Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Leaf-cutting ants are eusocial insects, as they show a highly developed social structure, manifesting ecological relationships. Their complex structure is characterized by an organized social behavior, the cultivation of a fungus garden and high levels of hygiene, which hinders the management of leaf-cutting ants compared to other insects. Leaf-cutting ants cause damage in agricultural and silviculture areas, mainly in monocultures.

- pesticide

- antifungal activity

- chemical control

- biological control

- natural products

- synthetic compound

1. Introduction

Large-scale insect populations that damage crops are considered pests and include Sitophilus zeamais Motschulsky (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), the maize weevil, which impairs the storage of corn grains (Zea mays, Poales: Poaceae) with a large occurrence in Brazil [1]; Spodoptera frugiperda Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), the fall armyworm, which causes damage to soybean (Glycine max, Fabales: Fabaceae), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, Poales: Poaceae), sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum, Poales: Poaceae) and so on. and is native to the tropical regions of North and South America [2][3]; Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), the diamondback moth, the main pest in the cultivation of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Brassicales: Brassicaceae) and cauliflower (B. oleracea var. botrytis, Brassicales: Brassicaceae), it has an extensive distribution in tropical and subtropical areas [4][5]; and ants of genera Atta and Acromyrmex (Formicidae: Attini), which attack a great diversity of plants [6].

The fungus Leucoagaricus gongylophorus (Möller) Singer (Agaricales, Agaricaceae) is the symbiotic partner of several species of Attine ants, whose development on leaves cuts inside the nests to form the fungus gardens. The fungus produces enzymes that degrade leaf polysaccharides into nutrients assimilable by ants. Among these nutrients, glucose produced from plant material in the fungus garden appears to be the main source of food for ants along with proteins and amino acids [7]. Leaf-cutting ants from the Myrmicinae family, tribe Attini (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), are native to the Neotropics and belong to two genera: Atta and Acromyrmex [6][8][9].

The use of chemical pesticides for insect pest control, often applied without legal supervision, has led to environmental issues such as the death of beneficial insects, parasitoids, and predators, and pesticide residues in the soil [10]. It was to discover active compounds from natural sources have contributed to the identification of new agrochemical substances [11].

The characterization of plant extracts and natural compounds that have shown direct lethal activity on leaf-cutting ants is well explored, such as the extracts of Asclepias curassavica (Asclepidaceae) [12] and Virola sebifera (Myristicaceae) [13] and isolated compounds such as alkaloids, limonoids [14], sesquiterpenes [15], and flavonoids [16].

Another approach to control leaf-cutting ants would be the application of extracts or compounds acting on the symbiotic fungus L. gongylophorus, an important microorganism in the management and survival of the nest [14][16][17]. Based on a mutualistic relationship with the leaf-cutting ants, the control of this insect can be carried out at the insecticide or fungicide level, either individually or by combining these two strategies to provide an efficient integrated control [18][19]. Baits with insecticides such as chlorpyrifos, deltamethrin, fipronil, and permethrin, but mainly sulfluramid, based on citrus pulp on which the mutualistic fungus feed, have been the main tool for the control of leaf-cutting ants [20][21]. Sulfluramid is one of the most successful active ingredients for the control of leaf-cutting ants because it is chemically and physically stable and has a delayed toxic action [22][23]. In addition, these eusocial insects do not detect it as a hazardous material, that is, sulfluramid is not repellent and is distributed by the ants themselves in a large number of fungus garden compartments inside the nest contaminating as many ants as possible when they feed [24]. However, sulfluramid was listed as a persistent organic pollutant at the Stockholm Convention in 2015 [25][26]. Therefore, it is necessary to find alternatives to sulfluramid for the control of leaf-cutting ants, including methods or active compounds that act on the mutualistic fungus; however, this control approach has been little explored and there are no baits with fungicide that act directly on L. gongylophorus.

Products used in pest control, in addition to being effective, should be safe for the environment and non-target organisms. Thus, the use of alternative methods involving natural substances or based on them (synthetic compounds), as well as the use of other microbes with fungicidal action, is convenient. The reports examples of chemical and biological controls that have shown potential against the symbiotic fungus L. gongylophorus and that could be better explored.

1.1. Damage Caused by Leaf-Cutting Ants

Leaf-cutting ants are eusocial insects, as they show a highly developed social structure, manifesting ecological relationships [27]. Their complex structure is characterized by an organized social behavior, the cultivation of a fungus garden and high levels of hygiene, which hinders the management of leaf-cutting ants compared to other insects [23].

Leaf-cutting ants cause damage in agricultural and silviculture areas, mainly in monocultures. Plants aged 1 to 3 years are the main targets of these ants and are defoliated, causing irreversible damage, since the seedlings are new and fragile [28], causing significant yield losses [29][30]. Defoliation affects the growth of plants because the increase in diameter is dependent on the current level of photosynthesis, which is reduced by the loss of leaves [31]. In addition, a lesser effect is observed on height loss, since growth is related to the plant reserves.

One carried out in Pinus taeda plantations in Argentina concluded that there was a reduction of 17.3% in the growth in the neck diameter of plants aged up to 12 months attacked by leaf-cutting ants belonging to the genus Acromyrmex [32]. In another one carried out in 10-year-old Pinus caribaea trees in Venezuela, attacks by Atta laevigata reduced wood production up to 50% ha−1 [33]. In this same way, a level of economic damage between 13.4 and 39.2 m2 ha−1 was observed in a eucalyptus site in areas of the Atlantic Forest after infestation by leaf-cutting ants (Atta sp.) [34]. Similar values (7.02 to 34.86 m2 ha−1) were also observed for the same cultivation in Cerrado, another Brazilian biome [26].

Leaf-cutting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of the genera Atta and Acromyrmex are the main pests in Brazil, affecting Pinus and Eucalyptus plantations [35]. These leaf-cutting ants removed 20–30% of the total leaf area of fruit, cocoa, and crops of other plants documented in Trinidad and in Guadalupe (Central America) [36], resulting in an annual loss higher than USD 250,000. Measurements of four Eucalyptus stands showed a total of 2327 nests of leaf-cutting ants with 4742.27 m2 of surface area (loose soil). The number of leaf-cutting ant nests and their area per hectare were 64.52 and 238.90 m2, respectively [37]. Between 1991 and 1996, the average total cost of combatting attacks by leaf-cutting ants in a 6-month-old eucalyptus forest was USD 12.60 per ha−1 in Brazil [38]. In 2011, the updated values for the control of this pest in Brazil were around USD 1.23 per ha−1, considering a market value of eucalyptus wood of USD 18.00 per m−3 [34][37].

Due to the vast regions affected by leaf-cutting ants, avoiding the damage they cause requires high control costs. Economic losses from leaf-cutting ants, either through reduced yields or through expenses for their control, run into the billions of dollars worldwide, reaching more than 30% of the total costs spent on forest management [39]. Fenitrothion, fipronil, or sulfluramid are examples of the most common synthetic active ingredients used to combat leaf-cutting ants, but they are banned in some countries [36]. Although other methods have been evaluated, these chemicals are the only ones to show really satisfactory effects for controlling this pest [9][23][40]. Thus, a better understanding of how the structure of leaf-cutting ant nests works as well as the division of tasks between their mutualistic organisms are key points in the search for new targets to combat this pest.

1.2. Biological Relationship between Leaf-Cutting Ants and Their Mutualistic Fungus

The description of a complex microbial environment of leaf-cutting ants, their obligatory association with the basidiomycete species L. gongylophorus, and the maintenance of the fungus gardens is well reported [41][42][43]. Through the symbiotic relationship between leaf-cutting ants and the fungus L. gongylophorus, the microorganism offers enzymes that break down plant tissues and detoxify some compounds that may have insecticidal characteristics so that the ant has access to plant material that would not be possible without the work of the fungus [44][45].

Glucose produced from plant material in the fungus garden seems to be the main food source for leaf-cutting ants of the genus Atta [46]. L. gongylophorus produces glucose from plant material through, for example, starch hydrolysis by fungal extracellular α-amylase and maltase. This is an ongoing process inside the ants’ nest by which this symbiotic fungus contributes to the ant nutrition with starch [47]. Starch and xylan are consumed by L. gongylophorus faster compared to cellulose. This fungus can efficiently hydrolyze these polysaccharides and assimilate xylose, maltose, and glucose in order to make these nutrients available to the ants [48].

L. gongylophorus produces swollen structures at the tip of the hypha called gongylidia. A grouping of gongylidia forms staphylae, which provide food for the ants and their larvae [49]. The process takes place by the harvesting of a staphylum or bundle of hyphae by the workers and placing it directly in the larval mouthparts, or the workers handle the staphylae or hyphae until they reach the ideal consistency and then deposit them in the larval mouthparts [50]. Staphylae or hyphae are the main sources of nutrients for immature ants. Larvae need a high protein intake for growth, which can only be provided by L. gongylophorus [51]; when they are fed an artificial staphylae-based diet they gain more weight [52]. Larvae of Atta cephalotes obtain 100% of their feed from staphylae, but workers obtain only 4.8% of their respiratory energy needs from this source, while the rest of their needs are presumably supplied by the sap of the plant [52]. In other words, the fungus is not the greatest source of food for workers, since they take up nutrients while harvesting plant material [53].

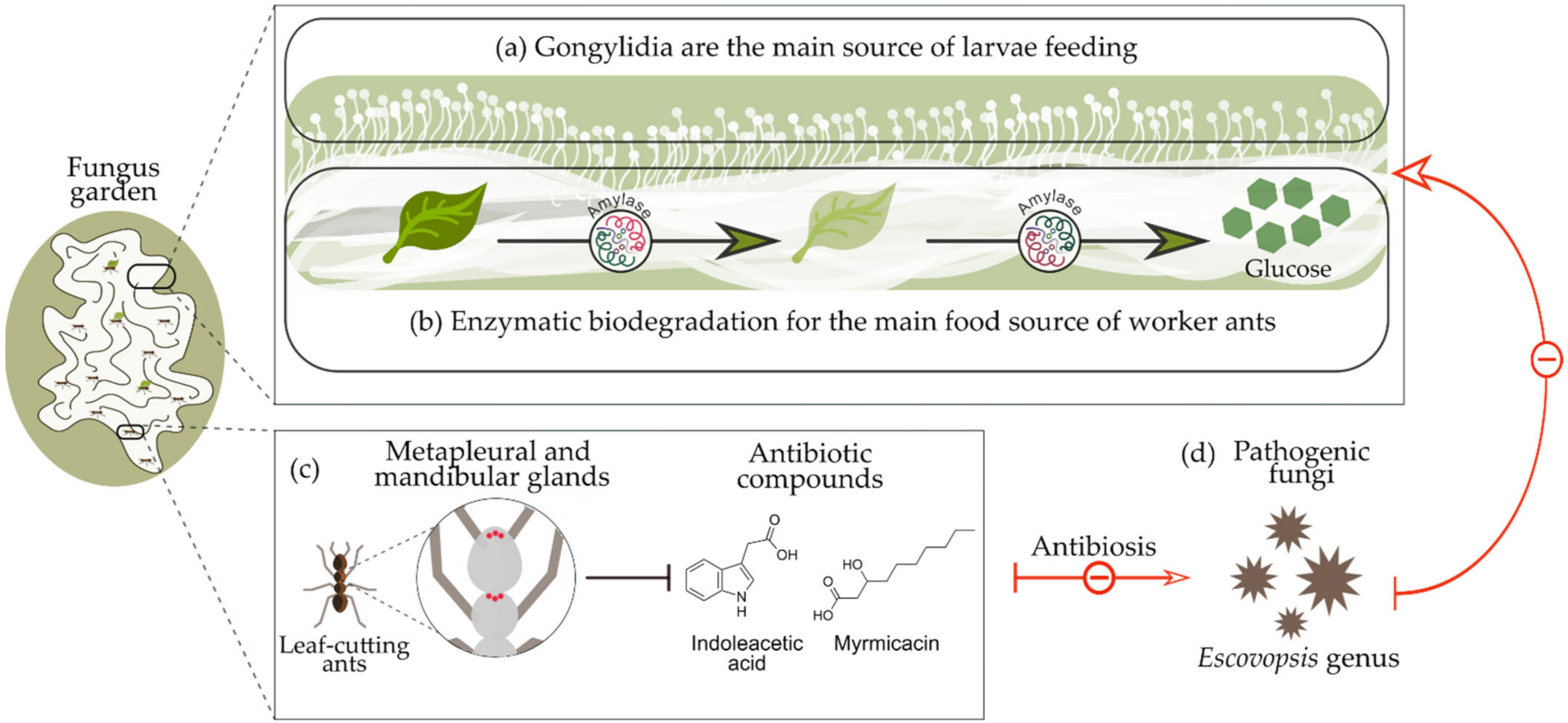

Workers do not digest many of the fungal enzymes when they consume gongylidia, but they deposit these enzymes in the upper parts of the fungus garden through the fecal fluid of the chewed plant material, thus providing adequate environmental conditions to nourish their fungal partners [54][55]. This allows the cultivation by ants to surpass other microbes present in the garden. For example, ants are generally known to eliminate foreign microbes within their gardens by producing antibiotics in their metapleural and mandibular glands [56][57], such as 3-hydroxydecanoic (myrmicacin) and indoleacetic acid, produced from the genera Atta and Acromyrmex [58]. A schematic summary of the relationship between leaf-cutting ants and their symbiotic fungus L. gongylophorus is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Symbiotic relationship between leaf-cutting ants and Leucoagaricus gongylophorus symbiotic fungus: (a) Gongylidia produced in the fungus garden are the main source of food for the ant larvae; (b) fungus enzymes such as amylase are responsible for the biodegradation of organic material into glucose, the main food source for the worker ants; (c) leaf-cutting ants produce antibiotic compounds that protect the fungus garden against harmful agents; (d) pathogenic microorganisms such Escovopsis fungal genera.

2. Fungal Control

Different compounds have been known as novel alternatives for the control of leaf-cutting ants, since commercially available products, generally synthetics, have disadvantages such as side effects towards non-target organisms and environmental contamination. Searches directed at Brazilian Forest Stewardship Council-certified forestry companies showed that chemical control (82%) is the most important method for pest management, followed by biological control (71.4%), tree resistance (54%), cultural control (37.5%), and mechanical control (34.5%) [59]. Based on this, a comparison between the main chemical and biological controls with effects on the fungus garden was carried out in order to propose new agents to replace the commercially synthetic available products.

“Leaf-cutting ant *”, “fungus growing ant *”, and “leaf cutter ant *” were used as query keywords in the PubMed and Web of Science databases. The use of the symbol “*” in the databases is not to limit the search only to the characters of keywords, but to search for words with similar spellings. Those published through 31 August 2020 and written in the English, Portuguese, and Spanish languages were selected. The total search found 1929 (1924 in English, 1 in Portuguese, and 4 in Spanish); after a complete reading of the abstracts, only 26 were included. Those related to chemical characterization analysis only were excluded. Extracts and isolated and synthetic compounds as well as microorganisms reported in trials against L. gongylophorus were tabulated and classified according to the type of control. The selected materials were considered active according to the methodology applied in each.

2.1. Chemical Control

2.1.1. Natural Compound

The chemical complexity of natural compounds is an important source in the search for new antifungal agents; however, some naturally occurring structures can be difficult to produce synthetically [60], but they can be used as sources of semi-synthetic compounds [61]. In addition, natural compounds can be less dangerous and persistent, which can lessen the risks compared to conventional products used in crop pest control [62]. These qualities, added to the antimicrobial potential presented by essential oils and plant extracts, reinforce the promise of these products as alternatives for agricultural use. In this sense, several works have already demonstrated the potential of natural compounds as fungicidal agents on the symbiotic microorganism of leaf-cutting ants. Although all the studies reported here were based on in vitro methods, the results are promising and the data can be used for future trials in in vivo systems to confirm the effect on leaf-cutting ant control.

2.1.2. Synthetic Compounds

Although the chemical variety of natural products is extensive, synthetic compounds have advantages related to purity as well as the ease of large-scale production [63]. Various synthetic products showed toxic effects against L. gongylophorus, including fatty acids with 6–12 carbons [61]. Although no differences in activity were observed among them, the inhibition of fungal growth can vary according to the number of carbon atoms: the longer the chain, the greater the biological effect. This observation can be proven from the synthesis of piperonyl compounds, since an increase in the length of the side chain from two to eight carbons reduced the concentration effective against the symbiotic fungus almost 10-fold. However, this relationship is not continuous, as a reduction in antifungal activity was observed for side chains with more than 10 carbons [64].

2.2. Biological Control Using Microorganisms

As previously discussed, leaf-cutting ants live in symbiosis with other microorganisms that assist in their feeding and protection. However, drastic changes in the environment in which they live can affect the balance of the nest, favoring the development of other invading organisms [65]. Among them, the species of the genera Escovopsis [65][66][67] and Trichoderma [65][68][69] can be highlighted as the main threats. Escovopsioides nivea is also effective in reducing fungal mycelium development [66], and lower values of inhibition were demonstrated for Acremonium kiliense [65] and Gliocladium sp. [69] species. However, Syncephalastrum sp. showed a harmful effect on sub-colonies regardless of the occurrence of the disturbance to the ants’ nest, suggesting that it may be susceptible to attack by pathogenic microorganisms even under normal conditions (healthy sub-colonies) [70].

When the nest is under attack by invading microorganisms, there is a reduction in biomass in the fungus garden since they consume the nutritional content of L. gongylophorus [65]. Inhibitory effect on the fungus garden shown by A. kiliense is related to this nutritional competition [65]. The degradation of the symbiotic fungus produces substances that can also be used as a food source for the species of Escovopsis and Trichoderma, indicating a necrotrophic relationship between them [65]. A combination of mechanisms of action can also be found for the same microorganism, such as Gliocladium, which both inhibits development and competes for nutrients [69]. Other mechanisms of action, such as the production of substances with antibiotic potential or that degrade the cell wall, may also be involved in the antifungal control [68].

Different microorganism strains, fungi, or bacteria may have different mechanisms on L. gongylophorus since the genetic homogeneity of this mutualistic fungus restricts its capacity for defense against different organisms [67]. This can be observed in the increase in the percentage of mycelium growth inhibition from 43 to 78% after the attack by Escovopsis strains [65][66][67]. Trichoderma species also showed large divergences (1–75%) in inhibition of the growth of L. gongylophorus [65][68][69].

Although L. gongylophorus is susceptible to other microorganisms, their direct application in the field would not be viable since this effect would probably be lost over time. This is because leaf-cutting ants exhibit highly specialized hygiene behavior that allows the creation of barriers to invasion by other microorganisms as well as being able to eliminate them [65][66][67][70]. However, microorganisms have primary and secondary metabolisms similar to those of plants; therefore, they can be considered a rich source of active substances for chemical control. As examples, the lactones antimycins A1–A4 (N5–N8), obtained from Streptomyces sp. [71], and extracts of E. nivea and Escovopsis [66] suppress the growth of L. gongylophorus.

Conventional biological control methods using the direct application of microorganisms in the environment do not seem to be the ideal way to combat this crop pest due to the hygienic behavior of the leaf-cutting ants. Thus, metabolomics research could be an alternative in the search for novel compounds active against L. gongylophorus. On the other hand, pathogenic fungi have already shown insecticidal action better than that of chemical controls, suggesting that the application of a biological control on leaf-cutting ants may be possible and applicable [72]. Ideally, pathogenic fungi would act faster than the ability of leaf-cutting ants to eliminate them, and that would have an action specific to these insects; so, microorganisms that avoid any environmental imbalance would be preferable for biological control. Little is known about how these organisms interact in the fungus garden, and further are needed into the mechanism of the antifungal action.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/insects13040359

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!