β-cells are insulin-producing cells in the pancreas that maintain euglycemic conditions. Pancreatic β-cell maturity and function are regulated by a variety of transcription factors that enable the adequate expression of the cellular machinery involved in nutrient sensing and commensurate insulin secretion. One of the key factors in this regulation is MAF bZIP transcription factor A (MafA). MafA expression is decreased in type 2 diabetes, contributing to β-cell dysfunction and disease progression. The molecular biology underlying MafA is complex, with numerous transcriptional and post-translational regulatory nodes.

- MafA

- pancreatic beta cells

- beta cell maturity

- transcription factors

- diabetes

1. Introduction

2. MafA Regulates β-Cell Function

3. MafA Target Genes

|

Gene Symbol |

Gene Name |

Gene Function |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cacng4 * |

Voltage-dependent calcium channel gamma-4 subunit |

Enhances L-type Ca2+-mediated Ca2+ entry into β-cell |

[45] |

|

Chrnb4 * |

Cholinergic receptor nicotinic beta 4 |

Subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor |

[46] |

|

Cox6a2 * |

Cytochrome C oxidase subunit 6A2 |

One out of 13 subunits of cytochrome C oxidase complex (Complex IV), the last enzyme in the electron transport chain |

[47] |

|

G6pc2 * |

Glucose-6-phosphate catalytic subunit related protein |

Islet-specific enzyme that hydrolyzes glucose-6-phosphate, limits basal insulin secretion |

[48] |

|

Gck |

Glucokinase |

Phosphorylates glucose to glucose-6-phosphate in pancreatic islets and hepatocytes. Considered the β-cell glucose sensor |

[49] |

|

Glp1r |

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor |

Receptor for Glucagon-like peptide 1 (Glp1), a stimulator of insulin secretion |

[49] |

|

Ins1 * |

Insulin I |

One of two insulin genes in mouse, on chromosome 19 |

[11] |

|

Ins2 * |

Insulin II |

One of two insulin genes in mouse, on chromosome 7 |

[11] |

|

Maob * |

Monoamine oxidase B |

Metabolizes monoamine neurotransmitters, specifically benzylamine, dopamine and phenylethylamine |

[50] |

|

Neurod1 |

Neurogenic differentiation 1 |

Transactivator of genes important for β-cell maturation and function, including insulin |

[49] |

|

Nkx6.1 |

NK6 homeobox1 |

TF involved in β-cell development and regulation of genes involved in mature β-cell function |

|

|

Pcsk1 |

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 |

Proprotein convertase, which processes proinsulin in β-cells |

[49] |

|

Pcx |

Pyruvate carboxylase |

Catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to oxaloacetate |

[49] |

|

Pdx1 * |

Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 |

TF important pancreas development and for mature β-cell function |

|

|

PPP1R1A |

Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory inhibitor subunit 1A |

Regulates cAMP/PKA signaling pathway Promotes Glp1-induced GSIS |

[53] |

|

Prlr |

Prolactin Receptor |

Involved in increasing β-cell mass during pregnancy |

[54] |

|

Slc2a2 * |

Solute Carrier Family 2 Member 2 |

Glucose transporter 2, transmembrane glucose transporter with a high Km for glucose |

|

|

Slc80a8 |

Solute carrier family 30 member 8 |

Zinc transporter on insulin granules in β-cells |

4. Regulation of MafA Transcription

|

Protein Symbol |

Protein Name |

Mafa Transcription Mechanism |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pax6 |

Paired box protein Pax-6 |

Binds R1, R3 and R6 of the Mafa promoter |

[58] |

|

Nkx6.1 |

NK6 homeobox 1 |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[58] |

|

Nkx2.2 |

NK2 homeobox 2 |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[57] |

|

Pdx1 |

Pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 |

Binds R3 and R6 of the Mafa promoter |

|

|

Hnf1a |

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-alpha |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[56] |

|

Foxa2 |

Forkhead box A2 |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[57] |

|

Isl1 |

Insulin gene enhancer protein ISL-1 |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[62] |

|

Neurod1 |

Neurogenic differentiation 1 |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[57] |

|

Pax4 |

Paired box protein Pax-4 |

Negative regulator of Mafa, potentially by interfering other factors from binding R3 of the Mafa promoter |

[60] |

|

Mafb |

Transcription factor MafB |

Binds R3 of the Mafa promoter |

|

|

Onecut1 |

One cut domain, family member 1 |

Prevents Foxa2 from binding to the Mafa promoter |

[61] |

|

Foxo1 |

Forkhead box O1 |

Binds to the forkhead element of the Mafa promoter |

[34] |

|

Thra |

Thyroid hormone receptor alpha |

Binds to Thyroid hormone response element (TRE), which are located from −1927 to −1946 and from +647 to +659 (named Site 2 and Site 3, respectively) |

[64] |

|

CREB |

cAMP responsive element binding protein |

Constitutively binds to the cAMP response element (CRE), spanning from −1342 to −1346, of the Mafa promoter |

[65] |

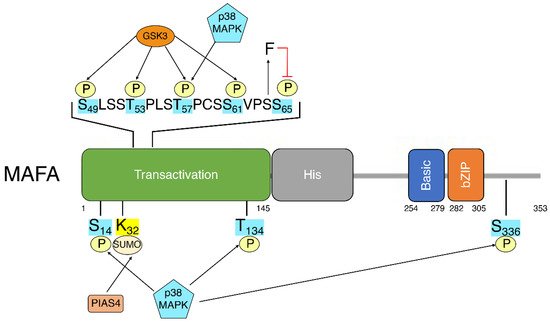

5. MafA Post-Translational Modifications

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom12040535