Oranje, A.P.; Diepgen, T.L.; Bauchau, V.; The EPAAC Study Group. Confirmation of the association between high levels of immunoglobulin E food sensitization and eczema in infancy: An international study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2007, 38, 161–168.

- Martin, P.E.; Eckert, J.K.; Koplin, J.; Lowe, A.; Gurrin, L.; Dharmage, S.; Vuillermin, P.; Tang, M.L.K.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Matheson, M.; et al. Which infants with eczema are at risk of food allergy? Results from a population-based cohort. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2014, 45, 255–264.

- Wood, R.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Vickery, B.P.; Jones, S.M.; Liu, A.H.; Fleischer, D.M.; Henning, A.K.; Mayer, L.; Burks, A.W.; Grishin, A.; et al. The natural history of milk allergy in an observational cohort. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 805–812.e4.

- Kim, J.H. Clinical and Laboratory Predictors of Egg Allergy Resolution in Children. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2019, 11, 446–449.

- Giannetti, A.; Cipriani, F.; Indio, V.; Gallucci, M.; Caffarelli, C.; Ricci, G. Influence of Atopic Dermatitis on Cow’s Milk Allergy in Children. Medicina 2019, 55, 460.

- Manam, S.; Tsakok, T.; Till, S.; Flohr, C. The association between atopic dermatitis and food allergy in adults. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 14, 423–429.

- Muraro, A.; Lemanske, R.F., Jr.; Castells, M.; Torres, M.J.; Khan, D.; Simon, H.-U.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Burks, W.; Poulsen, L.K.; Sampson, H.A.; et al. Precision medicine in allergic disease-food allergy, drug allergy, and anaphylaxis-PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Allergy 2017, 72, 1006–1021.

- Robison, R.; Singh, A.M. Controversies in Allergy: Food Testing and Dietary Avoidance in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 7, 35–39.

- Bergmann, M.M.; Caubet, J.-C.; Boguniewicz, M.; Eigenmann, P. Evaluation of Food Allergy in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2013, 1, 22–28.

- Breuer, K.; Heratizadeh, A.; Wulf, A.; Baumann, U.; Constien, A.; Tetau, D.; Kapp, A.; Werfel, T. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2004, 34, 817–824.

- Werfel, T.; Breuer, K. Role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 4, 379–385.

- Boyce, J.A.; Assa’Ad, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; Arshad, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Food Allergy in the United States: Summary of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel Report. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 175–192.

- Togias, A.; Cooper, S.F.; Acebal, M.L.; Assa’ad, A.; Baker, J.R., Jr.; Beck, L.A.; Block, J.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Chan, E.S.; Eichenfield, L.F.; et al. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: Report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017, 118, 166–173.e7.

- Boyce, J.A.; Assa’ad, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; Arshad, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126 (Suppl. 6), S1–S58.

- Sampson, H.A. The evaluation and management of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Clin. Dermatol. 2003, 21, 183–192.

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Li, Z.-Y. The diagnostic value of APT for food allergy in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 451–461.

- Walter, A.; Seegräber, M.; Wollenberg, A. Food-Related Contact Dermatitis, Contact Urticaria, and Atopy Patch Test with Food. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 56, 19–31.

- Frischmeyer-Guerrerio, P.A.; Rasooly, M.; Gu, W.; Levin, S.; Jhamnani, R.D.; Milner, J.D.; Stone, K.; Guerrerio, A.L.; Jones, J.; Borres, M.P.; et al. IgE testing can predict food allergy status in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 393–400.e2.

- Wollenberg, A.; Christen-Zäch, S.; Taieb, A.; Paul, C.; Thyssen, J.; De Bruin-Weller, M.; Vestergaard, C.; Seneschal, J.; Werfel, T.; Cork, M.; et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 2717–2744.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!