Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs), usually found and isolated from the T cell zone of lymph nodes, have recently been described as much more than simple structural cells.

- fibroblastic reticular cells

- T cells

- lymph nodes

1. Overview

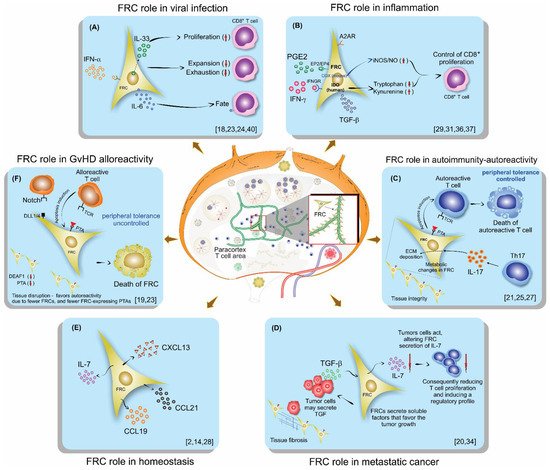

Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs), usually found and isolated from the T cell zone of lymph nodes, have recently been described as much more than simple structural cells. Originally, these cells were described to form a conduit system called the “reticular fiber network” and for being responsible for transferring the lymph fluid drained from tissues through afferent lymphatic vessels to the T cell zone. However, nowadays, these cells are described as being capable of secreting several cytokines and chemokines and possessing the ability to interfere with the immune response, improving it, and also controlling lymphocyte proliferation. Here, we performed a systematic review of the several methods employed to investigate the mechanisms used by fibroblastic reticular cells to control the immune response, as well as their ability in determining the fate of T cells. We searched articles indexed and published in the last five years, between 2016 and 2020, in PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane, following the PRISMA guidelines. We found 175 articles published in the literature using our searching strategies, but only 24 articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria and are discussed here. Other articles important in the built knowledge of FRCs were included in the introduction and discussion. The studies selected for this review used different strategies in order to access the contribution of FRCs to different mechanisms involved in the immune response: 21% evaluated viral infection in this context, 13% used a model of autoimmunity, 8% used a model of GvHD or cancer, 4% used a model of Ischemic-reperfusion injury (IRI). Another four studies just targeted a particular signaling pathway, such as MHC II expression, FRC microvesicles, FRC secretion of IL-15, FRC network, or ablation of the lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-producing ectoenzyme autotaxin. In conclusion, our review shows the strategies used by several studies to isolate and culture fibroblastic reticular cells, the models chosen by each one, and dissects their main findings and implications in homeostasis and disease.

2. Background

3. Conclusions

| Ref. | Year | Host | Interventions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Genotype | Age (Weeks) | Gender | Type | Time (Days) | ||

| Aparicio-Domingo et al. [18] | 2020 | Mice C57BL/6J | IL-33gfp/gfp; IL-33gfp/+ | 7–19 | M | LCMV clone 13 and WE virus; tamoxifen | Single dose; 6 (3/week) |

| Dertschnig et al. [19] | 2020 | Mice C57BL/6 | Female to male bone marrow transplant model (BMT), T cell-depleted, plus transgenic TCR-CD8 MataHari (Mh) | NR | M | Dexamethasone; DT; Gy irradiation | 3; 4 |

| Eom et al. [20] | 2020 | Human | Metastatic melanoma and surgery | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gonzalez et al. [21] | 2020 | Mice (NOD/ShiLtJ, NOR/LtJ, and NOD.CgTg); Human | Type 1 diabetes |

12 | F | NA | NA |

| Knop et al. [22] | 2020 | Mice C57BL/6N and ROSA26RFP | IL-7−/−, PGK-Cre, FLPO, RAG1−/−, Thy1.1+ OT-I | NR | NR | NA | NA |

| Perez-Shibayama et al. [23] | 2020 | Mice C57BL/6 | CCL19-Cre IFNARfl/fl | 8–10 | NR | LCMV Armstrong | NR |

| Brown et al. [24] | 2019 | Mice C57BL/6 | IL-6−/−; NOS2−/− | 5–12 | M | PR8-GP33-41, LCMV, influenza, OT-1 T cells with OVA | NR |

| Kasinath et al. [25] | 2019 | Mice CD-1 IGS or C57BL/6 or C57BL/6J | CCL19-Cre iDTR | 8–10 | M | Nephrotoxic serum (NTS); DT | 3 |

| Kelch et al. [26] | 2019 | Mice C57BL/6J | NA | 9–22 | M | NA | NA |

| Majumder et al. [27] | 2019 | Mice C57BL/6 | IL-17A−/−; IL-17RAfl/fl; OT-II, ACT1−/−; CCL19-Cre; IL23R−/−; Regnase1+/- | 6–12 | M-F | MOG with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, pertussis toxin on/OT-II CD4+ T cells with OVA/DSS | 2 |

| Masters et al. [28] | 2019 | Mice C57BL/6 | RAG−/−; CD45.1 | 2–4 m and 19–21 m | M | Influenza | NR |

| Schaeuble et al. [29] | 2019 | Mice C57BL/6 | NOS2−/−; OT-1; COX2−/−, COX2ΔCCL19Cre, and ROSA26-EYFPCCL19Cre | ≥6 | NR | OVA and poly (I:C) | 4 |

| Dubrot et al. [30] | 2018 | Mice C57BL/6 | CIITA−/−; pIV−/−; K14 TGP IVKO; RAG2−/− PROX-1-Cre MHC-IIfl | >12m | NR | Tamoxifen; IFN-γ and FTY720 | 4 (Twice/day); 6 |

| Knoblich et al. [31] | 2018 | Human | Cadaveric donors | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Maaraouf et al. [32] | 2018 | Mice C57BL/6 | CCL19-Cre; iDTR; RAG1−/− | NR | NR | DT; LTβr-Ig | 1; 2 |

| Chung et al. [33] | 2017 | Mice BALB/c or C57BL/6 | TgMx1-Cre; DLL1fl/fl; DLL4fl/fl; NOTCH2fl/fl; RAG1−/− | 6–10 or 8–12 | M-F | poly (I:C)/8.5-9 Gy; poly (I:C)/6 Gy irradiation |

0.16; 0.12 |

| Gao et al. [34] | 2017 | Mice C57BL/6 and Human | Colon cancer | 6 | F | Lewis Long carcinoma cells | NA |

| Pazstoi et al. [35] | 2017 | Mice BALB/c | FOXP3hCD2xRAG2−/− xD011.10 | NR | M-F | NA | NA |

| Valencia et al. [36] | 2017 | Human | Brain-dead organ donors | NA | M-F | NA | NA |

| Yu, M. et al. [37] | 2017 | Mice C57BL/6 and Human | PTGS2Y385F/Y385F; OVA-specific CD8 (OT-I); CD4 (OT-II) | 4–6 | NR | DC-vaccine | 1.5 |

| Gil-Cruz et al. [38] | 2016 | Mice C57BL/6N or C57BL/6N-Tg or R26R-EYFP | Myd88−/−; TLR7−/−; CCL19-Cre | 8–10 | NR | MHV A59; Citrobacter rodentium | 12; 6 |

| Novkovic et al. [39] | 2016 | Mice C57BL/6N or C57BL/6N-Tg | CCL19-Cre; iDTR | 6–9 | NR | DT | 3 and 5 |

| Royer et al. [40] | 2016 | Mice C57BL/6 or Gbt-1.1 | CXCL10−/−; CXCR3−/−; STING−/−; CD18−/− | 6–12 | M-F | HSV-1 | NR |

| Takeda et al. [41] | 2016 | Mice C57BL/6J | LPAR2−/−; ENPP2-flox, CCCL19-Cre, LPAR5−/−; LPAR6−/− | 8–12 | NR | CD4+ T cells labeled with CMTMR; LTβR-Fc | 0.6; 1.04; 28 |

| Ref. | Lymph Node Region | Digestion Type | Digestion Solution | FRC Culture Medium + Supplement | FRC Immunophenotypic Characterization | Technique for Cell Separation | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparicio-Domingo et al. [18] | Axillary; brachial; inguinal | Enzymatic | Collagenase IV; DNase I; CaCl2 | DMEM (2% FCS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | >94 |

| Dertschnig et al. [19] | Peripheral; mesenteric | Enzymatic | DNase; Liberase | NC | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Eom et al. [20] | Axillary; inguinal; cervical; mesenteric; mediastinum | Enzymatic | DNase I; Liberase DH | RPMI-1640 | CD45, CD31, PDPN | NR | NR |

| Gonzalez et al. [21] | Skin-draining (brachial; axillary; inguinal); Pancreatic | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; DNase I; Dispase II | NR | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Knop et al. [22] | Peripheral; mesenteric | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; Dispase II; DNase I; Latrunculin B | RPMI-1640 | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | >73.3 |

| Perez-Shibayama et al. [23] | Inguinal | Enzymatic | Collagenase F; DNase I | RPMI | NR | NR | NR |

| Brown et al. [24] | NR | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; DNase I; Dispase | α-MEM | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | >95 |

| Kasinath et al. [25] | Kidney | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kelch et al. [26] | Popliteal; mesenteric; Inguinal | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Majumder et al. [27] | Mesenteric; inguinal | Enzymatic | DNase I; Liberase; Dispase | RPMI | CD45; CD31; PDPN; | Microbeads isolation | >98 |

| Masters et al. [28] | Mesenteric; popliteal |

Enzymatic | Liberase TL; Benzonuclease | RPMI-1640 | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Microbeads isolation | >90 |

| Schaeuble et al. [29] | Peripheral (axillary, brachial, inguinal) | Enzymatic | Collagenase IV; DNase I | DMEM (2% FCS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Microbeads isolation | ≥90 |

| Dubrot et al. [30] | Skin-draining | Enzymatic | Collagenase D; DNase I | HBSS | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Knoblich et al. [31] | NR | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; DNase I; Dispase | α-MEM (10% FBS) | CD45; PDPN | NR | 99 |

| Maaraouf et al. [32] | Kidney | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; DNase I; Dispase II | DMEM (10% FBS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | NR | NR |

| Chung et al. [33] | Peripheral (cervical, axial, brachial, inguinal) | Enzymatic | Collagenase IV; DNase I | DMEM (2% FBS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Gao et al. [34] | Inguinal | Enzymatic | Collagenase IV; DNase I | RPMI-1640 (2% FBS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | NA | NA |

| Pazstoi et al. [35] | Mesenteric | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; Dispase; DNase I | RPMI-1640 | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | 91–97 |

| Valencia et al. [36] | Mesenteric | Mechanical disruption | NR | RPMI-1640 | CD45, CD31, PDPN | NR | NR |

| Yu, M. et al. [37] | Axillary; brachial; inguinal | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; Dispase; DNase I | DMEM (10% FBS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | >95 |

| Gil-Cruz et al. [38] | Mesenteric | Enzymatic | Collagenase D; DNase I | RPMI-1640 (2% FCS) | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Novkovic et al. [39] | Inguinal | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; DNase I | RPMI (2% FCS) | PDPN | NA | NA |

| Royer et al. [40] | Mandibular | Mechanical disruption | NR | RPMI-1640 (10% FBS) | NR | NR | NR |

| Takeda et al. [41] | Mesenteric; peripheral; brachial | Enzymatic | Collagenase P; Dispase; DNase I | RPMI-1640 | CD45; CD31; PDPN | Cell sorting | NR |

| Ref. | Source of Cells | Cell Type | Separation Technique | Immune Cell Preservation Solution and Supplementation | Immune Cell Immunophenotypic Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparicio-Domingo et al. [18] | LN | CD8+ T cells | Non selection performed | DMEM (2% FCS) | CD45, CD8α, CD4, TRCαβ |

| Dertschnig et al. [19] | LN | T cells | CD3 negative selection followed by CD4 and CD8α positive selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) |

NR | CD45, CD45.1, CD3, CD4, CD8α, CD62L, CD44, CD69, CD127, Vα2, Vβ5 |

| Eom et al. [20] | LN | NA | NA | NA | CD45, CD3, CD8 |

| Gonzalez et al. [21] | Spleen | CD8+ T cells | CD8 isolation by negative selection (Microbeads—MojoSort) | NR | CD45, CD8, CD44, CD25 |

| Knop et al. [22] | LN; spleen | T cells and NK | CD8α positive selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) | RPMI | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8α, CD62L, Bcl-2, CD127, Nk1.1, RORγt |

| Perez-Shibayama et al. [23] | LN; spleen | T cell subsets and exhaustion | No selection performed | RPMI | CD45.1, CD45.2, CD45R, CD8α, CD8β, CD3e, CD44 CD62L, PD-1, PDL1 |

| Brown et al. [24] | LN | CD8+ T cells | CD8α positive selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) | RPMI; α-MEM | CD45.1, CD45.2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD275, CD28, CD44 |

| Kasinath et al. [25] | LN; spleen | CD4+ T cells | No selection performed | NR | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD44, CD62L, IL-17A |

| Kelch et al. [26] | LN | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Majumder et al. [27] | LN | T and B cells | NR | NR | CD45, CD45.2, CD4, B220, IL-17A, IL-17R |

| Masters et al. [28] | LN; peripheral blood | CD8+ T | CD8 isolation by negative selection (Microbeads—MojoSort) | NR | CD45, CD45.1, CD45.2, CD69, CD8α |

| Schaeuble et al. [29] | LN; spleen | T cells | No selection performed | RPMI | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8α, CD44, CD62L, CD279, FoxP3, CD25 |

| Dubrot et al. [30] | LN; spleen | T cells, B cells, Treg, and DC | Pan T isolation by negative selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) |

NR | CD45, CD44, CD3, CD4, CD8α, FOXp3, Ly5.1, CD11b, CD19, CD25, CD62L, PDCA-1, PD-1, IL-17, IFNγR |

| Knoblich et al. [31] | LN; tonsils | T cells | Pan T isolation by negative selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) |

NR | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD62L, CD27, CD45RO, CD25 |

| Maaraouf et al. [32] | Spleen | T cells | Pan T isolation by negative selection (MicroBeads—Myltenyi) |

NR | CD45, CD4 |

| Chung et al. [33] | Spleen; peripheral blood | T cells, B cells, FDCs, Treg, and DCs | T cell Thy.1 selection (Microbeads—StemCells Technologies) |

NA | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, FOXp3, CD157, CD19, B220, CD44, CD62L, CD11c, CD11b, CD169, CD21/35, F4/80, TCRβ |

| Gao et al. [34] | LN | T cells | NR | NR | CD45, CD4, CD8 |

| Pazstoi et al. [35] | LN | T cells | CD4 positive selection (Microbeads—Myltenyi) |

EX VIVO | CD45, CD45.2, CD4, CD2, CD9, CD24, CD25, CD63 |

| Valencia et al. [36] | LN | CD4+ T cells | CD4 naïve T cell negative selection (Microbeads—Myltenyi) |

RPMI (10% FCS) | CD45, CD44, CD4 |

| Yu, M. et al. [37] | LN | T cells | Pan T cell negative selection (Microbeads—StemCells Technologies) |

RPMI (10% FBS) | CD45, CD45.1, CD45.2, CD3, CD4, CD8α, CD25, CD69, CD44 |

| Gil-Cruz et al. [38] | PP; LN | T cells, B cells, NK cells, Treg, and ILCs | NR | RPMI (10% FCS) | CD45, CD3e, CD4, CD8α, EOMES, FoxP3, B220, CD19, CD127, CD62L, CD44, CD69, F4/80, IL-17A, IL-7Rα, GATA3, RORγt, IL-15RαIL-15Rβ, NKp46, NK1.1 |

| Novkovic et al. [39] | LN; Spleen | DCs and T cells | NR | RPMI (2% FCS) | CD45, CD3, CD8, CD4, CD11c, MHCII |

| Royer et al. [40] | SLOs | CD8+ T cells | CD8 positive selection (Microbeads—Myltenyi) | RPMI (10% FBS) | CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8 |

| Takeda et al. [41] | LN; Spleen | T cells, B cells | CD4 naïve T cell negative selection (Microbeads—Myltenyi) |

RPMI | CD4, CD8, B220, CD44 |

| Ref. | Trial Types | Study Target | Time of Intervention | Main Performed Evaluations | Results | FRC Role in Immune Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aparicio-Domingo et al. [18] | IL-33-GFP reporter mice | LCMV | 3 days/w for 2 weeks |

FC and RNA sequencing | FRC is one important IL-33 source in LNs, vital for driving acute and chronic antiviral T cell responses. | Anti-viral response |

| Dertschnig et al. [19] | FRC and DC ablation in vivo; identification of PTA regulatory genes; BTM model induction | GvHD | 2 weeks | FC, RNA sequencing, confocal microscopy | The loss of PTA presentation by FRCs during GVHD leads to permanent damage in their networks in lymphoid tissues. | Control of peripheral tolerance |

| Eom et al. [20] | Identification of distinctive subpopulations of CD90+ SCs present in melanoma-infiltrated LNs |

Melanoma | NA | FC, gene expression | There are several distinct subsets of FRCs present in melanoma-infiltrated LNs. These FRCs may be related to cancer metastasis invasion and progression by avoiding T cells through secreted factors. | Lymph node invasion metastasis and its correlation with FRC gene expression. |

| Gonzalez et al. [21] | Tissue-engineered stromal reticula and FRC/T cell co-culture | Type 1 diabetes |

NA | FC, immunofluorescence, imaging | FRCs modulate their interactions with autoreactive T cells by remodeling their reticular network in LNs. FRC with decreased contractility through gp38 downregulation, can loosen/relax their network, potentially decreasing FRC tolerogenic interactions with autoreactive T cells and promoting their escape from peripheral regulation in LNs. | Role of FRCs on tolerance and T1D |

| Knop et al. [22] | IL-7fl/fl mice and adoptive T cell transfer | NA | NA | FC | IL7, produced by LN FRCs-regulated T cell homeostasis, is crucial for TCM maintenance. | IL7 produced by LN FRCs is crucial for TCM maintenance |

| Perez-Shibayama et al. [23] | LCMV-infected mice, FRC ex vivo restimulation and cytokine production | LCMV Armstrong | 8 d | FC | IFNAR-dependent shift of FRC subsets toward an immunoregulatory state reduces exhaustive CD8+ T cell activation. | IFN type 1 influences FRC peripheral tolerance |

| Brown et al. [24] | FRC/T cell co-cultures | Influenza and LCMV infection | NR | FC and RNA sequencing | FRCs play a role over restricting T cell expansion—they can also outline the fate and function of CD8+ T cells through their IL-6 production. | FRCs influence the CD8 T cells fate |

| Kasinath et al. [25] | Mouse FRC depletion and treatment with anti-PDPN antibody | Crescentic Glomerulonephritis (GN) | 3 d | FC and gene expression | Removal of kidney-draining lymph nodes, depletion of fibroblastic reticular cells, and treatment with anti-podoplanin antibodies each resulted in the reduction of kidney injury in GN. | Role of FRCs and PDPN expression in GN |

| Kelch et al. [26] | 3D imaging and topological mapping | NA | NA | EVIS imaging and confocal microscopy | T cell zones showed homogeneous branching, conduit density was significantly higher in the superficial T cell zone compared with the deep zone. Although the biological significance of this structural segregation is still unclear, independent reports have pointed to an asymmetry in cell positioning in both zones. Naive T cells tend to occupy the deep TCZ, whereas memory T cells preferentially locate to the superficial zones, and innate effector cells can often be found in the interfollicular regions. |

FRC conduits and their distribution inside LNs |

| Majumder et al. [27] | Metabolic assay | Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis | 7 d | FC, immunoblotting, siRNA transfection | During Th17 differentiation in LNs, IL-17 signals to FRCs and impacts LN stromal organization by promoting FRC activation through a switch on their phenotype from quiescence to highly metabolic. | FRCs are impacted by metabolic alterations driven by IL-17 |

| Masters et al. [28] | FRC-mediated T cell proliferation inhibition and T cell survival assays | Aging and influenza infection | NR | FC | Age-related changes in LN stromal cells may have the largest impact on the initiation of the immune response to influenza infection, and may be a factor contributing to delayed T cell responses to this virus. | Aging impacts the adaptive anti-viral immune response initiation in LN |

| Schaeuble et al. [29] | Nos2−/−, COX2−/− mice and FRC/T cell co-culture | COX/Prostaglandin E2 pathway | 4 d | FC | FRCs constitutively express high levels of COX2 and its product PGE2, thereby identified as a mechanism of T cell proliferation control. | PGE2 and COX2 pathways in FRCs are implicated in the control of T cell proliferation |

| Dubrot et al. [30] | Adoptive transfer T cells in RAG−/− mice and Treg suppression assay | MHC II-induced expression by FRC and LEC and its impact on autoimmunity | 5 d | FC | LNSCs inhibit autoreactive T-cell responses by directly presenting antigens through endogenous MHCII molecules. | Control of peripheral tolerance in autoimmunity |

| Knoblich et al. [31] | T cell and CAR T cell activation assay | COX/Prostaglandin E2, iNOS, IDO and TGF-β pathways in FRCs, | NA | FC and RNA sequencing | FRCs block proliferation and modulate differentiation of newly activated naïve human T cells, without requiring T cell feedback. | FRCs used several pathways to control T cell proliferation |

| Maaraouf et al. [32] | FRC labeling and injection into mice | Ischemic-reperfusion injury (IRI) | NR | FC, electron and confocal microscopy | Depletion of FRCs reduced T cell activation in the kidney LNs and ameliorated renal injury in acute IRI. | Role of FRCs in IRI |

| Chung et al. [33] | FRC/T cell co-culture | GvHD | 4 h and 3 h | FC | FRCs delivered NOTCH signals to donor alloreactive T cells at early stages after allo-BMT to program the pathogenicity of these T cells. | Role of FRC NOTCH-signaling in activating alloreactive T cells |

| Gao et al. [34] | FRC expression and secretion of Interleukin 7 | Tumor-draining LNs | NA | FC | LN tumor-infiltrating cells decreased the FRC population and IL-7 secretion, leading to declined numbers of T cells in TDLNs. This may partly explain the weakened ability of immune surveillance in TDLNs. | Role of IL-7 secretion by FRCs and its impact on tumor-draining LNs |

| Pazstoi et al. [35] | Treg induction in presence of FRC microvesicles. | FRC microvesicles (MVEs) | NA | FC and RNA sequencing | Stromal cells originating from LNs contributed to peripheral tolerance by fostering de novo Treg induction by MVEs carrying high levels of TGF-β. | Role of FRC MVEs in inducing peripheral tolerance |

| Valencia et al. [36] | FRC/T cell co-culture | COX 2/Prostaglandin E2, iNOS, IDO and TGF-β pathways in FRCs | 6 h | FC | COX2 expression was detected in human FRCs but was not considerably upregulated after inflammatory stimulation, concluding that human and murine FRCs would regulate T lymphocytes responses using different mechanisms. | Role of FRCs integrating innate and adaptive immune responses and balancing tolerance and immunogenicity |

| Yu, M. et al. [37] | FRC/T cell co-culture | COX 2/Prostaglandin E2 pathway in FRCs | NA | FC, WB | Hyperactivity of COX-2/PGE2 pathways in FRCs is a mechanism that maintains peripheral T cell tolerance during homeostasis. | PGE2 and COX2 pathways in FRCs are implicated in the control of T cell proliferation. |

| Gil-Cruz et al. [38] | ILC1 and NK cells regulation | FRC secretion of IL-15 | 3 h | FC | FRC secretion of IL-15 regulates homeostatic ILC1 and NK cell maintenance. | Role of FRCs in innate in immunity |

| Novkovic et al. [39] | FRC network topological analysis | FRC network | NA | Intravital TPM with morphometric 3D reconstitution analysis. | Physical scaffold of LNs formed by the FRC network is critical for the maintenance of LN functionality. | FRC network disruption impacts the immune response |

| Royer et al. [40] | Adoptive transfer of T cells and T cell response to herpesvirus-associated lymphadenitis | HSV-1 | 4 h | FC | Dissemination of the virus to secondary lymphoid organs impairs HSV-specific CD8+ T cell responses by driving pathological alterations to the FRCs conduit system, resulting in fewer HSV-specific CD8+ T cells in circulation. | Role of FRC in virus-specific T CD8 response |

| Takeda et al. [41] | Lymphocyte migration | Ablation of LPA-producing ectoenzyme autotaxin in FRCs | NA | FC, IMS, Intravital TPM | LPA produced by LN FRCs acts locally to LPA2 to induce T cell motility. | Role of FRCs in T cell local migration |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells10051150