Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections worldwide, occurring in both community and healthcare settings. Although the clinical symptoms of UTIs are heterogeneous and range from uncomplicated (uUTIs) to complicated (cUTIs), most UTIs are usually treated empirically. Bacteria are the main causative agents of these infections, although more rarely, other microorganisms, such as fungi and some viruses, have been reported to be responsible for UTIs.

- uropathogens

- virulence factors

- pathogenesis

- antibiotic resistance

1. Introduction

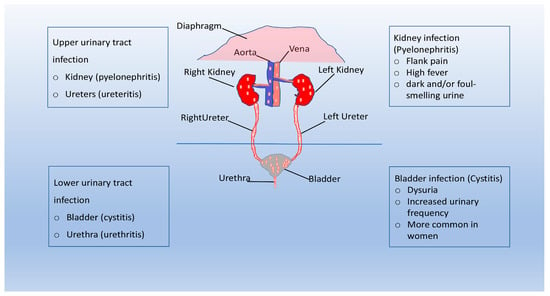

The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra, and its main function is to filter blood by removing waste products and excess water. The urinary system plays a key role in removing the waste products of metabolism from the bloodstream. Other important functions performed by the system are the normalization of the concentration of ions and solutes in the blood and the regulation of blood volume and blood pressure [1]. In healthy people, urine is sterile or contains very few microorganisms that can cause an infection [2]. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are infections that can occur in the urethra (urethritis), bladder (cystitis), or kidneys (pyelonephritis) and are one of the world’s most common infectious diseases, affecting 150 million people each year, with significant morbidity and high medical costs (e.g., it has been estimated that the economic burden of recurrent UTIs in the United States is more than $5 billion each year) [3,4]. Although symptomatology varies depending on the location of these infections, UTIs have a negative impact on patients’ relationships, both intimate and social, resulting in a decreased quality of life [5,6]. UTIs are classified as either uncomplicated (uUTIs) or complicated (cUTIs) [7]. uUTIs typically affect healthy patients in the absence of structural or neurological abnormalities of the urinary tract [4]. cUTIs are defined as complicated when they are associated with urinary tract abnormalities that increase susceptibility to infection, such as catheterization or functional or anatomical abnormalities (e.g., obstructive uropathy, urinary retention, neurogenic bladder, renal failure, pregnancy, and the presence of calculi) [4,8].

In both community and hospital settings, the Enterobacteriaceae family is predominant in UTIs, and the main isolated pathogen is uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) [9,10]. The latter is also the most common causative agent of cUTI [10]. Antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are more prevalent in hospitals than in community samples (e.g., carbapenemase-resistant Enterobacteriaceae) [11]. UTIs are mainly caused by bacteria, while the involvement of other microorganisms, such as fungi and viruses, is quite rare. Candida albicans is the most common type of fungus that causes UTIs. Common causes of viral UTI are cytomegalovirus, type 1 human Polyomavirus, and herpes simplex virus [12,13].

2. Pathogenesis of UTI

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) begin when gut-resident uropathogens colonize the urethra and subsequently the bladder through the action of specific adhesins. If the host’s inflammatory response fails to eliminate all bacteria, they begin to multiply, producing toxins and enzymes that promote their survival. Subsequent colonization of the kidneys can evolve into bacteremia if the pathogen crosses the kidney epithelial barrier (Figure 1). In complicated UTIs, infection by uropathogens is followed by bladder compromise, which occurs with catheterization. A very common situation is the accumulation of fibrinogen on the catheter as a result of the strong immune response induced by catheterization. Uropathogens, through the expression of fibrinogen-binding proteins, bind to the catheter. Bacteria also multiply as a result of biofilm protection, and if the infection is left untreated, it can progress to pyelonephritis and bacteremia (Figure 1). UTIs are the most common bacterial infection in humans worldwide and the most common hospital-acquired infection [14,15]. The spread of UTIs is closely linked to the effectiveness of a number of strategies that uropathogens have developed to adhere to and invade host tissues [16,17]. Often, the infection does not seem particularly severe, especially in the early stages, but it can worsen significantly in the presence of complicating factors [18,19]. Complicating factors that are involved in the progression of UTI are biofilms, urinary stasis due to obstruction, and catheters. UTIs comprise a heterogeneous group of clinical disorders that vary in terms of the etiology and severity of conditions. The risk of UTI is influenced by a wide range of intrinsic and acquired factors, such as urinary retention, vesicoureteral reflux, frequent sexual intercourse, prostate gland enlargement, vulvovaginal atrophy, and family history. The use of spermicides may also increase the risk of UTI in women [19,20]. A urine culture with ≥105 colony-forming units/mL without any specific UTI symptoms is defined asymptomatic bacteriuria, as it usually resolves spontaneously and does not require treatment [21]. Asymptomatic UTIs should be treated only in selected cases, such as pregnant women, neutropenic patients, and those undergoing genitourinary surgery, as antibiotic treatment may contribute to the development of bacterial resistance [22,23]. In contrast, symptomatic UTIs are commonly treated with antibiotics that can alter the intestinal and vaginal microbiota, increasing the risk factors for the spread of multidrug-resistant microorganisms [4,23,24].

Figure 1. Pathogenesis of UTI. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) start when uropathogens colonize the urethra and subsequently the bladder through the action of specific adhesins. If the bacteria are able to evade the immune system, they begin to multiply and biofilms form. Bacteria can reach the kidney from the lower urinary tract, and UTI can evolve into bacteremia. In complicated UTI, uropathogens are usually able to bind to the catheter and multiply due to the protection of the biofilm. If left untreated, the infection can progress to pyelonephritis and bacteraemia.

3. Classification of UTI

In general, UTIs are named according to the site of infection: urethritis is inflammation of the urethra, ureteritis refers to inflammation of the ureter, and cystitis and pyelonephritis involve the bladder and kidney, respectively [25]. UTIs are further classified according to the presence of predisposing conditions for infection (uncomplicated or complicated) or the nature of the event (primary or recurrent) [25,26,27]. In most cases, uUTIs are caused by uropathogens that reside in the intestine and, after accidental contamination of the urethra, migrate, colonizing the bladder [28]. While sharing the same dynamics described for uncomplicated infections, cUTIs occur in the presence of predisposing factors, such as functional or structural abnormalities of the urinary tract [29]. Other typical features of complicated UTIs include a significantly higher rate of treatment failure and systemic or invasive tissue involvement [22,28]. Three or more uncomplicated UTIs within 12 months or two or more infections within six months define recurrent UTIs; usually, recurrences in this type of infection are due to the same microorganism responsible for the previous infections [30,31].

4. Immune Response to Uropathogens

Although the urinary tract is often exposed to microorganisms from the gastrointestinal tract, infection by these microorganisms is a rather rare occurrence due to the innate immune defenses of the urinary tract [32]. Previous studies have shown that the immune response is carefully regulated so as not to compromise the structural integrity of the epithelial barrier. Macrophages and mast cells play a key role in immune regulation of the urinary tract, coordinating the recruitment and initiation of neutrophil responses that lead to the removal of bacteria in the bladder. In addition, these cells are critical in preventing an excessive neutrophil response from causing damage to bladder tissue and predisposing this organ to persistent infection [33].

5. Virulence Factors of the Main Uropathogens

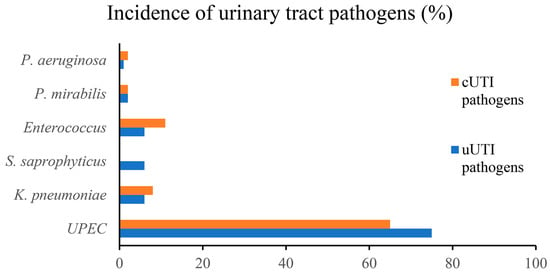

The ability of different uropathogens to successfully adhere to and colonize the epithelium of the lower urinary tract is related to their ability to express specific virulence factors [34]. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is the most common causative agent of both uUTIs and cUTIs [34]. Most UTIs are caused by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria residing in the colon, such as Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae [4,34]. Other causative agents include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Group B Streptococcus (GBS), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [4]. Figure 2 shows the epidemiology of different uropathogens in uUTIs and cUTIs. On the cell surface of uropathogens are several adhesion proteins that play a crucial role in the initial interactions between the host and pathogen [34]. In addition, adhesins have recently been found to promote both the attachment of bacteria and invasion of host tissues in the urinary tract. Among the best-known adhesion factors are the pili of uropathogenic bacteria belonging to both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Two distinct pathways are required for pili assembly in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, known as the chaperone/usher pathway and the sortase-assembled pili pathway, respectively [34]. These uropathogens use different types of adhesins that promote binding and biofilm formation on biotic and abiotic surfaces. In this context, it is important to note that most UTIs are biofilm-associated infections in which uropathogens colonize both the mucosa of the urinary tract and indwelling devices such as urinary catheters [35]. Biofilm formation by these pathogenic bacteria requires specific virulence factors that play a key role in inducing adhesion to host epithelial cells or catheter materials [35,36]. Bacterial biofilms play an important role in UTIs, being responsible for the persistence of infections that result in recurrence and relapse. Since eradication of biofilms often cannot be achieved by antibiotic treatment, new approaches for eradication of aggressive biofilms are being tested, such as phagotherapy, enzymatic degradation, antimicrobic peptides, and nanoparticles [37]. Table 1 shows the main types of adhesins that are crucial for biofilm formation. These structures promote the attachment of uropathogens to biotic/abiotic surfaces. Uropathogens are also producers of toxins, proteases (e.g., elastase and phospho-lipase) and iron-harvesting siderophores, all of which are involved in the onset and spread of UTIs [38].

Figure 2. Epidemiology of uropathogens in uUTIs and cUTIs.

Table 1. Main types of adhesins expressed by Gram-negative and Gram-positive uropathogens.

| Uropathogens | Adhesin | Biotic/Abiotic Surface | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (UPEC) | Type 1 fimbriae Type 2, P fimbriae Dr adhesion S fimbriae F1C |

binds to kidney cells and promotes the formation of a biofilm binds to Globosides, a sub-class of the lipid class glycosphingolipid. binds bladder and kidney epithelial cells binds to receptors containing sialic acid binds to glycolipid receptors present in the endothelial cells of bladder and kidney and promotes biofilm formation |

[39] [40] [41] [42] [43] |

| K. pneumoniae | Type 1 fimbriae Type 3 fimbriae |

Binds to the mannose-binding receptors and promote biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces promote biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces |

[44] [44] |

| P. aeruginosa | T4Pa | Binds to glycosphingolipid receptors present in host epithelial cells and promotes biofilm formation. | [34] |

| P. mirabilis | MRP fimbriae | binds mannosylated glycoproteins of bladder cells | [45] |

| NAF fimbriae Mrp/H |

binds with glycolipids promote the formation of biofilms in the urinary tract |

[45,46] | |

| S. saprophyticus | Aas adhesin SdrI adhesin Uaf adhesin |

binds to human ureters binds to collagens binds to bladder epithelial cells |

[34] |

| E. faecalis | Enterococcal Surface Protein | promote primary attachment and biofilm formation on biotic and abiotic surface | [47] |

UPEC: UroPathogenic Escherichia coli; F1C, type 1-like immunological group C pili; T4Pa, type IV pili; MRP, mannose-resistant Proteus fimbriae; NAF, Non-agglutinating fimbriae; Aas, autolysin/adhesin of Staphylococcus saprophyticus; SdrI, serine-aspartate repeat proteins; Uaf, Uro-adherence factor.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pathogens12040623

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!