The AT1 receptor has mainly been associated with the pathological effects of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) (e.g., hypertension, heart and kidney diseases), and constitutes a major therapeutic target. In contrast, the AT2 receptor is presented as the protective arm of this RAS, and its targeting via specific agonists is mainly used to counteract the effects of the AT1 receptor. The discovery of a local RAS has highlighted the importance of the balance between AT1/AT2 receptors at the tissue level. Disruption of this balance is suggested to be detrimental. The fine tuning of this balance is not limited to the regulation of the level of expression of these two receptors. Other mechanisms still largely unexplored, such as S-nitrosation of the AT1 receptor, homo- and heterodimerization, and the use of AT1 receptor-biased agonists, may significantly contribute to and/or interfere with the settings of this AT1/AT2 equilibrium.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, the team of Professor Jeffrey Atkinson, who recently passed away (1943–2023) and who taught Pharmacology at the Faculty of Pharmacy of Nancy for over 25 years, has contributed to demonstrating the major role of the renin angiotensin system (RAS) in the regulation of the cardiovascular system and the cerebral circulation [

1,

2,

3,

4].

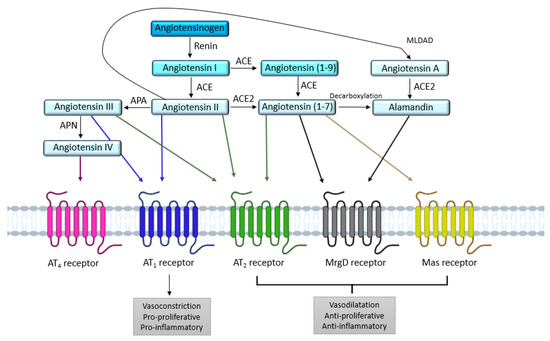

The RAS is an important hormonal system involved in numerous physiological processes, as shown by the copious literature devoted to the exploration and comprehension of this system since the discovery of renin in the late 19th century by Robert Tigerstedt [

5]. The systemic RAS is known for its involvement in vascular homeostasis, blood pressure regulation, and sodium and water retention in the kidney [

6]. Angiotensinogen, a glycoprotein produced by the liver and released in the blood is the first element of the systemic RAS. When blood pressure drops, the juxtaglomerular apparatus in the kidney releases renin, an enzyme which cleaves angiotensinogen into angiotensin I (Ang I), an inactive decapeptide. Subsequently, Ang I will be turned into angiotensin II (Ang II) by the angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) [

7], mainly expressed at the surface of endothelial cells. Ang II, an octapeptide, is the main endogenous ligand of the RAS, and binds to two main receptors: the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT

1) and the angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT

2), both belonging to the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family [

8,

9]. The hydrolysis of Ang II [

10] by the angiotensin II-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) produces the heptapeptide Ang-(1-7). Ang-(1-7) mediates signaling via the Mas receptor (MasR) and the Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor member D (MrgD receptor) (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the different receptors and enzymes involved in the renin angiotensin system. ACE: angiotensin I-converting enzyme; ACE2: angiotensin II-converting enzyme 2; APA: aminopeptidase A; APN: aminopeptidase N; AT1: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2: angiotensin II type 2 receptor; MLDAD: mononuclear leukocyte-derived aspartate decarboxylase; MrgD: Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor, member D.

The two main receptors for Ang II, the AT

1 and AT

2 receptors, share a similar affinity for Ang II [

9] but exert opposite actions [

19,

20]. These characteristics suggest that the stimulation of RAS and Ang II production may lead to physiological responses that directly reflect the functional balance between AT

1 and AT

2 receptors. From a systemic point of view, most of the known effects of RAS activation (elevated blood pressure, water and sodium retention, aldosterone release…) are subsequent to AT

1 receptor activation, as the expression and activity of AT

2 receptor seem too low to counteract AT

1 receptor stimulation. Apart from the systemic RAS, many studies have shown the existence of a localized expression of RAS components in various tissues. For instance, Campbell and Habener in 1986 measured angiotensinogen mRNA levels in 17 different organs in rats; brain, spinal cord, aorta, and mesentery levels were similar to hepatic levels, whereas the levels were lower in the kidney, adrenal, atria, lung, large intestine, spleen, and stomach [

21].

2. AT1 and AT2 Angiotensin II Receptors

2.1. AT1 Receptor

The AT

1 receptor is responsible for vasoconstriction, cell growth and proliferation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and also hypertrophy and hyperplasia [

24,

25]. Most of these actions result from the activation of intracellular signaling pathways involving several phospholipases and kinases (see below).

This receptor is expressed in several organs such as artery walls (smooth muscle cells), wherein it is highly expressed [

26], but also in the heart (cardiomyocytes) [

27], kidney (glomeruli, proximal convoluted tubules) [

28] and brain (neurons, microglia cells) [

29]. Two isoforms, the AT

1A and AT

1B receptors [

30], have been identified in rodents, showing a sequence homology of more than 96%, and identical functions. In humans, only one isoform has been identified.

The AT

1 receptor is a GPCR classically described to activate the phospholipase C (PLC) via G

q protein, although it also interacts with G

i, G

12/13, and G

s proteins [

20].

2.1.1. Structure

Advances in protein crystallization have led to the elucidation of crystalline structures for GPCRs, providing insight into activation and signaling mechanisms. As GPCRs are often involved in diseases, these crystalline structures also pave the way for structured drug design. The emergence of X-ray crystallography allowed the first crystalline structure of the AT

1 receptor to be co-crystallized with an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) [

31].

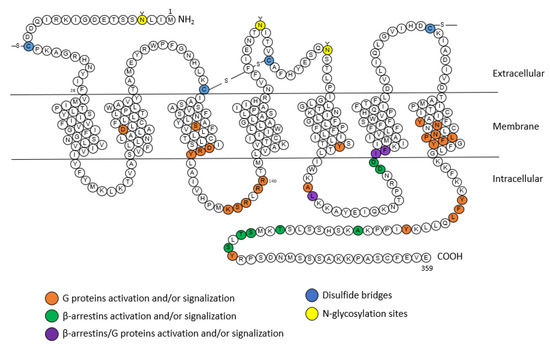

AT

1 receptor is a member of the seven transmembrane or GPCR family. Its sequence of 359 amino acids includes three

N-glycosylation sites (that enable the proper folding of the receptor and account for its trafficking to the membrane) and four cysteine residues at the extracellular regions [

20] (

Figure 2).

The AT

1 receptor can adopt three different conformations that directly influence its activity [

33]. The inactive conformation is stabilized by ARBs and does not lead to any downstream signaling. The “canonical active” conformation is observed after the binding of the endogenous ligand (Ang II), and allows the activation of many different signaling pathways (see below). The binding of Ang II results in a movement of the seventh transmembrane domain on the intracellular side, allowing the recruitment of G proteins or of β-arrestin. Finally, the “active alternative” conformation (incomplete movement of the seventh transmembrane domain on the intracellular side) prevents G protein coupling to the DRY motif of the receptor (

Figure 1), and only allows recruitment and stimulation of the β-arrestin signaling pathway [

33,

34].

Figure 2. Snake plot of the rat AT

1A receptor (modified from [

20,

35,

36]). Orange: amino acids for the activation of G proteins, green: amino acids for the activation of β-arrestins, purple: amino acids for the activation of G proteins and β-arrestins, blue: disulfide bridges, yellow: N-glycosylation sites. A: alanine; C: cysteine; D: aspartic acid; E: glutamic acid; F: phenylalanine; G: glycine; H: histidine; I: isoleucine; K: lysine; L: leucine; M: methionine; N: asparagine; P: proline; Q: glutamine; R: arginine; S: serine; T: threonine; V: valine; W: tryptophane; Y: tyrosine.

2.1.2. Signaling

G Protein Pathway

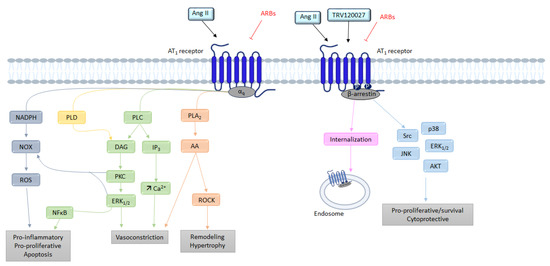

As evoked above, the AT1 receptor, once activated by Ang II, adopts the canonical active conformation, allowing its coupling to G proteins (Figure 3).

The activation of phospholipase C (PLC) is subsequent to Gα

q protein activation. This activation releases the α

q and β

γ subunits of the Gα

q protein. The α

q subunit activates the PLC, leading to the hydrolysis of phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-diphosphate (PIP

2) into inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP

3) and diacylglycerol (DAG) [

37]. The production of IP

3 induces a release of calcium (Ca

2+) from the endoplasmic reticulum, and then Ca

2+ complexes with calmodulin; this then activates myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK). Phosphorylation of myosin light chains (MLC) leads to muscle cell contraction and thus vasoconstriction.

AT

1 receptor stimulation also induces the activation of phospholipase A

2 (PLA

2) via the activation of the Gα

q protein. Once activated, PLA

2 allows the release of arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids [

41]. Arachidonic acid is then transformed into eicosanoids such as prostaglandins or thromboxane [

42] by cyclooxygenases or lipooxygenases. Several of these eicosanoids play a role in Ang II-induced contraction, whereas others (PGI2, PGE2) oppose it [

42]. The AT

1 receptor may also recruit other G proteins, such as the G

12/13 protein, involved in the activation of the RhoA/ROCK (Rho-associated protein kinase) signaling. These ROCKs are serine-threonine kinases with targets involved in the regulation of contractility [

43,

44].

β-Arrestins

After stimulation by Ang II, the AT

1 receptor is phosphorylated on its intracellular C-terminal serine and threonine residues by GPCR kinases (GRKs). This phosphorylation increases the affinity of β-arrestin-1 and β-arrestin-2 equally for the AT

1 receptor. The β-arrestins’ recruitment is known to inhibit G protein-induced signaling by interfering with the conformation of the receptor; it is also known to initiate, with the help of clathrins and AP-2 adaptor proteins, the internalization and sequestration of the AT

1 receptor coupled to its ligand, as well as the membrane recycling of the receptors [

34,

45].

Originally, arrestins were identified as central players in the desensitization and internalization of GPCRs. In addition to modulating GPCR signaling, in 1999, Robert Lefkowitz’s team showed that β-arrestins can also initiate a second wave of signaling [

46].

NADPH

Griendling et al. were the first to demonstrate the implication of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) in oxidative stress mediated by the AT

1 receptor [

49]. Using rat aortic VSMCs, they showed that treatment of VSMCs with Ang II for 4–6 h caused a nearly threefold increase in intracellular O

2- consumption. Ang II stimulates the activity of NAD(P)H oxidase (NOX), and thus generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

49].

NOX comprises five subunits, and in the absence of stimulation, some of its subunits are cytosolic, while others are membrane-bound [

50]. Ang II, via processes involving several players such as c-Src, PLD, PKC, PI3K, and transactivation of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), induces phosphorylation of the p47phox subunit, which causes the formation of a complex between cytosolic subunits, followed by transfer to the membrane, wherein the complex associates with membrane subunits to give the active form of the oxidase [

50]. This will lead to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as H

2O

2 or superoxide. These ROS are able to activate transcription factors such as activator protein-1 (AP-1) and nuclear factor kβ (NF-kβ), which will induce the expression of pro-inflammatory genes [

44].

Figure 3. Overview of the different signaling pathways following AT1 receptor activation. AA: arachidonic acid; Ang II: angiotensin II; ARBs: angiotensin receptor blockers; AT1: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2: angiotensin II type 2 receptor; Ca2+: calcium; DAG: diacylglycerol; ERK1/2: extracellular signal regulated kinase ½; IP3: inositol triphosphate; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; NFκB: nuclear factor kappa B; NOX: NADPH oxidase; PLA2: phospholipase A2; PLC: phospholipase C; PLD: phospholipase D; PKC: protein kinase; ROCK: Rho-associated protein kinase; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TRV120027: β-arrestin-biased AT1 agonists.

2.2. AT2 Receptor

The AT

2 receptor was initially not widely studied because of its low abundance in tissues making its study more difficult. However, it seems to play an important role in the development of the circulatory system, in particular by allowing the differentiation of precursor cells into smooth muscle cells during gestation, thus influencing the structure and function of blood vessels [

19]. After birth, AT

2 receptors are restricted to certain tissues such as those of the brain, heart, vascular endothelium, kidney, uterus, and ovary [

20]. Besides their decrease in locomotion and exploratory behavior associated with a decrease in spontaneous movements and rearing activity, AT

2 receptor-KO mice suffer from impaired drinking response to water deprivation [

51,

52]. Moreover, AT

2 receptor expression is upregulated during inflammation, and its stimulation reduces organ damage [

53].

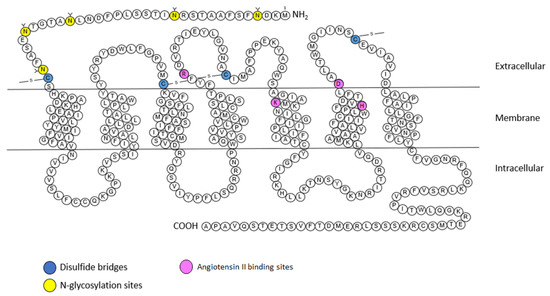

2.2.1. Structure

The first crystalline structures of the AT

2 receptor were published in 2017 [

54] demonstrating commonalities such as an extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) β-hairpin conformation.

The AT

2 receptor is composed of 363 amino acids and shares 34% homology with the AT

1 receptor. The AT

2 receptor has seven transmembrane domains, an extracellular amino terminus and an intracellular carboxy terminus (

Figure 4) [

9]. However the AT

2 receptor seems to have unique structural and functional differences, unlike other GPCRs (including AT

1 receptor), the AT

2 receptor is not internalized after stimulation by its endogenous agonist (Ang II) and this stimulation does not lead to the binding of stable GTP analogues [

20].

Figure 4. Snake plot of the rat AT

2 receptor (modified from [

57,

58,

59,

60]). Blue: disulfide bridges; yellow:

N-glycosylation sites. Purple: Angiotensin II binding sites. A: alanine; C: cysteine; D: aspartic acid; E: glutamic acid; F: phenylalanine; G: glycine; H: histidine; I: isoleucine; K: lysine; L: leucine; M: methionine; N: asparagine; P: proline; Q: glutamine; R: arginine; S: serine; T: threonine; V: valine; W: tryptophane; Y: tyrosine.

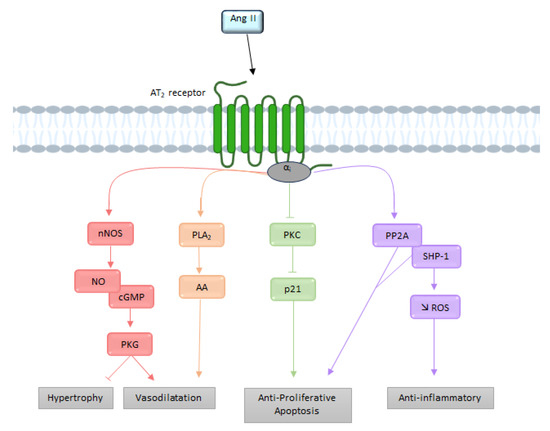

2.2.2. Signaling

The effects produced by stimulation of the AT

2 receptor are the result of the activation of intracellular signaling pathways different from those of the AT

1 receptor [

61]. It is interesting to note that unlike most other GPCRs, the AT

2 receptor does not associate with β-arrestins [

62]. Although the AT

2 receptor-induced signaling pathways are not yet well understood, they involve in particular the NO, the bradykinin (BK), and the activation of several proteins with tyrosine phosphatase activity [

63] (

Figure 5).

G Protein Pathway

Before being cloned and identified, this receptor was considered independent of any interaction with G proteins [

64]. Nevertheless, several biochemical and functional studies have indicated that the AT

2 receptor may recruit G

i [

19,

56], thereby resulting in activation of the NO-cyclic GMP (cGMP)-protein kinase G

i pathway [

65]. Subsequently cGMP activates PKG

i, which dephosphorylates myosin light chains via MLCK, thus preventing calcium from leaving the endoplasmic reticulum.

Moreover, G

i recruitment leads to downstream activation of various phosphatases, such as MAPks, SH2-domain-containing phosphatase 1 (SHP-1), and serine/threonine phosphatase 2A (PP2A), resulting in the opening of delayed rectifier K

+ channels and inhibition of T-type Ca

2+ channels [

40]. The activation of G

βγ subunits by the AT

2 receptor can induce the release of arachidonic acid via the PLA

2. The metabolites produced by arachidonic acid (prostaglandins or thromboxane) appear to contribute to AT

2 receptor-mediated vasodilation [

66].

Bradykinin

Siragy et al. has suggested that AT

2 receptor activity is mediated by stimulation of bradykinin (BK) production [

69]. This hypothesis was later confirmed by showing that AT

2 receptor inhibits the activity of Na

+/H

+ exchangers, resulting in acidification of the cell environment, which ultimately results in the release of BK [

70]. AT

2 receptor-dependent stimulation of BK receptors (B

2 receptor) seems to activate protein kinase A (PKA), which phosphorylates eNOS [

71].

Figure 5. Overview of the different signaling pathways following AT

2 receptor activation. AA: arachidonic acid; Ang II: angiotensin II; AT

2: angiotensin II type 2 receptor; cGMP: cyclic guanosine monophosphate; NO: nitric oxide; nNOS: neuronal nitric oxide synthase; PLA2: phospholipase A2; PKC: protein kinase; PP2A: serine/threonine phosphatase 2A; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SHP-1: SH2-domain-containing phosphatase 1.

3. The Functional AT1/AT2 Receptors Balance

3.1. Systemic Cardiovascular Impact

Most of the known physiological and pathological actions of Ang II are mediated by AT

1 receptors. One of the first systemic effects of the AT

1 receptor to be discovered was the regulation of blood pressure. A decrease in blood pressure will induce a decrease in renal perfusion, leading to a release of renin. The renin will then cleave angiotensinogen (in excess) into Ang I, which will in turn be cleaved into Ang II, which will cause vasoconstriction of the vessels, thereby increasing peripheral resistance with the effect of increasing blood pressure [

76]. In addition, Ang II can also increase blood pressure via a decrease in renal excretion of water and sodium [

6].

3.2. AT1/AT2 Balance in the Brain and Cerebral Circulation

3.2.1. Cerebral Circulation

The discovery of the presence of cerebral Ang II in 1971 revealed a cerebral RAS in dogs and rats [

78]. Subsequently, AT

1 and AT

2 receptors were localized in cerebral blood vessels in rats [

51], and then in the human brain [

79].

In a rat cranial window model, Vincent et al. showed that Ang II-induced vasoconstriction of cerebral arterioles was abolished when an AT

1 receptor antagonist was used, resulting in vasodilation, which was itself abolished when AT

2 receptor antagonists were used [

80]. In physiological conditions, the AT

1 receptor will allow vasoconstriction of cerebral arterioles while the AT

2 receptor has the opposite effect.

The AT

1 and AT

2 receptors and changes in the AT

1/AT

2 equilibrium are particularly important contributors to the regulation of cerebral circulation. Indeed, the vasoconstriction of cerebral arterioles observed during Ang II stimulation is the sum of AT

1 receptor-dependent vasoconstriction and AT

2 receptor-dependent vasodilation in physiological conditions.

3.2.2. Cardiovascular Regulation

The two receptors are expressed inside or near the medulla oblongata, the brain region which regulates cardiac rhythm and blood pressure. They are exclusively found in the neurons rather than the glia.

The localization of AT

1 receptors in the brain has been determined primarily by receptor autoradiography [

32,

85,

86]. These studies demonstrated a wide distribution of AT

1 receptors’ expression in the brain, including several regions involved in cardiovascular regulation. This distribution of AT

1 receptors in the brain was confirmed by the development of transgenic mice expressing the AT

1 receptor fused with eGFP [

87]. High densities of AT

1 receptors are found in the subfornical organ (SFO), the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), the area postrema (AP), the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), and the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) [

87]. AT

1 receptors are almost exclusively localized in neurons rather than in microglia, or astrocytes in these cardiovascular control centers [

88]. Furthermore, the AT

1 receptor appears to be predominantly expressed on glutamatergic neurons [

89].

3.2.3. Neuroinflammation

Inflammation is another example of the dysregulation of the AT

1/AT

2 receptors’ balance in the brain. Cells present in the brain such as astrocytes or microglial cells are the main sources of inflammation. In general, the activation of the AT

1 receptor in macrophages leads to the activation of the pro-inflammatory axis of the RAS, while activation of the AT

2 receptor promotes the activation of an anti-inflammatory axis [

94,

95].

In contrast, in pathological conditions such as inflammation, these receptors (and in particular, AT

1/NOX signaling) are upregulated. NOX-derived superoxides are amplified by the activation of NF-kβ and the RhoA/ROCK pathway, leading to the production of ROS. In addition, through a feedback mechanism, activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway enables increased expression of the AT

1 receptor via NF-kβ [

96].

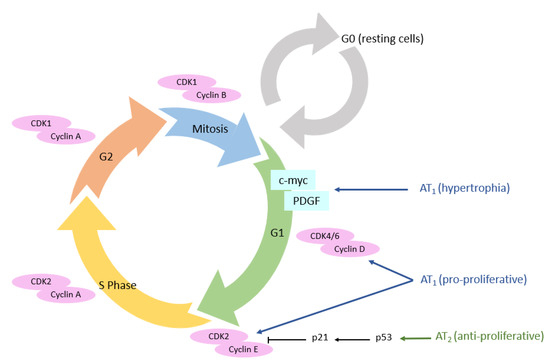

3.3. Cellular Cycle

The proliferation of normal cells is regulated by kinases called cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). The main actors in this cell cycle are cyclins, which regulate CDKs, enabling cells to progress through the cell cycle [

99]. AT

1 receptors promote cell proliferation pathways, in particular via the MAPK pathway, which allows the expression of cyclin and CDKs, itself allowing the advancement of cells in the cell cycle (

Figure 6) [

100].

Figure 6. AT1 and AT2 receptors’ expression and their impact on cell cycle. AT1 receptor: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2 receptor: angiotensin II type 2 receptor; CDK: cyclin-dependent kinases.

The AT

1 receptor directly induces cell hypertrophy, notably through the MAPk pathway, but also through the β-catenin pathway [

105,

106]. Cyclin D

1 will enable the transition from the G

0 to the G

1 phase of the cell cycle. The next expected step for cells in G

1, is the S phase, leading to cell proliferation.

In esophageal adenocarcinomal cells (EACs), Fujihara et al. showed that telmisartan induces antitumoral effects in EAC, both in vitro and in vivo. Following inhibition of the AT

1 receptor by telmisartan, cell cycle arrest in the G

0/G

1 phase is induced via the Akt/mTOR pathway in EAC cells [

110]. Similar results were obtained in breast cancer and cholangiocarcinoma cells [

111].

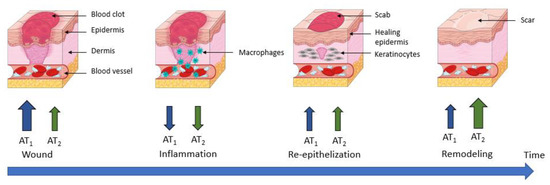

3.4. Wound Healing

Several studies reported dynamic changes in angiotensin receptor expression during the different phases of wound healing [

123,

124].

The expression of AT

1 and AT

2 receptors in the skin of young rats was first shown in 1992 by Viswanathan and Saavedra [

125]. AT

1 and AT

2 receptors are expressed in human fibroblasts, keratinocytes, and vascular endothelial cells. Both AT

1 and AT

2 receptors are found in myofibroblasts and keratinocytes in rodents [

126]. RAS components are present in the epidermal and dermal layers, but also in subcutaneous fat tissues, in microvessels, and in appendages such as hair follicles [

126,

127].

Regarding the functional role of the RAS in skin physiology, a recent study by Jiang et al. reported that Ang II promotes differentiation of keratinocytes from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMdSC) under physiological conditions [

129].

During wound healing, an organism will regulate the expression levels of AT

1 and AT

2 receptors, enabling a response to Ang II that is adapted to the situation. Immediately after wounding, an increase in both AT

1 and AT

2 receptor expression is observed, which seems slightly delayed and weaker for AT

2 receptors [

131]. In cultured keratinocytes, this regulation is detectable at the mRNA level 1 h after wounding, but the protein expression of AT

1 receptor peaks at 3 h, and that of AT

2 receptor peaks at 12 h after wounding [

126]. This specific early increase in AT

1 receptors could play a role in promoting blood clotting, initiating the inflammatory phase and inducing re-epithelialization by stimulating keratinocyte proliferation and migration [

132,

133].

In vivo, the wound healing process leads to an increase in receptor expression; this is higher for the AT1 receptor than for the AT2 receptor during the early phases of wound closure. Subsequently, there is a decrease in the expression of both receptors during the inflammation process, followed by an increase during re-epithelization.

Finally, during the last phase (remodeling), an increase in AT

1 and AT

2 receptors has been demonstrated, but this time with a dominance of the AT

2 receptor over the AT

1 receptor (

Figure 7) [

123,

133].

Figure 7. AT1 and AT2 receptors’ expression during wound healing. AT1 receptor: angiotensin II type 1 receptor; AT2 receptor: angiotensin II type 2 receptor.

This is consistent with what is known about both receptors, since in the early phases of wound healing and re-epithelization, a pro-proliferative action of AT

1 receptors is required to allow wound closure. Therefore, it has been shown that in mice KO for AT

1 receptors and rats treated with an AT

1 receptor antagonist, wound closure was delayed [

134,

135].

The formation of hypertrophic scars or keloids is a recurrent problem resulting from an insufficient control of proliferative and fibrotic processes in wound healing [

137]. Indeed, it has been shown that it is the overactivated cutaneous RAS that is involved in this process via the AT

1 receptor [

20,

138].

4. Mechanisms Regulating the AT1/AT2 Functional Balance

4.1. Functional Opposition vs. Expression Level

The response to Ang II results from the balance between the effects of each of these receptors.

This functional balance was confirmed in vivo using knockout mice for either the AT

1 receptor or AT

2 receptor. In AT

1A receptor KO mice, there was an absence of hypertensive response following Ang II injection, which is normally observed in wild-type mice. In addition, systemic blood pressure was markedly decreased in these mice [

141]. In the same AT

1A receptor KO mice and after treatment with an AT

1 receptor antagonist, a decrease in blood pressure was observed in mice pretreated with ACE, thus showing that AT

1B receptors also seem to play a role in the regulation of blood pressure.

The expression level of the receptors is also related to the mechanisms that regulate them. At the AT

1 receptor level, overexpression of ATRAP (AT

1 receptor-associated protein) inhibits AT

1 receptor-dependent PLC activation [

143], inositol phosphate production, and cell proliferation [

144], indicating that ATRAP acts as a negative regulator of AT

1 receptor signaling [

145].

The AT

2 receptor interacts with ATIP (AT

2 receptor interaction protein) [

149]. Decreased expression of this protein results in retention of the AT

2 receptor in cellular compartments, reducing their expression on the cell surface, and reducing AT

2 receptor-related effects. Expression of the AT

2 receptor at the membrane induces an increase in ATIP expression, creating a positive feedback loop [

149]. PARP-1 (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1) plays an important role in the regulation of AT

2 receptor expression.

4.2. Direct AT1/AT2 Receptors Interactions

4.2.1. AT1 Receptor Dimerization

Abdallah et al. showed that increased levels of AT

1 receptor homodimers were present on monocytes from patients with hypertension, which is an atherogenic risk factor, and that they were related to increased Ang II-dependent monocyte activity and adhesiveness [

153]. This increase leads to the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. In this study, in addition to showing that inhibition of Ang II release prevents the formation of AT

1 receptor homodimers, they observed that dimerized receptors increase G

q/11-mediated inositol phosphate signaling [

153].

The AT1 receptor and B2 receptor can form a heterodimeric complex. This heterodimerization between the AT1 receptor and B2 receptor in HEK-293 cells increased the efficacy and potency of Ang II, but decreased the potency and the efficacy of BK. To confirm this, the authors compared the Ang II- or BK-stimulated increase in inositol phosphates in HEK-293 cells expressing the indicated receptors.

4.2.2. AT2 Receptor Dimerization

AT

2 receptor homodimerization was first described by Miura et al. in PC12W cells and CHO cells transfected with AT

2R [

159]. They also showed that these AT

2 receptor homodimers allow constitutive signaling that leads to apoptosis. Furthermore, dimerization and pro-apoptotic signaling were not altered following AT

2 receptor stimulation, suggesting that this homodimerization is ligand-independent, which has also been reported in transfected HEK-293 cells [

160].

Like AT

1 receptors, AT

2 receptors can form heterodimers with B

2 receptors. AT

2 receptors mediate a vasodilatory cascade that includes BK, NO, and cGMP. Using a KO mouse model for B

2R, they showed that when AT

2 and B

2 receptors are simultaneously activated in vivo, NO and cGMP production increases [

162]. In a PC12W cell model, heterodimerization of these receptors was shown without any stimulation, suggesting the presence of constitutive heterodimers [

72].

The AT

2 receptors is also able to form a heterodimeric complex with MasR [

164]. This dimerization influences the RAS-protective Ang II/AT

2 axis, resulting in increased NO production and promoting diuretic–natriuretic response in obese Zucker rats [

164]. Several studies suggest that these receptors may be functionally interdependent; indeed, the AT

2 receptor antagonist (PD123319) reduced the vasodepressor effects of the MasR agonist Ang-(1-7) [

165]. Similarly, Ang-(1-7) mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation in the cerebral arteries [

166] and aortic rings of salt-fed animals [

167] was inhibited by PD123319 as well as the MasR antagonist (A-779).

Last but not least, AT

2/AT

1 heterodimerization was first described by AbdAlla et al. in PC-12 cells, rat fetal fibroblasts, and human myometrial tissue samples [

170]. They showed that AT

2/AT

1 dimerization was constitutive and led to inhibition of the AT

1 receptor-mediated G protein pathway. This inhibition of AT

1 receptor signaling does not require AT

2 receptor activation, as shown by the fact that AT

2/AT

1 heterodimerization is not affected by AT

2 receptor antagonists such as PD123319, and by the persistence of the effect in cells with dimers containing an AT

2 receptor mutant that is unable to bind agonists or to initiate AT

2 signaling.

Attenuation of AT

1 receptor signaling by the AT

2 receptor (via calcium signaling, ERK1/2 MAPK activation) as well as constitutive AT

2/AT

1 dimerization has been confirmed in studies by other groups in HeLa cells [

171] or HEK-293 transfected with AT

2/AT

1 [

172]. AT

2/AT

1 dimerization also appears to impact AT

2 intracellular trafficking, as AT

2/AT

1 dimers internalize upon Ang II stimulation (whereas AT

2 alone is unable to do so) [

171].

4.3. Post-Translational Modifications

4.3.1. N-Glycosylation

AT

1 receptor function is regulated by various post-translational modifications such as

N-glycosylation [

173]. To study the effects of

N-glycosylation on extracellular loops (ECL), artificial

N-glycosylation sequences were incorporated into ECL1, ECL2 and ECL3 [

174]. In ECL1,

N-glycosylation causes a very significant decrease in the ligand affinity and surface expression of the receptor; in ECL2, it leads to the synthesis of a misfolded receptor, and in ECL3

N-glycosylation produces mutant receptors with normal affinity and low surface expression. These results show that

N-glycosylation sites alter many properties of the AT

1 receptor, such as targeting, folding, affinity, and surface expression [

174].

4.3.2. Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation is another post-translational modification that can occur on the AT

1 receptor [

177]. Phosphorylation of AT

1 receptor serine/threonine residues is required for β-arrestin recruitment and receptor internalization [

178]. In contrast, in the kidneys and arteries, GRK4 has been shown to exacerbate urinary sodium retention and vasoconstriction by increasing AT

1 receptor expression [

179].

The AT

2 receptor is rapidly phosphorylated on a serine by PKC after activation by Ang II. The functional role of AT

2 receptor phosphorylation is not known. When triggered by AT

1 receptor activation, it appears to modulate the AT

2 receptor’s effects, as opposed to AT

1’s effects [

180].

4.3.3. S-Nitrosation

S-nitrosation is a mode of post-translational modification that allows the addition of a NO group to the sulfur atom of specific cysteine residues.

The AT

1 receptor contains ten cysteine residues. Four of these cysteines are involved in disulfide bridges at the extracellular loops, one is located on the cytoplasmic tail, and the other five are distributed in the transmembrane domains of the receptor. The affinity of the AT

1 receptor for Ang II is decreased in the presence of sodium nitroprusside (SNP), an NO donor. An assessment of the affinity of different mutated AT

1 receptors for each of five cysteines revealed the cysteine involved in sensitivity to sodium nitroprusside, cysteine residue 289 [

182].

The AT

2 receptor has 14 cysteine residues. It has seen that the four cysteines in the extracellular loops are engaged in disulfide bridges. The remaining ten cysteines are distributed on the transmembrane domains and the cytoplasmic tail.

5. Possible Ways to Tune the AT1/AT2 Functional Balance

5.1. Pushing the Balance Using Agonist/Antagonist Ligands

One of the most obvious means to act on the AT1/AT2 functional balance is to use agonists or antagonists towards one or the other receptor.

In order to rebalance the AT1/AT2 balance, the use of specific molecules targeting the receptors seems to be an interesting avenue. Indeed, this would make it possible to block or activate one specific receptor, which cannot be achieved with ACE inhibitors, for example, as they prevent both receptors’ activation by inhibiting Ang I cleavage.

AT

1 receptor antagonists were the first molecules discovered in this sense. In the case of pathologies associated with AT

1 receptor, the ideal is to be able to abolish the overexpression of the receptor responsible for the imbalance in order to orient it in favor of the AT

2 receptor. AT

1 receptor antagonists are widely used to treat hypertension as well as cardiac diseases (heart failure or myocardial infarction). In vitro and in vivo, losartan is a reversible competitive AT

1 receptor antagonist that inhibits the Ang II-induced vasoconstriction of blood [

184]. However, complete blockade of the receptor then amounts to promoting activation of the AT

2 receptor, which will tip the balance in the other direction instead of bringing it back to equilibrium.

Another method would be to act on the AT

2 receptor itself by using an agonist of the latter. For this, molecules capable of specifically activating the receptor have been developed, such as CGP42112A, which is a peptide, or C21, which is a synthetic compound. A study on the effects of CGP42112A in the same SHR model was performed, and the authors tested CGP42112A in the presence or absence of candesartan. The results showed that the use of candesartan alone at a high concentration lowered blood pressure in SHR rats, and that CGP42112A only provided a depressant effect in the presence of candesartan [

185].

5.2. Selective Activation of the β-Arrestin Pathway

The use of biased agonists is another strategy to regulate the AT

1/AT

2 receptors’ balance. A biased agonist is a receptor-specific ligand capable of selectively activating a single signaling pathway by preferentially stabilizing one of the receptor conformations. This phenomenon is also called “functional selectivity”. In the case of the AT

1 receptor, several biased agonists have been developed that allow AT

1 receptor to adopt an alternative active conformation [

45]. For example SII, TRV120027, and TRV120023 selectively activate the β-arrestin pathway while inhibiting the G protein pathway [

197].

SII is a modified Ang II peptide, which can trigger the phosphorylation of the AT

1 receptor, and thus β-arrestin recruitment [

203]. SII elicits GRK6 and β-arrestin 2-dependent ERK activation, and promotes β-arrestin-regulated Akt activity and mTOR phosphorylation to stimulate protein synthesis [

204]. TRV120023 has been reported to only recruit β-arrestin while blocking G protein activation, enhancing myocyte contractility but without promoting hypertrophy, as seen with Ang II [

205].

TRV120027 has been studied in several preclinical studies in a heart failure model, and has shown promising results [

206]. A recent study just demonstrated that β-arrestin signaling, mediated by the PAR-1 receptor, produces prolonged activation of MAPK 42/44, which increases PDGF-β secretion. It has been shown that after ischemic stroke, PDGF-β secretion can provide increased protection of endothelial function and barrier integrity [

207]. Similarly, there are biased agonists that selectively activate the G protein pathway, such as TRV120055 or TRV120056 [

33].

6. Conclusions

In summary, the AT1/AT2 balance is very important from a physiological point of view, and that the disturbance of this balance leads to the appearance of pathologies, most often as a result of the dominance of the AT1 receptor over the AT2 receptor. However, emerging studies have shown that secondary signaling of β-arrestins could have beneficial effects. This is why a finer regulation of this balance via S-nitrosation of the receptors or the use of biased agonists seems to be interesting, and could open new therapeutic perspectives.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules28145481