Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam, during which fasting is obligatory for all healthy individuals. Although pregnant women are exempt from this Islamic law, the majority nevertheless choose to fast. The association between Ramadan fasting and health outcomes of offspring is not supported by strong evidence. To further elucidate the effects of Ramadan fasting, larger prospective and retrospective studies with novel designs are needed.

- fasting

- Islam

- pregnancy

- humans

- fetal development

- pregnancy outcome

- infant

- newborn

1. Introduction

2. Ramadan Fasting during Pregnancy and Health Outcomes in Offspring

2.1. Fetal Growth Indices

2.2. Birth Indices

2.3. Cognitive Effects

2.4. Long-Term Effects

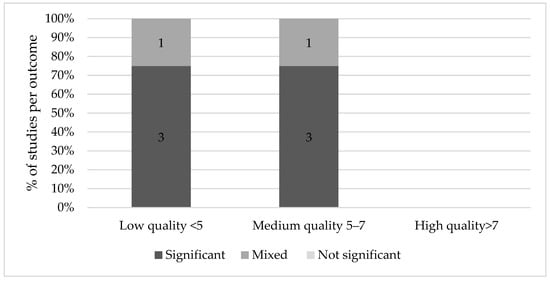

an Ewijk [42] found that Muslims prenatally exposed to Ramadan fasting had poorer general health (6.1% of a standard deviation, p < 0.01), rated by professional health workers who measured a number of health and physical indicators such as height, weight, blood pressure, hemoglobin levels and lung capacity on a 9-point scale. This effect was more pronounced in those older than 45 years (18.5%, p < 0.01) and it appeared stronger when Ramadan started in the second trimester. Alwasel et al. [43] similarly found that boys and girls of mothers exposed to Ramadan had a significantly different length and length of gestation than their counterparts in the second trimester only (p = 0.005 and p = 0.04 respectively). Based on the same Indonesian Family Life Survey, Van Ewijk and colleagues found that on average, adult Muslims who were exposed to Ramadan in mid- and late-gestation had a lower BMI because of lower weight (respectively −0.93 kg, CI 95% −1.72, −0.14 and −1.06 kg, CI 95%–1.88, −0.25) compared to those not in utero during Ramadan [44]. Furthermore, those conceived during Ramadan, in addition to thinner stature, had a smaller stature, being on average 0.80 cm shorter than those who were not exposed. Although Kunto and Mandemakers [45] discovered a similar effect of prenatal exposure to Ramadan on BMI and stature, their results were not significant. For an overview of the evidence of long-term effects of Ramadan fasting on the offspring, see Figure 4.

3. Summary

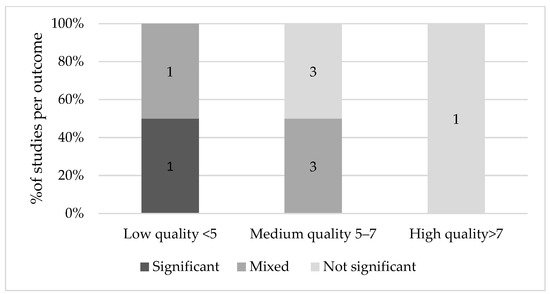

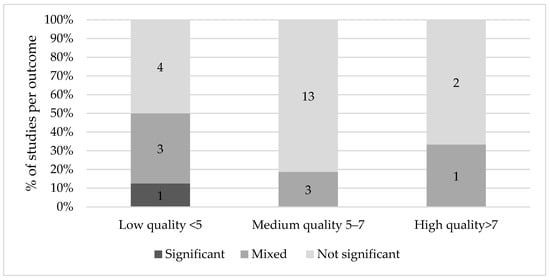

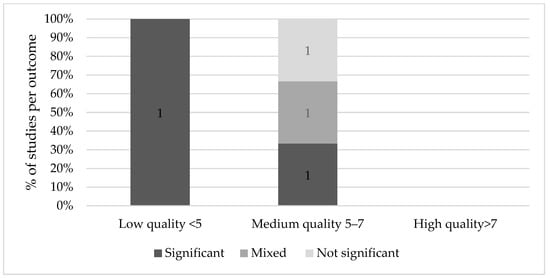

Some studies found an association between Ramadan fasting and fetal growth indices, birth indices, cognitive scores and long-term consequences. However, significant results were predominantly found in low quality studies. None of the high-quality studies reported a significant effect on fetal growth, birth, cognitive or long-term outcomes. Medium quality studies generally found mixed or non-significant results, although the majority of medium quality studies found significant results for long-term effects.

Ramadan fasting did not seem to affect the health of healthy, pregnant women nor their offspring [2][11][12]. Rouhani and Azadbakht [11] did not find significant effects, however, the researchers advised to avoid Ramadan fasting due to the limitations of the studies that were included in the review. Glazier and colleagues [13] concluded that more studies are needed to accurately determine the association with maternal and neonatal outcomes. In their systematic review and meta-analysis, they found that birth weight is not adversely affected by Ramadan fasting, but there was insufficient evidence for potential effects on other perinatal outcomes. In line with Nikoo et al. [46], no reported effect of Ramadan fasting on fetal physical and mental growth was identified. However, although most studies found no association between Ramadan fasting and fetal measures, three studies found a decreased AFI [20][21][19]. Since other fetal parameters were normal, an explanation for this decrease could be maternal dehydration as a result of high temperatures and long durations of fasting. Low amniotic fluid levels have been linked to perinatal death, fetal deformations, PTD, LBW and poor neonatal health [47][48]. For this reason, it is advisable to monitor the pregnancies of these women more closely.

Future research should investigate the effect of Ramadan fasting on cognition and long-term effects, ideally with a prospective study design that involves many participants. These prospective studies should be carefully designed, as the sociological and religious dimension of Ramadan may also alter maternal behavior to protect the belief that Ramadan has no effect on their offspring. Another promising approach to studying these effects would be enhanced retrospective study designs based on routine data collection comparing Islamic pregnant women during and outside the Ramadan period to reduce the effect of confounding but only under the condition that (Ramadan) fasting is registered in routine care, as other seasonal effects on birth outcomes may still apply such as malaria [49][50] and vitamin D status [51][52]. These types of studies are also needed in order to confirm the results of high quality studies in birth and fetal health outcomes. In addition to the frequency of eating during Ramadan, the quality of the food that women eat during the nighttime also deserves attention. In addition to these quantitative studies into the effects of Ramadan fasting, we argue for qualitative research into the communication between pregnant women and their healthcare providers in order to improve the shared decision-making processes concerning fasting during pregnancy.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13103450

References

- Adawi, M.; Watad, A.; Brown, S.; Aazza, K.; Aazza, H.; Zouhir, M.; Sharif, K.; Ghanayem, K.; Farah, R.; Mahagna, H.; et al. Ramadan Fasting Exerts Immunomodulatory Effects: Insights from a Systematic Review. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1144.

- Mirsane, S.A.; Shafagh, S. A Narrative Review on Fasting of Pregnant Women in the Holy Month of Ramadan. J. Fasting Health 2016, 4, 53–56.

- Kridli, S.A.-O. Health Beliefs and Practices of Muslim Women During Ramadan. MCN Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2011, 36, 216–221.

- Almond, D.; Mazumder, B. Health Capital and the Prenatal Environment: The Effect of Ramadan Observance During Pregnancy. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2011, 3, 56–85.

- Mirghani, H.M.; Weerasinghe, S.; Al-Awar, S.; Abdulla, L.; Ezimokhai, M. The Effect of Intermittent Maternal Fasting on Computerized Fetal Heart Tracing. J. Perinatol. 2004, 25, 90–92.

- Van Bilsen, L.A.; Savitri, A.I.; Amelia, D.; Baharuddin, M.; Grobbee, D.E.; Uiterwaal, C.S. Predictors of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2016, 6, 267–275.

- Afandi, B.O.; Hassanein, M.M.; Majd, L.M.; Nagelkerke, N.J.D. Impact of Ramadan fasting on glucose levels in women with gestational diabetes mellitus treated with diet alone or diet plus metformin: A continuous glucose monitoring study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000470.

- Hassanein, M.; Al-Arouj, M.; Hamdy, O.; Bebakar, W.M.W.; Jabbar, A.; Al-Madani, A.; Hanif, W.; Lessan, N.; Basit, A.; Tayeb, K.; et al. Diabetes and Ramadan: Practical guidelines. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 126, 303–316.

- Pathan, F. Pregnancy and fasting in women with diabetes mellitus. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2015, 65, S30–S32.

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Briki, W.; Khabbache, H.; Rammouz, I.; Chamari, K.; Demaj, T.; Re, T.S.; Zouhir, M. Ramadan Fasting and Patients with Cancer: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 27.

- Rouhani, M.H.; Azadbakht, L. Is Ramadan fasting related to health outcomes? A review on the related evidence. J. Res. Med Sci. 2014, 19, 987–992.

- Zoukal, S.; Hassoune, S. The effects of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy on fetal development: A general review. Tunis. Med. 2019, 97, 1132–1138.

- Glazier, J.D.; Hayes, D.J.L.; Hussain, S.; D’Souza, S.W.; Whitcombe, J.; Heazell, A.E.P.; Ashton, N. The effect of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 1–11.

- Rabinerson, D.; Dicker, D.; Kaplan, B.; Ben-Rafael, Z.; Dekel, A. Hyperemesis gravidarum during Ramadan. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 21, 189–191.

- Rezk, M.A.-A.; Sayyed, T.; Abo-Elnasr, M.; Shawky, M.; Badr, H. Impact of maternal fasting on fetal well-being parameters and fetal–neonatal outcome: A case–control study. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2015, 29, 2834–2838.

- Dikensoy, E.; Balat, O.; Cebesoy, B.; Ozkur, A.; Cicek, H.; Can, G. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on fetal development and maternal health. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2008, 34, 494–498.

- Hızlı, D.; Yılmaz, S.S.; Onaran, Y.; Kafalı, H.; Danışman, N.; Mollamahmutoğlu, L. Impact of maternal fasting during Ramadan on fetal Doppler parameters, maternal lipid levels and neonatal outcomes. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2011, 25, 975–977.

- Moradi, M. The effect of Ramadan fasting on fetal growth and Doppler indices of pregnancy. J. Res. Med Sci. 2011, 16, 165–169.

- Seckin, K.D.; Yeral, M.I.; Karslı, M.F.; Gultekin, I.B. Effect of maternal fasting for religious beliefs on fetal sonographic findings and neonatal outcomes. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 126, 123–125.

- Karateke, A.; Kaplanoglu, M.; Avci, F.; Kurt, R.K.; Baloglu, A. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting On Fetal Development. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 1295–1299.

- Sakar, M.N.; Gultekin, H.; Demir, B.; Bakır, V.L.; Balsak, D.; Vuruskan, E.; Acar, H.; Yucel, O.; Yayla, M. Ramadan fasting and pregnancy: Implications for fetal development in summer season. J. Périnat. Med. 2015, 43, 319–323.

- Awwad, J.; Usta, I.; Succar, J.; Musallam, K.; Ghazeeri, G.; Nassar, A. The effect of maternal fasting during Ramadan on preterm delivery: A prospective cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 119, 1379–1386.

- Kavehmanesh, Z.; Abolghasemi, H. Maternal Ramadan Fasting and Neonatal Health. J. Perinatol. 2004, 24, 748–750.

- Altunkeser, A.; Körez, M.K. The Influence of Fasting in Summer on Amniotic Fluid During Pregnancy. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2016, 6, 21.

- Daley, A.; Pallan, M.; Clifford, S.; Jolly, K.; Bryant, M.; Adab, P.; Cheng, K.K.; Roalfe, A. Are babies conceived during Ramadan born smaller and sooner than babies conceived at other times of the year? A Born in Bradford Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 722–728.

- Makvandi, S.; Nematy, M.; Karimi, L. Effects of Ramadan Fasting on Neonatal Anthropometric Measurements in the Third Trimester of Pregnancy. Fasting Health 2013, 1, 53–57.

- Ozturk, E.; Balat, O.; Ugur, M.G.; Yazicioglu, C.; Pençe, S.; Erel, O.; Kul, S. Effect of Ramadan fasting on maternal oxidative stress during the second trimester: A preliminary study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2011, 37, 729–733.

- Petherick, E.S.; Tuffnell, D.; Wright, J. Experiences and outcomes of maternal Ramadan fasting during pregnancy: Results from a sub-cohort of the Born in Bradford birth cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 335.

- Safari, K.; Piro, T.J.; Ahmad, H.M. Perspectives and pregnancy outcomes of maternal Ramadan fasting in the second trimester of pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 128.

- Sarafraz, N.; Atrian, M.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Bagheri, A. Effect of Ramadan Fasting during Pregnancy on Neonatal Birth Weight. J. Fasting Health 2014, 2, 37–40.

- Savitri, A.I.; Amelia, D.; Painter, R.C.; Baharuddin, M.; Roseboom, T.J.; Grobbee, D.E.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M. Ramadan during pregnancy and birth weight of newborns. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, e5.

- Shahgheibi, S.; Ghadery, E.; Pauladi, A.; Hasani, S.; Shahsawari, S. Effects of Fasting during Third Trimester of Pregnancy on Neonatal Growth Indices. Ann. Alquds Med. 2005, 1, 58–62.

- Cross, J.H.; Eminson, J.; Wharton, B.A. Ramadan and birth weight at full term in Asian Moslem pregnant women in Birmingham. Arch. Dis. Child. 1990, 65, 1053–1056.

- Savitri, A.I.; Yadegari, N.; Bakker, J.; Van Ewijk, R.; Grobbee, D.E.; Painter, R.C.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.M.; Roseboom, T.J. Ramadan fasting and newborn’s birth weight in pregnant Muslim women in The Netherlands. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1503–1509.

- Sarafraz, N.; Abbaszadeh, F.; Bagheri, A.; Atrian, M.K. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting On Neonatal Weight In Different Trimesters Of Pregnancy. Health Spiritual. Med. Ethics 2015, 2, 16–24.

- Ziaee, V.; Kihanidoost, Z.; Yunesian, M.; Akhavirad, M.-B.; Bateni, F.; Kazemianfar, Z.; Hantoushzadeh, S. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Outcome of Pregnancy. Iran. J. Pediatr. 2010, 20, 181–186.

- Sakar, M.N.; Balsak, D.; Verit, F.F.; Zebitay, A.G.; Buyuk, A.; Akay, E.; Turfan, M.; Demir, S.; Yayla, M. The effect of Ramadan fasting and maternal hypoalbuminaemia on neonatal anthropometric parameters and placental weight. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 36, 483–486.

- Jamilian, H.; Jamilian, M.; Hekmat Po, D.; Shamsi, M.; Ardalan, S. The Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Outcome of Pregnancy. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2015, 23, 1270–1275.

- Azizi, F.; Sadeghipour, H.; Siahkolah, B.; Rezaei-Ghaleh, N. Intellectual Development of Children Born of Mothers who Fasted in Ramadan during Pregnancy. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2004, 74, 374–380.

- Majid, M.F. The persistent effects of in utero nutrition shocks over the life cycle: Evidence from Ramadan fasting. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 117, 48–57.

- Almond, D.; Mazumder, B.; Van Ewijk, R. In UteroRamadan Exposure and Children’s Academic Performance. Econ. J. 2014, 125, 1501–1533.

- van Ewijk, R. Long-term health effects on the next generation of Ramadan fasting during pregnancy. J. Health Econ. 2011, 30, 1246–1260.

- Alwasel, S.; Abotalib, Z.; Aljarallah, J.; Osmond, C.; Alkharaz, S.; Alhazza, I.; Harrath, A.; Thornburg, K.; Barker, D. Sex Differences in birth size and intergenerational effects of intrauterine exposure to Ramadan in Saudi Arabia. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 651–654.

- Van Ewijk, R.J.G.; Painter, R.C.; Roseboom, T.J. Associations of Prenatal Exposure to Ramadan with Small Stature and Thinness in Adulthood: Results From a Large Indonesian Population-Based Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 177, 729–736.

- Kunto, Y.S.; Mandemakers, J.J. The effects of prenatal exposure to Ramadan on stature during childhood and adolescence: Evidence from the Indonesian Family Life Survey. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2018, 33, 29–39.

- Nikoo, M.K.; Shadman, Z.; Larijani, B. Ramadan Fasting, Pregnancy and Lactation. Iran. South Med. J. 2014, 17, 99–106.

- Casey, B.M.; McIntire, D.D.; Bloom, S.L.; Lucas, M.J.; Santos, R.; Twickler, D.M.; Ramus, R.M.; Leveno, K.J. Pregnancy outcomes after antepartum diagnosis of oligohydramnios at or beyond 34 weeks’ gestation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 182, 909–912.

- Brace, R.A. Physiology of Amniotic Fluid Volume Regulation. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1997, 40, 280–289.

- Chua, C.L.L.; Hasang, W.; Rogerson, S.J.; Teo, A. Poor Birth Outcomes in Malaria in Pregnancy: Recent Insights Into Mechanisms and Prevention Approaches. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12.

- Nkwabong, E.; Mayane, D.N.; Meka, E.; Essiben, F. Malaria in the third trimester and maternal-perinatal outcome. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 151, 103–108.

- Dror, D.K.; Allen, L.H. Vitamin D inadequacy in pregnancy: Biology, outcomes, and interventions. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 465–477.

- Zhou, S.-S.; Tao, Y.-H.; Huang, K.; Zhu, B.-B.; Tao, F.-B. Vitamin D and risk of preterm birth: Up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 247–256.