Low geometric accuracy is one of the main limitations in double-sided incremental forming (DSIF) with a rough surface finish, long forming time, and excessive sheet thinning. The lost contact between the support tool and the sheet is considered the main reason for the geometric error. Toolpath compensations strategies improve geometric precision without adding extra tooling to the setup. It relies on formulas, simulation, and algorithm-based studies to enhance the part accuracy. Toolpath adaptation improves the part accuracy by adding additional equipment such as pneumatically or spring-loaded support tools or changing the conventional toolpath sequence such as accumulative-DSIF (ADSIF) and its variants. It also includes forming multi-region parts with various arrangements. Toolpath adaptation mostly requires experimental trial-and-error experiments to adjust parameters to obtain the desired shape with precision. Material redistribution strategies are effective for high-wall-angle parts.

- incremental sheet forming

- double-sided incremental forming

- single point incremental forming

- geometric precision

1. Introduction

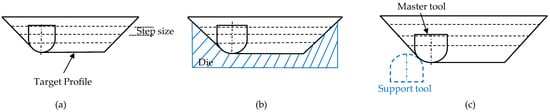

2. Process Mechanism of DSIF

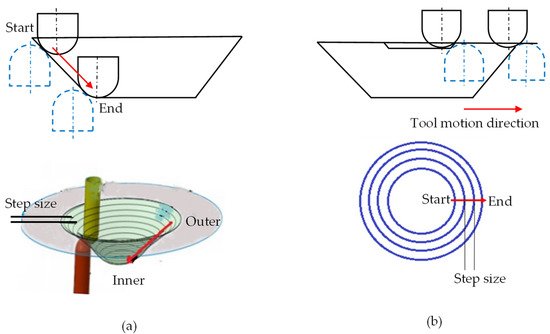

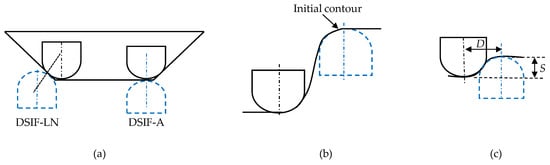

2.1. Toolpath Generation for DSIF Process

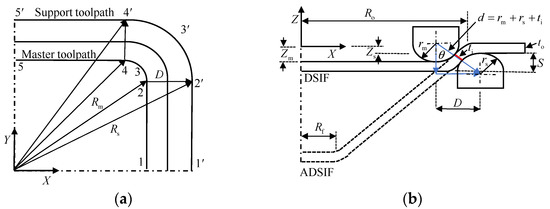

Both for DSIF and ADSIF, the master tool coordinates (Xm,Ym and Zm) are obtained from the CAD/CAM software. The position of the support tool in DSIF and ADSIF was defined via two parameters D and S (Figure 3) by utilizing Equations (1) and (2).

where D is the distance between the axis of the two tools in the XY plane; S is the vertical distance between the bottom of the sheet and the tip of the support tool in the XZ plane; Zm and Zs are the master and support tool position in the XZ plane; Rm and Rs is the master and support tool position in the XY plane. In DSIF, parameters D and S are determined by utilizing the sine law and the normal tool configuration. From Figure 3b, it is evident that D=d⋅sinθ, and S=rm+rs−d⋅cosθ+to, where rm and rs are the master and support tool radius, θ is the local wall angle, and to is the original sheet thickness. The D and S should change continuously as part height increases due to the dependence on the sheet thickness at the contact point (ti) (Figure 3b). Due to sine law limitations, they are mostly held constant after the initial setup at the first contour.

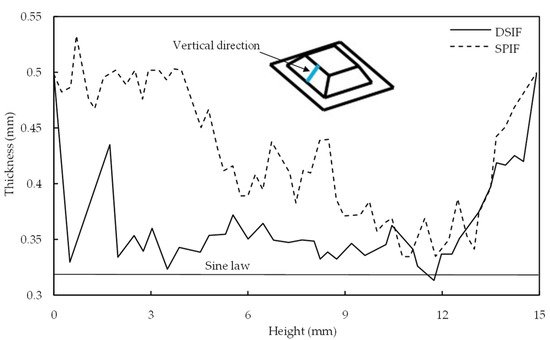

2.2. The Role of Thickness Variations in DSIF Toolpath

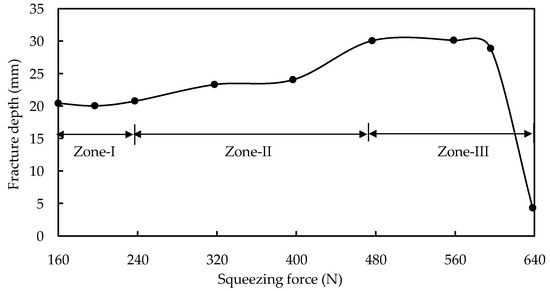

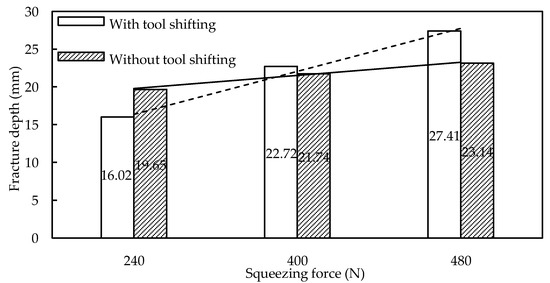

In ISF, the final sheet thickness is usually calculated by sine law, (tf=to⋅sin(90−θ)) where tf: the final sheet thickness after deformation, to: the original sheet thickness, and θ: local wall angle. The local wall angle can be used to find the thickness at any point in the component of complex geometry. The ti (instant sheet thickness) in Figure 3b is not necessarily the sheet thickness predicted by sine law. This difference in ti from the sheet thickness indicated by sine law at different forming heights affects the support tool–sheet contacts. It is due to differences in calculated and actual D and S values. Malhotra et al. [26] initially reported this shortcoming in the sine law while forming the 65° cone. Sine law was used to regulate the gap between the tools. After a certain forming height, the support tool disengaged from the sheet. The process degenerated to SPIF, resulting in early fracture. Squeezing was utilized to improve the support tool–sheet contact; however, it did not ensure accuracy.

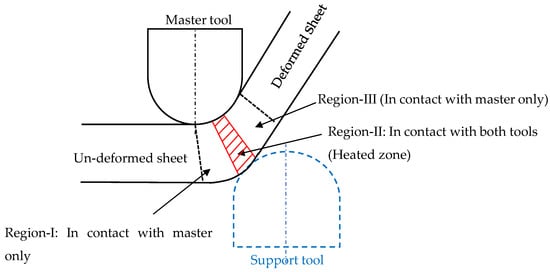

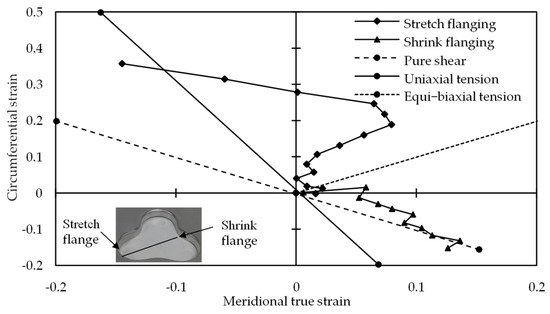

2.3. Deformation and Fracture Mechanism in DSIF

3. Accuracy Improvement in DSIF Process

|

Method |

Part Type |

Error (mm) |

Part Size (mm) (O × H × θ) |

Thick (mm) |

Material |

Cause-and-Effect |

Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

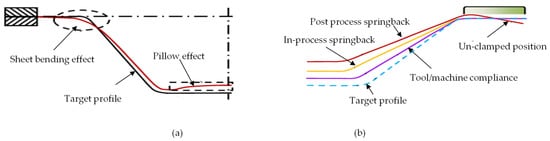

Springback and machine compliances |

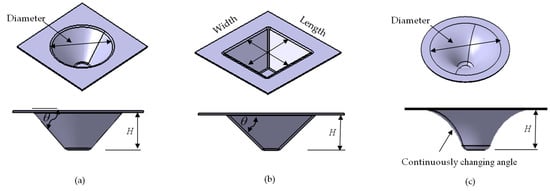

cone |

±0.25 |

100 × 40 × 53° |

0.8 |

AA99.5 |

Springback, sine law-undersize, compliance- oversize |

Meier et al. (2009) |

|

Squeezing (1.0,0.9,0.85) |

cone |

improved |

130 × 36 × 65° |

1.5 |

AA5182 |

Sine law-support tool lost contact |

Malhotra et al. (2011) |

|

Tool gap correction |

shamrock |

NR |

110 × 31.2 × 65° |

1.0 |

AA5754 |

Modified sine law-specific to shamrock |

Moser et al. (2016) |

|

Support tool force control |

cone |

1.0 |

45 × 16 × 40° |

0.5 |

AA2024-T3 |

Complicated- Implementation issue |

Ren et al. (2018) |

|

funnel |

NR |

45 × 22 × 65° |

1.0 |

AA5754-O |

|||

|

In-situ springback |

cone |

0.8 |

70 × 22 × 45° |

0.5 |

AA2024-T3 |

Simulation based-time consuming |

Ren et al. (2019) |

|

pyramid |

0.2 |

80 × 22 × 45° |

1.0 |

AA5754-O |

|||

|

Tool and sheet deflection (small part) |

cone |

0.40 |

78.6 × 20 × 60° |

0.88 |

AA5052-O |

Empirical formula-limited to small parts |

Lingam et al. (2015, 2016) |

|

funnel |

0.46 |

80 × 22.5 × 60° |

|||||

|

Tool and sheet deflection (large part) |

Varying wall component |

1.25 |

260 × 72 × 60° |

0.8 |

AA8011 |

No machine compliance- support tool lost contact |

Praveen et al. (2020) |

|

Elliptical free-form |

1.52 |

640 × 110 × 55° |

|||||

|

Machine, tool, and sheet deflection (large part) |

Varying wall component |

0.62 |

260 × 72 × 60° |

Empirical formula: trialed for AA8011 only with a thin sheet |

Konka et al. (2020) |

||

|

Elliptical free-form |

0.93 |

640 × 110× 55° |

|||||

|

Incremental springback accommodation (D-DSIF) |

Pyramid |

0.33 0.57 |

45 × 15 × 40° 100 × 30 × 45° |

1.0 |

AA7075 DC-04 |

Implementations of the second stage should be based on the formula |

S. Ullah et al. (2021) |

|

Method |

Part Type |

Error (mm) |

Part Size (mm) (O × H × θ) |

Thick (mm) |

Material |

Cause and Effect |

Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DSIF-L DSIF-P DSIF-L DSIF-P |

Free-form |

1.0 |

NR |

NR |

Al Mn 99.8 |

Trial based and sine law-time consuming |

Meier et al. (2011) |

|

2.5 |

|||||||

|

Skull |

<5.0 |

<(120 × 25) |

0.5 |

Grade-1 Titanium |

Insufficient support-increase in error |

Bin Lu et al. (2015 |

|

|

5.0 |

|||||||

|

ADSIF |

Cone |

0.49 |

45 × 14 × 40° |

0.5 |

AA2024-T3 |

Low step size, trial based-time consuming |

Malhotra et al. (2012) |

|

45 × 17 × 50° |

|||||||

|

MDSIF (ASIF+DSIF) |

Pyramid with pocket |

<0.49 |

45 × 15 × varied |

0.5 |

AA2024-T3 |

Based on ADSIF-time consuming |

Zhang et al. (2015) |

|

Reverse bending |

Ellipsoidal |

±0.25 |

Major:112 × 21 × 41.1° Minor:102 × 21 × 44.8° |

1.0 |

AA7075 |

Over bending-precision degradation |

Wang et al. (2018) |

|

Squeezing |

0.4 |

Ineffective-springback reduction |

|||||

|

Automatic feature recognition |

Conical profile with an inclined hump |

0.3 |

80 × 17 × NR |

0.88 |

AA5052 |

Lingam and Ndip-Agbor strategy recommended the sequence in the opposite direction |

Lingam et al. (2017) |

|

pyramid with an inclined base and a protrusion |

0.25 |

80 × 17 × 45° |

|||||

|

Multiple features with Z-based slicing |

Freeform |

1.5 |

<(80 × 18) |

1.0 |

AA5754-O |

Ndip-Agbor et al. (2018) |

|

|

Tool-path adaptation based on STL model |

Bidirectional protruding feature |

3.2 |

<(200 × 25) |

0.6 |

AA1060 |

Springback: precision degradation |

Zhu et al. (2019b) |

|

Method |

Part Type |

Error (mm) |

Part Size (O × H × θ) (O and H in mm) |

Thickness (mm) |

Material |

Researchers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Direct resistance heating |

Cone |

1.0 |

NR |

0.8 |

DX54D |

Meier and Magnus (2013) |

|

High-density pulse |

Pyramid |

NR |

NR × 25 × 45° |

NR |

Titanium |

Asghar and Reddy (2013) |

|

HE-DSIF |

Cone |

1.0 |

80 × 25 × 45° |

1.41 |

AZ3B1 |

Xu et al. (2016) |

|

E-DSIF |

2.2 |

|||||

|

E-SPIF |

>3.0 |

|||||

|

E-MDSIF |

Free-form |

1.98 |

Figure 19 |

0.5 |

Ti6Al4V |

Valoppi et al. (2016) |

|

E-ADSIF |

8.0 |

|||||

|

Without current |

15.42 |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/met12010103