Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common compression neuropathy in the general population and is frequently encountered among individuals with type 1 and 2 diabetes. The reason(s) why a peripheral nerve trunk in individuals with diabetes is more susceptible to nerve compression is still not completely clarified, but both biochemical and structural changes in the peripheral nerve are probably implicated. In particular, individuals with neuropathy, irrespective of aetiology, have a higher risk of peripheral nerve compression disorders, as reflected among individuals with diabetic neuropathy. Diagnosis of CTS in individuals with diabetes should be carefully evaluated; detailed case history, thorough clinical examination, and electrophysiological examination is recommended. Individuals with diabetes and CTS benefit from surgery to the same extent as otherwise healthy individuals with CTS.

1. Introduction

Nerve compression disorders are common among the general population, and the most frequently encountered lesions are carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and ulnar nerve entrapment at the elbow (UNE)

[1]. Even if both conditions are considered as nerve compression disorders, they have substantially different characteristics, regarding the socioeconomic background of affected individuals as well as the individual nerve’s susceptibility and reaction to trauma; factors that both impact outcome of surgical procedures

[2][3]. The prevalence of CTS is 2.7% (depending on its definition) and the yearly incidences are 428 in women and 182 in men per 100,000 adults in Sweden

[4][5], but figures may differ between both regions and countries

[6][7][8]. In addition, the annual incidences of CTS surgery are higher in Sweden and the United States compared to, e.g., in the United Kingdom

[1][5]. The aetiology behind CTS is multifactorial, and both intrinsic and extrinsic factors; i.e., factors related to both the peripheral nerve and the surroundings of the nerve trunk have to be considered. Frequent causes of CTS are endocrine disorders, like hypothyroidism, pregnancy, menopause, obesity, diabetes, Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS), rheumatoid arthritis, traumatic injuries, such as fractures and dislocations of the distal radius and carpal bones, and repetitive motions of the wrist. However, in the majority of CTS cases, no specific cause can be identified, and the condition is considered as idiopathic. Recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have reported 16 susceptibility loci for CTS

[9], and as the variants in those genes are implicated in both growth (i.e., anthropometric measurements) and enrichment of extracellular matrix architecture, the genetic risks are related to the environment of the carpal tunnel as well as to the vulnerability of the median nerve fibres to compression. CTS is also considered to be a part of the diabetic hand, which includes not only limited joint mobility, Dupuytren’s disease with contracture, and flexor tenosynovitis (i.e., trigger finger)

[10][11], but also ulnar nerve compression at the elbow (UNE)

[12]. Diabetes increases the risk of compression neuro-pathies

[13][14], and a prominent feature may be inherent factors in the peripheral nerve trunk, comparable to HAVS

[15][16][17]. This phenomenon is included in the double crush theory; a nerve already affected by some pathology is more susceptible to compression

[15].

2. Neuropathy in Diabetes

The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy is estimated to be 30–50% in individuals with diabetes

[18][19][20], and it increases with disease duration. Importantly, diabetic neuropathy may be present already at the time of diagnosis

[21][22], where diabetic men are more prone than diabetic women to develop neuropathy

[23]. The most common type of diabetic neuropathy is distal symmetric polyneuropathy, a major cause of diabetic foot complications

[21]. Other neuropathy types in diabetes are autonomic neuropathy and mononeuropathies, including compression neuropathies

[21].

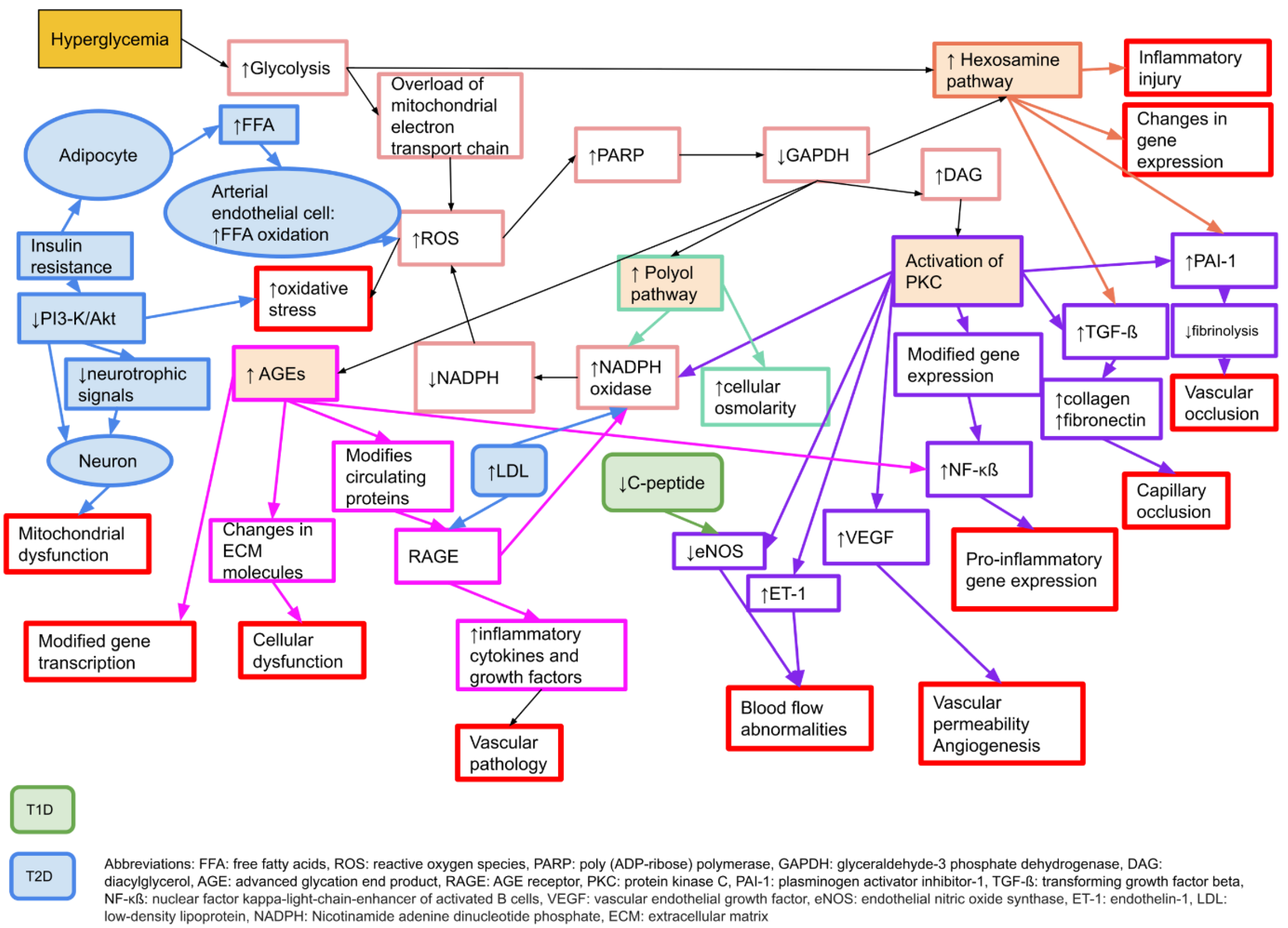

There are several proposed mechanisms behind the development of neuropathy in diabetes. The main causal factor is considered to be hyperglycaemia

[24], which leads to an increased oxidative stress and an increase in free radicals

[25]. Pathophysiologically, there are four key elements behind the hyperglycaemic damage to peripheral nerves; increased activity in the polyol pathway, activation of protein kinase C (PKC), production of advanced glycation end products (AGE), and an increased activity of the hexosamine pathway

[24]. For details, please see

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms behind microvascular complications in diabetes that may affect neurons, Schwann cells, and vascular endothelial cells, causing neuropathy or nerve dysfunction. Adapted from Zimmerman 2018

[26] with permission. T1D: type 1 diabetes, T2D: type 2 diabetes.

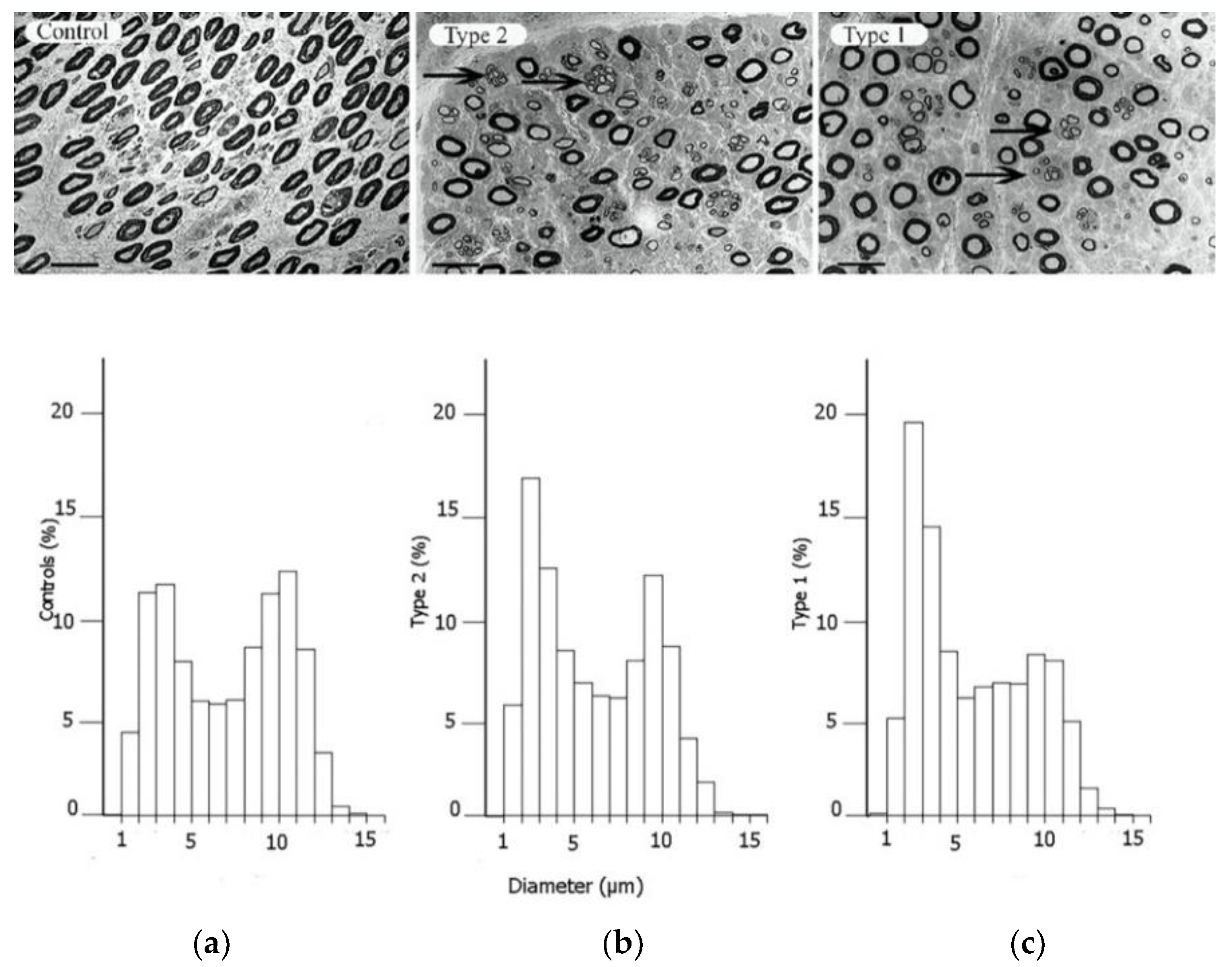

Alterations in axonal transport have also been described in experimental studies of diabetes

[27][28]. These changes result in reduced axon calibre, segmental demyelination, and loss of myelinated nerve fibres

[29] (

Figure 2). Both micro- and macrovascular alterations in diabetes add additional stress on peripheral nerves. However, the mechanisms behind diabetic neuropathy differ between type 1 and type 2 diabetes

[18][30][31]. In type 1 diabetes, intensive glucose control protects against neuropathy development

[30][31], and insulin deficiency might contribute to neuropathy since insulin has a neurotrophic effect

[32]. The loss of C-peptide in type 1 diabetes might also contribute to hypoxia by lowering eNOS

[33]. In contrast, in type 2 diabetes, both hyperlipidaemia and insulin resistance may play a part in the development of neuropathy

[32][34][35][36]. There is also evidence that glucose control may have a modest effect on lowering neuropathy complications in type 2 diabetes

[37][38].

Figure 2. Electron micrographs of the posterior interosseous nerve, with diagram of size distribution of myelinated nerve fibres, from patients with CTS, where the individuals are healthy (

a), have type 2 diabetes (

b) or type 1 diabetes (

c). The arrows in the upper panels indicate regenerative clusters. In the diagram on the lower panels, the size distribution of myelinated nerve fibres is based on the micrographs from the upper panels, indicating a redistribution of nerve fibres. Scale bar = 20 µm. Reproduced by kind permission by Osman et al., Diabetologia 2015

[39].

3. The Increased Susceptibility to Nerve Compression in Diabetes

A peripheral nerve trunk is a delicate structure, where the various components respond to an external trauma in different ways (for a classical review, see Sunderland 1978

[40]). The axons, with their associated Schwann cells, are enclosed by a basement membrane, and the myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibres are assembled in bundles surrounded by a strong connective tissue layer with flattened cells (perineurium), providing both chemical and mechanical protection

[40][41]. The connective tissue component inside the perineurial sheath is called the endoneurium. The bundles of nerve fibres with the perineurium (i.e., fascicles) are embedded in loose connective tissue components—epineurium. The nerve trunk is segmentally provided by small blood vessels that branch into the different connective tissue compartments, where the endoneurial blood vessels, mainly capillaries, are strongly resistant to trauma

[42]. In contrast, the epineurial blood vessels are sensitive to trauma with a risk of formation of epineurial oedema that may later form into fibrosis. The number of nerve fibres with a larger diameter, i.e., the myelinated fibres, are reduced, particularly in type 1 diabetes, with a resulting bimodal distribution of nerve fibres (

Figure 2); i.e., a higher number of unmyelinated nerve fibres

[39]. Myelinated nerve fibres are also more sensitive to nerve compression trauma than un-myelinated nerve fibres

[43].

The intra-axonal communication system consists of a delicate system of anterograde and retrograde transport of various substances, such as structural, metabolic, and growth-related proteins, known as axonal transport, which is of utmost relevance in health and disease

[44]. Axonal transport can not only be disturbed in diabetes with the development of neuropathy, but can be inhibited by applied nerve compression

[27][45]. In experimental studies using diabetic rats, local compression of a nerve causes an increased inhibition of axonally transported proteins compared to in healthy rats

[45]; the concept is conceivable that a nerve is more susceptible to compression when the peripheral nervous system is affected by a generalised disease, such as diabetes

[15]. In this context, one has also to consider all related disturbances in diabetes, such as those occurring in the red blood corpuscles, the extra- and intraneural blood vessels, and in the connective tissue components whether in the nerve trunk or in the surroundings as in the carpal ligament, e.g., with glycosylation of collagen. The glycosylation of collagen leads to an increase in advanced glycation end products (AGE), causing cross-linking of collagen fibres in the transverse carpal ligament, resulting in increased stiffness and contributing to space limitation in the carpal tunnel

[46]. Nerve oedema, originating from an increased vascular permeability and angiogenesis, due to upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in diabetes, may also contribute to the increased susceptibility to compression trauma

[47]; a mechanism that has been related to increased endoneurial pressure with a risk of jeo-pardised blood supply to the nerve fibres in the fascicles

[48]. Nerve oedema has been demonstrated in ultrasound studies, showing that the median nerve cross-sectional area is enlarged in diabetes

[49]. Upregulation of VEGF and its receptors, but not of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α), has been demonstrated in biopsies of the posterior interosseus nerve (PIN) from patients with CTS and diabetes

[50]. The number of myelinated nerve fibres has been analysed in such biopsies of the posterior interosseous nerve, indicating that otherwise healthy subjects with CTS have a lower density of myelinated nerve fibres than those without CTS

[16]. Interestingly, patients with diabetes and CTS have an even lower density of such myelinated nerve fibres, which may explain the increased susceptibility

[16]. In accordance, subjects with HAVS also have structural changes in upper extremity nerves

[51], resulting in a higher risk for additional CTS

[17]. To conclude, diabetes may confer an increased susceptibility to the peripheral nerve, where the pathophysiological mechanisms are complex and involve both biochemical and structural alterations in the nerve.

4. Symptoms and Clinical Signs of CTS

In CTS, symptoms, clinical findings, and electrophysiology results depend on the magnitude, nature, and duration of the compression trauma. In individuals with diabetes, early signs of CTS may be mistaken for diabetic neuropathy

[52]. Basically, one may relate the pathophysiological events in the nerve to the experienced symptomatology, irrespective of whether the affected individual has diabetes or not. Initially, due to the distur-bances in intraneural microcirculation and possible dynamic ischemia by a slight compression trauma, paraesthesia, and numbness are induced in the median nerve innervated sensory area of the affected hand with worse symptoms during the night

[53]. This might be detected as a metabolic conduction block on electrophysiology testing. As the compression worsens, endoneurial oedema may form, causing increased endoneurial pressure with further microcirculatory disturbances

[54] and more constant symptoms. Eventually, the compression trauma at this stage leads to demyelination

[55][56] and at a later stage, even axonal degeneration

[57] with end-stage symptoms, such as anaesthesia and thenar atrophy

[56]. The focal demyelination can be detected on the electrophysiology examination as an increased latency with a decrease in nerve conduction velocity

[58], while axonal degeneration is reflected in a reduced amplitude

[59][60]. Patients with diabetes and CTS are twice as likely to present with advanced disease as measured by electrophysiology than those with CTS without concomitant diabetes

[61]. After surgery, with the release of the carpal ligament, recovery of patient symptoms also depends on preoperative severity. The microcirculatory disturbances recover quickly, while the structural changes may disappear slowly or incompletely. Remyelination follows the demyelination process, but remyelinated segments have thinner myelin

[62] with shorter internodal distances, observed as a permanently reduced conduction velocity. Recovery, requiring axonal regeneration in the nerve, may take longer and may be incomplete, with a reduced amplitude on the electrophysiological examination.

5. CTS and Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

In a recent study from the UK of 401,656 individuals, including 24,558 with diabetes, the odds ratio (OR) for CTS in diabetes was 2.31 (95% CI 2.17–2.46)

[63]. Similar results were presented in a Swedish cohort study of 30,466 individuals showing a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.10 (95% CI 1.65–2.70)

[14], and the pooled OR was 1.69 (1.45–1.96) in one large review controlling for confounders

[64]. A meta-analysis indicated that associations with CTS were the same in type 1 and 2 diabetes

[64], but more current research has confirmed that CTS is more common in type 1 patients (9). Incidence rates for CTS are reported to be 95.5/10,000 person-years for women and 58.1/10,000 person-years for men with type 1 diabetes, and 52.1/10,000 person-years for women and 31.6/10,000 person-years for men with type 2 diabetes

[12] (

Table 1). The higher incidence rates in type 1 diabetes may be attributed to the presence of neuropathy, which can be detected as alterations in the distribution of nerve fibres of different sizes in the posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) with more autophagy-related ultrastructures

[39].

Table 1. Risk for CTS in diabetes related to sex.

| OR (95% CI) |

Men with Diabetes |

Women with Diabetes |

| 1.99 (1.81–2.19) |

2.63 (2.42–2.86) |

| T1D |

T2D |

T1D |

T2D |

| Prevalence |

6.8% |

5.0% |

13.5% |

10.1% |

Incidence rate/

10,000 person-years |

58.1 |

31.6 |

95.5 |

52.1 |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11061674