Photodetectors are important photoelectric devices that realize sensing detection through photoelectric signal transformation and have been widely used in flame sensing, conversion communication, environmental monitoring, video imaging, night vision imaging, military tracking, medical detection, and other fields. Ultraviolet with a wavelength less than 280 nm is defined as a deep ultraviolet band that will be absorbed by ozone in the atmosphere before entering the earth. Almost no signal background exists in this band on the earth, which is also called a solar-blind band. The application fields represented by ultraviolet short-range secure communication, shipborne guidance, ozone layer monitoring, and water pollution treatment need the continuous development, maturity, transformation, and application of deep ultraviolet (DUV) detection technology. Therefore, further research and development of DUV detection technology have attracted the extensive attention of researchers in relevant fields, whether in daily life or in the construction of modern national defense.

- aluminum nitride

- photodetectors

- nanowires

- semiconductor

- deep ultraviolet

1. Introduction

2. AlN Nanostructures

3. AlN Thin Films

4. AlN Heterostructures

| Device Structure | Fabrication Method | Light of Detection/nm | Dark Current | On/Off Ratio | Rejection Ratio | Specific Detectivity/Jones | EQE | Responsivity | Rise Time/ Decay Time |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlN nanowire photoconductor |

CVD | 325 | 20 | 2.7 × 106 A/W @40 V |

~1 ms | [12] | ||||

| AlN nanowire photoconductor |

LPCVD | 254 | 7.7 s/ 11.5 s |

[14] | ||||||

| AlN micro/nanowire MSM |

PVT | 190 | <100 fA@20 V | VUV/UV-C ~104 |

254 | 0.39 A/W @50 V |

<0.1 s/ <0.2 s |

[15] | ||

| AlN nanowire MSM |

LPCVD | 254 | 2.43 mA/W @15 V |

0.27 s/ 0.41 s |

[16] | |||||

| AlN nanowire Schottky |

LPCVD | 254 | 2.32 × 1012 | 584 | 1187.5 mA/W@30 V | [17] | ||||

| AlN film 3D-MSM |

MOCVD | 200 | 2.6 pA | 1.51 mA/W @0 V |

[32] | |||||

| AlN film 3D-MSM |

MOCVD | 200 | 4.2 pA@8 V | 8 mA/W@2 V | 2.61 ns/ 3 ns |

[33] | ||||

| AlN film FC-3DMSM |

MOCVD | 200 | 5.96 pA@8 V | 9.6 mA/W @2 V |

2.90 ns/ 2.92 ns |

[33] | ||||

| AlN film MSM |

PVD | 200 | 14.6 pA@5 V | 7835@−2 V | 0.6 mA/W @5 V |

0.9 s/ 1.8 s |

[34] | |||

| AlN/AlGaN Heterostructures MSM |

MOCVD | 240 | 10 pA@20 V | [36] | ||||||

| AlN/AlGaN HeterostructuresTFT | LP-MOCVD | 240 | 1.7 pA@20 V | >108 | 240/280 >102 |

1.5 × 1018 @20 V |

1.6 × 105 A/W @20 V |

537.5 ps 3.1 us |

[37] | |

| Ga2O3/AlN heterojunction p-n |

sputter | 253 | 0.145 pA | 2.14 × 104 | 5.98 × 1010 | 95.95 μA/W @0 V |

90 ms/ 116 ms |

[38] | ||

| Gr/AlN/GaN Heterostructures p-i-n |

MOCVD | 194 | 194/212 >103 |

16 | 25 mA/W @0 V |

[39] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cryst13060915

References

- Xie, C.; Lu, X.; Tong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, F.; Liang, L.; Luo, L.; Wu, Y. Recent Progress in Solar-Blind Deep-Ultraviolet Photodetectors Based on Inorganic Ultrawide Bandgap Semiconductors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806006.

- Shang, H.; Dai, M.; Gao, F.; Yang, H.; Hu, P.; Jia, D.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H. Progress in Inorganic Ultraviolet Photoelectric Materials. Mater. China 2019, 38, 875–886.

- Feng, W.; Jin, Z.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, J.; Jia, S.; Dong, L.; Yoon, J.; Zhou, L.; Vajtai, R.; Tour, J.M.; et al. A fast and zero-biased photodetector based on GaTe-InSe vertical 2D p-n heterojunction. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 025008.

- Dai, M.; Chen, H.; Feng, R.; Feng, W.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, C.-Y.; et al. A Dual-Band Multilayer InSe Self-Powered Photodetector with High Performance Induced by Surface Plasmon Resonance and Asymmetric Schottky Junction. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8739–8747.

- Zou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gu, H. Ultraviolet Detectors Based on Wide Bandgap Semiconductor Nanowire: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2072.

- Feng, W.; Zheng, W.; Cao, W.; Hu, P. Back Gated Multilayer InSe Transistors with Enhanced Carrier Mobilities via the Suppression of Carrier Scattering from a Dielectric Interface. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 6587–6593.

- Lu, Y.-J.; Lin, C.-N.; Shan, C.-X. Optoelectronic Diamond: Growth, Properties, and Photodetection Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800359.

- Briegleb, F.; Geuther, A. Ueber das Stickstoffmagnesium und die Affinitäten des Stickgases zu Metallen. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1862, 123, 228–241.

- Taylor, K.M.; Lenie, C. Some Properties of Aluminum Nitride. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1960, 107, 308.

- Cox, G.; Cummins, D.; Kawabe, K.; Tredgold, R. On the preparation, optical properties and electrical behaviour of aluminium nitride. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1967, 28, 543–548.

- Alaie, Z.; Nejad, S.M.; Yousefi, M. Recent advances in ultraviolet photodetectors. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 29, 16–55.

- Liu, F.; Li, L.; Guo, T.; Gan, H.; Mo, X.; Chen, J.; Deng, S.; Xu, N. Investigation on the photoconductive behaviors of an individual AlN nanowire under different excited lights. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2012, 7, 454.

- Kenry; Yong, K.T.; Yu, S.F. AlN nanowires: Synthesis, physical properties, and nanoelectronics applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 5341–5360.

- Teker, K. Dielectrophoretic Assembly of Aluminum Nitride (AlN) Single Nanowire Deep Ultraviolet Photodetector. J. Nano Res. 2019, 60, 86–93.

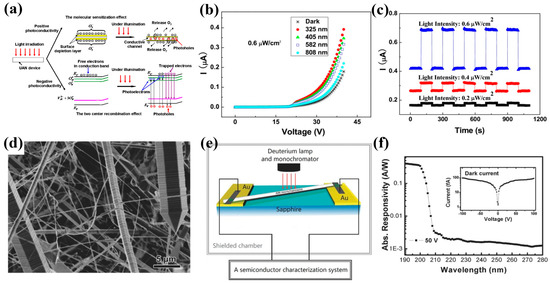

- Zheng, W.; Huang, F.; Zheng, R.; Wu, H. Low-Dimensional Structure Vacuum-Ultraviolet-Sensitive (λ < 200 nm) Photodetector with Fast-Response Speed Based on High-Quality AlN Micro/Nanowire. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3921–3927.

- Ali, Y.A.; Teker, K. Fabrication of ultraviolet photodetector with aluminum nitride nanowire networks via direct transfer method. Microelectron. Eng. 2019, 211, 26–28.

- Ozdemir, Y.B.; Teker, K.; Yildirim, M.A. High-responsivity flexible ultraviolet photodetector via single aluminum nitride nanowire. Opt. Eng. 2021, 60, 057104.

- Hartmann, C.; Wollweber, J.; Dittmar, A.; Irmscher, K.; Kwasniewski, A.; Langhans, F.; Neugut, T.; Bickermann, M. Preparation of Bulk AlN Seeds by Spontaneous Nucleation of Freestanding Crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 52, 08JA06.

- Wang, Q.; Lei, D.; He, G.; Gong, J.; Huang, J.; Wu, J. Characterization of 60 mm AlN Single Crystal Wafers Grown by the Physical Vapor Transport Method. Phys. Status Solidi 2019, 216, 1900118.

- Hu, W.; Guo, L.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W. Growing AlN crystals on SiC seeds: Effects of growth temperature and seed orientation. J. Cryst. Growth 2020, 541, 125654.

- Knauer, A.; Mogilatenko, A.; Hagedorn, S.; Enslin, J.; Wernicke, T.; Kneissl, M.; Weyers, M. Correlation of sapphire off-cut and reduction of defect density in MOVPE grown AlN. Phys. Status Solidi 2016, 253, 809–813.

- Claudel, A.; Blanquet, E.; Chaussende, D.; Audier, M.; Pique, D.; Pons, M. Thermodynamic and experimental investigations on the growth of thick aluminum nitride layers by high temperature CVD. J. Cryst. Growth 2009, 311, 3371–3379.

- Kumagai, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Nagashima, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Dalmau, R.; Schlesser, R.; Moody, B.; Xie, J.; Murakami, H.; Koukitu, A.; et al. Preparation of a Freestanding AlN Substrate from a Thick AlN Layer Grown by Hydride Vapor Phase Epitaxy on a Bulk AlN Substrate Prepared by Physical Vapor Transport. Appl. Phys. Express 2012, 5, 055504.

- Mansurov, V.; Nikitin, A.; Galitsyn, Y.; Svitasheva, S.; Zhuravlev, K.; Osvath, Z.; Dobos, L.; Horvath, Z.; Pecz, B. AlN growth on sapphire substrate by ammonia MBE. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 300, 145–150.

- Shukla, G.; Khare, A. Dependence of N2 pressure on the crystal structure and surface quality of AlN thin films deposited via pulsed laser deposition technique at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 2057–2062.

- Szekeres, A.; Fogarassy, Z.; Petrik, P.; Vlaikova, E.; Cziraki, A.; Socol, G.; Ristoscu, C.; Grigorescu, S.; Mihailescu, I. Structural characterization of AlN films synthesized by pulsed laser deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 5370–5374.

- Li, T.; Han, J.; Xing, Y.; Deng, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Shi, F.; Yu, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Influence of pressure on the properties of AlN deposited by DC reactive magnetron sputtering on Si (100) substrate. Micro Nano Lett. 2019, 14, 146–149.

- Xiao, S.; Suzuki, R.; Miyake, H.; Harada, S.; Ujihara, T. Improvement mechanism of sputtered AlN films by high-temperature annealing. J. Cryst. Growth 2018, 502, 41–44.

- Chen, M.-R.; Chen, H.-G.; Kao, H.-L.; Wu, M.-G.; Tzou, A.-J.; Chen, J.S.; Chou, H. Structural and optical properties of low temperature grown AlN films on sapphire using helicon sputtering system. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2015, 33, 031503.

- Murtaza, S.H.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, M. Investigation of AlN/Si based heterogeneous Junction using inter-digitated electrodes for enhanced UV light detection. Optik 2022, 265, 169534.

- Yang, R.Y.; Hsiung, C.M.; Chen, H.H.; Wu, H.W.; Shih, M.C. Effect of AlN film thickness on photo/dark currents of MSM UV photodetector. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2008, 50, 2863–2866.

- Li, T.; Song, W.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L. Self-powered asymmetric metal–semiconductor–metal AlN deep ultraviolet detector. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 637–640.

- Li, T.; Long, L.; Hu, Z.; Wan, R.; Gong, X.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; et al. Three-dimensional metal–semiconductor–metal AlN deep-ultraviolet detector. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 3325–3328.

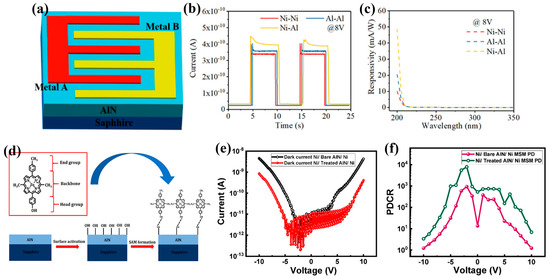

- Kaushik, S.; Naik, T.R.; Alka, A.; Garg, M.; Tak, B.R.; Ravikanth, M.; Rao, V.R.; Singh, R. Surface Modification of AlN Using Organic Molecular Layer for Improved Deep UV Photodetector Performance. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 739–746.

- Eller, B.S.; Yang, J.; Nemanich, R.J. Electronic surface and dielectric interface states on GaN and AlGaN. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2013, 31, 050807.

- Averin, S.V.; Kuznetsov, P.I.; Zhitov, V.A.; Alkeev, N.V.; Kotov, V.M.; Dorofeev, A.A.; Gladysheva, N.B. AlN/AlGaN heterostructures for selective ultraviolet MSM detectors. Tech. Phys. 2011, 56, 295–297.

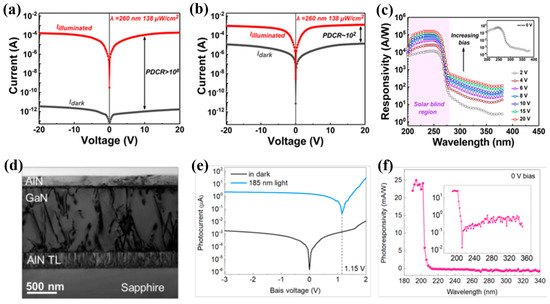

- Lu, J.; Lv, Z.; Qiu, X.; Lai, S.; Jiang, H. Ultrasensitive and high-speed AlGaN/AlN solar-blind ultraviolet photodetector: A full-channel-self-depleted phototransistor by a virtual photogate. Photon Res. 2022, 10, 2229.

- Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; An, Y. A Ga2O3/AlN heterojunction for self-powered solar-blind photodetection with high photo-to-dark current ratio and fast response speed. Phys. Scr. 2021, 96, 125835.

- Li, T.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Z. Heteroepitaxy Growth and Characterization of High-Quality AlN Films for Far-Ultraviolet Photodetection. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4169.