Neuralgic amyotrophy, also called Parsonage–Turner syndrome, in its classic presentation is a brachial plexopathy or a multifocal neuropathy, involving mainly motor nerves of the upper limb with a monophasic course. Recently, a new radiological entity was described, the hourglass constriction, which is characterized by a very focal constriction of a nerve, or part of it, usually associated with nerve thickening proximally and distally to the constriction. Another condition, which is similar from a radiological point of view to hourglass constriction, is nerve torsion. The pathophysiology of neuralgic amyotrophy, hourglass constriction and nerve torsion is still poorly understood, and a generic role of inflammation is proposed for all these conditions.

1. Introduction

Neuralgic amyotrophy (NA), also called Parsonage–Turner syndrome, in its classic presentation is a brachial plexopathy or a multifocal neuropathy involving mainly motor nerves of the upper limb with a monophasic course [

1,

2,

3]. However, from the original report of Parsonage and Turner in 1948, different clinical phenotypes were included in the syndrome. Variants include lower limb plexopathies, sensory–motor involvement and mononeuropathies of different nerves, such as the radial, median, anterior and posterior interosseous and phrenic nerves [

4]. Autoimmune, genetic, infectious and mechanical processes are thought to be involved, but etiopathogenesis is still incompletely understood [

1].

2. NA, Hourglass Constriction and Nerve Torsion

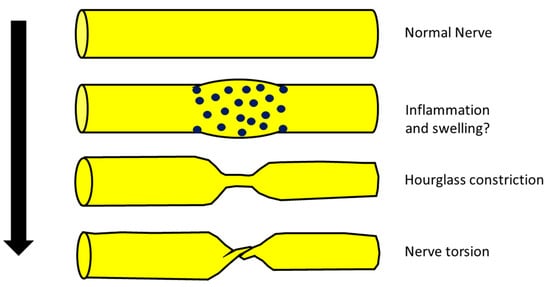

Some authors recently hypothesized that some cases of NA, after a first phase characterized by nerve inflammation and swelling, in particular anatomical conditions, could evolve into hourglass constriction and/or in nerve torsion [

8,

20] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Possible scheme of evolution from a normal nerve, trough inflammation and swelling mediated by mononuclear inflammatory infiltration (blue dots) to hourglass constriction and nerve torsion.

However, evidence of this evolution is still lacking since there are no documented cases that have progressed from swelling into hourglass constriction. In other words, there have been no cases diagnosed as NA with initial evidence of nerve swelling at neuroimaging evolving into hourglass constriction or nerve torsion at the same site where previously there was only the swelling. This would be final and decisive proof of the model proposed before. Hence, the hypothesis that hourglass constriction is a particular subtype of NA, even if interesting, is still only a suggestion.

- (a)

-

Typical NA is characterized by brachial plexus involvement, while hourglass constriction and nerve torsion are mainly found in the radial nerve, PIN and AIN [

21,

22,

23]. Hence, the topography of typical involvement is clearly different.

- (b)

-

The classic clinical phenotype of NA is characterized by strong and invalidating pain that, on the other hand, is not the main feature of hourglass constriction (some pain or sensory symptoms are usually present but not invalidating) [

2,

24].

- (c)

-

From a neurophysiological point of view, the typical picture of NA is the main or exclusive involvement of motor fibers, even in the case of mixed nerve involvement. On the other hand, hourglass constriction/nerve torsion usually affects both motor and sensory fibers at the same time and with the same severity. Motor fibers are exclusively included only in the case of pure motor nerve involvement (e.g., PIN and AIN) [

25,

26].

- (d)

-

Classic NA is historically associated with a spontaneous and quite good prognosis, while hourglass constriction/nerve torsion is usually associated with a bad prognosis, unless neurosurgical treatment is undergone [

8,

27].

3. Best Diagnostic Approach for These Conditions

3.1. Neuroimaging

It is now well accepted that nerve imaging is necessary for identifying hourglass constrictions/nerve torsion pre-surgically in patients with acute mononeuropathy/plexopathy. Ultrasound (US) is a very reliable and cost-effective technique which carries a high rate of identification and localization of the constriction [

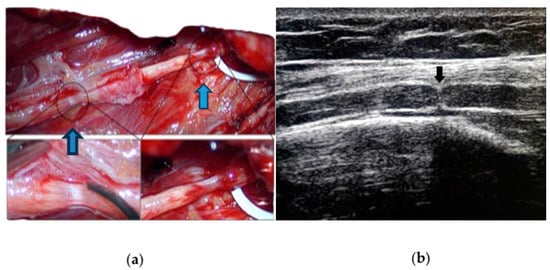

30]. It is a useful tool for diagnosis, and it is consistent with intraoperative findings, as shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2. (

a) Intraoperative appearance of spontaneous (blue arrows) double left radial nerve constriction; (

b) preoperative ultrasound of the same nerve (black arrow) showing a typical hourglass constriction, with the indentation of the hyperechoic epifascicular epineurium.

In hourglass constriction when following the nerve course with a transverse scan, there is a sudden and usually marked reduction in the nerve cross-sectional area, usually accompanied by the hyperechoic aspect of the nerve with loss of fascicular structure. Proximally and distally to this site, the cross-sectional area of the nerve is usually increased. At this level, the fascicles are usually increased in size with an aspect varying from hypo- to hyperechoic, probably according to the prevalence of oedema and fibrosis.

Longitudinal scans show the typical appearance of an hourglass-like lesion [

31,

32]. Nevertheless, US may fail to identify the constriction if the involved nerve is too deep or located under the bones or other body structures blocking the ultrasound beam. Moreover, the assessment is highly operator-dependent. MRI, particularly 1.5 and 3 Tesla scanning, has an important role [

33], although it is more expensive, more time-consuming and not widely available in clinical practice. As in the case of US, MRI is highly operator-dependent, especially when it comes to the choice of the appropriate protocol (this can also be quite time-consuming) and imaging interpretation. It can immediately show, proximal to the constriction site, peripheral signal hyperintensity and central hypointensity on intermediate-weighted FSE and/or fat-suppressed imaging, orthogonal to the longitudinal axis of the nerve (“bullseye sign”) [

34].

3.2. Neurophysiology

Neurophysiology should be performed in all cases and is necessary to confirm the clinical diagnosis in terms of location of the damage and type of nerve damage (demyelination vs. axonal vs. conduction block). Moreover, a broad examination can detect subclinical involvement of more nerves, guiding the diagnosis toward vasculitis or a genetic or inflammatory neuropathy. The correct identification of the pathology and type of damage is of the uttermost importance for the prognosis and guiding treatment as well. The neurophysiological correlate of hourglass constriction is still not so clear and in many works is not well specified. This is probably related to the absence of a focus on this aspect in many works that are not reported by neurologists or neurophysiologists.

3.3. Differential Diagnosis of Acute Mononeuropathies and Related Examinations

Acute mononeuropathies are usually caused by compression (increased risk in cases of diabetes, hypothyroidism, weight loss or gain, alcoholism, acromegaly); all these pathologies should be considered. The evidence of neurophysiological and neuroimaging signs of nerve sufferance in a typical site of entrapment should suggest this diagnosis. There are, however, other pathologies that can cause isolated mononeuropathy, e.g., in some cases, the early manifestation of multineuropathy. Among these, there are systemic and non-systemic vasculitis, infectious diseases (leprosy, HIV), inflammatory diseases (sarcoidosis, MMN, CIDP variants) and toxic, metabolic (diabetes) and hereditary diseases (HNPP, hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy).

Peripheral nervous system impairment is frequent in most necrotizing vasculitis, with an ischemic–hypoxic mechanism due to arterial vessel occlusion secondary to vessel wall necrosis, mainly causing multineuropathies. This can occur both in primary forms (such as polyarteritis nodosa, Churg–Strauss syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis) and secondary forms (in the course of neoplasms, infectious diseases such as HCV, connective tissue diseases such as SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, scleroderma, rheumatic fever, amphetamines use) [

38,

39].

Infectious disease can cause direct nerve involvement, as in the case of leprosy [

40]. Leprosy neuropathy is the second most common neuropathy in the world (after diabetic neuropathy), and it is due to direct invasion of the skin and nerves by

M. leprae. Leprosy is endemic in tropical and subtropical regions; in other areas, it is suspected in people from or who have stayed in endemic areas. The diagnosis is confirmed by histological examination of the cutaneous lesions with evidence of acid-resistant bacteria.

Opportunistic CMV infection in HIV causes lumbosacral polyneuropathy but can also cause predominantly sensitive multineuropathy with pain and dysesthesia. Lyme disease can manifest as multineuropathy, mononeuropathy or brachial plexopathy, which can mimic brachial neuritis [

41].

Chronic hepatitis from HCV (and HBV) carries a risk of developing predominantly axonal sensory and sensorimotor poly- and multineuropathies usually associated with cryoglobulinemia (the presence of serum immunoglobulins which precipitate at low temperatures and solubilize at 37°) or autoimmune vasculitis [

42].

Other rare causes are possible. Sarcoidosis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory granulomatosis, which in 5–10% of cases can affect the nervous system and in 1% the peripheral nervous system [

43,

44]. Radiculopathies or mono-multineuropathies due to granulomatous infiltration, usually slowly progressive, may occur.

Multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) may present initially as mononeuropathy and is neurophysiologically characterized by the presence of conduction blocks [

45,

46].

In multiple myeloma, there may rarely be multineuropathy caused either by infiltration of malignant plasma cells or by interstitial deposition of paraprotein or light chains [

47,

48].

Diabetes is the most frequent cause of neuropathy, and the main risk factors are the duration of the disease and the blood sugar level [

49]. It can cause different clinical pictures. While the typical and more common symmetrical polyneuropathy has a predominantly toxic–metabolic etiology, the rarer mono-multineuropathic forms are due to vascular alterations in the vasa nervorum. The cranial nerves can be affected, particularly the third, but peripheral nerves of the limbs and trunk can also be impacted; in both cases, the genesis is ischemic.

Environmental and occupational exposure to lead, which is still widespread in developing countries, can cause axonal motor neuropathy, mainly of the radial nerve (with hand drop) but also of the tibialis anterior (foot drop).

Acute intermittent porphyria is the most common of the hepatic porphyrias. It is caused by a deficiency of the porphobilinogen synthetase enzyme and manifests as attacks of abdominal pain associated with fever, vomiting and leukocytosis. Sometimes there is neurological involvement with acute onset motor deficits and a multineuropathic distribution [

50].

Hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP), a rare autosomal dominant hereditary neuropathy caused by deletion of the PMP22 gene, is a polyneuropathy conferring an increased susceptibility to acute damage from the compression or entrapment of peripheral nerves. It manifests usually as acute transient peripheral paralysis with a mononeuropathic distribution that is not usually accompanied by strong pain. The nerve damage can regress spontaneously within a few days or weeks or persist for a long time.

NA can sometimes be hereditary (hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy). This autosomal dominant hereditary form of neuralgic amyotrophy is caused by mutations in the

SEPT9 gene, leading to recurrent episodes of typical brachial neuritis [

53,

54].

In order to make a correct diagnosis, a full anamnesis could be very helpful. Diabetes, a history of rheumatic diseases, staying in or coming from areas at risk for infectious pathologies and exposure to industrial toxicants could indicate diagnosis.

4. Best Treatment Approach for These Conditions

According to a Cochrane review, there are limited conservative treatment options in NA, and there is no evidence from randomized trials to support any particular form of treatment. In particular, some evidence suggests that early corticosteroid therapy may be effective against pain and lead to an earlier recovery, but there is no evidence of significant long-term improvement if compared with patients not treated with corticosteroids [

55].

There is no consensus on hourglass constriction treatment either. Conservative options include observation, resting and physical therapy to cope with muscle weakness, along with medications to control pain, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids, but there is no evidence of the effectiveness of these approaches. Some authors have suggested treating patients conservatively for 3 to 6 months, and afterward considering surgery if no improvements occur [

56,

57].

The type of surgical treatment implemented also varies in the literature. The most adopted is internal neurolysis, which allows a decompression of the internal components of the nerve promoting recovery [

59].

Resection of the affected segment with direct neurorrhaphy, or with the interposition of an autologous nerve graft, has also been reported. The use of more complex surgical techniques, such as tendon transfers, is sporadic [

60]. This technique should be limited to cases without any chance of spontaneous recovery, such as after failed neurosurgical treatment, or when severe chronic muscle atrophy and fibrotic substitution are observed (meaning at least after more than 1 year after the onset) [

61].

The prognosis is generally favorable after surgery, with a high rate of good motor recovery.

Surprisingly, overall, the surgical technique seemed to not influence the clinical outcome. This finding might simply signify that the chosen surgical treatment was appropriate for the nerve lesion, but still, the literature lacks the elements necessary to correlate the grade of nerve lesion to the best possible treatment, and both to the outcome. More data regarding the correlation between a common severity grading and the postoperative outcome are needed, as well as further parameters to predict the clinical outcome. The parameters that should be considered for this purpose could be the entity of constriction, the presence on the same nerve of more sites of constriction (as described in some cases) and the severity of nerve damage, assessed through neurophysiology.

In compressive neuropathies, prolonged compression may lead to demyelination and axonal loss, as well as nerve fascicle swelling, leading to epineural fibrosis. In these cases, which share similarities with cases of hourglass constriction, ultrasound-guided hydrodissection with different injectates (for example, normal saline, corticosteroids, local anesthetics, dextrose and platelet-rich plasma) has been demonstrated to provide not only a mechanical effect of releasing and decompressing the entrapped nerves but also a pharmacological effect relieving pain and promoting nerve healing through numerous mechanisms [

25,

37].

Since hourglass constriction and nerve torsion have a different treatment and prognosis than other cases of acute mononeuropathy/plexopathy without evidence of nerve constriction or torsion, it is of the uttermost importance to perform a correct diagnosis

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/brainsci14010067