Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) virulence relies on its ability to manipulate host macrophages, where it establishes intracellular niches to cross mucosal barriers and avoid pathogen destruction. First, Mtb subverts the endocytic pathway, preventing phagolysosome fusion and proteolytic digestion. Second, it activates innate immune responses to induce its transmigration into the lung parenchyma. There, infected macrophages attract more permissive cells, expanding intracellular niches. Mtb induces the adaptive responses that stimulate its containment and encourage a long life inside granulomas. Finally, the pathogen induces necrotic cell death in macrophages, granuloma destruction, and lung cavitation for transmission. Common to all these events is the major virulence factor: the “early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa” (ESAT-6, also called EsxA).

The loss or gain of mycobacterial virulence is closely linked to the ability of mycobacteria to produce and secrete ESAT-6, and the extension of virulence is correlated with the amount of protein secreted. ESAT-6 secretion from the bacilli requires both the expression of the esx-1 locus for the type VII secretion apparatus and the transcription of both the ESAT-6 gene (esxA) and the culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) gene (esx-B) contained in the RD1 region of the genome. In addition, it requires the protein EspA, which is not encoded in the esx-1 locus but in the extended espACD operon adjacent to RD8.

All species and strains deleted in the esx-1 locus, the internal RD1 region, or the esx-1 extended locus espACD exhibit an attenuated phenotype. Mutants with deletions on ESX-1 of Mtb are attenuated in virulence, translating into reduced survival of mycobacteria in cultured macrophages or in experimental animal models of TB. Curiously, the saprophyte species M. smegmatis (Ms) also encodes for an ESX-1 apparatus; however, it does not appear to confer Ms virulence capabilities, as demonstrated by its inability to survive in human macrophages or in amoeba in the environment. Predatory amoeba may have contributed to the evolutionary pressure that selected mycobacterial pathogens for intracellular survival.

1. Introduction

Human tuberculosis (TB) is one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases [

1,

2,

3]. In 2022, the WHO reported approximately 1.6 million deaths, 10 million new infections, and an estimated one-quarter of the human population being latently infected [

3]. Infection control is hampered by the limited efficacy of a 100-year-old Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine and the emergence of multidrug-resistant strains against 70-year-old antibiotics, particularly those used in first-line therapy [

3]. There is also a need to develop better diagnostic tools that are more sensitive, use simple instruments, are easy to handle in remote geographical areas, and are cost-effective for the rapid detection of Mtb. Moreover, although new methods are being implemented [

4], the currently available methods do not allow differentiation between the different stages of infection [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is considered the main causative agent of human TB [

9]. Mtb infections primarily affect the lungs, a condition that contributes to high transmissibility by the respiratory route [

9]. Although not transmitted from person-to-person, extrapulmonary TB is a second form of disease manifestation that particularly affects less immunocompetent individuals, namely, children or people who are co-infected with HIV [

10,

11,

12]. In addition to Mtb, other pathogens can also infect humans and cause TB with similar clinical symptoms [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These include

M. africanum, which is restricted to humans in West Africa [

21,

22,

23], where it causes nearly half of all pulmonary TB [

18,

19,

20], and the animal-adapted species

M. bovis, which is estimated to cause TB in about 2% of the world’s population [

24,

25].

M.caprae is responsible for a smaller burden of zoonotic TB [

26]. They all belong to the

Mycobacterium tuberculosis species complex (MTBC), which also includes the more distant

M. canettii group and additional species that cause TB in animals such as

M. microti [

27],

M. pinnipedii,

M. orygis, and

M. mungi [

20,

23,

28,

29,

30]. Although each of these animal MTBC variants causes TB in its host species, they may trigger slight or no disease outside of their adapted host, especially in immunocompetent hosts [

13,

30,

31]. However, conditions such as the geographic prevalence of infected animals, close human contact, the route of transmission (milk, infected meat, or airborne droplets containing pathogens), and conditions such as HIV infection or other immunosuppressive conditions should be taken into account to assess the true threat to public health [

32].

The animal-adapted species are more recent pathogens that emerged as crowd-associated diseases during the Neolithic demographic expansion along with the development of animal domestication [

33]. Mtb ascended long before the establishment of crowded populations 70 thousand years ago and accompanied the exodus of Homo sapiens from Africa during the Neolithic expansion [

34]. The initial virulence of Mtb is therefore strongly adapted to the occasional availability of the population to be infected and to an evolutionary ability to survive for a long time in the host until the opportunity for transmission arises. Consequently, Mtb infections have evolved in low human population densities, exhibiting a pattern of chronic development, accompanied by decades of latency before progressing to active disease [

10,

11,

12]. It is a well-adapted human pathogen, requiring the induction of a strong inflammation and destruction of lung tissue for transmission and evolutionary survival [

9,

34,

35]. This feature is unusual in most pathogens, where virulence is not associated with their spread to other hosts [

36].

The pathogen does not seem to require virulence factors such as the usual pili, toxins, or capsules that are essential for the invasion of epithelial barriers [

9]. Nevertheless, their potential involvement should not be ignored, as a capsule and pili have recently been identified in Mtb, although their roles during infection in vivo are still unclear [

37,

38,

39]. Mtb virulence relies on its ability to manipulate host macrophages, where it establishes intracellular niches to cross mucosal barriers and avoid pathogen destruction. First, Mtb subverts the endocytic pathway, preventing phagolysosome fusion and proteolytic digestion [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Second, it activates innate immune responses to induce its transmigration into the lung parenchyma [

46,

47]. There, infected macrophages attract more permissive cells, expanding intracellular niches [

9,

48,

49,

50]. Mtb induces the adaptive responses that stimulate its containment and encourage a long life inside granulomas [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Finally, the pathogen induces necrotic cell death in macrophages, granuloma destruction, and lung cavitation for transmission [

47,

49,

55,

56]. Common to all these events is the major virulence factor: the “early secreted antigenic target of 6 kDa” (ESAT-6, also called EsxA).

2. Virulence Evolution among MTBC

A comparative genomic analysis among MTBC species reveals more than 99.95% sequence homology [

57], but they differ mainly by large sequence polymorphisms [

18] relative to Mtb, reflected by the so-called regions of difference (RD) and translated into deletions [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61] or punctual insertional sequences [

62]. These observations reinforce the ancestral origin of Mtb, reflecting a loss of genes during the transmission to animals that enabled a fitness gain in the new host and a loss of robustness in humans. In the case of

M. africanum, lineage 5 (L5) is more associated with Mtb-like lineages, while lineages L6 and 9 display an RD that is more associated with

M. bovis-like animal-adapted species [

19,

20].

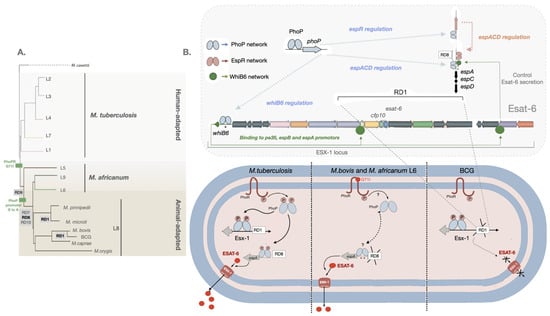

Important cumulative findings from these studies have identified more pathogenic MTBC disease-causing species from less fit ones with deletions/insertions/mutations in the RD regions affecting the PhoPR two-component virulence system or the genes under the control of this signal transduction regulator [

63,

64]. This includes the regions called the region of difference 1 (RD1) and the region of difference 8 (RD8), which are responsible for the production and secretion of the virulence factor ESAT-6 [

29,

62].

Particularly, the RD1 region is deleted in the animal-adapted species

M. microtii and was first described in BCG, where it is absent and associated with the attenuation of this live vaccine during its propagation in vitro [

23,

65,

66]. The RD8 deletion is associated with animal-adapted species, and it affects the regulatory PhoPR-dependent region of the

espACD operon involved in ESAT-6 secretion (

Figure 1). The genetic transfer of mutations affecting the PhoP binding region in

M. bovis and in the closely related

M. africanum L6 into the Mtb

sensu stricto human species resulted in reduced ESAT-6 secretion and lower virulence [

29]. Remarkably, the deleterious effects of these mutations were partially compensated by RD8 deletions in both species, allowing ESAT-6 secretion to some extent by creating alternative regulatory sequences [

62]. The observed attenuated ESAT-6 responses contribute to the observed slower clinical progression from infection to disease when compared to Mtb [

18,

67]. Conversely, the insertion of the IS

6110 element upstream of the PhoP binding locus resulted in the upregulation of the operon in one multidrug-resistant

M. bovis strain, responsible for an unusually high human transmissibility and partially reversing the

phoPR-bovis-associated fitness loss [

68,

69].

Figure 1. Control of ESAT-6 secretion by PhoP-dependent regulatory networks. (

A) Lineages of the MTBC with RD deletions and PhoPR mutations are highlighted [

20,

23,

28,

29]. (

B) Several genes from the ESX-1 and the extended ESX-1 (

espACD and

espR) regions required for ESAT-6 protein synthesis and exports are displayed. PhoP (blue ellipses) is a transcriptional activator and an effector of the signal transducer PhoR that interacts with the

espR,

espA, and

whiB6 promoters. In its phosphorylated form, PhoP binds to DNA with higher affinity. Mtb, carrying a functional PhoR, is able to sense a stress-like stimulus and subsequently phosphorylate PhoP. EspR (pink ellipses) activates the

espACD locus. WhiB6 (green circles) also interacts with the promoter regions of the

espA,

pe35, and

espB genes. The

espACD locus is activated by all these circuits, and the protein translated EspA is required for ESAT-6 secretion. The RD1, absent in BCG, and RD8, absent in

M. africanum L6 and L8 animal-adapted lineages (including

M. bovis), as well as polymorphisms in the

espACD and

whiB6 promoters (asterisks), are indicated.

M. bovis and

M. africanum L6, carrying a defective PhoR G71I allele, are expected to generate a low-affinity binding effector due to phosphorylation impairment of PhoP. Nevertheless, ESAT-6 secretion in these species is restored to some extent by compensatory mutations in the

espACD promoter region, including RD8 deletions and species-specific polymorphisms (asterisks) [

62].

The ESAT-6 gene (

esxA) is part of the

esx-1 locus, a group of genes encoding the type VII secretion system that allows the secretion of the virulence factor ESAT-6 from the pathogen, known as the ESAT-6 secretion system 1 (ESX-1) [

70,

71] (

Figure 1).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom13060968