The term coronary “artery vasculitis” is used for a diverse group of diseases with a wide spectrum of manifestations and severity. Clinical manifestations may include pericarditis or myocarditis due to involvement of the coronary microvasculature, stenosis, aneurysm, or spontaneous dissection of large coronaries, or vascular thrombosis. As compared to common atherosclerosis, patients with coronary artery vasculitis are younger and often have a more rapid disease progression. Several clinical entities have been associated with coronary artery vasculitis, including Kawasaki’s disease, Takayasu’s arteritis, polyarteritis nodosa, ANCA-associated vasculitis, giant-cell arteritis, and more recently a Kawasaki-like syndrome associated with SARS-COV-2 infection.

- coronary artery disease

- vasculitis

- inflammatory diseases

1. Introduction

2. Most Common Vasculitis Entities with Coronary Involvement

| Group and Disease | Laboratory Findings | Frequency of Coronary Involvement | Location | Typical Lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Vessels | ||||

| Takayasu [6,7] | Inflammatory markers | 10–45% | Ostial/proximal | Stenosis |

| Giant cell arteritis [8] | Inflammatory markers | Rare | Diffuse | Tapered smooth narrowings |

| Medium Vessels | ||||

| Polyarteritis nodosa [9,10] | Not consistently | 10–50% | Not specific | Aneurysm or stenosis |

| Kawasaki [11,12] | Inflammatory markers | 25–30% | Not specific | Aneurysm > stenosis |

| Small vessel | ||||

| Eosinophilic angiitis [10] | ANCA (not in all forms) | Rare | Not specific | Stenosis or aneurysm |

| Veins > arteries | ||||

| Behçet [13,14,15,16] | Not consistently | 0.5–2% | Not specific | Thrombosis or pseudoaneurysm |

| Variable | ||||

| Erdheim–Chester [17] | Rare | 25–55% | Right coronary prevalent | Periarteritis |

| IgG4 [18] | IgG4 | 1–3% | Not specific | Aneurysm or periarteritis |

2.1. Large Vessel Vasculitis

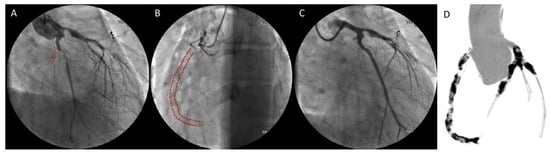

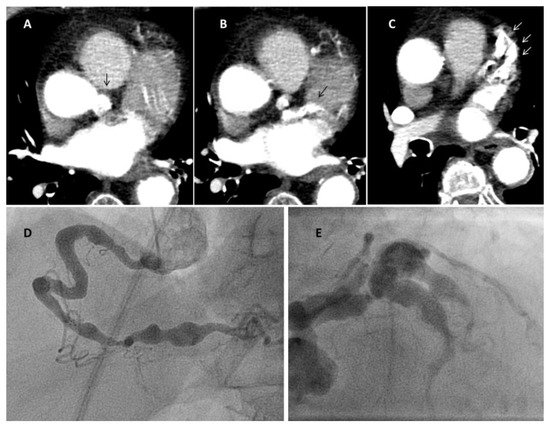

2.1.1. Takayasu

2.1.2. Giant Cell Arteritis

2.2. Medium Vessel Vasculitis

2.2.1. Polyarteritis Nodosa

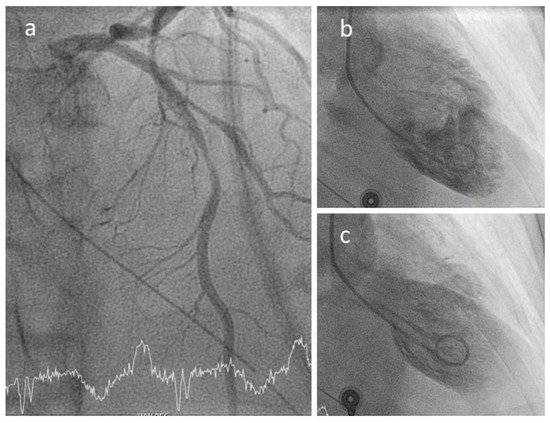

2.2.2. Kawasaki

2.3. Small Vessel Vasculitis

Eosinophilic Angiitis

2.4. Other Forms

2.4.1. Behçet

2.4.2. Erdheim–Chester Disease

2.4.3. IgG4-Related Disease

3. Epidemiology

4. Pathogenesis and Pathology

5. Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

6. COVID-19 and Coronary Inflammation

COVID and Kawasaki-Like Disease

7. Revascularization Procedures in Coronary Artery Vasculitis

7.1. Chronic Coronary Syndromes

7.2. Acute Coronary Syndromes

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines9060622